Interviews

The State of a Nation

Larissa Sansour in conversation with Sheyma Buali

Larissa Sansour's work, mainly in the form of video art but also photography, installation, graphic novels and other media, has shifted a great deal from the beginning of her practice. Her short films answer to the Palestinian question and often incorporate themes surrounding food, humour and, increasingly lately, science fiction and visions of the future. Constantly renewing her modes of discussion, the ultimate effect desired through her work is ways to redefine long-discussed issues to do with Palestine, political negotiations, ideas on belonging and a Palestinian statehood. Here, Ibraaz Editorial Correspondent Sheyma Buali speaks to Sansour about the role of historical knowledge in her future visions as well as the incorporation of Zionist myth, identity as objects and the void of the present.

Sheyma Buali: Nation Estate (2012) references historical points within a futuristic landscape. There is signage of historical spots, cities and landmarks throughout. Clearly, your work is informed by reality and current situations and debates. But what kind of role does history take in your work?

Larissa Sansour: It's very much informed by history: I take the present political situation on the ground, with the history of Palestine as a reference to what I am working on. So even though it seems that what I am doing is surreal, this parallel imagined universe that I create is firmly based on the political situation in Palestine. This suggested or posited new world is an attempt for me to re-address the same Palestinian issues but in a different context. What you see in Nation Estate is a skyscraper. The idea comes from the need for a viable Palestinian state. The fact is that if you go to Palestine now, you'll see that there is hardly any space left for such a state, and you would have a hard time seeing how a state is even possible. I come from Bethlehem. Today, the city is completely surrounded by settlements, and every time I go there they are moving closer and closer, slowly eating up the land that a Palestinian state was supposed to be established on.

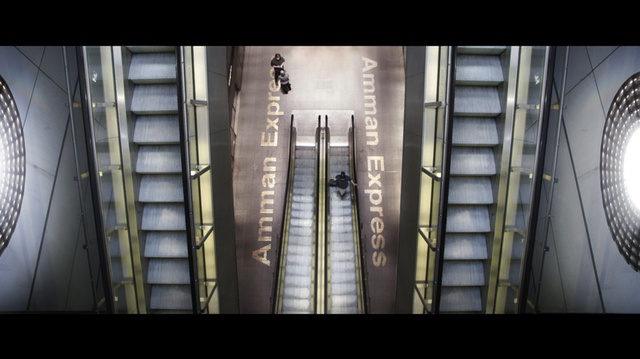

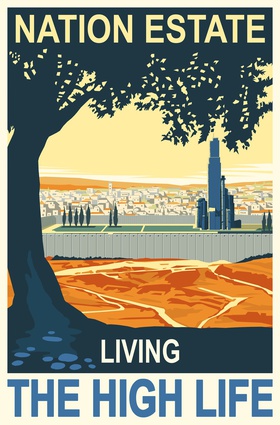

The fact that there is hardly any space left makes me think that the only way we can make a space for Palestine is vertically – upwards like a skyscraper – rather than horizontally. Obviously, Nation Estate is an ironic take on the problem at hand and the illegal confiscation of Palestinian land by the Israeli state, with each city having its own floor: Jerusalem on the third floor, Bethlehem on the fourth floor, and so on. But many of the problems that Palestinians are going through are accentuated in the film where you see that elevators have replaced roads and checkpoints, for example. In this, traveling to Palestine through Amman, Jordan, which is the only way Palestinians can travel into Palestine now, would become much easier. A trip that usually keeps Palestinians stranded for eight hours or more on the Jordanian border, where they are subject to humiliating questioning and searches, can in the future projected in Nation Estate, be done in 15 minutes by the Amman Express. The film features a big billboard that says 'Nation Estate: Living the High Life'. It is high-tech, and it is a skyscraper. But of course, all these added comforts of living only accentuate the dystopian reality of this building or of any such solution to the statehood issue.

SB: There are also visual references to traditional iconography, like the keffiyeh and the key, which are now associated with ideas of resistance and the right of return.

LS: I try to use these as though they are objects in a museum. It's a comment on identity politics; somehow when you are in the midst of such a long struggle, your identity and things usually associated with it lose their value as they become cliché. I wanted to make the Nation Estate building like a museum that houses these symbols we are supposed to identify with; and because they are in this museum, they are not functional. They become exhibited artefacts. This included references to the keffiyeh and the key that we all know, plus certain foods like the olive trees. The embroidery on my pockets was actually embroidered by women in Bethlehem.

Again, I'm trying to find a different medium by which we tell the narrative. It's interesting how values shift when symbols are put in a different context. I like seeing the Palestinian flag, for example, in a context that you don't associate with Palestine, like in Space Exodus (2008), where we have a context like landing on the moon, which you associate with progress and futurism. There, you look at the flag on the sleeve of the astronaut suit and all of a sudden the flag starts to look different. I like the shifts that contexts produce for things you've always seen.

SB: So in a way, it is a world where solutions are met, things are progressing, but they are dismal; like the dark, cynically hi-tech futures of science fiction.

