Essays

Absent Beirut

Reflections on Reflections

I.

During the summer of 2015, I visited Beirut in order to carry out a series of studio visits as part of a long-term research project on the representation of violence in contemporary art. As a result of this visit I have written a reflection based on three works that appear to have been issued from a common wound: the disappearance of Beirut, or one idea of it.

II.

Chafa Ghaddar's Spectrum (2012) was painted on the back wall of the Beirut Art Center for a 2012 group show titled Exposure. Abstract, and without vivid colour or clearly discernible form, the fresco stretched across three bays of the barely refurbished post-industrial exhibition space and was painted with earth tones (dull green, charcoal, ochre rust and tepid beige). Like a soiled sheet, the painting read like the map of a wounded space. The wall appeared to be bleeding rivulets of pigment. There were scars where plaster had been gouged out, seams between each giornata (the section of plaster painted in a day). Blossoms of black pigment – in their resemblance to toxic mould – suggested neglect, a building's slow death.

Fresco painting fell out of widespread use in the sixteenth century but for much of the Italian Renaissance it was the mark of an artistic talent confident of its formal mastery. The technique involves applying water-soluble pigments directly to fresh, wet plaster. This process has two important aesthetic implications, as summarized by Roman author and architect, Vitruvius:

The paints do not dissipate when they are carefully applied to moist plaster, but stay perpetually, because the lime, made weak and porous by having had its moisture baked out in the kiln, is forced by its emptiness to absorb anything with which it happens to come in contact. […] And so when plaster is made on walls as described earlier, it has got soundness, brilliance and durable quality.[1]

Fresco, in other words, does not create a surface. Plaster made of lime and sand particles is 'forced by its emptiness' to absorb pigment suspended in water, binding particles and pigment together through a chemical process. This process integrates vivid colour, in a narrative form, into the wall and then holds it there perpetually. This perpetual suspension is the technique's formal function.

According to art historian Péter Bokody, the shift towards fresco painting as the privileged medium for devotional murals in thirteenth-century Italy was due, in part, to its visual intensity.[2] In older techniques, such as encaustic painting, pigment is suspended in some form of wax and then applied to wood. The wax residue remains part of the colour, darkening it. Early encaustic painting is structured by a symbolic aesthetic language suited to its thick, flat, technical articulation. Fresco is weightless by comparison, as it involves no mediating binding agent. Pigment is suspended in water, which evaporates as the plaster dries. At the time of its introduction to widespread use, the technique's visual lightness allowed for a new range of figurative shading and thus for a much broader suggestion of both figural volume and movement. Bokody relates these technical developments to a shift in visual culture in the thirteenth century that saw volumetric realism gradually replace stiff, iconographic, medieval forms for representing the body. Fresco was developed, in other words, to materialize visual culture associated with Renaissance humanism, or with the representation of the human form as human rather than as an icon for some divine force.

Chafa Ghaddar travelled to Italy to learn fresco technique because she was fascinated both by the scale it allows vis-à-vis the body and the way fresco collapses the surface of a painting into the surface of a given space, i.e. the wall. Thus, Ghaddar extends a Renaissance humanist perspective on the relationship between representation and the body, creating abstract forms that the viewer nevertheless identifies with as a body. The relationship of fresco painting to the city, to its walls, is also crucial for an artist 'immersed in Beirut', as Spectrum illustrates quite lucidly:[3] the work is a painting of a dying wall made with a technique developed to suspend representation perpetually on the surface of a wall.

However sincere her apprenticeship in the medium, I would argue that Ghaddar has appropriated fresco in order to bend it against its own history. There was nothing light or human about Spectrum's careful representation of decay, nor did Ghaddar promise any permanence for the work – Spectrum was destroyed when the exhibition at the Beirut Art Center ended. Rather, her interest was in the indexical possibilities of the fresco itself and its ability to capture traces of the hand's movement and embed these traces in a building without any promise of survival. There is an important contradiction between the way Ghaddar makes her work and what the work pictures. Her depicted figure and ground are irreconcilable.

