Essays

Against the Market

The Art of Shirin Neshat

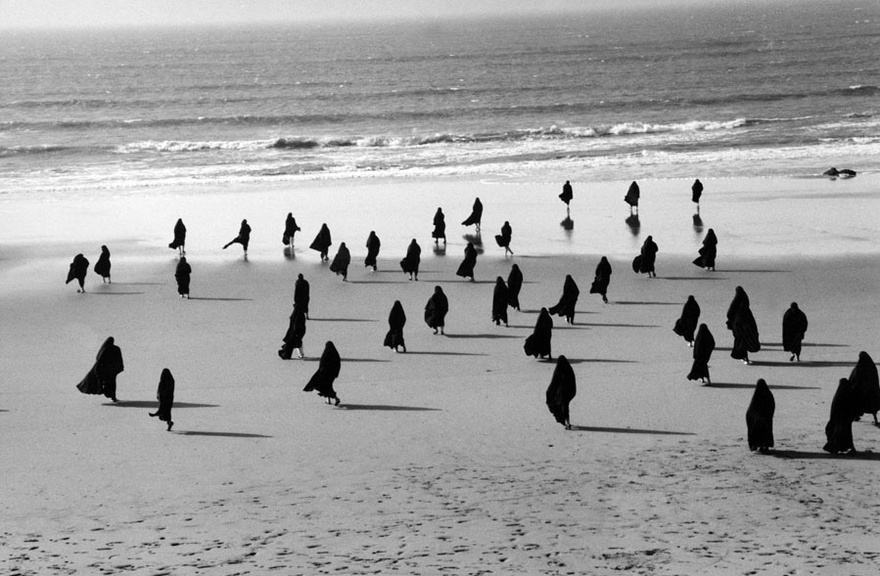

'Will Iran's Art Market Go Nuclear?' This shrill headline appeared in the summer of 2015 in the Observer above a black and white photograph showing a group of women in windswept black veils walking on a beach towards the sea.[1] The image is from Shirin Neshat's Rapture series (1999). The prospect of sanctions against Iran being lifted in the wake of the successful P5+1 nuclear negotiations led to a wave of articles focused on the Iranian art market. The brief article, to which the above-mentioned headline was attached, speculated on the impact of diplomatic openings on the Iranian art market in light of 'new record highs at auction'.[2] The inclusion of a still from a work by Neshat to illustrate the report seems a natural choice given that at the time the Hirshhorn Museum had a major exhibition of her art; that she is one of the most commercially successful contemporary artists from Iran; and that her works have had dramatic auction results.[3]

On 31 October 2007, Christie's held their third auction of international modern and contemporary art in Dubai in a posh ballroom in the Jumeirah Emirates Towers Hotel. Among the artworks for sale were four photographs from Shirin Neshat's Women of Allah series (1993–97). A surprisingly ferocious bidding war ensued, driving the artist's prices 'above the 100,000 dollars line for the first time'.[4] When the hammer went down, the photograph Guardians of the Revolution (1994) sold for $241,000 – more than triple its high estimate. A few months later, in April 2008, Christie's again offered a Neshat photograph in their Dubai auction – an artist proof of the 1997 piece titled Whispers. Shattering market expectations, it sold for $265,000, more than double its high estimate.

On the face of it, the story in the Observer might seem to confirm a particular truism: that the market has played a formative role in the field of contemporary Middle Eastern art more broadly and in the career of Shirin Neshat specifically. Through a historic confluence, a decade ago the first edition of Art Dubai took place the same year that Christie's held their first art auction in Dubai. Without doubt, the two institutions have become pillars in the Dubai art scene, further stimulated by dozens of independent art galleries that have established the city as a central capital of the art market. But the fetishization of the market in the narrative of the art of the region can obfuscate other dynamics that have shaped the careers of regional artists. There are other stories to be told about Shirin Neshat's iconic Women of Allah series. Stories about a young artist struggling to find her way by experimenting with form and content; about the enmeshed politics of art, gender and exile; about the intersection of literature and the arts; about the extension of the cinematic into photography; and about the dissonance of translating images across cultures.

