Essays

Scripts of the Art World

Did a new kind of art emerge after Gezi? It could be argued that the political discourses and styles in the sphere of art in Istanbul had foreshadowed Gezi before it had begun, given how the art world here generally exists outside of the prevalent political discourses and norms in Turkey. Indeed, artists shared much with the Gezi mindset: humouristic, against the use of violence, a-nationalist, and inclusive of LGBT communities and other minorities – and from the first days of the Gezi Park protest, artists were there as citizens. After Gezi, artists returned to whatever it was they were doing before the occupation started, their work continuing to engage with the questions and emerging ideas of the zeitgeist, including the motto, 'the personal is political'. Indeed, the notion that society can transform from the bottom up is alive and kicking; it is the core of many activist, participatory and socially engaged art practices today.

But an art genie keeps raising the question in my mind: is it really so? This has been pestering me lately. I don't see Gezi as a presently historicized event that began and ended on a certain date. Just like its counterparts – the waves of uprisings throughout the world in recent years – Gezi emerged in an unexpected manner. It was not part of a rational script that could be turned into a narrative. There is no one answer to such questions around where the movement came from, why it happened, and if it faded out, how it faded out. These questions can be answered only ex-, post-, and inadequately. Gezi was not expected and it happened, just like Tahrir, the Occupy movements, and so on. And this intense experience, which cannot readily be conveyed, continues in the veins of the society in the form of minute or large-scale activations.

I think, as opposed to a society that sobered up after the intense days of Gezi Park, an ebbing of spirit took place in the art world, from where Gezi drew part of its energy and in so doing, satisfied it. Now, the art world is relieved but also in a state of loss. As it is pondering what it should do, it is developing an ethical and political discourse that is problematizing sponsorship relations in art as its central issue and demanding that institutions and galleries recognize artists' rights. I consider the latter as one of the after effects of Gezi. Artists are also more sober, and they are demanding more transparency and rights. This is an attitude that displays parallels to the activist attitude, which demands from the Justice and Development Party – the AKP, the ruling party in Turkey since 2002 – that the state becomes more transparent, and the dealings it has with corporations, foundations, and banks are exposed.

Of course, it should also be said that this demand for transparency is actually a call for a confession. Everyone knows what has to become transparent; the data and chain of relations are evident. What is being demanded is that these relations – amongst foundations, institutions, corporations and state – are exposed, put on trial, and the necessary measures are taken.

It is possible to see reflections of this political language and form in the recent history of contemporary art as well. Cases that are well known are Joseph Beuys entering the European Parliament – as if it were a logical outcome of his artistic stance-as an MP of the Green Party; Wolfgang Zinggl of the Austrian Wochenklausur group being elected as an MP in Austria once again from the Green Party; artists organizing in New York in the 1970s under the name of 'Art Workers' Coalition' to demand transparency and equality in representation from institutions, and W.A.G.E. demanding artists' fees and the regulation of the relations between artists and art institutions. Such organizing initiatives also emerge in our local art world, for instance: the Orange Tent (Turuncu Çadır), an initiative of art professionals that meet regularly, and the Art is Organizing (Sanat Örgütleniyor), an initiative that aims to organize various art collectives founded in recent years.

Yet, what I am doing here is writing a text to voice an objection to these developments. While I do not oppose this 'politicization' in art, I think that it is essentially not related to what we have learned from Gezi and the Occupy movements, and it rather corresponds to a regressive politics. After all, where this politicization will take us will be no different from where it took Beuys: The National Parliament.

'Everywhere is Taksim; Everywhere Resistance'