The mural was part of a larger project of the same name, Spectrum, which also includes a series of photographs of Ghaddar's family home in Beirut. The house was damaged by fire in 1985, leaving a section uninhabitable, and thus was abandoned to slow decay as moisture seeped through a lapsed roof and mould crept across the walls. Art historian Sintia Issa describes Spectrum as an attempt to stop time or as some kind of representational tourniquet to the wound inflicted on the home.[4] I was drawn to Issa's analysis because it echoes a widespread belief that if catastrophic or unjust events are simply made visible they will stop happening. Our awareness of the wound, materialized in an artwork or a photograph, will cauterize it. But what aspects of home or of childhood memory does Ghaddar's mural seek to fix and suspend on a wall? How does she stop time when the ruins she pictures in the photographs and figures in the mural were wrought by a persistent lack of resources or attention, or a combination of the two, over decades? What is the wound that killed the home?

Perhaps what Ghaddar highlights with Spectrum is an awareness of how wounds are not events that occur in any singular sense; wounds are never finite, they do not end even when they heal. Wounds expose us to physical and psychic vulnerability in the moment of their inscription on bodies and minds, but they only become truly poisonous over time. Wounds left untended threaten the integrity of our homes and in doing so they also threaten the architecture of our memory. Ghaddar's work does still decay over time, which illustrates an ecosystem of violence rather than a desire to stop the process by which a home dies, as Issa suggests.

III.

Ibrahim does not want to witness the disappearance of Ramallah. The sense of being so close to disaster is intolerable. He wants to return to Beirut right now, tonight. It would take four hours to drive, without traffic. His lover is anxious; he wants to understand Ibrahim's disturbance. 'Did any of my friends bother you? Did I bother you?' he asks. 'No, no' – Ibrahim just wants to leave. The dialogue ends after Youssef acquiesces to return to the hotel to collect their few belongings and drive directly to Beirut from there.

The camera tracks away from the car the two men are driving in and moves across Ramallah at night, panning quickly over darkened apartment buildings and glowing convenience store fronts. Street lamps, the headlights of cars moving in the opposite direction, decorative strings of coloured bulbs framing what looks like a used car lot; all of this light glistens off the pavement, soaked by night rain, as more lights shimmer in the distance.

'Youssef.' Ibrahim speaks his lover's name quietly after the emotion of the previous exchange. 'You have been here more than once. Have you ever felt that Ramallah is disappearing?'

'Disappearing?'

'Yes.'

'I don't get it.'

'It's nothing. Never mind.'

There is another long pause, before Ibrahim says, 'I love you.' Thickly. An expression of the pressure the city endures and that these two men endure as a result of their existence in it, even if momentarily. (Just a weekend getaway.) Youssef responds, 'I love you too.' The camera continues to track a bustling roadside at night, after the rain, but the two men are silent.

In an interview with Phillip Schmidt in 2014, the director of this love story set on the road from Ramallah to Beirut, Roy Dib, says he thinks of his film Mondial 2010 (2014) as an oblique portrait in the vein of Alain Resnais' classic Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959).[5] Resnais' movie, for Dib, is about making a picture of a city after a disaster or in the middle of one. In both works, characters suffer from what seems to be a delusion; a waking dream about where they are and when. Both movies picture a delayed response to some event that is never fully acknowledged, perhaps an event never fully understood by its participants. Both represent a collapse between memory and the city, in which the urban landscape is enough to trigger a traumatic recollection. This collapse and this trigger is the substance of the urban portrait in both cases.

Ibrahim, as a Lebanese man, could never see Ramallah himself in reality. As articulated in the notes for the film:

The relations between Israelis and Lebanese are governed by the 1943 Lebanese Criminal Code and the 1955 Lebanese Anti-Israeli Boycott Law, the former of which forbids any interaction with nationals of enemy states, and the latter of which specifies Israelis, making a trip for a Lebanese citizen to Israel (or Palestinian territories) impossible.

Thus, in a literal sense, Ibrahim does not possess the ability to see or experience Ramallah disappear. This political fact would need no explanation to a Lebanese audience. Since 1955, no vacationer has been able to casually drive the four-hour distance between Beirut and Ramallah for the weekend, which is the narrative premise of Dib's film; the very same reason Dib could never go to Ramallah to shoot this particular work himself. This is the delusion (or an impossible history) at the heart of the project. Dib produced the work using footage sent to him by non-Lebanese nationals visiting Ramallah as part of a much larger project soliciting amateur videos of various cities from friends and strangers. He edited many hours of rushes and then wrote a script to accompany his edit, which is read by actors and dubbed as an additional layer of sound to that of the original footage.