LS: I like this tension between utopia and dystopia. I think it is kind of universal. I try to have this play between locality and universal concerns. It is interesting for me how the post-apocalyptic condition that Palestinians are going through is actually something that we are all worried about. The only thing is that what is happening to Palestine is coming to us before its time, because of political reasons rather than environmental reasons. My work borrows from sci-fi, which deals a lot with the post-apocalyptic condition: what do we do in the future? Obviously this is all informed by what is happening in the present. How do we deal with this condition? What is it going to look like in the future?

It feels to me that what is happening in Palestine is like a microcosm of world problems in general. I find it strange when I realize that people don't think that what is happening there is central to world problems. But to me it is the source of so many global challenges. A lot of tension in the world could be traced to the Middle East and how power there has been aligned. It is also about the continuation of colonization in other forms and it is one of those places where the colonization law is still valid for some reason and that makes what is happening there acceptable to the so called 'international community', when it wouldn't be acceptable somewhere else.

SB: Other than the blur between utopia and dystopia, humour finds its way into your visions. This used to be more blatant with works like Bandolero (2005), Happy Days (2006) and Sbara (2008); but now the humour has become somewhat darker. In Nation Estate, you are commenting on the grave situation of land encroachment. Lawrie Shabibi's text on your work describes it as a 'playful dystopia'.[1] In Space Exodus, apart from the reference to a classic movie, there is something liberating about the idea of being able to go to space and start a new world, until we realize the astronaut has been pushed to space, where she falls into a deep, openness, losing contact with Jerusalem for what might be forever.

LS: What can be seen as humour is, I suppose, the sense of hopefulness in the work. In Nation Estate the humour is much more subdued and satirical, whereas in Space Exodus it is a bit more in your face. The blurriness between utopia and dystopia is something that fascinates me. There is of course an element of optimism in seizing power in your own hands, taking control of your destiny, self-determination and a pure demonstration of human will, albeit in a fictional context. Still, a feeling of impotence permeates the work, but I think it is an impotence that not only covers that of the state of Palestinian affairs, but of humanity's inability as a whole to come to come to terms with its own advancement and progress when it comes to human rights or technology. It can throw you off balance because you are talking about something grim and dystopian, then all of a sudden you also have some hope. It has a lot to do with the fact that I am very interested in the interplay between reality and fiction. I am fascinated by how much of reality ends up mimicking fiction, rather than the other way around.

Nation Estate has a lot to do with early Zionist mythology. For example, the poster 'Nation Estate, Living the High Life', is based on a well-known and recognizable Zionist poster from 1936 that originally states: 'Visit Palestine'. It is interesting to me how much mythology played a role in the early years of Zionism, and I like Jean-Luc Godard's take on this, where he says: 'Jews become the stuff of fiction; the Palestinians, a documentary.' The infamous saying, 'A land without a people for a people without a land' was the greatest myth. But actions on the ground mimicked this myth and Israel continued over many years to shove Palestinians off the land and replace their villages and farmlands with illegal settlements for Israelis only. If Israel is ever forced to evacuate and remove these settlements, then Israel for sure would recreate this event as an Israeli tragedy.

For me, Nation Estate follows the strategy of building undeniable facts on the ground, no matter how surreal. What I like about the use of sci-fi is that it always brings back the past and the future, but it never talks about the present. It seems that, as Palestinians, we have built an identity of being eternally suspended in space or stuck in limbo: we think about the Naqba, the tragedy and what happened, and we look for independence in the future. But meanwhile, on the ground, Israel is busy expanding its settlements on Palestinian land and amplifying its reality.

SB: Speaking of that, you mention the quote of 'Land without a people and a people without a land' and then there are the many utterances of 'they do not exist', starting with Golda Meir. This utterance took on a life of its own. We see responses to this, from the first militant films such as the one actually titled They Do Not Exist by Mustafa Abu Ali (1974), as well as many documentation practices, up to Hamid Dabashi's description of the entire oeuvre of Palestinian cinema being a 'cinema of visibility'. So this kind of constant need to prove that Palestine and Palestinians existed and exists is ongoing. How does that fall on you as a Palestinian filmmaker? How have these utterances affected you?

LS: I think if you were born and raised there you would understand the obsession with this, because things disappear. For example, areas that were available to me as a kid, I can't access anymore, or things get destroyed. The cityscape has completely changed. And that is normal under occupation; that is what happens. I think there is an obsession with Palestinians to just document things. When I first started to work with video and photography, I chose it because it was not a painting, you can't question it: it was documented on tape.

SB: Yes, that is true. One of your earlier works that drew me to you as an artist was Land Confiscation Order 06/24/T (2007), which dealt with the idea of place and memory. The film features your brother and sister finding an old home that they are restricted from. It was very much based on geography and land, being there and having that moment. Your more recent work goes into the idea of land and nation(ality) but in outer space, becoming much more abstract. Can you talk about your path, and how you went from one mode of thinking – looking at the past and the story of the physical geography – to the next: an imagination of a somewhat nonexistent, non-physical future?