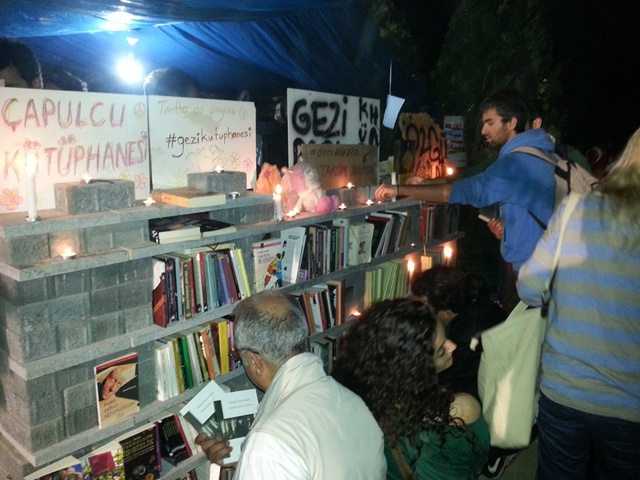

The politics that enabled Gezi to transform political language and depict politics in a different light was not a politics that would yield to being a parliamentarian. The relation between Gezi and art could be formed precisely as a result of the transformation of what is political. Gezi was not a moment when art took a go at politics by discarding art, it was an instance when politics came to art: when professional strategist political experts backed off and creativity transformed politics. The slogan 'Everywhere is Taksim, Everywhere Resistance' signified precisely that power was not composed of only one centre, one authority, and that politics did not just mean negotiations carried out by various professional mediators. It was a form of politics that diffused throughout the entirety of life. It politicized everyone and turned all into subjects who were not required to transfer their self-potential back to a centre or mediator through the presentation of a list of demands to an authority. These were subjects who attempted to transform life here and now with its free libraries, open kitchens, barter fests, 'Earth Tables'[1] – people who produced a form of politics that allowed each and every person to grow empowered and discover their own potential.

I don't have the opportunity to elaborate at length here, but the slogan 'Everywhere is Taksim, Everywhere Resistance' alluded to a politics often quoted by the art world – and also referred to as post-structuralist or post-humanist – in line with ideas of Foucault, Deleuze and Guattari. The weird thing here is that actors in the field of art in Turkey and the world appear to not have understood the difference between the ideas they quote, discuss and defend so wholeheartedly: that when it comes to activism and to organizing, they immediately retreat to the old language and form of politics.[2]

The politics of demand we are faced with – that is to say, the political language that tells institutions to regulate its relations with sponsors and artists – is much more regressive than the politics of Gezi. It is a politics that is based on representation mechanisms, that delegates politics to the theatrical empty gesture of the ideal ethical position and gives back what has been gained at Gezi through the transformation of what is political. It registers politics as the recognition of rights via certain positions of subjectivity: in short, a politics that makes the political bureaucratic. The trademark of politics of demand is grounded in the threat of a boycott. Using boycotting as a means of blackmail against institutions, the tactic of using art as a trump card at the negotiation table with institutions by setting forth various conditions is complemented by declarations and letters in which the ethical position is presented and explained.

This is an attitude that reasserts the old political language we thought we were free of, which used to undermine art (and life) as a form of doing, making and knowing, or by not problematizing everyday life itself as avant-garde longings.

It seems as if we are working with the following assumption when we begin to speak with this language – art and our artistic acts – the politics of creative action are no longer an issue; we have found the rights and wrongs, we can now look at the relations of institutions with sponsors and artists. Yet, these two spheres cannot be separated; they are completely intertwined. What makes the situation even more complicated is how art is being codified in a reductionist manner as a benevolent space of freedom of expression regardless of its content and form, and by extension, as a purely 'good' symbolic capital.

Let's proceed with the following example: An activist artist is making a work – an oil painting of a miner or a participatory, socially engaged group art project. The works of this artist are supported by and exhibited at the art institution sponsored by the mining company. The mining company hits two birds with one stone by supporting art with the capital it makes from the workers it exploits through the subcontractor system depriving workers from social security: it collects both financial and social/cultural capital. The artist's response to this situation is maintaining the same artistic attitude; defending his or her attitude as if drowning in the politically correct discourse she or he has constructed; not questioning her or himself; freeing her or his art and self from blame and placing it on the chain of relations of art institutions in society today. And yet this chain of relations is precisely what has brought activist art to where it is today, and thus precisely what has led to the support activist art works receive.

Calls for Boycott around the World and in Turkey

The 2008 crisis, Arab revolutions, and constant state of activism that has spread to different continents and countless countries such as Europe, the United States, China, Brazil, and Ukraine have made the estranging effects of what many deem to be neoliberalism and financialization even more visible. Even though so-called neoliberalism persists, no one advocates for neoliberalism any longer, nor can anyone claim there is no alternative to it.