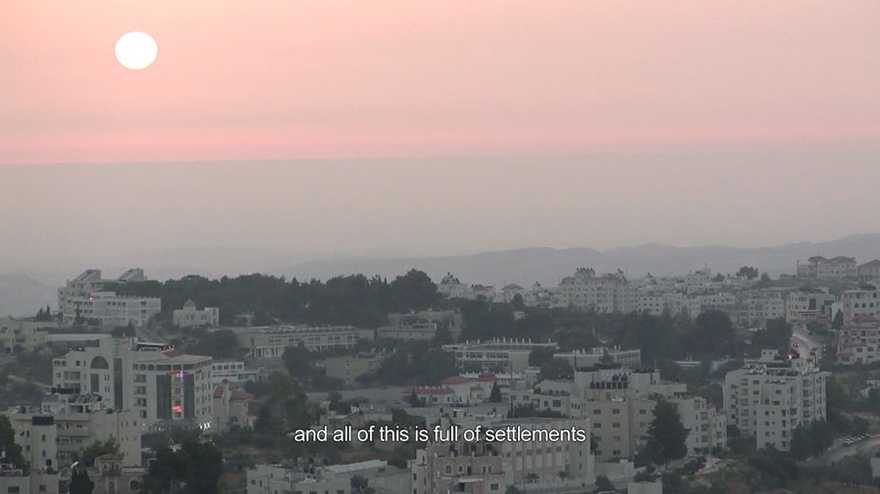

In the interview, Dib responds to the question of disappearance in light of this political context: Lebanon and Israel are at war. There is no civilian relationship possible between the two countries. Partly as a consequence, he was raised to support the rights of Palestinians to return to their land. Dib's intention – as well as that of the people who took the original footage – is to represent the encroachment of Israeli settlements on Ramallah within proximity to tourist hotspots, from the bar and the hotel that Ibrahim and Youssef visit during their stay.

The refusal to acknowledge a right, a person, or an argument is to wish for the disappearance of the very thing under dismissal. One way to think of Ibrahim is as a figure that becomes possessed by the impossible history of the Palestinian people, embodied as it is by the very fact of the Palestinian's existence within the occupied territories despite the persistent, lethal fantasy imposed upon them by the Israeli state that they and their cities would just disappear.

Ibrahim can leave Ramallah with his lover, just as he can refuse to witness its disappearance. But Ramallah's vulnerability remains intolerable to him – produces a delusion in him – because he is haunted by another, displaced, disappearance inscribed into the history of Beirut's own extreme historical defencelessness in the face of Israeli military action. In this sense, their entire journey is a delusion, the function of which is to return Ibrahim to an event he survived, yet is unable to bear witness to. That is, the disappearance – or its reappearance, post-war, in unrecognizable form – of Beirut.

One way to understand Ibrahim's predicament is through literary scholar Cathy Caruth's conception of trauma, which is defined as an experience too violent to be integrated safely into a person's subjective narrative at the time of its occurrence. The parameters of experiences considered 'too violent' are individual; they depend entirely on the subject and cannot be universalized. But traumatic memory can nevertheless be characterized by the experience of being returned, in dreams or in waking life, to the scene of one's trauma. Flashbacks, delusional episodes, traumatizing dreams, and fits of rage in response to casual conversation about topics seemingly unrelated, all intrude in a literal sense on a subject's otherwise rational everyday life. 'The traumatized', Caruth writes, 'carry an impossible history within them, or they become themselves the symptom of a history that they cannot entirely possess'.[6]

There is also another way to understand Ibrahim's confusion. Psychoanalyst Dori Laub defines trauma as an event that destroys its own witnesses. In other words: a person must experience, on some level, the emotional reality of the event they are witness to. If they do not, they cannot testify to its experience. Writing about the Holocaust, Laub argues that:

History was taking place with no witness: it was also the very circumstance of being inside the event that made unthinkable the very notion that a witness could exist. […] The historical imperative to bear witness could essentially not be met during the actual occurrence.[7]

The Holocaust is a catastrophic event that constitutively exceeds understanding. No analogy can be made between it and any other violent conflict. That said, Laub's insight into the structure of trauma might be useful in contextualizing a video about two cities, Ramallah and Beirut, that have been threatened, and by some accounts disfigured, by military operations on the part of the Israeli State.

