Essays

Making Stories Visible

A Yemeni Art History

I.

In March 2012, a month after former president of Yemen Ali Abdallah Saleh[1] formally left power following a year of contentious mobilizations demanding his overthrow, the walls of Sana'a became covered in colourful murals and sprayed with myriad paintings. Located on walls that were bullet-marked by violent clashes between demonstrators and forces loyal to the regime during the period before Saleh's departure, the first paintings to appear were all dated and signed. They were attributed to Murad Subay, the painter in his 20s who initiated this artistic action.[2] Up until he decided to place a call on his Facebook page to take over the streets with brushes and sprays, he had worked on his canvases – which he recreated from March 2012 onwards on Sana'a's walls – without exhibiting his work at any of the art spaces that existed in the city.[3] Through this initiative, he triggered an artistic action characterized by the use of public space not only to paint, but also to reflect on issues of political concern through art, involving a participative audience.

The campaigns Murad Subay initiated became Yemen's largest art exhibition ever undertaken in public space. In Sana'a, kilometres of walls were intervened by a diverse public made up of an eclectic youth mostly under 30 and 40, formed by painters, activists, writers and all sorts of passers-by including, at times, even the military stationed at nearby crossroads. Other cities of the country followed suit, and in places like Taez, the walls showed reproductions of works by Hashem Ali (1945–2009), one of the pioneering figures of Yemeni modern painting.[4] In a country without museums specifically dedicated to modern and contemporary art, street art became a medium to portray pioneering works side by side with those of the youngest generation of painters and photographers. Street art was, for the first time, making it possible for art to reach unknown numbers – an unspecified audience, or public, who not only watched the walls as they were being transformed, but participated in that very change. In all, the interventions in public space portrayed mixed aesthetics, combined artistic expression with social and political commentary, and brought to the street snapshots, sequences of Yemeni art history.

The art campaigns initiated by Subay have radically and symbolically changed public space in urban centres of Yemen, namely Sana'a, turning the walls into memorial sites of struggle and public paintings into political awareness devices, making them, at times, reflect and refract collective action.[5] By referring to this now, my aim is to point out the dynamics affecting Yemeni art worlds[6] so as to explore how arts infrastructures were developed and used in Yemen before artistic practices took over street walls. Certainly, if young painters in their 20s find in public space and – more specifically – the walls of the streets, possible canvases where they are able to reproduce old and new works, then it is certain that prevalent models of exhibition, valourization, and recognition are being questioned as relatively obsolete.

However, it is important to note that street art is not the central focus of this essay. The case of Subay's campaigns serves to point out ongoing questions about the dynamics of Yemen's art infrastructures. I have written elsewhere about these street art campaigns, explaining more about how and when these practices emerged and how they differ from Arab and European street art, not to mention the ways they are similar (mainly during 2011) to Egyptian, Libyan or Bahraini street art.[7]

Indeed, street art has become rather visible in the international media, which has equally contributed to obscure the clearly different dynamics at play in the Yemeni case. Thus, in what follows, I will focus on describing the larger context from which these street art campaigns emerged. By contextualizing the emergence of artistic practices, my aim is to provide a rough cartography of arts infrastructures in Yemen.[8]

II.

Although historicizing artistic practices in Yemen is limited here by space and scope, it is possible to highlight certain elements pertinent to providing a general image of Yemeni art history. In order to do so, it should be stressed that painting is certainly the most visible and recognized of all disciplines. Practised in the southern city of Aden since the 1930s and 1940s during the British occupation (1839–1967), and later developed in the northern cities of Taez and Sana'a[9] during the late 1960s and mainly the 1970s, painting has since occupied a central place in Yemeni visual arts. Today, sculpture and photography, though also pursued, remain relatively marginal in relation to painting, as also do installation and video art.

