Interviews

From Central Asia to the Caucasus

Leeza Ahmady in conversation with Taus Makhacheva

In this encounter, curator Leeza Ahmady and artist Taus Makhacheva unearth subtle links in their respective practices and in between the regions they navigate, or dismantle. Taking the form of an online 'studio visit', the discussion below took place over a period of eight weeks. What emerged was an ambitious and wide-reaching conversation that took in a range of topics, from Russian wedding banquets, to body builders and male wrestlers, to the history of object-making in the Caucasus.

Taus Makhacheva: I would like to begin our conversation by sharing a 'welcome' videoso you might get a sense of the space I work in. I made this for a panel discussion at Courtauld Institute of Art to coincide with the exhibition, Close and Far: Russian Photography Now (2014) at Calvert 22.

Leeza Ahmady: Thanks! The notion of one's city as a studio space in its own right is often spoken about, and creating this very literal video of yourself welcoming viewers to your favourite spots is a brilliant way to drive this point home, although this was not exactly your intention. Strangely and wonderfully, it makes your absence very present.

Ultimately however, beyond a physical realm, the quintessential space for creativity is within one's being. While physical spaces are instrumental, I am interested in studying those kinds of spaces intuited within oneself from which spring forth both conceptual forte and aesthetic integrity. The physical manifestations of these hermetic spaces are what I call 'process' or the artwork. Can you recall a moment in your life when something clicked for you in that you wanted to make art? Did the discovery of that space, which I call 'the internal studio', come about consciously? Or did your art making start by accident?

TM: I wanted to be a clown when I was a child. My first degree was in economics. So I was heading in a different direction.

There is another wonderful story about how I did not want to become an artist. My mother is an art historian and writes about contemporary art from time to time, so I was often taken along to various art events and museums to the point where, in my teens, I refused to enter any art-related institutions. I think I was in middle school when I went with my mother to a performance at the A3 Gallery in Moscow called Zikr by Ibragim Supyaniv, which was performed by Apandi Magomedov, Murad Kazhlaev and Oleg Pirbudagov – a performance that explored a religious, traditional mourning. I was asked by a visitor if I wanted to be an artist. I clearly remember the line of thought running in my head:

No definite working hours,

No clear evaluation,

No salary,

No structure,

Never!

At the time, it all read as a nightmare. Now, it all reads as the happiest finding.

I think there was a moment when I realized I did not want to be a photographer. It was during a shoot for Afisha magazine (the Moscow version of TimeOut) about ten years ago. I could not find a connection with the subject of the shoot and decided that if I could afford it, I would never again take part in a project I was not interested in conceptually, nor would I deal with people who I did not find interesting to work with, or something along those lines. So I guess it was a rather ego-driven decision about desire to control my output and the situations I was in.

'NO' became really important; I often start thinking about things and works, formulating how I don't want it to be done, how I don't want it to look. When I make work, in my head it goes through multiple rings of 'NO'. So when I got into Goldsmiths, my experience was driven by my desire not to be confined within photography and dependence on someone else's vision of the outcome. During my interview, Simon Bedwell asked me questions that made me realize Goldsmiths was the place I wanted to go. And I still remember a metaphor that Sam Fisher (head of the BA program at the time) used. He said: 'we make you walk on the wire while you are on the ground and then slowly lift it up.' So you go up without even noticing. I think he mentioned it in my final year, when I accidentally looked down. I owe so much to all the wonderful people who taught me there.

Regarding spaces, you are right when you talk about my treating an entire city as my studio. I have never really used a physical studio space, never felt the need, exactly because of the inner studio or what you call 'the internal studio'. I have to admit, that this space has formed unconsciously: I could not make myself sketch/play with materials/put postcards on the walls and so on. Although I am still making attempts to create a physical space with a massive luminous sign that reads 'Taus Makhacheva's Studio', now I only see it as a well structured storage space, but not the space of production. The inner studio is the only space where my outer studio's collections get processed. I started the project for Ibraaz's 008 platform, for example, by flipping through the latest editions of Dagestani wedding magazines.[1] The bridal style-mixtures in these publications form the same gap between the two shops in Makhachkala city, which I addressed in the welcome video. So that inner studio within me therefore, acted as a kind of shredder for the magazines, and the output was to create my own collection of wedding photography by crash-attending 19 such celebrations in one day.

LA: Some artists claim that their works have nothing to do with them personally. I am interested in whether anyone can truly leave their personality out of their art. After all, the personality (ego) is perhaps the most stubborn of characteristics in human beings. What do you think?

TM: In a straightforward manner, I like to reformulate this question to address how I choose to use myself in my art works. Sometimes, I wish there was less of me, in some works it makes no difference, and many times I end up using myself as a choice that's most economical: my resources are always free of charge. There are works where my body and my ego are very present, but hopefully not self-indulgent. I often find works about privacy and artists' personalities interesting, but I believe I tend to take a different approach. I am a right-brainer and communicate through images much better than with text.