In Mondial 2010, the portrait of one city is thus inextricably linked to the portrait of another, just as the disappearance of one is similarly linked to the other. To imagine a car ride to Ramallah that is innocent enough that the travellers in the car might argue over forgetting a book, or about how many beds to ask for in a shared hotel room, is to dream not only of the transgression of international sanction. The film is also a wish for a memory (and a city) that remains intact and uninterrupted by the absences that trauma so often produces.

IV.

The first photograph of a series titled The Reeds (2013), which Beirut-based visual artist Lara Tabet made in collaboration with Michelle Daher, is a night shot of reeds giving way to inchoate blackness or a void. The image has no depth and no figure. The last photograph in the same series is almost entirely out of focus with a woman shown at the centre of the shot turning away from the camera. Thick interlocking layers of foliage do not frame her but rather form the space in which she appears. She is like a hole in the centre of the photograph into which the image drains. Tabet's opening and closing scenes encapsulate the project: a series photographed in a part of Beirut called Dalieh, the Arabic word for a hanging plant ubiquitous on Beiruti rooftops and terrace gardens. The site has been in use continuously for 7,000 years and its diving cliffs and open-access beaches are emblematic of Beirut's relationship with the sea. The area has also been home to a longstanding fishing community, important marine fauna ecosystems, and precious green space for festivals and other celebratory gatherings in a city with less than a square metre of green space per resident.[8]

Since the time of Ottoman rule, Dalieh had been owned by several local families and was governed by clear municipal restrictions to safeguard the coastline from private development. In the mid-1990s, three companies associated with former prime minister Rafik Hariri purchased parcels of land that, combined, comprised of the entire area. On the basis of a law passed (some say illegally) in 1989, during the Lebanese Civil War's chaotic twilight, development plans began to take shape that would block free access to the site. During the summer of 2014, barbed wire was set up to make this point concretely.[9] The development plans provoked immediate and widespread protest both locally and internationally; an open letter written by The Civil Campaign to Preserve the Dalieh of Beirut was sent to the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, whose office OMA is in charge of the building project,[10] and Dalieh was put on a watch list by the World Monuments Fund.

On a panel called 'Resilient Urban Waterfronts', organized by the American University of Beirut in February 2015, Amira Solh, senior urban planner for Solidere, the massive umbrella company responsible for much of Beirut's beach front development since the end of the Civil War, argued that 'there is a price to having a private company take on Beirut City Center [Solidere's flagship development in Beirut]. And that price is that you rely on a private company to also ensure the public good.'[11] Part of what reliance means in this context, according to Solh, is a re-education of the city's inhabitants. 'I think public space is a process of learned citizenship', she argued in relation to the massive re-development of Beirut's former Green Line zone by her company. 'Public space is something we are getting used to again. […] I encourage everyone that doesn't go downtown, go walk it, it's time for us to reclaim the city centre.'[12]

For artist Tony Chakar, this understanding of citizenship is anathema to the city's history and Solidere's recourse to it in the context of privately owned urban zones is a fantasy meant to reassure the afternoon lounger that there is no secret here, no open wound. His pre-emptive rebuttal to this wish, published in the spring of 2014, argues that the development only extends the city's disappearance: 'after the war the destruction of everything around us did not stop, it just took on other forms and acquired other names, like "reconstruction", or the "building frenzy", or simply "economic growth" and "tourism."'[13]

Tabet also sees development as a 'polishing of the city', or its 'destruction by annihilation then shiny replacement'[14] – a shiny replacement that is not witness to the city's wound in any complex sense.[15] 'What is the landscape's reality and that which is imposed by its function?' Tabet asks. Put differently: Can the city be reduced to some use value determined by global capital? And if not, what else is it? The Reeds is a portrait of Dalieh at night, when it becomes one of Beirut's few (illicit) public cruising zones. Instead of a nostalgic longing for something indelibly absent, Tabet asks how the space might be altered – partially, contingently – through some use of it that contradicts Solidere's programmatic vision. This use is not addressed to history, nor to any concrete wish for the future. It is not an act of witnessing but rather an intimate refusal to believe in Solh's version of citizenship. It is an act of belief, perhaps, that there is a secret city to which anyone could claim some right.