Since the first 'clubs' (in Arabic nadi) of the 1930s and 1940s in Aden to the artistic associations of the 1950s, and to the establishment of the first spaces dedicated to formalized learning, exhibition and commercialization of art in the late 1970s, very different initiatives structured the domain of the arts in Yemen such as workshops, institutes, artist studios, galleries and art departments at university and at non art-related museums (i.e: military museums). Most but not all of these initiatives participated in a process through which the arts were institutionalized – that is, regulated by the state. With different levels of intensity, the state established, intervened and incorporated art infrastructures at changing levels throughout the years. In this light, the state strongly mediated the art scene between the 1970s and until the 1990 unification, provoking a rich period of political art with trained painters producing posters for political parties or large canvases portraying political figures. From unification onwards and until 2002, followed a period marked by the retreat of the state from the artistic domain. A new phase of strong state intervention continued from 2002 until 2007, again followed by a new retreat. Intermittently, the state has played an important role in the establishment of institutions as well as in the education and professionalization of artists. As I illustrate in what follows, the fluctuating character of this intervention was equally marked by the emergence of independent and non-governmental initiatives, suggesting efforts being made towards a relatively more autonomous art scene.

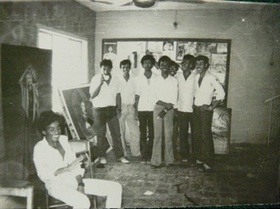

This complex process started in the 1970s, linking the emergence of spaces where painting could be practised in a more independent manner, like in artist studios, to more or less formalized learning, like the state-run 'free workshops'.[10] One example of the first type was the studio opened by Hashem Ali, which did not lead to any type of formal diploma but informally educated painters since the early 1970s.

The second type dates back to 1976 and was located in Aden. Known as the 'Free workshop' (al marsam al hurr), it was an initiative of the Ministry of Culture and Education of the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen that became the first space that provided a diploma after three years of study. It started with a group of 30 to 40 Yemeni students taught by the Egyptian artist Abdul Aziz Darwish, whom like many other foreigners was employed by the state within an effort to expand education. Organized as an evening workshop, it lasted until 1978, when art classes where also being taught at the state-run Jamil Ghanem Institute of Fine Arts by Egyptian, Palestinian, Iraqi and Russian teachers artists.

During the 1980s the artistic movement located in Aden grew and expanded, in part through the establishment of professional associations for artists. For instance, the Association of Young Plastic [artists] (jama'ia al tashkilin al shabab) included, at that time, 80 members whose works were exhibited in Yemen and outside the country. Also during this decade, a few independent commercial galleries like Gallery N°1, Colours, and Al Ameen Gallery, opened in Sana'a and Aden after the initiative of painters. They reflected on the need to commercialize art works while also signifying an expansion in the art scene in terms of adding independent spaces to the arts infrastructures.

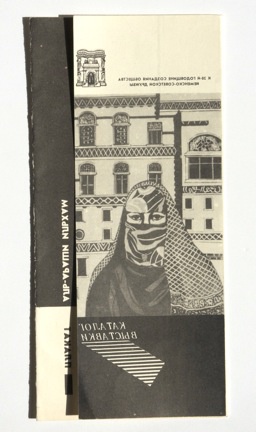

It was also during these years that the largest group of Yemeni students to have studied abroad left the country to pursue Fine Arts-related degrees in the former Soviet Union.[11] Between the 1970s and the 1990s, state scholarships were provided to pursue such studies, both in former North and South Yemen, and students returned to Yemen after having earned qualifications ranging from Bachelor's to Doctor of Philosophy degrees. The return of these students to Yemen around the time of the unification (1990) nourished a dynamic of nationalization affecting the domain of visual arts. Yemenis took over teaching jobs in Aden, Sana'a and later on, in the coastal city of Hodeidah.[12] Trained artists also worked in the art department of the military and national museums established during the 1960s in Aden and Taez and the 1980s in Sana'a,[13] which before and after unification made use of painting for political purposes.