In this essay, I make a specific argument against the predominance of the market in analyses of Middle Eastern contemporary art by tracing the exhibition history of Neshat's Women of Allah photographs throughout the 1990s. By following the photographs it is possible to map a creative network that anchored Neshat's career as an artist. In this story, curators and critics, independent art spaces and alternative galleries, university museums and academics, and a community of fellow artists played a central role in helping to establish the artist as a major figure in contemporary art.

This trajectory of Neshat's artistic career was not incidental. She studied art at the University of California, Berkeley, where she received a BA, an MA, and an MFA. Moving to New York in the 1980s, she became involved with the Storefront for Art and Architecture, a non-profit art organization. For nearly a decade, she helped run Storefront with her ex-husband, Kyong Park. She curated exhibitions, organized conferences and learned about the art world.[5] Neshat recalls:

This became my true education in terms of understanding how creative people actually function. There was also the Storefront's premise of mixing social responsibility and real life with the aesthetic. When I found my subject, which was the country of Iran and also myself, it was a perfect model for keeping the aesthetic and the personal part of the work in mind while also dealing with the reality of everyday life.[6]

The impetus for the series Women of Allah came from her first visit back to Iran following the 1979 revolution. Not only had Neshat been away from her home for a decade, she was returning to a completely changed country – an Islamic republic that had gone through eight years of war with Iraq. The visual shifts – highly gendered and militant – were startling for Neshat, who undertook a series of performative photographs exploring the politics of representation in such a heady context. In an artist statement that accompanied some of the photographs in the feminist journal, Signs, Neshat described the works:

