Interviews

Flash Futures

Monira Al Qadiri in conversation with Stephanie Bailey

Monira Al Qadiri is concerned with reality and how it exposes itself in events that occur seemingly out of nowhere, like flashes of insight. What unites her body of work is the sustained investigation into how institutionalized culture manifests in both macro and micro ways – projects interrogate major events, from the collapse of the informal Kuwaiti stock market known as the Souk al-Manakh in 1982, to the burning of the Kuwaiti oil fields in 1991 as the first Gulf War came to an end when Saddam Hussein retreated back to Iraq. Yet, aside from historical frames, Al Qadiri's concerns are also cultural, ideological and metaphysical – identity and role-play are common components in projects that also explore subjective positions within a wider context, such as how one might mediate the structures of belief that shape collective identities. In this interview, Qadiri explains how economy, conflict, power and metaphysical values play a role not only in the configuration of cultural institutions within the Gulf, but also in the configurations of culture in general.

Stephanie Bailey: I wanted to start with a discussion around a work you produced in 2012 for Creative Time: Rumours of Affluence, which takes as its starting point the collapse of the informal market known as the Souk al-Manakh in 1982. The Souk al-Manakh was set up as a separate trading ground to the main Kuwait Stock Exchange, fuelled by higher oil revenues that had resulted from the oil crisis of 1979, and precipitated by the Iranian Revolution and greater restrictions on the main stock exchange caused by a small crash in 1977. By the early 1980s, Souk al-Manakh became the third largest market in the world: a market on which people could trade in shares of foreign companies, and for which many Kuwaitis borrowed from banks. You trace a link from the bursting of the Souk al-Manakh's bubble, to the dissolution of Kuwait's parliament in 2012, then the third dissolution in less than a year and a result of a bribery scandal dubbed the 'Kuwaiti Watergate'. Can you talk about what prompted you to make this video work?

Monira Al Qadiri: What I was trying to convey in this video most of all was that like any national tradition or cultural trait, corruption can also have a cultural legacy of its own. Emulating a sort of indigenous 'art form', it has its own history, heritage and cultural legacy that affects much of what is happening today in the region. But it is mostly undocumented and unwritten, and the only way we can have access to the 'archives' of this culture is through fleeting rumours about those times after decades have passed. Nepotism, gambling, excess, decadence, and power relations are all part of this thriving 'culture', and I chose the Souk al-Manakh crash as the moment these phenomena were at their peak. We are the inheritors of this tradition, so I just wanted to trace where it started.

SB: And in terms of being an 'inheritor' of this tradition – this thriving 'culture' – how would you define or describe it and how do you think this relates to your practice as an artist?

MAQ: I think by simply living here we all consciously or unconsciously participate in the culture of corruption – entire nations are founded on it – and we both benefit and suffer from it. The art world is also not immune to corruption, so I wanted to imagine and visualize its inner workings as a starting point for a discussion.

SB: Rumours of Affluence alludes to a kind of collapse – the implosion of a framework or infrastructure that led to a certain disintegration. From this, I wanted to bring into the discussion Behind the Sun (2013), which, like Rumours of Affluence, takes a single event as it's starting point: the burning of the oil fields in Kuwait, which took place in 1991 after the first Gulf War, when Saddam Hussein's invading force left the country. Can you talk about how these two works might relate to one another within the context of Kuwait and its recent history?

MAQ: The initial idea I had for Behind the Sun was to explore my biographical relationship with oil – petrol – in its most basic material form, and how that first encounter transformed my perception of my country's economy as well as my own identity as a Kuwaiti. Until that point, oil was an invisible material to me, just a wealth-producing mysterious magic potion of sorts. It was only when the oil fields were burnt after the war that we actually saw it for the first time. This idea ties in with Rumours of Affluence in that we base our lives on illusions surrounding wealth and sources of limitless income and growth, when these things are inherently finite and fragile. When their materiality is exposed, when one realizes these things are not quite so magical and transcendent, that this is just black liquid burning in the ground, their mythical status implodes. Maybe these works are a reflection on what 'economy' means on the whole.

SB: The idea of 'economy' and what this means – how would you reflect on this notion? I am thinking about the economy as both a local and global phenomenon, as articulated in Rumours of Affluence, given the Souk al-Manakh was predominately used to trade in foreign markets. I also wonder how this fits into your experience of the burning of the oil fields in 1991 as a kind of wipe out? This notion of the economy, after all, is arguably what prompted the very burning of those oil fields, in many ways, no?