At such a historical moment, we see more and more boycott calls and gestures of letter and petition drafting/signing in the art world demanding transparency in management; art institutions to sever ties with companies and capital violating human and nature rights; for states and companies to develop policies that respect human rights and nature. Supporting these demands, calls/threats of boycott emerge as the grounds upon which this political language and style comes to life.[3] Recent examples include the artist boycott against the exploitation of cheap migrant labour in the construction of the Abu Dhabi Guggenheim; criticism and demonstrations against Tate for BP sponsorship; the call for artists to boycott the 11th İstanbul Biennial prior the exhibition due to its sponsor Koç Holding's ties to the 12 September 1980 coup; once again with reference to its sponsors the demonstrations and boycott call against the 13th İstanbul Biennial opening up the question of the public space for discussion, followed by the letter by art workers addressed to IKSV and the curatorial team after the incidents that ended up at the police station; and most recently the boycott threat to the 19th Biennale of Sydney demanding it break all its ties with Transfield Holding, which builds immigration detention centres, and the Biennale severing ties with Transfield and artists who do/don't return to the exhibition.

Since the Abu Dhabi Guggenheim and Biennale of Sydney boycotts/threats were relatively successful, I would like to touch upon two problems this success raises and roughly present the political language these boycotts resurrect and the forms of subjectivity they activate.

1) The Boycott Paradox

All the artists who boycott exhibitions, or hurl threats of boycott, are politically and socially engaged activist artists. That is to say, artists who have an objective of making use of the exhibition as a space for political and social discussion and awareness raising, and who believe in its impact. (Though not all of them go on with the boycotts. For instance there are also artists who returned to the Sydney Biennale, which cut its ties with Transfield, after their demands had been met).

Driven by the instinct to defend the sphere of art and give it purpose, curators and artists adopt the discourse that art is an independent space of expression where an open public discussion can be carried out.[4] This argument seeks refuge in political correctness and is not all that convincing, because of limitations of access and participation in huge spectacles as biennials. Nevertheless, it is an argument that resonates in our ears as the presentation of a most compromising and tame notion of democracy.

There is an admission – a confession of the ineptness of activist art in the notion of the boycott being vibrant as a course of conduct. No longer able to stand the complicity of its position due to relations of capital, activist art suspends its belief in the potential of its art and the biennial exhibition as a medium of discussion. What's more, this gesture becomes effective in the discussion of democracy and human rights issues, making them visible and tangible – perhaps more powerfully than the exhibition and the works of art ever could. We made our boycott threat, and we were effective; a public opinion was formed, the Biennale ended its sponsorship agreement. In my opinion, this process and its relative successes further aggravate the problem of activist art. If the strongest gesture is boycott, then unavoidably the question comes to mind: why not carry it out to the end?

Then again, boycott is a method that should always be kept at hand to sustain the relationship with the capital or the state. It should not be discarded right away. However, the language of politics unleashed by boycott also turns art into a PR field where corporations and the state accumulate symbolic capital and artists are coded as bearers of this symbolic capital, in varying ranks depending on their career and degree of fame. I consider that for a state or a corporation to support art is also supporting democracy, freedom of expression, progressive politics, diversity, creativity, and so on. When an artist tries to push these ideas, and states and corporations act accordingly in terms of support, paradoxically what is accomplished is to offer states and corporations the opportunity to co-opt these values. In this context, a state or a corporation can claim symbolic capital, just because it offered a place for criticism.

Therefore, rather than certain institutions and capital establishments, it is this relationship dynamic that should be boycotted, for it codes art as a PR field and artists as symbolic capital subjects in a hierarchal structure. What we should be asking ourselves is not 'which corporation is legitimate?' but rather: how is art set up as a PR field, due to which of its qualities? What is the way to transform this relationship?

2) Who should be the Prince of Art?

Another problem exposed by this situation is this: with which money is art to be supported, which institution, company or state will artists support as the holders of symbolic capital? Seeing as there is no full-scale retreat or boycott from art and the field of sponsorship itself, then with what money are we to carry on working with? Seeing that art is an unsullied symbolic capital, a pure token of the freedom of expression, and that artists are the representatives of this capital, then to whom should this figurative capital be sold/given/relinquished? What should this representative capital be exchanged with? Today, this discussion has become inevitable. Should art be supported by the state, which develops and implements refugee policies in direct violation of human rights, or that has carried out genocides, espoused discrimination as a rule, and deems all sorts of oppression of the people appropriate? Is the state money collected through taxes and managed by a political party more clean? Which company does not use cheap and precarious labour? Which company does not profit from the consumption of fossil fuels? Which bank does not support the hydroelectric power plants that will bury historical artefacts under reservoirs, or make the rich richer by means of poisonous financial instruments? Which brand is against the genetically modified seeds, the incorporation of agriculture and stockbreeding, and privatization of natural resources? Which state or company develops policies respectful of various gender identities? Which clean, legitimate source of income will art support with its symbolic capital?