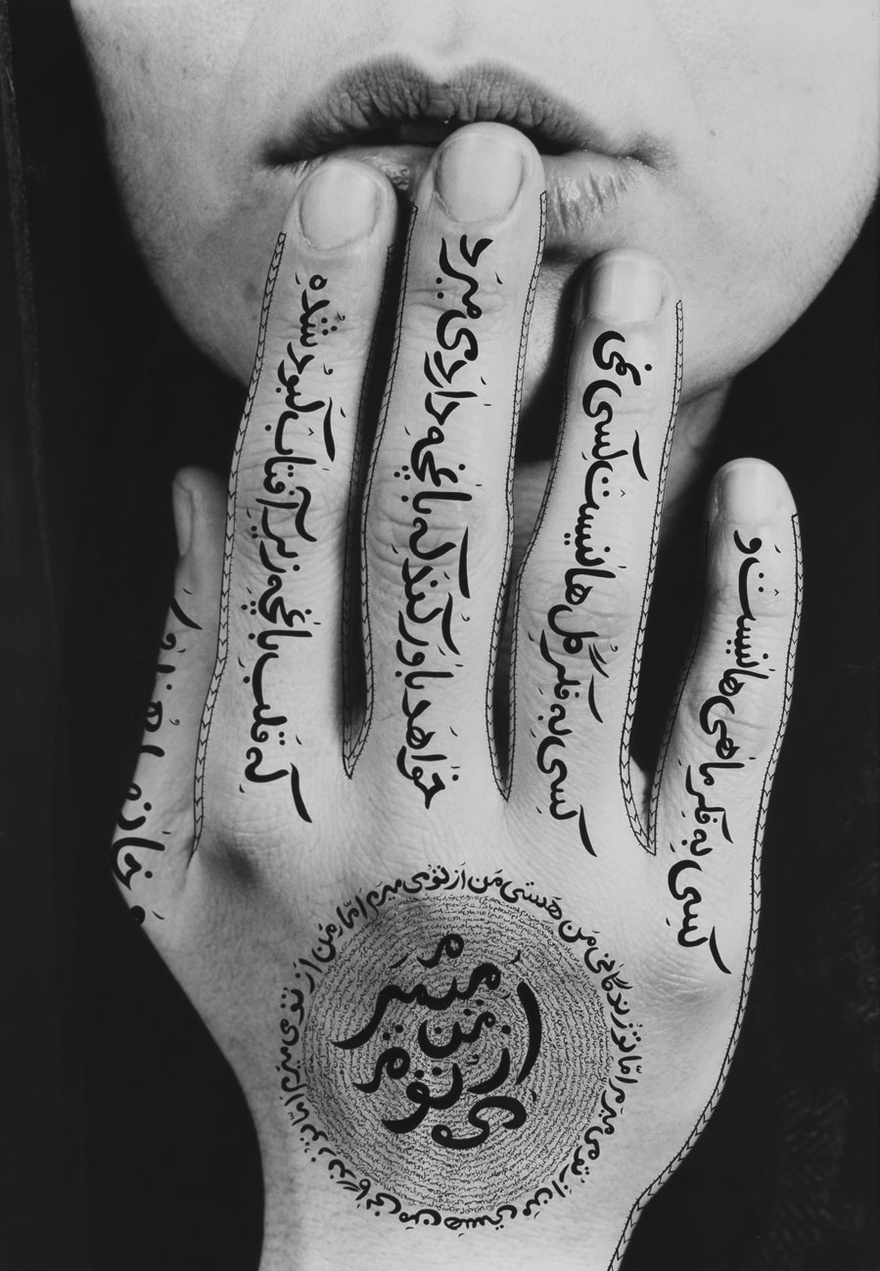

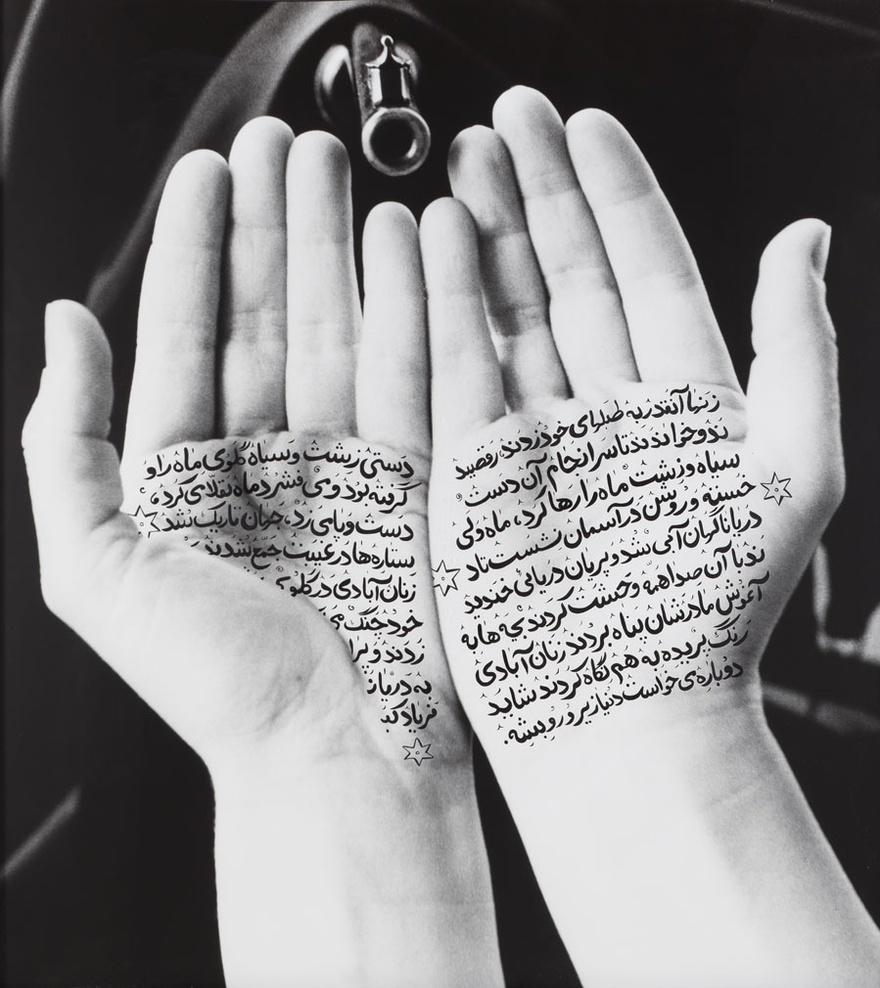

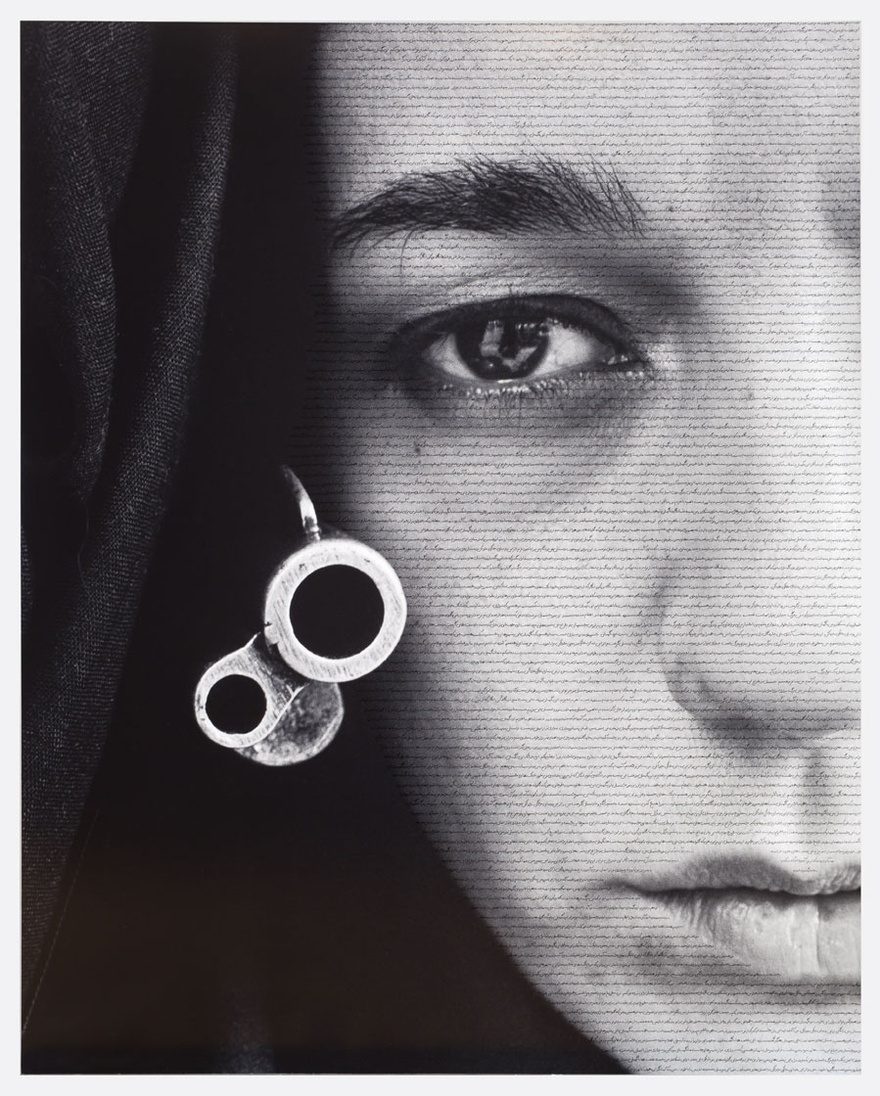

In 1993–97, I produced my first body of work, a series of stark black and white photographs entitled Women of Allah, conceptual narratives on the subject of female warriors during the Iranian Islamic Revolution of 1979. On each photograph, I inscribed calligraphic Farsi text on the female body (eyes, face, hands, feet, and chest); the text is poetry by contemporary Iranian women poets who had written on the subject of martyrdom and the role of women in the Revolution. As an artist, I took on the role of performer, posing for the photographs. These photographs became iconic portraits of willfully armed Muslim women. Yet every image, every women's submissive gaze, suggests a far more complex and paradoxical reality behind the surface.[7]

