Essays

Towards a Spatial Imaginary

Walking Cabbages and Watermelons

Over fifteen years ago, Chinese artist Han Bing initiated a social project by walking a cabbage on a leash. The cabbage, 'a quintessentially Chinese symbol of sustenance and comfort for poor Chinese', interrogates social values by ridiculing the state of things.[1] His performance proposes a reconsideration of the general lack of engagement with systems that have perpetuated a culture of consumption. It critiques systematic control of the public as much as it brings awareness to the utility of public space by addressing structures in place that are no longer being challenged. Through his performance, Bing asks people to 'question the definition of "normal practice", and to reflect on how much of our daily lives are routines we've blindly absorbed'.[2] While humourous, his approach poses a serious confrontation of the spatial constructs of territory where walking the cabbage initiates a critical mapping of physical space.

Inspired by Bing's performance, the Kashmiri Cabbage Walker uses the cabbage to confront the embedded military presence and post-political conditions of Kashmir: 'I, as a Kashmiri, am willing to recognize walking the cabbage as part of the Kashmiri landscape, but I will never accept the check posts, the bunkers, the army camps, the torture centres, the barbed wire, the curfews, the arrests, the toxic environment of conflict and war, as part of the same'.[3] The artist's flirtations with mechanisms of control and oppression deny the power structures in place where walking the cabbage becomes a political act that exposes the system: authority is ridiculed and potentially rendered weak for being humourless about a vegetable being dragged across the street. However, in the age of technological warfare with drones and remote systems of tracking, the act of walking no longer poses a critique on the constructs of space alone, but also exposes how monitored the body has become in the public sphere, particularly in territories of conflict.

Andrew Hewitt suggests choreography as a space to reinvent the boundaries of aesthetics and politics. His notion of social choreography 'seeks to aesthetically instil a social order directly at the level of the body'.[4] Before the cabbage walkers there were the Situationists, also walkers, using practices in psychogeography to critique advanced capitalism and commodity fetishism by denying the imposed socialisation of space in 1950s Paris.[5] Their attempt to reconfigure the urban socio-cultural fabric through city interventions, hijackings, diversions and irony profoundly influenced generations of artists searching for conceptual spaces or places of otherness that escape the structures of oppression and authoritarianism. Indeed, the genres of critical spatial practices and critical geography have become particularly relevant in contemporary art discourse for artists who are confronting the tensions of the nation state and re-imagining the construct of nationhood. Using art as a form of political engagement, these artists are addressing the ramifications of contested space to cultivate critical analyses of the diverse constructs of territory, both real and imagined, and are bringing to the forefront the social consequences of spatiality.[6] Indeed there is a long tradition of artists who have used creative tactics, or artivism, to transform urban sites into places of resistance. Can art, in fact, mobilise change? And should we be expecting this from art in the first place?

Five years ago Arab youth sparked an uprising across the region that later deemed the public sphere incapable of fulfilling the demands of its protestors. The conditions that originally prompted widespread unrest got significantly worse in almost all cases. The Middle East and North Africa today is a region undergoing drastic transformations especially as it relates to recent wars, uprisings and waves of mass migration; the unprecedented mass movement and displacement of bodies has undoubtedly altered the public realm. This perpetual state of fluctuation of the last five years has also brought with it new geographies of activism that have had a profound impact on the relationship between aesthetics and politics. Egypt's uprising, in particular, fostered a political collectivity through creative tactics and participatory tools on social media in one of the largest interactive revolutions to date. Across the region, artists and activists have been using a combination of creative and political practices to reclaim public space through various forms of social critique, not unlike the strategies of the Situationists. We have witnessed political expression through street art, viral memes, video initiatives, film, music as well as performative practices in public space. While the tradition of culture activism emerges from an urban context, its potential today relies heavily on the non-geographies of technology.