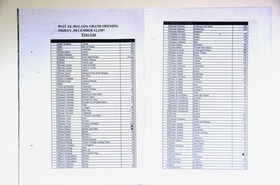

Throughout the 1990s, 'groups' formed with large numbers of participants, generally more than ten and up to 40. These groups announced a feature in a period marked by a search, through collective efforts that were more or less independent from governmental resources, for better conditions that might alleviate reduced opportunities to exhibit and commercialize art works. Certain examples include the Group of Modern Art (jama'a al fann al hadith, 1990s) and the Cultural Circle al-Halaqa (jama'a al halaqa, 1996–2001). Other individual and collective initiatives emerged, taking the form of informal workshops to teach painting, such as the opening of Mohammed al-Yamani's studio in Sana'a (1997–) and the establishment of non-governmental art spaces that combined exhibitions with art-related events and publications. Such was the case of Bayt al-Halaqa (1997–2001), an art space found by Dutch expatriates living in Sana'a, which was simultaneously a space for workshops and exhibitions linked to the group 'Cultural Circle al-Halaqa' with artists based in Sana'a, Aden and Taez, and a cultural publication, The Halaqa Journal (last issued in 2001). These types of initiatives reflected both, the diversification of spaces dedicated to visual arts as well as the search for independent networks, all triggered by a period marked by the retreat of the state.

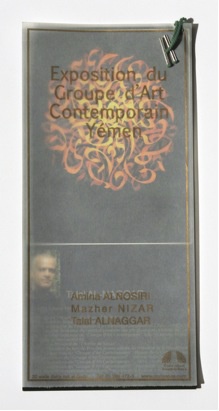

In the 2000s, another type of group of artists emerged. Among the main features these new groups introduced, they differed from the groups of the 1990s by their reduced membership (usually less than six), which contrasted also with the large memberships characteristic of associations, syndicates and federations that previously grouped artists. Some of them also differed from previous groups, in the fact that they were female-only groups like Halat Lawnia from Hodeidah (2005–) and a group yet without a name based in Aden (2010–). Some of these groups were also linked to the establishment of art spaces dedicated not only to exhibit and possibly sell their works, but also to entertain debates through the organization of weekly meetings, as was the case with Group of Contemporary Art, which established Atelier, an artist-run space located in the old city of Sana'a (2001–2009). These initiatives were a variation from similar ones attempted in the 1980s in the fact that they not only served to commercialize art works, like galleries do, but they reflected the need to tackle different purposes, like promote debate among artists and their public, create networks, showcase works, and propose informal learning to artists without a formal training in fine arts.

During the 2000s, these groups of artists participated in the expansion of artistic networks, reflecting independent efforts that notwithstanding aim to better integrate and attain institutionally run spaces and opportunities. Such are the cases of the only-female groups from Hodeidah and Aden above mentioned, but also mixed ones like the Sanaani Group of Contemporary Art or only-male groups such as jama'a ruh al-fann (Art's Spirit Group, 2005–2007) based in Aden.

From 2002 to 2007, another phase of institutionalization took place, this time through mainly fostering the establishment of art spaces dedicated to the exhibition and commercialization of art. Relatively decentralizing the artistic movement, which had until then been centred in the capital Sana'a, the Ministry of Culture established Houses of Art in different governorates[14] where permanent exhibitions and training workshops were organized, and where art works could be bought. Such efforts were successful at incorporating some of the young and emerging artists (below their 30s during these years) to state-run institutions and networks (i.e. newly opened Houses of Art and exhibitions organized at the Houses of Culture). From 2008 onwards, the Ministry of Culture launched yearly international forums for plastic arts, which together with a state-run gallery opened in 2011 demonstrated an interest for the internationalization and commercialization of Yemeni art. These efforts apart, certain artists still describe the years that followed and led to the 2011 mobilizations and until 2014 by an again fluctuating retreat of the state. This perception is possibly due to the saturation of the state-run networks with always the same artists. Consequently, opportunities for independent experiences were again triggered and favoured by the experimental environment of revolutionary times. For instance, non-governmental multi-disciplinary spaces such as 'The basement' and the 'Gallery Rauffa Hassan' opened respectively in 2011 and 2013, mixing exhibitions with music concerts or poetry performances. Such spaces attracted young artists, among which those not included or not participant to state-run networks found different possibilities for visibility and recognition. It is during this relatively more independent and experimental phase that Murad Subay took over the streets to put his paintings on the walls and outside the market and the state-run spaces.