LS: Land Confiscation Order 06/24/T is an autobiographical short video that I made in 2006. My family received a letter from the Israeli state, saying that my family's land and house would be confiscated by the state of Israel because the government was building a settler-only road that would need to run through the land and therefore eat up the areas around it. I found the matter of fact-ness of this document not only shocking, but also the way in which it was delivered to us very disturbing. The letter was pinned under a stone on the land itself, not sent to our postbox. This is a systematic tactic that Israel uses when communicating with Palestinians.

Through images of childhood memories of the place and the fear of what it would look like in the future, the strategies of domination and terror of occupation are addressed in a slow, dreamlike state. Land Confiscation Order 06/24/T is a requiem for a land that was owned by many generations of my family, but that we might never see again. This state of displacement and statelessness continues in my more surreal and fictional recent work, with A Space Exodus for example. In the film, I play the role of the first Palestinian in space trying to establish a connection with Jerusalem, but failing. The work again addresses the question of a viable Palestinian state and looks for the moon as the ultimate refuge for a people that have been denied the most fundamental of human rights.

SB: The post-Naqba narrative is now three generations old. A lot of the ideologies, the ideas of nationalism and home, have become somewhat outdated. As an artist, how do certain pasts inspire new ideas for the future?

LS: I think artists and filmmakers from my generation operate a bit differently than the previous ones. We have grown accustomed to documentaries from and about Palestine and the Palestinian people, and it seems that a new strategy is needed because audiences worldwide have become immune to information coming out of the region. People are tired of the news that comes out of Palestine and think of it as repetitive and beyond solvable. After all, the problem at hand has been going on for more than 60 years, so it is understandable that there is a general fatigue on the topic. The tragedy is that, due to all this, Palestine has lost its human face.

SB: Your next project, though, is pretty innovative. You will be challenging both museums' roles as well as certain points that you spoke about here surrounding myth and artefacts related to Palestine. You once described it as an 'investigation of archaeology and how digs can determine cultural DNAs'…[2]

LS: In the absence of any real peace process, archaeology has become the latest battleground for settling land disputes. Unearthed history is used as an argument for rightful ownership of land. My new project is a performative counter-measure to the unearthing of artefacts in order to justify further confiscation of Palestinian lands and erasure of Palestinian heritage. 200–300 pieces of elaborate porcelain – suggested to belong to a future nation of hi-tech, highly sophisticated, yet entirely fictional Palestinians – are buried deep into the ground in the West Bank, for future archaeologists to excavate. Once unearthed, possibly hundreds of years from now, this tableware will provide physical evidence supporting the myth of this historically hi-tech people, thus justifying future Palestinian claims to their land.

The project stretches the very idea of fiction beyond its natural boundaries by not just fabricating a myth of a future hi-tech nation, but rather physically constructing evidence for this myth as informed by real events, hence providing the tools for the myth to present itself essentially as a non-fiction. The work itself becomes a historical and narrative intervention - de facto creating a nation.

SB: But what if Israeli military dig them up first?

LS: I guess you'll have to stay tuned.

Read Sheyma Buali's essay for Platform 007, in which she discusses the work of Larissa Sansour amongst others, here.

Larissa Sansour was born in Jerusalem, and studied Fine Art in Copenhagen, London and New York. Her work is interdisciplinary, immersed in the current political dialogue and utilizes video, photography, installation, the book form and the Internet. Sansour's work has featured in the biennials of Istanbul, Busan and Liverpool. She has exhibited at venues such as Tate Modern, London; Brooklyn Museum, NYC; Centre Pompidou, Paris; LOOP, Seoul; Queen Sofia Museum, Madrid; Louisiana Museum of Contemporary Art, Denmark; House of World Cultures, Berlin and MOCA, Hiroshima. Recent solo shows include Anne de Villepoix in Paris, Photographic Center in Copenhagen, Sabrina Amrani in Madrid, Kulturhuset in Stockholm and DEPO in Istanbul. Shows in 2013 included her solo show at Lawrie Shabibi in Dubai, the MuCEM in Marseille, the Bluecoat in Liverpool, Harlem Studio Museum in New York, White Box in New York and the Turku Art Museum in Finland. Scheduled shows for 2014 include FACT in Liverpool, Reverse in Williamsburg, NYC, and Wolverhampton Art Gallery. Larissa is represented by Anne de Villepoix in Paris, Lawrie Shabibi in Dubai and Sabrina Amrani in Madrid. She lives and works in London and Copenhagen.

[1] 'Science Faction,' Larissa Sansour solo exhibition, Lawrie Shabibi Gallery, Dubai. 9 September–13 November 2013 http://www.lawrieshabibi.com/exhibitions/30/overview/.

[2] 'A Re-Imagined Palestine: Haniya Rae interviews Larissa Sansour,' Guernica Magazine, 16 September 2013 http://www.guernicamag.com/art/a-re-imagined-palestine/.