In short, how should we manage the 'trade of ethics' that we conduct by means of the art world and our representative position within that? This question alone manifests the sort of political language and position of subject the boycott tactic engenders.

Neoliberal Capitalism and Benevolent Activist Art: A Win-Win Scenario

Now let us step back a little further and look from within a certain historical framework. Especially over the last two decades, in the absence/debility of public institutions and social solidarity networks (unions, social security institutions, and so on) undermined by neoliberalism, activist art has been, and continues to be, supported by philanthropic gestures offered as compensation to these institutions that reside within a field (and discourse) determined by non-governmental organizations.

According to the neoliberal idea, society will remedy its ailments on its own. For instance, every individual is responsible for his or her health expenses, while a societal illness – on the other hand – will be rehabilitated by philanthropic foundations and funds. The ailments caused by the corporations that have gotten rich in free market economy will be remedied again with their own philanthropic gestures, of course only if they so choose. A result of this situation is our overall precariousness – as individual labourers within this system, we are left at the mercy of the powerful. Take, for example, the Soma mine disaster, and the fact that the company was not required to have rescue chambers.[5] In this case, you could say that in the absence of the social state having installed a rescue chamber would have demonstrated the company's benevolence, which would then bestow the company with a certain amount of symbolic capital. Benevolent activist art also, just like the rescue chambers, finds itself as an exploitable benefit, which any willing company can feed on. The company is not required to support activist art, if they do it is done solely by their grace, love and respect of art and its political discourses.

This may be business as usual. However, this is a situation (privatization of social services, undermining solidarity institutions such as unions, public healthcare, public education, unemployment insurance...) that has ensued with the dissolution of public institutions and spaces since the 1970s and the imposition of neoliberalism as the only and unrivalled ideology after 1990 and the fall of the USSR. And activist art produced over the last two decades – which has now become the mainstream in the art world – has lined its pockets in this process. The challenge of the situation is that the activist artist, which cannot find itself a place in the art market, has to be supported somehow. The state, corporations, foundations, municipalities, European funds, the World Bank, United Nations… Big, ambitious projects that cannot be small in scale and cannot be self-sufficient have to be supported from within this field of philanthropy, and must in turn find a way through this industry of deliverance. Paradoxically, the better the intention, the bigger the project gets and the easier it becomes to fall into the clutches of this philanthropy market. While striving to help the oppressed, make them visible and heard, activist art finds itself weak; prone to exploitation and manipulation and bargaining with the devil. Activist art that has a hard time explaining this situation to itself thus grasps at theatrical ethic gestures in order to cleanse itself from its 'unholy' bargaining so as to retain integrity: so you have letters, declarations and conditional boycotts.

Therefore, activist artists and researchers find themselves in an ethical wringer. The activist artist must often accept the 'devil's' deal and puts on its costume. Activist art's claim to cleanliness, benevolence and innocence is the basis, the sine qua non of the equation contrived for the 'devil' – institutions of the capital: sponsors, companies, corporations – to partake in benevolence and the symbolic capital of art. Activist art has to be coded as benevolent so that by supporting it the devil can take its share from the benevolence. This is a win-win deal. Exactly at this point the roles of the two – the corporate 'devil' and the artist, the good and the bad – meld into one another: art and capital can no longer be told apart. Activist art's blackmail of conditional or unconditional boycott, declarations and petitions are the last resort to find the means to continue playing within the same setting and script. In this sense, the boycott is not a retreat or exposition but a call to continue to the game.

Why do we love our chains?