III.

As is evident in the case of the street art campaigns undertaken by Murad Subay, the period that followed the contentious mobilizations that spread throughout the country in 2011 have also affected the domain of visual arts. In the same way that the mobilizations unleashed political creativity, they also created a safe environment where different kinds of social experiments could be tried. Subay's street art campaigns are one of such experiments.

As I have briefly explained, arts infrastructures have developed in Yemen not only through a process defined and directed by the state. Individual and collective non-governmental initiatives have also structured Yemeni art worlds. Nevertheless, both these realms were disrupted with Subay's campaigns. This is because, although organized independently from governmental infrastructures, independent initiatives have seldom aimed at proposing an alternative to institutional artistic networks. In other words, art spaces or groups created with a will to obtain more autonomy from the state have rarely been established in order to counter governmental initiatives. On the contrary, they have produced ways to better compete, integrate and participate in those institutional networks of exhibitions, commercialization, and in general, opportunities of visibility and recognition.

What Murad Subay's campaigns introduced was a sort of break from these dynamics: by placing art expression on the street and by provoking participation from artists but not limited to them, he has disrupted modes of exhibition-making, not to mention art's interaction with audiences. Most importantly, he has placed art works outside the market. These ruptures from the ways in which art has been displayed and recognized until 2011, has introduced a type of art that is extremely public, given the work is being shown on the streets and is thus accessible by anyone, free of any entry fee, and thus open to anyone. Audiences have turned into possible participants, and streets into open museums and galleries.

Given how different art initiatives such as multidisciplinary exhibition spaces and installations on the streets have been undertaken by different actors after 2011 and mostly also in their 20s, Subay's campaigns have been successful at attaining a visibility unprecedented for any art initiative taking place in Yemen. Inscribing this painter's campaign into a historicized context allows the opportunity to think about what kind of histories – understood both as narratives and as historical accounts – are put forward in a global context, where artistic practices of peripheral countries such as Yemen unfortunately remain invisible.

[1] He formally retained power since 1978, when he became president of the former Yemen Arab Republic (YAR). Upon the unification of 1990, he became president of the current Republic of Yemen (ROY) until 2012.

[2] Murad Subay developed three collective campaigns (in Arabic s. hamla, pl. hamlat) in Sana'a between March 2012 and May 2014: 'Colour the walls of your street', 'The walls remember their faces', and '12 hours'. Besides these campaigns, he has also wheat-pasted photographs realized by one of his brothers. Refer to Murad Subay's blog for short documentaries, articles, interviews and photographs of these campaigns: http://www.muradsubay.wordpress.com.

[3] There are several spaces dedicated to visual arts in the capital, Sana'a, both state-run and independent. Among the state-run: the House of Culture hosts temporary exhibitions while permanent ones can be viewed at the House of Art where paintings can also be bought; the National Museum in collaboration with European cultural institutions has hosted a number of art exhibitions and installations, and the Sana'a Gallery located whithin the main building of the Ministry of Culture besides exhibiting also comercializes art works. Within the framework of cultural cooperation, European cultural centres also organize temporary exhibitions. Some of the independent initiatives that opened in the last five years include Kawn Foundation, the Basement, Gallery Rauffa Hassan and Reemart Gallery.

