Essays

Building in A-topia

1. Deterritorialization and imaginary homelands

This text is intended as a reflection on deterritorialization through the contemporary sentiment of displacement. Deterritorialization is a process that has traversed the entire history of Modernity, and it implies the transformation of the relation to the territory. Displacement is the abandonment of a physical place and the transfer to a different one. Deterritorialization is the anthropological effect of displacement that is not only geographical, but also linguistic, affective, aesthetic and so on.

In their book A Thousand Plateaus Deleuze and Guattari call deterritorialization the main trend of Modernity. People are pressed to leave their countries, their homes and their acquaintances in order to take part in the general mobilization of industrial production, colonization and war. We have witnessed this as inept spectators of events including the massacre of Yarmouk in spring 2015, the umpteenth episode in the interminable ordeal of the Palestinian people. Simultaneously, we witness the deaths of black men in American cities: white policemen expressing an American unconscious that has never accepted the reality of multiculturalism. In Italy, where I live, we watch the horror unfolding over the Mediterranean Sea, as thousands of corpses lie underwater: Africans, Arabs, and Asians who all try to pass the Sicily Canal on makeshift boats. They have been rejected by the European Union: killed by the legal cynicism of Frontex, the Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union.

We may argue that deterritorialization is the condition of knowledge, creation and erotic involvement with the Umwelt. Umwelt is the German word referring to the world inasmuch as the world is the surrounding environment that is projected by our minds, and which simultaneously stimulates our mind and influences forms of understanding. We may also argue that deterritorialization is a process of disturbance of the Umwelt: of our relation to the territory both in the physical and in the psychological sense.

You might say we are trapped in what Salman Rushdie calls 'imaginary homelands'[1]. An imaginary homeland is the idea that a place we identify as where we belong is actually only the projection of our perception of belonging. We live in a place, and we think that it is naturally 'ours', even if in actuality we don't belong to any place: yet we need room for our existence. This is not a homeland, it is quite simply the space necessary for life.

Today, people are not suffering from being uprooted: human beings are not trees – they are sentient rhizomes that proliferate and connect. Yet they do suffer from the obsessional need for identity, which implies exclusion, subjugation, and finally, violence and expropriation. They are suffering from the scarcity of space: an effect of political and economic violence that destroys the very possibility of self-expression.