Neshat first exhibited the photographs in 1992 in a group show called Fever at Exit Art, the highly influential alternative art space in New York run by the artist Papo Colo and the curator Jeanette Ingberman. In this iteration, large-scale prints of several of Neshat's photographs were shown on pillars whose bases were submerged in piles of rocks. Fever was a survey of young artists, featuring more than 200 artworks by nearly 50 artists. The New York Times said the exhibit was marked by its 'scale, eclecticism and riskiness'.[8] Newsweek declared, 'If you see only one show this year, Fever should be it'.[9] Recounting the historic importance of Exit Art after it closed, a critic wrote in The Paris Review that Fever is 'often recognized as one of the decade's most provocative showcases of young American art'.[10]

In 1993, Neshat held her first ever solo exhibition, Unveiling, at New York's legendary Franklin Furnace. Founded by Martha Wilson, Franklin Furnace's mission has been 'to present, preserve, interpret, proselytize and advocate on behalf of avant-garde art, especially forms that may be vulnerable due to institutional neglect, their ephemeral nature, or politically unpopular content'.[11] The exhibition was staged as an installation, foreshadowing Neshat's subsequent mutli-media work. 'Unveiling explored the emotional and psychological state of living behind the veil for women in Islamic countries', Martha Wilson recalls. 'She did this by writing directly upon her body; projecting Super-8 film upon a bed of rocks; and referencing Islamic religious iconography.'[12]

The press release for the exhibition, issued on 22 March 1993, explained:

The fundamental question of what creates the female experience – the form or the body – confronts the viewer from a rare multi-cultural perspective. The problems of transposing Western presumptions of feministic artistic expression to another culture is also raised in this exhibition. References to Persian culture, Islamic religious icons and contemporary Iranian propaganda interact, creating surprising new meanings and challenging stereotypes about the female experience in Iran.

Early on, the bifurcated work of cultural translation was inscribed into Neshat's art, creating both an opening and dissonance in the works' reception.

A few months later, Neshat's photographs would be shown for the first time in museum exhibitions – group shows focused on immigrant art in New York and Los Angeles. Beyond the Borders: Art by Recent Immigrants opened in February 1994 at The Bronx Museum of the Arts. Neshat was featured prominently in a New York Times review of the show that highlighted the gendered politics of the photographs featuring veiling 'as a metaphor and a physical boundary'.[13] Still, Neshat questioned the overall thematics of the exhibition. 'Like others in the show,' reported The New York Times, 'Ms. Neshat said she was initially skittish about the entire concept of "immigrant art". The Bronx Museum curators themselves had long discussions about how to present the work without marginalizing it.'[14] In the summer of 1994, Neshat's photographs were included in Labyrinth of Exile at University of California, Los Angeles' Fowler Museum featuring four Iranian artists living and working in exile. 'The most striking ensemble here', wrote The LA Times critic William Wilson, 'is Shirin Neshat's Women of Allah'.[15] The curatorial framing of these shows was of the time, if a bit clumsy in emphasizing an artist's biography over the work itself.