MAQ: Yes, the burning of the oil wells was a symbolic act of destruction that basically entailed burning money in real-time over a period of several months. As I said before, the mythical status of oil dissipated as its vulnerability was exposed, changing people's perceptions about economic stability and 'nationhood' entirely. The concept of Kuwait as a state with a solid economic premise (oil) suddenly migrated into a temporary void. 'Kuwait' itself transformed into a temporary project. In a similar way, when global markets reach crisis point (as in the stock market crash of 1982), the vulnerability and instability of capitalist economic systems is also exposed. In my imagination, the global economy has a metaphysical quality to it, because it is so complex and difficult to comprehend. But when it crashes, illusions of great wealth fade, leaving only crystal-clear images of chaotic human greed in their wake.

But all too often these flash moments of clarity – the burning wells, the stock market crashes – are quickly forgotten and replaced with façades of stability. This is maybe one of the reasons I like to look back at them.

SB: In Behind the Sun, you combined amateur VHS video footage of burning oil fields with audio monologues from Islamic television programmes of the same period, which were very much informed by tropes of religious representation geared towards visualizing God through nature and expressed in Arabic poetry. There is an apocalyptic treatment to the images of the burning fields when listening to the orator express, in a deep voice, lines like: 'the night is erased by the day, whenever you wish, and if you will it,' as smoke and fire literally ignite a dark sky. Can you talk about why you chose to combine a real event with the narrative of dramatic, religious poetry?

MAQ: The impulse was to try to open up an event that is only ever seen under a political or historical gaze onto another plane. Werner Herzog had already done this before me with his docu-fiction film Lessons of Darkness (1992), in which he filmed the burning oil fields from a helicopter – a god-like perspective from above – and combined a narration of Christian biblical texts on the apocalypse with a Wagner soundtrack. When I was young (and obviously didn't know who Herzog was) I had hated this film for twisting the facts and superimposing a fictional narrative on top of something real that I had just experienced. It took me many years to appreciate this technique of looking at reality differently. I guess what I attempted to do in this film was to create my version of this concept, and to fill in the gaps that were out of tune with what I had personally faced. In other words, not to have detached overhead shots from a helicopter, but amateur video taken from the ground looking directly at the fire, and also to emphasize the cultural and religious context in which this event was taking place.

SB: From this I wanted to bring up one of your latest works, produced in 2014, Muhawwil (Transformer) – a four-channel video installation based on Islamic figurative murals from electric power stations in Kuwait. According to your statement on the work: 'These murals mark a transformation in religious discourse within Gulf societies: where once only calligraphic depictions of this nature were allowed, today's pop-culture and mass-production of images have forced conservative entities to reconsider this tradition and take up a mutated technique to convey moral advice - wall paintings.' Thus, you reconstruct these wall paintings into animations 'so as to highlight the dilemma of representation that exists between the ancient and the modern.' \

Firstly, I wanted to talk about how this work relates to the themes of Behind the Sun and Rumours of Affluence – there seems to be commonalities in the sense that you have taken two ideas – systems of religious representation and networks of energy and power – and overlapped them. This makes me think of your approach to religion as one that has infrastructural concerns and leads me to ask: are you are producing layered cartographies of society's construction so as to visualize its contradictions? If so, why and how?

MAQ: Yes, in Muhawwil contradictory and paradoxical ideas are highlighted, and this is, as you say, an exercise in visualizing how these opposing elements are rationalized alongside one another. But what I'm trying to do with these works is not a criticism per se, but rather a reflection, or a process of augmentation. In Muhawwil, I did not imagine nor make up the bizarre murals portrayed – they exist everywhere in the city and I made sure to keep them as true to what they are as much as possible – but by animating them I essentially 'augmented' this already existing reality.

SB: There is a sci-fi element to Transformer that comes out of the installation, which is presented as a cuboid structure that recalls the form of Mecca, upon which animations are played out on screen. This raises ideas around the object of projection, which, if I am to be honest, reminds me of the building in Philip K. Dick's Maze of Death, in which a group of people experiencing a simulated situation on a foreign planet trying to discover their purpose there, all see a building with a sign, yet they each read this sign differently. Did you have such thoughts in mind? Of ideology and belief systems as collective projections that are at once singular yet totally fragmented?