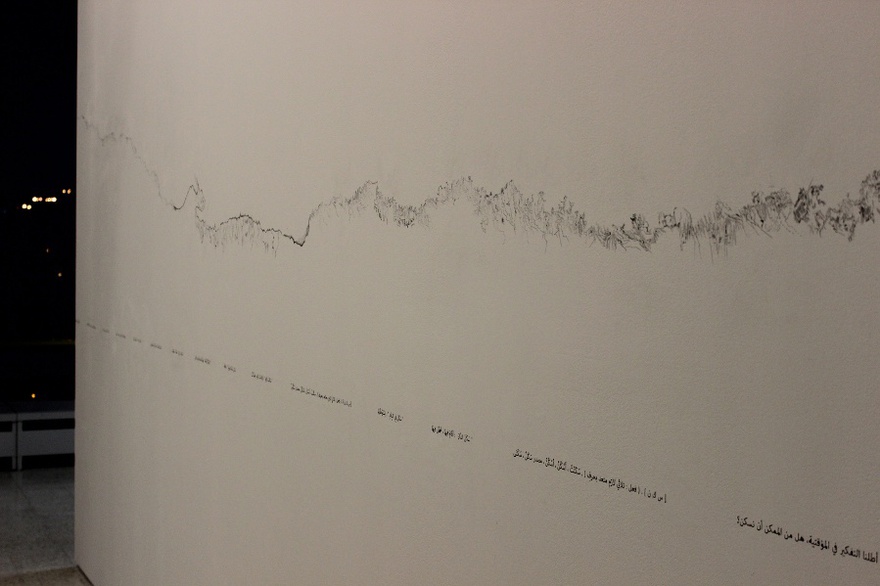

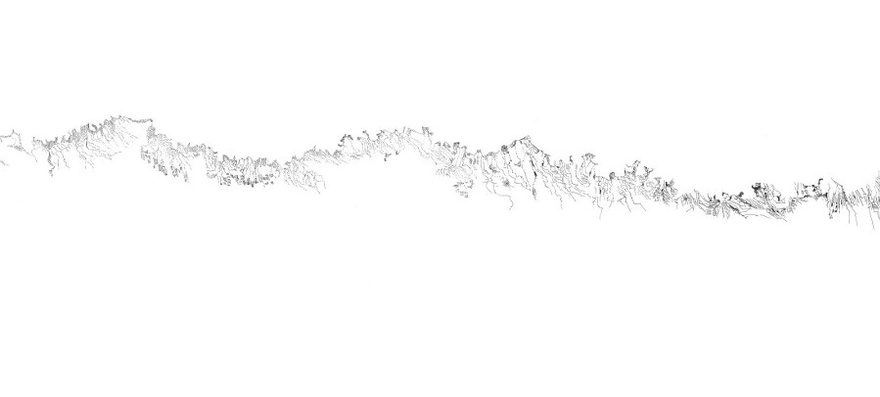

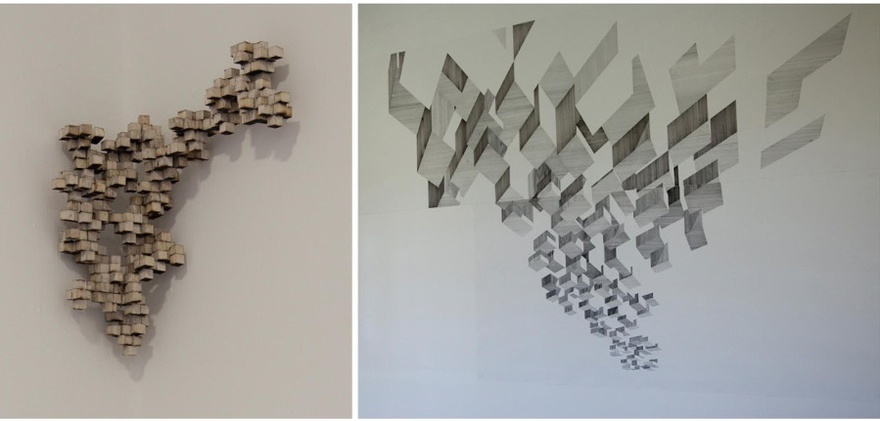

This is described in the work of Palestinian artist and architect Saba Inaab, who considers deterritorialization and alienation to key themes in her practice. These emerged some years ago, when Inaab was recruited by UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine refugees in the Near East): her task was the reconstruction of the Nahr el-Bared Palestinian refugee camp in northern Lebanon, previously destroyed by the Lebanese Army after a conflict with an Islamist fundamentalist group, Fatah al-Islam. This engagement invited Innab to rethink her own life experience and particularly her professional activity. From these reflections an art project was conceived: How to Build Without a Land (2011–ongoing). In this project, which is composed of text-based elements that – as Inaab has written – move between the poetic, scientific and the hallucinatory, Inaab constructs a spatial narrative. She explores variable notions of "building," whether by the physical construction of an object, or by building with language. Innab does not claim identity: the spread of identitarian obsession is the counterweight of a condition of deprivation – of land, of space, and of liveable life. Identity comes up as a sort of vengeance: an effect of resentment. Some of her images are excruciatingly intense: land and sky are subverted, as the earth is traversed by geometrical lines of military imprisonment becomes to the sky to the grey below. Some are abstract and frail: a disturbing imagination of upside-down architectures that can be perceived simultaneously as dystopian description and as utopian commitment to build in the heaven of perfect abstraction, where history and violence are forgotten, forever evaded. Although conceived in the particular situation of a Palestinian camp, the images resound with the tragedy of countless people who share the same sentiment of permanent dislodgement: refugees, migrants and precarious workers who are refused a place in the world.

In Innab's work, I see a dramatic reflection on the space of life and death. Simultaneously, however, I also see the attempt to overcome distress: to rethink building and dwelling in conditions of precariousness and temporariness. More broadly, I may say that the project is about life and death in a state of suspension. In Innab's words:

When we die we become the death and the land. The question remains, how do we die if we live out of place, in other words, how do we die if we live only in time?[2]

Painful temporariness is produced by landlessness:

Landlessness is signified by the land of Palestine, and by extracting the land from someone as an adjective that he/she becomes landless, landlessness is signified by the presence of the absent.[3]

These images outline the pain of the contemporary a-topian condition, which finds its epitome in the Palestinian exodus: the outcome of a violent aggression, which has provoked the suspension of the relation between the Palestinian body and the territory that was the room for a liveable life. The violent eradication of bodies has provoked an effect of humiliation that resounds in the transformation of the Palestinian soul. Rage, aggression, and terrorism have been nurtured by this original removal.

2. Turning the world into hell

Cultural deterritorialization is inherent to the Modern condition, enhancing imagination and enriching daily life. But when people are obliged to live the process of separation of the perceptual soul from the environment that the soul recognizes – deterritorialization in conditions of landlessness and of precarity – despair and violence predictably follow.

When, at the Conference of Versailles in 1919, Chaim Weizmann said that Jews had a right to land in Palestine because 'memory is right' he entered into a bottomless trapdoor. He opened the Pandora's box that has destroyed countless lives and has laid the foundations of a neverending history of violence. The establishment of the Zionist State has been marked by the brutal expulsion of millions of Palestinian people from their homes and an attempt to cancel the memory of the Palestinian people. But memory does not disappear. Rather, it produces its monsters, obsessions, and traps. Both Israeli and Palestinian memories have changed shape from resentment to misery, hatred and war. This has put Israel into a state of permanent guilt and of permanent danger.

In June 2014, the UN refugee agency reported that the number of refugees, asylum-seekers and internally displaced people worldwide has, for the first time since the post-World War II era, exceeded 50 million people.[4] The population of refugee and displaced Palestinians is the largest in the world. In 2012, the number of registered descendants of the original Palestine refugees was estimated to be at around five million.[5] A large part of this population is registered and assisted by the UN World Refugee Agency in 58 camps. Their right to return was recognized in the United Nations Resolution 194 in 1948, after the war that resulted in the expulsion of around 85 per cent of the Palestinian population at that time.