If there was an inclination to bracket Neshat as 'an immigrant artist', there were other more generative and nuanced curatorial framings in which her work was presented. In autumn 1994, she was included in a groundbreaking exhibit at Exit Art that highlighted formal experimentation. …it's how you play the game was an evolving exhibit, an ongoing dialogue between Colo and Ingberman and three other curators – Thelma Golden (then at the Whitney Museum of American Art), Nancy Spector (then at the Guggenheim) and Robert Storr (then at Museum of Modern Art). According to Exit Art's archives, the show was:

A collaborative, conceptual exhibition project which investigated the curatorial process and revealed how curators' choices are reflective of their aesthetic and critical values… Curators took turns independently choosing and installing new works in response to the previous curators' selections. In this way, …it's how you play the game changed and expanded both physically and visually each week, reflecting and reinforcing a curatorial dialogue.[16]

In that context, Neshat was shown alongside artists like Kiki Smith, Cindy Sherman and Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Roberta Smith wrote in The New York Times that 'shows like these have perhaps been influenced by the grassroots activities of young artists and dealers who, released from the pressures of a high-powered art market, shall we say, have approached show time with an irreverent, improvisational self-consciousness'.[17]

By the mid-1990s, Neshat's photographs had clearly captured the curatorial imagination. In 1995, she was featured in a number of international biennials that were questioning the conventional boundaries of the art world. Curator Octavio Zaya included her work in the first Johannesburg Biennial. Zaya would again include Neshat in the 1997 Johannesburg Biennial, a section of which he co-curated with Okwui Enwezor. Francesco Bonami showed her work at the 1995 Venice Biennale. Stepping out of the shadows of marginalized 'immigrant art', Neshat was shown as part of the American Pavilion of the Istanbul Biennial in 1995 and then again in 1997. Curator Lynne Cooke included Neshat in the 1996 Sydney Biennale; in her curatorial statement, Cooke wrote about the curatorial voice: 'Rather than simply providing yet more information, curators do a great service by attempting to find issues, thematics and areas that provide a focus for their exhibitions'.[18] Neshat's rise in the art world through the 1990s paralleled the trend of growing curatorial authorship – one that challenged conventional exhibition norms, crossed geographic borders, and highlighted artistic experimentation with form.

Still commercial success seemed illusive to Neshat, who remembers the process of being rejected by numerous galleries as humiliating. It makes sense that her first New York gallery shows in 1995 and 1997 were with Annina Nosei, known for working with artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Robert Longo and Ghada Amer very early in their careers. In the small catalogue for the 1997 exhibit, Neshat wrote, 'My friendship and numerous collaborations with critic and curator, Octavio Zaya has been critical in the development of this work.'[19] Hamid Dabashi, a Columbia University professor, wrote an essay for the 1997 catalogue; he would become a major narrator of Neshat's artworks – writing essays, giving lectures, and engaging her intellectually throughout her career.[20] Neshat recalls that the first person to acquire one of her artworks from her shows at Annina Nosei Gallery was the artist Cindy Sherman.

Some critics, though, remained somewhat confused by Neshat's work. Reviewing her first show in a commercial gallery, The New York Times' Pepe Karmel wrote of Neshat's apparent 'nostalgia for fundamentalism' and came up with a pithy characterization of the work: 'Ms. Neshat's imagery seems tainted by a 1960s-style glorification of revolutionary violence: radical chic comes back, in her pictures as radical sheik.'[21] If Karmel's dismissal of the work seems rather cheeky, it signalled a persistent resistance to Neshat's photographs by some.

The Slovenian critic and curator Igor Zabel tackled this dissonance head on in his essay for the small brochure that accompanied Neshat's first solo museum exhibition held in the autumn of 1997 at Museum of Modern Art in Ljubljana, Slovenia. He wrote that Neshat:

Deals with generalizations, prejudices and stereotypes herself; she is, therefore, addressing the audience exactly on the point where their responses are already pre-formed, ready made. And exactly because she deals with these stereotypes, the effect of her works could be described as provocative; it necessarily implies uncertainty, perhaps even fear.[22]

This fear, Zabel suggested, derived from the ambiguity of Neshat's photographs, which seemed neither to be embracing nor condemning militant fundamentalism.[23]