Tabet also describes the project as an 'oneiric exploration of one of the rare public spaces' in Beirut, where dreaming is understood, in the Freudian sense, as a wish issued from the subconscious. We dream what we do not give ourselves permission to ask for. If these are photographs issued from a city that is dreaming, then what does the logic of the dream depend on? And what is the secret, which is not the same as the wound, that Tabet wishes to disclose with her images of figures whose contours emerge indistinctly from the space around them?

Cruising, for queer theorist Michael Warner, is about world-making. A dream of public sex is a wish for some social existence beyond what heteronormativity allows. 'What one relishes in loving strangers is not mere anonymity, nor meaningless release. It is the pleasure of belonging to a sexual world', Warner argues.[16] The 'publicness' of public sex is defined by a need to recognize and be recognized by others as 'a public' rather than as a pair of bodies in private. The pleasure it offers is one 'in which one's sexuality finds an answering resonance not just in one other, but in a world of others in a way that one sustained intimacy cannot',[17] for many of the same reasons that the 'publicness' of political protest is pleasurable – to be one in a sea of people who see the injustice, to be recognized as a political subject, and to recognize one's solidarity with others is to experience a (momentary) lack of political alienation.

Warner, however, may reject this analogy to political protest, a more recognizable form of marginal or transgressive publicness than sex, certainly. Pleasure in publicness as a form of world-making is compromised, according to Warner, by its proximity to patriarchal forms of power and modes of address:

This pleasure, a direct cathexis of the publicness of sexual culture, is by and large unavailable in dominant culture, simply because heterosexual belonging is already mediated by nearly every institution of culture. Publicness can have little of the sense of accomplishment or world making so long as its putative wildness is compromised by the banality of normal heterosexuality, or so long as its distinctively male way of occupying public space remains a way of dominating women.[18]

There is a transgressive form of pleasure that is specific to queer sex in public, then, or to its capacity to open the subject to something inside herself that she does not yet know: the stranger. (This is also the object of dreams, in the Freudian paradigm.) The object of this kind of sex is to produce recognition for the subject beyond all other available forms of recognition. It is an act of belief in a subject's need to dream themselves.

But, if the photographs ask 'what is absent in the city?' and one answer is 'the world that queer public sex makes', then what do the photographs actually depict? Tabet and Daher went to a park where they took photographs of men and also of themselves. Yet we should think of these images not as photographs in an indexical sense, testifying to some event that took place at such-and-such a time and place. They are photographic memories of the desire for recognition – specifically for recognition of a feminine version of the world built by men cruising – rather than the record of sex in public as performance. 'Perhaps through transgression', Tabet writes, it might be possible to reconnect with Beirut, a city she describes as 'disfigured' and 'hostile'. The transgression, for Tabet, is not only the act of cruising but also the act of picturing it. Again, she is not witnessing the city's disfiguration as some transparent mark of the stable past. She uses the camera as a 'tool of transgression and seduction' that allows for 'the reversal of power/gender roles' in a particular case.[19]

What is at stake in such a fleeting and specific transgression? I would suggest that political alienation is in part the result of a psychological violence that damages the ability of subjects to dream and to wish. Tony Chakar articulates this danger in bleak terms:

I look around me and I see land utterly destroyed by past, present and future wars, a dreamscape of ruins all around, from Lebanon to Palestine to Syria to Iraq; I listen to people and discover, astonished, that concepts like laws, states, citizens and so on mean absolutely nothing; that they are aware of the fact that this land – their land and mine – is destroyed, like one is aware of being in a nightmare, and so they internalize their parts and act them out.[20]

I do not wish to soften this insight, but I do point away from it in order to look towards the ghostly forms Tabet captures in her series of photographs. These images offer the viewer access to another kind of dream, a gendered dream in defiance of heteronormativity and its latent brutality.

