Essays

How Toshihiko Made Me Understand Islam

Who would have thought that the best translation ever to be conducted of the Qur'an was actually in Japanese? Many scholars agree that Toshihiko Izutsu's 1958 version of the holy book is one of the most accurate one available.[1] A linguistic genius, Dr. Izutsu finished reading the entire Qur'an just one month after beginning to learn Arabic. His idiosyncratic method of analyzing theology through language (his background knowledge of Zen Buddhism assisted this advanced outlook on other world religions) produced incredible insights into Islam that I have not heard with quite the same level of clarity and objectivity from any other scholar. Later in life, he went on to teach Islamic philosophy at several universities in Tehran, which hints at just how knowledgeable he became of the religion and its history.

Regrettably, many of his thought-provoking books have remained un-translated, and are only accessible in Japanese. Fortunately for me, my fluency in the Japanese language allowed me to penetrate this rare dearth of significant research with ease. When I first read his lecture-turned-book Islamic Culture (1991), everything in my life suddenly made sense. In my ten years living in Tokyo, it was by far the moment I felt most satisfied to have mastered Japanese.

Izutsu effortlessly demonstrated how the Qur'an was written in the prophet's own dialect (Quraishi); that the religion had many traits of the language of the marketplace (the prophet himself was a merchant); that the relationship between God and his subjects was a vertical relationship of a master and his slave ('Abd) also stemming from the market (Souk); that Islam follows a distinctly capitalist mentality (good deeds are referred to as 'earnings' and are counted, like money); that the scripture was written in the first person – in God's own words – an anomaly compared to other faiths; that Islam discarded with figurative representation because its language itself was the audio-visual medium (the 'images' are inside the words), making it one of the only truly 'abstract' religions. Indeed, the Qur'an refers to paganism, which preceded it, as 'that which does not see or hear.'[2]

After finishing Islamic Culture, I came to this conclusion: Islam is abstract expressionism through poetic illustration.

Like abstract expressionism, it is concerned with describing spiritual matters of the mind and soul by denying pedagogical figurative depictions (sometimes very violently so, by actively destroying pagan statues and objects), and pushing religious creativity beyond the superficial through the medium of language. If embodied pictures and figures are no longer necessary and are instead encapsulated within 'words' – oral or written – their ability to transcend physical spaces and material 'things' in general becomes infinite. The Qur'an is 'full of visual images from corner to corner'[3] that can simply materialize in the expansive arena that is the mind. It gives the believer (the viewer if spoken from an artistic standpoint) the luxury and space to imagine the visuals through the power of literary suggestion alone.

We usually attribute the philosophical structure of these artistic concepts such as visual abstraction to western modern art movements in the twentieth century. But in actual fact, they have been processed and developed through and within literary movements centuries before the advent of modernism. In the Arab world especially, literature and language were and remain the primary means of artistic expression, and have been so for centuries. It must be taken into account that part of this trend is strongly influenced by Islam as an institution of thought, and its philosophical developments over the years. It is only very recently that visual figurative art has become widespread in the region, which coincides with an enthusiastic attitude towards modern, individualistic, urban life.

However this city-dwelling lifestyle does not conflict with Islamic teachings. Izutsu also stressed that Islam was not the religion of the desert, and was based on a truly urban understanding of the world. As noted above, distinct aspects of city life (the market, money, slavery etc.) are apparent in the phrases and words used to describe religious concepts within the Qur'an. This fusion of natural and man-made environments with theology stunned my imagination. But here, I began to wonder – what if this urban disposition of Islam had changed in recent times? After some contemplation, I came to the realization that it has indeed changed dramatically. The advent of Wahhabism in the Arabian peninsula over the past two centuries has succeeded in returning Islam to the desert.

A large section of the book Islamic Culture is dedicated to deciphering the different prisms used to interpret the Qur'an, and how these prisms can become completely contradictory depending on their placement in the wider sphere of the Islamic Empire over time. Wahhabism – the official Sunni sect adopted by Muhammad Ibn Saud (the ancestor of the House of Saud, founders of modern-day Saudi Arabia) contains many traits of a desert mentality. And although initially a fringe sect, it is now the dominant expression of Sunni Islam in the Arabian peninsula, even though official accounts claim otherwise. Senior religious clerics state that this is the natural and ubiquitous form of Sunni Islam that permeates the entire Islamic world, but this is in fact a false claim. Sunnism is not quite as puritan or extreme as Wahhabism, and has many pluralistic interpretations of it existing all over the world. Nevertheless, Wahhabism's teachings have penetrated the culture of the Arabian Gulf far beyond the local populace's immediate comprehension.