Social media, in particular, has allowed us to access the public on a much broader scale than ever before. Middle Eastern politics has permeated the public sphere through social media platforms that have allowed us to cultivate an enormous database of real time diaries. While user-generated content has significantly transformed how we analyse the region, it remains questionable how authentic and real user-generated content really is. The saturation of our communication technologies has underscored the need to produce and consume personalised forms of historical knowledge; the Internet, in general, is above all a tool to market memory. In the post National Security Agency (NSA) surveillance cyber landscape, however, we have become more aware of the contradictory nature of how these technologies are disguised in their utopian promises of democratic expression. The commoditisation of our communication tools has, as we have come to see, the potential danger of controlling our historical memories and re-writing our narratives altogether. Social media platforms pride themselves on providing a voice for the people while at the same time supporting the same paradigms that suppress public expression. In many ways, new media has become a means of control rather than emancipation. Who is held accountable when people are detained for expressing their opinions democratically online?

Today people are increasingly disconnected from the inner workings of the public realm due to the opacity of technological architectures that dictate how the body functions in space. The truisms of modernity are being tested through the cyber-technological control of movement and complex systems of surveillance. If we can't explain our technological systems then we can't critically engage them. The implicit trust of technology is subverted: we are dealing with the problem of obscurity as governments and corporations limit our access to information that, in turn, enables strategic decision-making. Ultimately, as a public, we must fully understand space through the canons of technology to avoid perpetuating and legitimising the systems that control it. Can public space itself be transformed into a form of alternative media?

The Arab public sphere proved to be vulnerable as institutions, artists, and activists are increasingly censored across the region in the name of 'protecting public morals and state interests'.[7] As a result, cultural production in the Middle East and North Africa has undoubtedly shifted. Artistic freedom is not a given right in the context of political paranoia even though, according to the United Nations, it is an 'essential component of human development'.[8] With a zero tolerance policy towards any creative expression that criticizes authoritarian rule or challenges social norms, it is clear that art is deemed a threat. The Freemuse organisation reports violations on artistic freedom around the world in collaboration with the UN Human Rights Council; according to their annual report, Iran, Syria, Turkey, Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia were among the top twelve countries worldwide with violations on artistic freedom in 2015.[9] Their governments function as gatekeepers with strategic legislation put in place to monitor public order. How can a region thrive with an active assault on critical thinking and creativity? A growing culture of paranoia has eliminated any radical positions outside of a consensual pluralist order and institutionalised policymaking. Consequently, politics has been reduced to the managing and ordering of public space.

The performance art group, The Center for Political Beauty confronts the crisis of state ownership of the public sphere. Through their practice, the group critiques reductive politics by addressing the failures of the nation state and its border policies through performative actions. Their project, 'The Bridge', interferes in the migration process with a landscape intervention of 1000 installed rescue platforms equipped with items potentially needed by migrants stranded in the Mediterranean Sea. The group further proposes a bridge from North Africa to Europe as 'a lifeline between two continents'.[10] Their point: we will do the work that governments ought to be doing to save countless lives and maintain human dignity. Other artistic research groups like Forensic Architecture address systems of surveillance and ambiguous border politics through heavily researched and designed narratives. In what has famously become known as 'The Left-To-Die Boat' case in which sixty-three migrants drowned in the Mediterranean Sea despite several distress calls to various authorities, Forensic Architecture aims to visualise the ways in which technological systems are set up to serve a particular agenda that reinforces the problematic constructs of the nation state.[11] They confront the issue of government accountability by constructing truths through laboriously compiled and meticulously visualised evidence. While one cannot argue the proactive nature of these aforementioned projects, an unresolved discomfort remains between 'voyeurism and human enlightenment in the aestheticisation of wretchedness'.[12] Is this even art? When the spatial imaginary overlaps with reality, does this not dissolve the illusion of art?

The discourse of aesthetics is political. Politics cannot be extracted from the aesthetic and the aesthetic cannot be extracted from politics, yet we cannot expect artivism to modify aesthetic sensibilities or go beyond disturbing the collective consciousness. Rather it should ensure a re-envisioning of the role of place and identity in shaping cultural autonomy. Culture activism has been used as a mechanism of resistance for centuries, especially in the Arab world. Anti-colonial Arabic poetry, for example, was one of many ways in which artists subverted their own media to critique oppressive rule. Early twentieth century Egyptian poets like Mahmud Sami al-Barudi, Ahmad Shawqi and Hafiz Ibrahim utilised anti-colonial rhetoric and criticism embedded in their writing by testing the ignorance of their colonisers.[13] Egyptian playwrights and actors also staged openly political Arabic adaptations of Shakespeare to protest British control of the country during the First World War.[14] These tactics are not unusual as strategies for political dissent; we have been seeing them across the region in the context of colonialism, war and revolution. It is still questionable, however, how connected the realities of social and political struggle are to aesthetics; can artists enable a revolutionary cultural politics that connects art to social movement?[15]