Recently, American columnist Nicholas Kristoff, winner of two Pulitzer prizes and 'honorary' African citizen, visited Gaza. He wrote:

It is winter in Gaza, in every wretched sense of the word. Six months after the latest war, the world has moved on, but tens of thousands remain homeless, sometimes crammed into the rubble of bombed-out buildings. Children are dying of the cold, according to the United Nations. Rabah, an eight year-old boy who dreams of being a doctor, walked barefoot in near-freezing temperatures with his friends through the rubble of one neighbourhood. The United Nations handed out shoes, but he saves them for school. For the first time in his life, he said, he and several friends have no shoes for daily life. Nearly everyone I spoke to said conditions in Gaza are more miserable than they have ever been – exacerbated by pessimism that yet another war may be looming.

Lacking other toys, boys like Rabah sometimes play with the remains of Israeli rockets that destroyed their homes. Gaza has been compared to an open-air prison, and, in the years I've been coming here, that has never felt more true, partly because so many Gazans are now literally left in the open air. But people joke wryly that at least prisons have reliable electricity.[6]

The columnist recounts something Rabah told him, an appalling expression of the hellish cycle of terror and terrorism engulfing Palestinian and Israeli existence: 'Maybe we can kill all of them, and then it will get better,' Rabah said in the report. Kristoff asked him if he really wanted to wipe out all of Israel, and he nodded. 'I will give my soul to kill all Israelis.'

3. Trapdoors into a bottomless past

In the sphere of contemporary globalization, where different cultures and different sensibilities are increasingly melting together, imaginary homelands can become trapdoors. In his last book, Judas, Amos Oz, though defining himself a Leftist Zionist, questions the rationale of the Zionist choice to build a state. In order to build a state, he says, we have provoked a permanent situation of war, hatred and fear, which implies the eradication of people who have been obliged to roam the world for the last 60 years. Noting that the effect of this apparently unending conflict is the moral corruption of Israel itself, the writer speaks of betrayal as illumination. Oz questions the fundamental problem of identity, and simultaneously denounces the dangerous definition of a state based on Jewishness. For him, the confessional identification of the state fuses nationalism and racism, and is paving the way for endless disgrace.

Take the literary and theoretical writings of V.S. Naipaul: the best introduction to the notion of identity traps. In Naipaul's works, it is possible to retrace the pathway from individuation to identification from the point of view of the emotional loneliness of the post-colonial nomad, the person who wanders in the world looking for a place that cannot be defined as homeland, but rather as cultural place for self-identification.

His books speak of a sort of repulsion that human physical presence is arousing, and the subject of his writing is often the erotic (mis)feeling and (dis)pleasure that the proximity of bodies provokes in his deeply rooted Brahmanic subconscious. When he was awarded with the Nobel Prize for Literature some years ago, Naipaul was accused of racism, but I think that this accusation is erroneous: the true meaning of his works lies in a sort of almost physical self-revulsion. Though Naipaul apparently despises individuals and groups that he meets during his travels in the world, what is more intolerable to him (and sometimes he is explicit on this point) is his skin, body, face, story and past. A good definition for this paradox of identity is found in Naipaul's book India: A Wounded Civilization:

In India I know I am a stranger; but increasingly I understand that my Indian memories, the memories of that India which lived on into my childhood in Trinidad, are like trapdoors into a bottomless past.[7]

This is an interesting definition when thinking about the concept of identity and belonging: trapdoors into a bottomless past. Searching for identity is a useless and dangerous game: you enter into a trap that shapes a perception of the other as both obstacle and enemy.

Identity and belonging are the psycho-cultural arrangements historically poisoning the relation between people who have different memories yet share the same territory. The history of the Arab-Israeli conflict is the demonstration of this overlapping of identity (identification), projection of belonging, and the need for territory. Nostalgia is not always based on memory, sometimes it is based on the phantasmic imagination of the past: retrospective projection. The need for belonging is often excited and intensified by the evidence that identitarian roots are self-confirming falsifications and generally act as self-fulfilling prophecies.

But is it possible to build in an a-topian space? Is it possible to transcend identity and create community on the basis of non-identitarian values: desire, culture, imagination? This is a difficult and urgent question that we must answer if we want to overcome the present spread of hatred, terrorism and war.

[1] See: Salman Rushdie, Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticism 1981-1991 (London: Penguin Books, 1991).

[2] Saba Innab, 'How to Build Without a Land', Urgeurge website, http://urgeurge.net/2015/04/11/how-to-build-without-a-land/.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Harriet Sherwood, 'Global Refugee Figure Passes 50m for First Time Since Second World War', The Guardian website, 20 June 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/20/global-refugee-figure-passes-50-million-unhcr-report.

[6] Nicholas Kristoff, 'Winds of War in Gaza', The New York Times website, 7 March 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/08/opinion/sunday/nicholas-kristof-winds-of-war-in-gaza.html?_r=0.

[7] V.S. Naipaul, India: A Wounded Civilization, (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1977), p.10.