Essays

Informal Domains

Art and Culture Beyond Institutions in Amman

Over the last decade, the arts and culture scene in Amman has been growing considerably. Although cultural production is not yet on par with a capital city of three million inhabitants of complex political histories, nor is the city a 'sexy' destination for international curators or cultural producers, Amman has been contributing a hefty calendar of cultural events in recent years.

National institutions like the Royal Cultural Centre and the Hussein Cultural Centre are budgeted for and staffed by the government and the Greater Amman Municipality respectively. They are centrally located – standing in grand architectural unison – and play receiving hosts to large festivals such as the annual Contemporary Dance Festival and the Human Rights Film Festival, as well as to local and international theatre productions. The Royal Film Commission, also funded by the government, has steadily worked on supporting local filmmakers and cultivating a local film audience.

Private endowment institutions have established themselves in the realm of cultural events; Darat al-Funun, for example, has initiated international contemporary art exhibitions while steadily supporting local artists. Independent galleries have been dotting the city's artistic map with photo, print and illustration exhibitions. Al-Balad Theatre, one of only a handful of independently run theatres in Amman, regularly puts on performances and festivals for alternative music, contemporary theatre, and the burgeoning genre of storytelling.

Naturally, this growth raises questions regarding the relationship, relevance, and accessibility of these institutions with regard to the Ammani public. As anywhere else in the art world, the institutional constituents of this cultural landscape face controversy year after year. Many of the middle-class and working-poor see art and culture as a privilege of the few, and perhaps rightly so.

One prominent example to illustrate this feeling is the Jordan Festival, produced by the organization 'Friends of Jordan Festivals', which was established in 2010 to 'Implement His Majesty King Abdullah's vision, in promoting Jordan as a touristic, cultural and economic destination',[1] as their mission statement affirms. The festival was held over two hot summers at the Citadel of Amman, the ancient capital of Rabbath-Ammon and a hugely significant site in the city, home to ancient Ummayyad, Byzantine and Roman ruins as well as the underrated Jordan Archaeological Museum. The Citadel tops Jabal Al-Qalaa, one of the seven hills that elevate modern day Amman, and is a diverse working class neighbourhood.

Prior to the festival's launch, local authorities fenced off the area of the Citadel and designated it as tourist-friendly, adding entrance fees and placing signage on the public artefacts. The local community complained that they had lost their public space, and the authorities eventually allowed the community to enter the Citadel free of charge. On the other hand, the festival – showcasing large-scale international music performances – was accused of disturbing the peace (music performances would last well into the late night hours) by the local community, as well as of being elitist (some ticket prices for single performances were in amounts the residents of the neighbourhood, if not most of the city's inhabitants, could not afford).

In light of the above, it is no surprise that institutions – be they large or small – still find it challenging to attract diverse and regular audiences beyond the usual art crowd. Audience building has been a sticking point in the agendas of cultural institutions and many organizations have enacted hefty outreach efforts to expand their arts audiences. This is particularly true of the European national centres, like the French Cultural Centre and the British Council. The recently formed European Union National Institutes for Culture coalition compiled the many art and culture spaces of Jabal Al-Weibdeh onto a single map that is now installed on many of the neighbourhood's street corners. To launch the map, they initiated a series of guided walks for the general public and brought in targeted groups like school children in large numbers to explore the area. But are audience numbers enough of a measurement? And what of the quality of the artist products in the programmes and projects presented above? Few in this city seem to question or assess the social relevance of their artistic programming, let alone the long-term socio-emotional impact.

On the other end of the spectrum, Amman has also seen a rise in smaller, artist-run collective spaces and projects, bringing a more radical and grass roots practice to the city sphere. These informal art structures – which can be defined by traits of fluidity and un-affiliation – offer alternative avenues for arts production and dissemination that are capable of fulfilling unmet communal needs and addressing issues of social and political importance. It is this rise of informal art structures in the context of Amman that is the focus of this essay, as well as the conditions they are reacting to and how these alternative frameworks are put into practice.