Many are starting by reclaiming their narratives abroad and addressing the complex relationships between dictators that impose systems of oppression and the military industrial complex that enables them. Activists from London Palestine Action, for example, posted 'subvertisements' (subversive advertisements) in London's underground tube network critiquing Israel's apartheid policies. In a statement the activists claim 'Israel and its supporters are used to having the mainstream media repeat their talking points. Our action's aim is to shine a spotlight on the support that Israel receives from the UK government and arms industry and UK companies like G4S as well as the one sided reporting which is endemic in the BBC'.[16] Their project attempts to alter local politics by speaking to foreign players. Considered as a form of culture activism, the subvertisements shed light on the impact of globalisation and neo-liberalism on local politics.

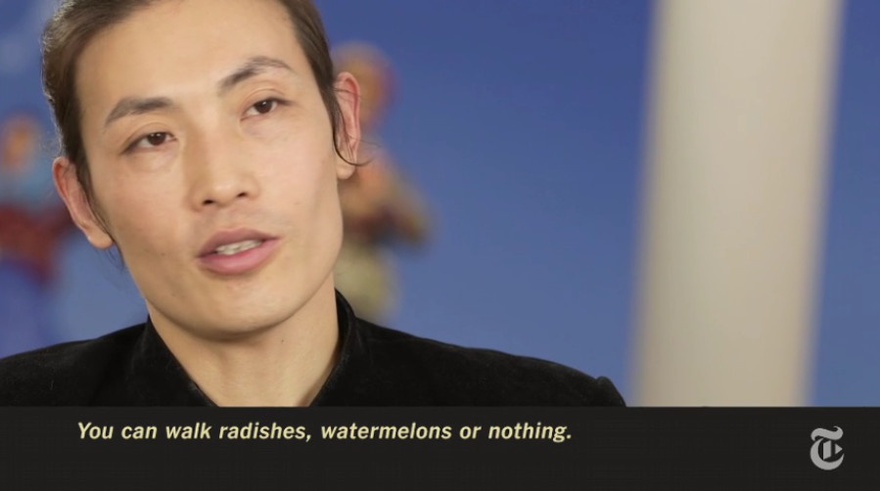

I write this essay having been involved in an act of culture activism myself. Along with Caram Kapp and Don Karl, the three of us adopted the ironic label of the 'Arabian Street Artists' and seized an opportunity when we were hired by the popular American TV series 'Homeland' to decorate the set of a Syrian refugee camp with authentic Arabic graffiti. To expose the creators' deeply flawed knowledge and understanding of the region in which their series supposedly takes place, we used humour to subvert the content of our graffiti to protest the show. Homeland later aired while unknowingly critiquing itself with Arabic tags like 'Homeland is racist', 'Homeland is not a series' and the widely popular 'Homeland is watermelon'.[17] Our act was about reclaiming local narratives and speaking to the very audience whose governments directly impact our local affairs. To our surprise, our 'Homeland hack' resonated on such a massive scale that it was front-page news in some of the world's major newspapers and media platforms. It initiated a worldwide discussion about the impact of the entertainment industry on global perspectives and foreign policy.

Do such acts have the power to produce meaningful change? While it is doubtful that they will have a direct impact on, say, Israeli policy or even Hollywood scripts, it is clear that creative practices such as culture jamming, subversion, laughtivism, hacking, public art and performance are able to reconfigure socio-political constructs in public space. They may not necessarily have a direct impact on politics but, at least, they can shift the way people see. Many artists and activists see it as their duty to exploit the constructs of techno-ideologies and resist dominant narratives of oppression. '[T]he function of the aesthetic sphere has always been to articulate the possibility of another way of life'.[18] Interestingly, the art world is one of the few spaces left in the region where criticality can still occur, where spaces of un-representation and data-less zones can be explored. Is artivism worth pursuing as a mechanism or is it just a tool that uses media to heighten the public's consciousness? Should we be seeking a 'revolutionary' aesthetic?