Neshat didn't ignore the negative responses to her photographs. The work, she has told me, seemed too didactic, too rigid in its articulation of complex social and political themes. She turned to another medium – video installation – that allowed for more fluidity, nuance and complexity. Her first video installation, Turbulent (1998), also signalled another major turn in Neshat's artistic production – collaborative artistic endeavours. The filmmaker and artist Shoja Azari starred in the video, beginning a decades' long personal and professional relationship between him and Neshat. Ghasem Ebrahimian was the Director of Photography, and he would continue to work with Neshat on many subsequent projects. The inimitable Sussan Deyhim was the female performer, vocalist, and composer of the work – her music providing a beautifully haunting articulation of the gendered thematics that underpinned the piece.

Thelma Golden, who had been one of the curators of Exit Art's exhibition, …it's how you play the game, organized the first museum showing of Turbulent at the Whitney Museum of American Art's Philip Morris branch in the autumn of 1998. In The New York Times, Holland Cotter wrote that the installation 'is really about a wealth of male-female contrasts, suggested through body language, setting, camera work, and the music, which is thrilling'.[24] The critical reception of the piece seemed to suggest that the shift from photography to muti-media video installation represented a major breakthrough. 'Turbulent', wrote the critic Jerry Saltz, 'changes everything'.[25] In 1999, the Whitney would acquire Rapture, Neshat's next video installation. It would be the first major museum acquisition of the artist's work. That same year, Neshat won the Golden Lion at the 48th Venice Biennale for her video installations Turbulent and Rapture.[26]

In June 1999, Arthur Danto, the insightful and influential Columbia University professor and art critic, wrote in The Nation about visiting The Art Institute of Chicago. As they walked through a series of newly installed galleries, the curator James Rondeau introduced Danto to Neshat's video Rapture. Danto admitted to not having much liked Neshat's earlier photographs and so having missed Turbulent when it was on view in New York. But he was so taken with Rapture that he sat through the video three times. 'The situation of women under Islam is, one might say, the occasion of Rapture. But it rises to a universal level of humanistic allegory, making it significant for us all', he said. Neshat's new visual vocabulary had crossed borders, becoming more broadly intelligible and relevant. At the time, Danto had been contemplating what it meant to classify a contemporary work of art as a masterpiece. He added Neshat's Rapture to his own cannon of art works 'that qualify as masterpieces through the power of their vision'.[27]

This was Shirin Neshat's moment – not that night the auctioneer's hammer went down in Dubai. In 1999, her video installation had been called a contemporary masterpiece by one of the most respected art critics, it had won the top prize at Venice, and it had been acquired by a world class museum. The 1990s began with Neshat's jarring return to Iran that produced in her an urge to make art; a deeply complex and conflicted problematic that she sought to understand and represent through art. Her artistic journey took her through various formal articulations – staged photography, installations using film projection and found objects, and ultimately dual screen video and sound installations. Throughout this intense and complicated artistic process she developed and was buttressed through a creative community of critics, curators, scholars and fellow artists. Neshat's art was of the moment – irreverent and relevant. Of course, there is a significant market for Neshat's art, but ultimately it's not the market that sustains or propels her art.

During a visit to her studio in New York's Chinatown, Neshat reflected on her career. She told me:

Everything has happened so organically. I haven't tried to carve out a career. The only thing that keeps me relevant is that I keep challenging myself, working with new forms, reinventing myself. That's the artistic process: you embrace something new. It's about responding to this urgency that I feel inside. I feel like I'm always on the edge, always struggling. I don't really feel like a success – maybe that's because I keep taking risks, keep aiming for something more.

[1] Alanna Martinez, 'Will Iran's Art Market Go Nuclear?' The Observer, 21 July 2015, www.observer.com/2015/07/will-irans-art-market-go-nuclear.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Co-curated by Melissa Chui and Melissa Ho, Shirin Neshat: Facing History was on view from May to September 2015 at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C.