Makan Art Space, established in 2003, has been at the forefront of this movement and has worked hard to create a much-needed space for artistic experimentation in the capital. Initiated in 2003 by a group of four curators and artists, Makan has lately been inviting social initiatives and guest curators to make use of the space as guests see fit, most recently with ArtTerritories from Palestine. Another notable Makan project was the Shatana International Artists' Workshop, a summer residency that took place in a sleepy northern Jordanian village away from the buzz of the city.

It could be said that Makan paved the way for other alternative spaces such as The Studio, Jadal, Mohtaraf Al-Rimal, and Meme to enter the local cultural radar. However, some of these spaces do not have solid or clear programming due to lack of experience and resources, and often fall into the trap of trying to do too much. Yet, many of these independent, temporal projects have succeeded in breaking the traditional rhythm characteristic of institutional arts-structures and programming in Jordan.

One noticeable example is Hamzet Wasel, a culture and community initiative that takes the previously mentioned neighbourhood of Jabal Qalaa' as its locale. They have forged very close relationships with the residents by running creative programmes for the children of the area and addressing community needs through constant dialogue to preserve the social and cultural heritage. They also act as liaison for other initiatives that want to intervene there, facilitating an environment of direct urban relevance.

Ta3leeleh, another non-traditional initiative, hosts an open-mic platform for young creatives from diverse backgrounds to share ideas. They travel between different spaces in the city, and have recently expanded their realm to the northern city of Salt and the southern poverty pocket of Ghor al-Mazra'a. Throughout the years, they have developed a sustainable model for rotating leadership between the initiators of the project and volunteer members. The latter are responsible for key roles in running the programme, many of who initially joined Ta3leeleh as young speakers or performers in music, poetry, or dance.

In this way, Makan, Hamzet Wasel, and Ta3leeleh represent a defining characteristic of informal art strategies in Amman: they are working to address needs unmet by larger cultural institutions by responding to the city, its artists and its residents in ways that formal institutions (governmental, social or arts organizations and museums) cannot.

Yet, despite their differences, there also exists substantial overlap and collaboration between formal and informal arts actors in the city, and the need for collaboration is by no means surprising. Resources are limited in this wavering city where contemporary arts and culture are still on the periphery and this modest reality has resulted in a supportive arts community. Smaller groups and larger institutions come together, whether to take advantage of the committed audiences of each and thus stretching the reach of their projects, or by supporting one another technically and logistically.

On the other hand, intersections of overlap and collaboration can also cause friction and dissonance as smaller institutions and informal structures are often unable to deal with the bureaucracy and nepotism that plague Jordanian governmental bodies. Performances in public spaces, film festivals and many other activities require permits from local authorities that are sped up through personal connections and the influence of large institutions. In March 2014, the Audio-Visual Commission approached several small spaces in Amman that hold regular pirate film screenings and prohibited them from continuing such programmes. Larger institutions that hold such screenings without purchasing film rights were not targeted in this shameful campaign. Small spaces, including Makan and Jadal, are now in dialogue to overcome these restrictions.

Perhaps, then, we can look at the intersections of collaboration, overlap and dissonance as dichotomizing spaces that help to articulate characteristics critical to the success of informality and un-affiliation. How do the contrasts presented above help us define what it means to be 'informal', and furthermore, what are the benefits of this informality?

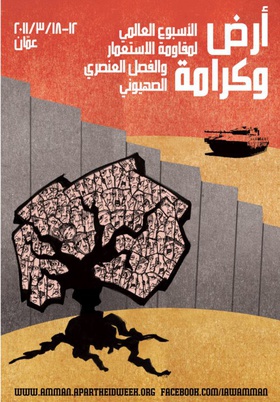

I will present some examples of projects that I have been involved in, in the hope of offering a personal reading on these thoughts and questions. In 2011 and together with nine other individuals, we set up Ard wa Karama, a collective organizing for Israeli Apartheid Week in Amman. For two years, we put on an annual programme of lectures and discussions, film screenings and concerts to shine light on the oppressive practices of the Israeli occupation of Palestine. We invited activists, historians, politicians and artists from Jordan, Palestine and South Africa to share their experiences and stories with audiences in various locations around the city. We were informal political and social activists, but were able to bring visibility to prevailing but under-represented issues in Jordanian society: the boycott of Israeli goods and normalization as an example. The initiative did not continue past the two years, but some of its members later formed an offshoot committee that works specifically to tackle boycott issues in Jordan that is still active till today.