One of Wahabbism's signature commandments is 'do not visit the dead', because such shrine or tomb visitations can inspire idolatry. The deceased must be forgotten, and their graves must remain unnamed, as is the case in desert life; you must not cry or show emotion over those who have left us. It is this kind of harsh puritanism that entails the desperate climatic surroundings of the desert, unlike Shi'ism for example, where the dead are revered and decorated in a Firdous-like (Garden of Heaven) atmosphere, and graves are blessed with sweets and water. Izutsu claims that Shi'ism is a fundamentally esoteric sect that is heavily influenced by Persian culture, where belief in symbolism and meaning are paramount, often embracing metaphysical concepts like the disappearance of the twelfth Imam Mehdi into a hole in time, and his subsequent reappearance before the day of judgment. This comes in opposition to Sunnism, which is an exoteric sect based mostly on personal conduct and behaviour: 'Shi'ism is illusionary surrealism, while Sunnism is atomistic realism.'[4]

Being half Sunni and half Shi'ite myself, these insights into the cultural difference of sects profoundly articulated my understanding of my familial background. The stark contrast between my ancestral Iranian and Saudi roots; the discrepancies between both of my families' beliefs, customs, and rituals could only be explained through Izutsu's sharp observations. I realized that there is a place where this phenomenon is most apparent: Sulaibikhat.

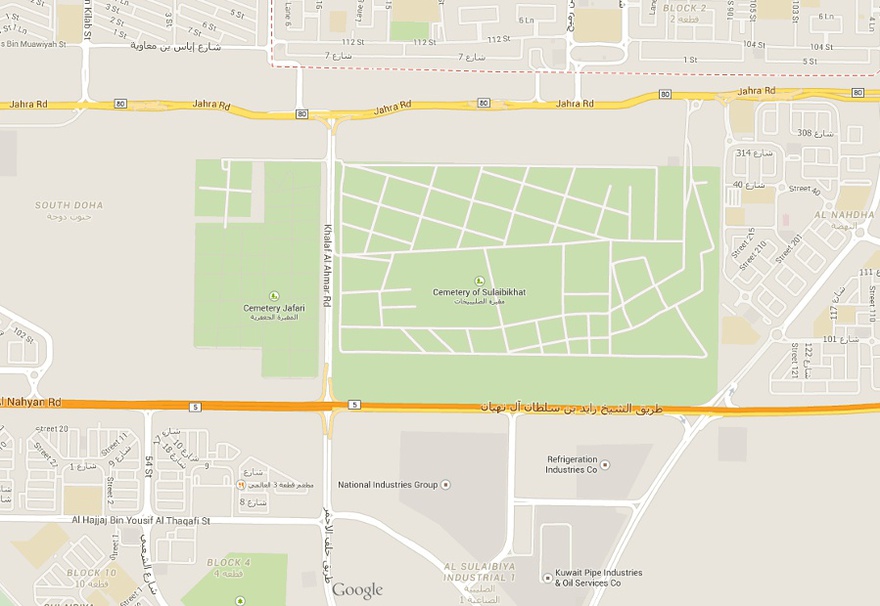

Sulaibikhat is the national cemetery in Kuwait (the only one currently in use) that was built around the early 1960s. On the one side of the cemetery is the Shi'ite graveyard, and on the other is the Sunni (Wahhabi) one. They are segregated only by a road cutting through the middle of the two graveyards.

Could this road be seen as the violent separation between the spiritual manifestations of Islam? Is this the border of irreconcilable, intolerable cultural difference? As is evident in the following maps and images, the doctrinal divisions are visually clear. The Shi'ite decorated garden is on the left, the nameless Sunni desertscape is on the right. It is as if a completely opposing philosophy on life and death can literally be 'pictured' here, without exerting any effort to uncover it. The banal asphalt path between the cemeteries transforms itself into the metaphysical boundary of thought, and neatly partitions these incompatible world views.

At the time when I was observing the discrepancies of these cemeteries, I was in the middle of conducting my research on the aesthetics of sadness in the region, and trying to uncover how grief is visually manifested within physical spaces (most of which were tombs and cemeteries) as a first entry into the subject. After much reflection on the difference of the two plots, I could not come to a definitive answer as to which one was more 'sad', so to speak. Is the beautiful celebration of death and constant visitation of graves on the left side more 'tragic' somehow, or the denial of remembrance of the dead on the right side more bereaved because of its abject sorrow at even the fleeting thought of those who have left us? I could not really say.

Prism (2007-ongoing)

Video & photo series

[1] 'Ḥilalī also intends to demonstrate the contribution of Izutsu's works to the cumulativeknowledge of Qur'anic scholarship. He wants to explain how the theoretical and practical principles presented by Izutsu 'add scientific and methodological value to the study and the understanding of the Qur'an, unveiling the precision and perspicuity of its verses'. He points out that the principles Izutsu introduced had their precursors in Arabic philology but had only been applied partially and did not allow the study of the overall structure of the Qur'an as a whole. For Ḥilalī, semantics in Izutsu's approach are more comprehensive than familiar sharʿī ('religious') concepts; they aim primarily to identify the nature of conceptual change, and how that has been employed in the Qur'an, bringing about a new worldview.' Journal of Qur'anic Studies 14.1 (2012): 107-130, 114. Edinburgh University Press DOI: 10.3366/jqs.2012.0039, Centre of Islamic Studies, SOAS, www.eupjournals.com/jqs.

[2] The Qur'an, 19.41.

[3] Toshihiko Izutsu, The History of Islamic Thought, (Iwanami Bunko: Tokyo, 1991, p. 18.

[4] Toshihiko Izutsu, Islamic Culture (Iwanami Bunko: Tokyo, 1991), p. 76-80.