We engage in a performance of rehearsed social order on a daily basis where "the formal medium cannot be abstracted from the medium through which subjects experience themselves".[19] By re-envisioning an everyday act, the cabbage walkers turn performance into an anthropological concept focused on radicalising the public sphere. '[T]he freedom of bodies to move through space [i]s the very basis of political freedom'.[20] The aesthetic of everyday movement itself can be revolutionary. Today, much of the Arab world finds itself under more aggressive suppression where artistic expression has become a liability. Under authoritarian rule and a complete elimination of the public realm, what alternatives do citizens have to express opposition? How can they use their bodies in everyday acts of protest? In an interview with the New York Times, Han Bing encourages people to join his movement of walking cabbages or other appropriate vegetables as a form of protest.[21] In response to his call, I have decided to join the ranks of vegetable walkers with a watermelon, a symbol used in parts of the Arab world to describe something as a joke or a sham. Perhaps such a gesture can create a momentary schism in our political realities, or at the very least allude to a much-needed spatial imaginary.

[1] Han Bing, 'Walking the Cabbage', hanbingart.com. Web. 23 Mar. 2016.

[2] Maya Kóvskaya, 'Eroticizing the Everyday: Possession, Desire, and Everyday Dramas in China', hanbingart.com. Web. 23 March 2016.

[3] Parul Abrol, 'Walking a Cabbage in Kashmir-to Protest the Absurdity of War', Narratively. 2016. Web. 23 March 2016.

[4] Bojana Cvejic and Ana Vujanović, Public Sphere by Performance. (Berlin: B_, 2012). p. 57.

[5] Psychogeography is an approach to geography that emphasises playfulness and 'drifting' around urban environments.

[6] Building on the theories of Michel Foucault and Henri Lefebvre, Edward W. Soja proposes the concept of Thirdspace that suggests a critical and interdisciplinary way to address socially produced space through the 'rebalanced trialectices of spatiality-historicality-sociality'.

[7] 'Art Under Threat', Freemuse. 2015. Web. 9 April 2016.

[8] Ahmed Ezzat, Sally Al-Haqq, and Hossam Fazulla, Censors Of Creativity: A Study Of Censorship Of Artistic Expressions In Egypt. Cairo: N.p., 2014. Web. 15 January 2016.

[9] 'Art Under Threat', Freemuse. 2015. Web. 9 April 2016.

[10] 'The Jean Monnet Bridge', politicalbeauty.com. Web. 23 March 2016.

[11] 'The Left-to-Die Boat – Forensic Architecture', Forensic Architecture RSS2. Web. 15 November 2015.

[12] Stefan Roemer, 'The Intere-esse When Pressing the Shitter-Release Button', The Militant Image Reader. Urban Subjects, eds. (Graz: Camera Austria, 2015). p. 59.

[13] Kevin M. Jones, 'How protesters used Arabic to subvert Western influence – long before the 'Homeland' graffiti', The Washington Post. 2015. Web. 20 March 2016.

[14] 'The Arabic Shakespeares: Subversive, political, and entertaining', The New Arab. 2016. Web 19 June 2016.

[15] T.J. Demos, 'The Post-Militant Image', The Militant Image Reader. Urban Subjects, eds. (Graz: Camera Austria, 2015). p. 42.

[16] Asa Winstanley, 'Israeli fury at unofficial ads in London Underground', The Electronic Intifada. 2016. Web. 7 April. 2016.

[17] 'Arabian Street Artists' Bomb Homeland: Why We Hacked an Award-Winning Series', hebaamin.com. 2015. Web 27 March 2016.

[18] Andrew Hewitt, Interview by Goran Sergej Pristas. 'Choreography is a way of thinking about the relationship of aesthetics to politics', thefuturecrash.wordpress.com. Web. 5 April 2016. p. 4.

[19] Ibid, p. 3.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Han Bing, Interview by Kessel, Johah M. 'Cabbage as Culture', The New York Times International. Web. 21 April 2016.