[4] Called 'Colours of life', this artistic action took started possibly in May or July 2012 in Taez. For a brief explanation and images refer to http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UR2qx14GO0Y&feature=youtu.be and http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/contents/articles/galleries/yemen-graffiti-vandalism-or-high-art.html. In Taez, certain images were vandalized with black painting.

[5] Mainly in a chapter under publication and presented at the symposium 'The Revolutionary Public Sphere: Aesthetics, Poetics & Politics', organized by the Project for Advanced Research in Global Communication (PARGC) at the Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, April 2014. For shorter analysis refer to my chapter 'Les murs prennent la parole. Street art révolutionnaire au Yémen,' in Jeunesses arabes: Loisirs, cultures et politique, Laurent Bonnefoy and Myriam Catusse, dir., (Paris: La Découverte, 2013); 'Mobiliser et sensibiliser à travers le street art au Yémen,' in 34 Short Stories, (Paris: Bétonsalon-Centre d'art et de recherche et les Editions de Beaux-Arts de Paris, forthcoming in 2014); and 'From Street Politics to Street Art in Yemen,' Nafas website, July 2013 http://universes-in-universe.org/eng/nafas/articles/2013/street_art_yemen.

[6] Contrary to an individualistic conception of the artist and the art works, sociologist Howard S. Becker proposes a collective approach: 'art worlds consist of all the people whose activities are necessary to the production of the characteristic works which that world, and perhaps others as well, define as art [...] We can think of an art world as an established network of cooperative links among participants [...] Works of art, from this point of view, are not the products of individual makers, "artists" who possess a rare and special gift. They are, rather, joint products of all the people who cooperate via an art world's characteristic conventions to bring works like that into existence'. H. S. Becker, Art Worlds (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982 and 2008), 34-35.

[7] Mainly in a chapter under publication and presented at the symposium 'The Revolutionary Public Sphere: Aesthetics, Poetics & Politics,' organized by the Project for Advanced Research in Global Communication (PARGC) at the Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, April 2014. For shorter analysis refer to my chapter: Ibid., 'Les murs prennent la parole. Street art révolutionnaire au Yémen' and 'From Street Politics to Street Art in Yemen'.

[8] I conducted my doctoral research in Yemen from May 2008 until March 2011.

[9] Until the unification of 1990, Yemen was divided into two separate states. The Yemen Arab Republic, in the northern part of the country, was established in 1962 and marked the end of the Zaydi Imamate, which also coincided between 1839-1918 with the Ottoman occupation. The south, divided in 25 sultanates and sheykhas that during 128 years were grouped into two protectorates, was occupied by the British until 1967. Until unification, the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen represented the only Arab regime of the region explicitly Marxist.

[10] Translated as 'the Free Atelier' or 'the Open Studio', such workshops also emerged during the 1960s in other parts of the Arabian Peninsula, for instance in Kuwait or Qatar, and were also state-run initiatives. On Kuwait see for instance: Fatima al Qadiri and Kaelen Wilson-Goldie, 'Farida Al Sultan,' Bidoun (2010): 42-45. The catalogue Swalif. Qatari art between memory and modernity published by the Mathaf museum in 2011 also mentions them on the glossary on page 24.

[11] For a detailed analysis of this group, refer to my article 'Impact of transnational experiences: the case of Yemeni artists in the Soviet Union,' Chroniques Yéménites 17 (2013).

[12] The University of Hodeidah, located in the Red Sea coast, is the only public university in the entire country to offer the possibility to study visual arts since the late 1990s.

[13] Museums from the former South were looted during the short war of 1994 (5 May to 7 July), where the armies of the former nothern and southern states confronted each other. For a study of museums in Yemen refer to Gregoire Nicolet's master thesis: Les musées du Yémen. Développement et enjeux de l'institution (Geneva: Universités de Genève et de Lausanne, 2007).

[14] Sanaa, Dhamar, Ibb, Yarîm, Hodeidah and Aden among them.