In this case, working informally was a naturally political process – we put ourselves in a public position, treading the political sphere, but we had the freedom to create a different set of politics outside of the system. We did not belong to a political party or an institution, and we were using the arts at the core of our programme. We had to map the current structures and managed to carve our own space among them.

Another critical trait of collectives and independent structures is non-hierarchy and fluidity. Creating horizontal platforms allows for the sharing of goals, ownership and knowledge while maintaining safe spaces for difference and even (or especially) failure. Straddling across the landscape of the meagre River Jordan, The River Has Two Banks is a multi-disciplinary platform initiated with Shuruq Harb and Samah Hijawi in 2012 that pushes for the idea of physical mobility between not only Amman and Ramallah, but also for the traveling of history, social practice and common political struggles between the entirety of Jordan and Palestine. We use mobility as resistance and this notion has allowed us to connect with disparate groups of people from artists and curators to scientists and environmental activists.

This focus on commonality has created a bidirectional sense of ownership whereby participants have a sense of ownership over the project as much as the organizers do. The project invites artists from Jordan and Palestine to travel to the 'other side' to present and discuss their work. As such, political border realities have been an immense challenge for us; we have not been able to accommodate the travel of many Jordanians to Palestine due the complications of obtaining permits (we do not endorse the use of the Israeli visa). However, we are working with several other groups in Jordan and Palestine that are invested in this idea of commonality and exchange to try and find collective solutions for this problem and in the hope of creating a trans-national civic network pushing for and supporting mobility.

This year, I am working with Noura al-Khasawneh on The Spring Sessions, a communal learning and arts residency programme for artists and cultural practitioners in Amman. The underlying principle of the pilot edition is to 'unlearn' existing ways of seeing in order to create new perspectives and push the boundaries of creative production. We have accepted around 20 participants in the programme that runs for three months, inviting regional and international artists to conduct workshops and develop works in the space in collaboration with the participants. In a city where there is little besides outdated formal and academic education in arts, The Spring Sessions aim to create a community where these young artists learn by practice and discussion.

In our search for a space for the project, we stumbled upon the King Ghazi hotel, a previously derelict and abandoned old hotel in the center of the city. It is a prime location; the hotel is housed on the second floor of a twentieth century building, the street level of which is now occupied by bustling vendors and juice shops. We have renovated it to cater to working spaces, a small library, kitchen and film screenings on the roof. Our independence and non-affiliation as a collective has allowed us to place ourselves in a different context from the onset. We are working in a domain unusual to the current picture of the art scene in Amman today, activating an unused space with great potential in the heart of the city.

It would be amiss not to mention that the freedom we enjoy at The Spring Sessions – a freedom critical to our capacity to create, share and grow – is derived partly from the nature of our funding. Having secured entirely local funding from individuals and private companies, the group is not bound by the constraints and/or politics of international or government monies.

The Spring Sessions is an attempt at creating a community of artists, conscious of the importance of carving an independent space, a physical and metaphysical one, thus creating its own personal, collective and creative affiliations. As with many of the initiatives discussed here, we are mindful that the odds for our sustainability are not always in our favour, and realize the challenges in remaining fluid and untenured financially and of expanding our practice beyond the usual audiences. But in this setting, as transient guests in the hotel of downtown, we are as much in dialogue with the street vendor below us and hassled daily by the authorities from above, as we are amongst each other, creating new works and drawing new narratives for and in the city.

Many thanks to Garrett Rubin, Rheim Alkadhi, Noura Al-Khasawneh and Shuruq Harb.