MAQ: I was nervous when I first exhibited the work, as I was sure that at least someone in the audience would interpret it negatively. But surprisingly the reactions I received were so varied and personal that it is exactly as you described – they each read the signs differently. This made the piece much stronger as I was not imposing my own narrative, nor could I control the outcome. Perhaps this is how religion and other belief systems (economic systems included) function as well. They generate multiple interpretations and applications, which is what gives them their power.

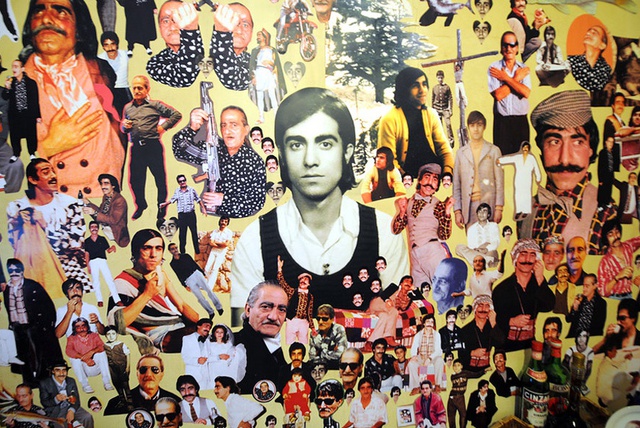

SB: I wonder how this corresponds with the notion of identity in your practice. I am thinking about your projects The Tragedy of Self (2009-2012) and Anachronistic Fantastic (2013). Could you talk about the thinking behind these works?

MAQ: These works primarily deal with notions of individualistic narcissism, and the performativity of masculinity. In the late-twentieth century especially, developed societies were (and still are to a degree) excessively focused on individualism as the ideal space within which one performs the functions of a successful human being. So much so that it became some kind of sacred space. This is not a natural consequence of modern life in my opinion, but a view that is systematically imposed from the top, and one that serves to create non-communal, non-altruistic people. So yes, there is an element of power play here, as well as the connection between worship and celebrity. Additionally, as a child growing up during the Gulf war (1990-91), I felt that men were doing all the fighting and that women were stuck at home being afraid. This created a strange link between masculinity and narcissism in my brain, and I have been obsessed with images of masculinity ever since. I perform it in my works myself – I use it visually, sonically, and conceptually. It stems from a personal past. This is also an idea I put forward in Behind the Sun by using the overly dramatic masculine 'holy voice' as a backdrop.

SB: This idea of a personal past relates to the project you have produced for Ibraaz, which conflates the burning of the oil fields with the building of cultural institutions that took place in the Gulf in the 1990s and beyond…could you talk about this new work and how you have overlapped these two historical moments, one being a flash in the pan, and another a sustained project of cultural development?

MAQ: Recently I heard an interesting lecture by Dr. Alexandre Kazerouni in Kuwait about his theory on the evolution of modern-day mega museums in the Gulf, and how the war in Kuwait contributed to that transformation. A seven month – as you say – 'flash in the pan' conflict dispelled many myths about the foundation and strength of the Gulf as a whole, so the new museums basically started as a PR exercise directed at western audiences – in essence towards their new subjects. This concept intrigued me immensely. I am an artist from Kuwait, and these are the museums I imagine seeing my work in someday. It was a shock to hear how 'our war' was the trigger that shaped the current artistic landscape of the region. For me personally, so many elements collided with each other upon picturing this idea. I feel there is a lot of truth in it. People are always asking the question why is the Gulf investing so much in art institutions in recent years, perhaps this can be one accurate explanation. And again, economy, conflict, power and metaphysical values play a role in this configuration.

See Al Qadiri's project MYTH BUSTERS, produced especially for Platform 007, here.

Monira Al Qadiri is a Kuwaiti artist born in Dakar, Senegal, in 1983. Having lived through the 1990-91 Gulf War, she became fascinated by Japanese animation as a means of escaping the harsh realities she experienced. At the age of 16, she moved to Tokyo on an art scholarship from Kuwait's government. In 2005, she completed her first animated film, Visual Violence. Since then, she has been conducting research into the relationship between psychology and art, and on the aesthetics of sadness in the Middle East. In 2010, she received her PhD in intermedia art from Tokyo University of the Arts. Her work has been shown in group exhibitions and film festivals in the USA, Russia, Germany, the UAE, China and Japan. Al Qadiri is also a member of the GCC collective.