[4] 'Iranian art boom - 2006-2008,' artprice, 30 March 2009, www.artprice.com/artmarketinsight/469/Iranian+art+boom+-+2006-2008%253A+%2522progress+report%2522

[5] Indeed, Neshat's first ever mention in Artforum is in December 1992, in Andrew Ross' column 'Weather Report' on a colloquium she and Kyong Park organized on ecology and technology.

[vi] As quoted in: Robert Enright and Meeka Walsh, 'Every Frame A Photograph: Shirin Neshat in Conversation,' BorderCrossings, March 2009, www.bordercrossingsmag.com/article/every-frame-a-photograph-shirin-neshat-in-conversation

[7] Shirin Neshat, 'Artist Statement,' Signs, www.signsjournal.org/shirin-neshat

[8] Michael Kimmelman, 'Promising Start at a New Location,' The New York Times, 18 December 1992, www.nytimes.com/1992/12/18/arts/review-art-promising-start-at-a-new-location.html

[9] Peter Plagens, 'Summing up Doom and Gloom,' Newsweek, 24 January 1993, www.newsweek.com/summing-doom-and-gloom-192188

[10] Hua Hsu, 'Exit Art, 1982–2012,' The Paris Reivew, 12 April 2012, www.theparisreview.org/blog/2012/04/12/exit-art-1982-2012

[12] Martha Wilson, 'Staging the Self (Transformation, Invasions, and Pushing Boundaries),' in Performing Archives/Archives of Performance, ed. G. Borggreen and R. Gade (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2013), p. 340.

[13] Melinda Henneberger, 'Redefining "Immigrant" in the Bronx,' The New York Times, 20 February 1994.

[14] Ibid.

[15] William Wilson, 'Through the Lens of Iranian Culture: Two exhibitions at UCLA's Fowler Museum Enrich,' The LA Times, 2 July 1994, www.articles.latimes.com/1994-07-02/entertainment/ca-10931_1_ucla-fowler-museum-of-cultural

[17] Roberta Smith, 'The New, Irreverent Approach to Mounting Exhibitions,' The New York Times, 6 January 1995, www.nytimes.com/1995/01/06/arts/art-review-the-new-irreverent-approach-to-mounting-exhibitions.html?pagewanted=all

[19] Acknowledgments in the exhibition catalogue, Shirin Neshat (New York: Annina Nosei Gallery, 1997).

[20] Neshat's first ever mention in Artforum came in December 1992 in a column written by NYU professor Andrew Ross. Thanks to Lloyd Wise, Artforum's Associate Editor, for confirming this information.

[21] Pepe Karmel, 'Art in Review,' The New York Times, 20 October 1995, www.nytimes.com/1995/10/20/arts/art-in-review-075310.html

[22] Igor Zabel, 'Signs of a Divided World,' in Shirin Neshat, Exhibition Catalogue, (Ljubljana: Museum of Modern Art, 1997). Neshat also exhibited her photographs in 1997 at Vancouver's Artspeak, a non-profit artist run art centre.

[23] Over a decade later, Iftikhar Dadi would take up a similar argument in a more coherent manner, pointing out 'Neshat's work also refuses to choose between the subject positions supposedly available to the modern Muslim women – either traditional (subjugated) or Westernized (liberated) – and instead marks Muslim women's instability, untranslatability and incommensurability in the representational media strategies of the contemporary world.' See: Iftikhar Dadi, 'Shirin Neshat's Photographs as Postcolonial Allegories,' Signs (2008): p. 129.

[24] Holland Cotter, 'Art Guide,' The New York Times, 4 December 1988.

[25] Jerry Saltz, 'New Channels,' Village Voice, 8 January 1999.

[27] Arthur C. Danto, 'Pas de Deux, en Masse,' The Nation, 10 June 1999, www.thenation.com/article/pas-de-deux-en-masse