While playing its role in a script drawn up by neoliberal, capitalist entities through notions of conciliatory democracy (such as transparency, recognition of human and nature rights), activist art is ultimately in the service of capital. Thus, the most obvious way of transforming the game is to reject outright the role of benevolent, innocent, politically correct, saviour artist. Rejecting this role is simultaneously the rejection of castings based on sharply demarcated dichotomies of good-bad and black-white. We do not have to be in the position of a clean and ideal good, or claim that we are even though we are not, or portray ourselves as wronged and weak as if we have no share or benefit in the game being played. The issue is not to symbolically refuse to participate in this or that biennial or exhibition, but to transform the very game that is being played with art. And the way to do this is to reject the role of the activist artist. Rejection of this role will open before us a field of possibilities where different roles and scenarios can be built outside the divisions of good-bad-victim, thus facilitating exit routes out of the ethical wringer.

We do not have to perform in the script crafted by neoliberal capitalism and benevolent activist art. Attempts to politicize the sphere of art by subordinating the activity of art are symptoms of regression to the politics that operates through representations. Other deviations that can be realized from within this script, without denying our role and initiative in the game, may be the subject of another article. However, let us be sure to mention that the activist art game does not have to be played within institutions of philanthropy supported by capital or the state. Artists can solve many problems through their own initiative and modest self-organizing methods, without demanding resources, recognition or rights from institutions or sponsors. The social legitimacy of self-organized, small initiatives spread across everyday life stands before us as a potential waiting to be activated. Demands for the recognition of rights and regulation of relations within capital create an effect that hinders the artists from problematizing the relationship they establish with their own productions, the politics of their works and their political stance, and imagining an alternative.

Why do artists pretend like they are doomed to these relationships? Why do we love our master? Why do we love our chains? Why are we so incompetent in imagining another politics? These stand as problems that need to be explored. The demand for the relationship between artist-art institutions, workers-factories/corporations, states-citizens to be regulated and improved seems doomed to remain as a regressive politics so long as it does not strengthen the efforts of self-organizing so as to gain autonomy without thinking about how to move beyond the field established by the rationale of philanthropy.

[1] Earth Tables are meals for breaking the fast during Ramadan on the street launched by the grassroots organizing of anti-capitalist Muslims, to which everyone is invited and brings food to share. See: 'Anti-Capitalist Muslims hold iftar in Taksim again under tight police surveillance,' Hurriyet Daily News website, 29 June 2014 http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/anti-capitalist-muslims-hold-iftar-in-taksim-again-under-tight-police-surveillance.aspx?pageID=238&nID=68419&NewsCatID=341.

[2] For a text in which I roughly outline how Occupy movements function with tactics of 'demand', 'demandlessness', 'chaos', and 'huge demand', see: Burak Delier, 'Gör Dediğimi Gör Ama Kanma!' (See What I Tell You to See But Do Not Fall For It), blog entry, Ne Yapmali blog, 12 July 2012 http://www.ne-yapmali.blogspot.com.tr/2012/07/gor-dedigimi-gor-ama-kanma.html.

[3] For the boycott of the Biennale of Sydney and its outcomes, see: Alana Lentin and Javed de Costa, 'Sydney Biennale boycoot victory shows that divestment works,' The Guardian website, 11 March 2014 http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/mar/11/sydney-biennale-boycott-victory-shows-that-divestment-works.

For the boycott call and petition against the Abu Dhabi Guggenheim, see: http://www.ipetitions.com/petition/gulflabor/.

For the call to boycott the Biennale of Sydney, see:

[4] For the statement of the 13th Istanbul Biennial curatorial team, see: http://bienal.iksv.org/en/archive/newsarchive/p/1/790.

For the statement of the curator of the Biennale of Sydney, see: Louise Darblay, 'The Biennial Questionnaire: Juliana Engberg,' Art Review website http://artreview.com/previews/the_biennial_questionnaire_juliana_engberg/ and Alexandar A. Seno, 'Interview: Juliana Engberg Defends Sydney Biennale,' Wall Street Journal website, 20 March 2014

http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304747404579446673957214280.

[5] The Soma mine disaster, which took place on 13 May 2014, is one of the biggest mine disasters in the history of the world. In the press statement issued after the accident, the company officials have stated that there is no requirement stipulated by the mining work safety regulation to provide 'rescue chambers' where miners can take refuge in and survive an accident. See: 'Turkish mine disaster: Soma firm denies negligence,' BBC News website, 16 May 2014 http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-27435869.