V.

Wounds are fascinating in that they are physical traces of violence that have become signs, which thus renders them visible. Wounds are like objects issued from a missing present. They are indexical to violence, yet they cannot coherently describe the moment, the event, the day, or the years of an event's passage. Like photographs, their meaning is both absolutely factual and utterly at the mercy of the reader. Thus, if a wound is by its nature irreducible to objective qualification, the three works discussed in this essay are particularly effective in picturing how wounds are intransigently subjective. The recourse the artworks presented here have to subjectivity is due to the knowledge that the event is both endless and absent, and that the body must somehow hold this contradiction.[21]

[1] Vitruvius, Ten Books on Architecture, trans. Ingrid D. Rowland (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1999), pp. 89-90; Cited by Péter Bokody in Péter Bokody, 'Mural Painting as Medium: Technique, Representation and Liturgy,' in Kép És Kereszténység: Vizuális Médiumok a Középkorban [Image and Christianity: Visual Media in the Middle Ages] (Pannonhalma: Pannonhalmi Főapátság, 2014).

[2] Péter Bokody in Péter Bokody, 'Mural Painting as Medium: Technique, Representation and Liturgy,' in Kép És Kereszténység: Vizuális Médiumok a Középkorban [Image and Christianity: Visual Media in the Middle Ages] (Pannonhalma: Pannonhalmi Főapátság, 2014).

[4] Sintia Issa, 'Prestigious art prizes awarded to three Lebanese women,' The Daily Star, 17 November 2014, see: http://www.dailystar.com.lb/Arts-and-Ent/Culture/2014/Nov-17/277838-prestigious-art-prizes-awarded-to-three-lebanese-women.ashx

[5] Roy Dib and Phillip Schmidt, 'Interview Roy Dib "Mondial 2010"', https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xe7nuZJR6Jg.

[6] Cathy Caruth, 'Introduction,' in Trauma: Explorations in Memory (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), p. 5.

[7] Dori Laub, 'Truth and Testimony: The Process and the Struggle,' cited in Caruth, op cit., p. 7.

[8] 'Dalieh of Raouche,' World Monuments Fund, https://www.wmf.org/project/dalieh-raouche.

[9] Habib Battah, 'A city without a shore: Rem Koolhaas, Dalieh and the paving of Beirut's coast,' The Guardian, 17 March 2015,

http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/mar/17/rem-koolhaas-dalieh-beirut-shore-coast.

[10] The Civil Campaign to Preserve the Dalieh of Beirut, 'Open Letter to Mr. Rem Koolhaas,' Jadaliyya, 15 December 2014, http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/20264/open-letter-to-mr.-rem-koolhaas.

[11] Amira Solh, quoted in Habib Battah, op cit.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Tony Chakar, 'To Speak Shadow,' Afterall 25 (2014): p. 23. See: http://www.afterall.org/journal/issue.35/to-speak-shadow.

[14] Lara Tabet, personal email message to the author, 14 March 2016.

[15] I am responding here to Tony Chakar's view on 'how to respond to the city's destruction'. Chakar writes: 'How, then, to speak it [the past]? The problem with most witnessing is that sometimes, even without knowing it, it presupposes a direct relationship with the past; it assumes that the past is transparent; that the present, which is destroying that very past every single second, has no bearing on it; that it is enough to speak it "as it was" and everything will be whole again. But this will not happen: what has been broken can never be mended.' Chakar, op cit., p. 24.

[16] Michael Warner, 'Zoning Out Sex,' in The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life (New York: Free Press, 1999), p. 179.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] All quotes are from: Lara Tabet, personal email message to the author, 14 March 2016.

[20] Chakar, op cit., p. 21.

[21] The author wishes to thank Chafa Ghaddar, Roy Dib and Lara Tabet; the participants of Public Sculpture at The Cooper Union during the autumn term of 2015; Jared McCormick and George Awde of Marra Tein in Beirut, without whose support for the initial research, this text would not have been possible; Orit Gat; and Randa Mirza.