In the works where I am present, it is justified by a larger context and inquiry that is never only about my experience or 'inner world'. I am often questioned about how natural my choice of subject matter is.

The thing I am thinking about right now is music. Some music makes your blood boil, some you ignore – I guess it is the same for me with choosing areas of inquiry in the region I am from and where I am living now. I use myself as a catalyst, perhaps, or as the object of the work, to talk about disengagement in current wedding culture, for example, as was the case with my 19 a Day project for Platform 008, for which I collaborated with Makhachkala-based wedding photographer, Shamil Gadzhidadaev. On 14 September, we tried to visit as many weddings as we could, and 19 was the final number. There are more than 60 wedding halls in the city. Late spring, summer and early autumn is peak season for weddings, every weekend all the halls are in use. For the project, I crashed random weddings, pretending to be an invited guest. I congratulated the newlyweds, danced, ate, and took stereotypical shots guided by the expertise of Shamil's professional knowledge. We intended to document the possible mimicry of a wedding-crasher, bridal styles, be it a bride in a western-style dress with a hijab, or elaborate crowns – I wonder, what region do you see when you just look at these images?

LA: Yes, weddings are a central event in people's lives all over the world. Indeed the dress, customs, décor, and so many other elements in your images can be placed anywhere from Greece to Mexico, to Tajikistan. The images also provoke a wonder about the stories behind these seemingly festive scenes, as weddings are universal symbols for class, status, wealth and prosperity. For that matter, in some parts of the world, especially in Asia, people get into astronomical debt to keep up with wedding cultures. In 2011, for example, the Afghan government tried passing a law to prevent banks from giving loans to families financing weddings, and posed restrictions on the growing Wedding Halls phenomena, where incredibly lavish 1,000 to 3,000 guest parties cost average Afghans (mainly the bridegroom and his family) tens of thousands of dollars. An expensive wedding has become the right of passage for young men to demonstrate their masculinity. Interestingly, you explore attributes of masculinity in your works perhaps more primarily than, let us say, femininity. What experiences in your life would you say have influenced your choices in subject matter, medium, style?

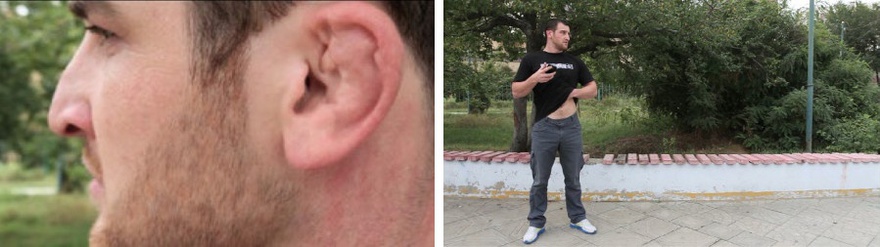

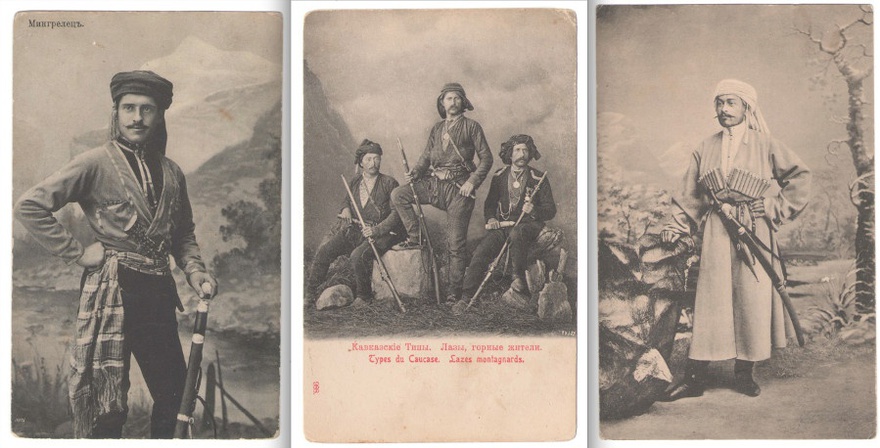

TM: Great halls! Ours accommodate up to 1000 people only! My own wedding was in a hall called Marrakesh and its maximum capacity is 800 people. Two years later I shot a work in that hall called A Space of Celebration (2009), which was also a reinterpretation of current wedding culture. I live life first, and then make work about it. In Dagestan, I think lavish weddings are more about family status than a mark of masculinity. My husband, however, did inspire my choosing to focus on masculinity as a subject matter… this is only partially a joke. By looking at him and his friends I became more aware of how and by which means masculinity is formed today. Society is culturally very macho due to economic collapse, unemployment, and corruption, and society in such a state ends up constantly emasculating its subjects. Masculinity becomes absolutely performative, but there are not enough tools today to reflect on this changing notion of masculinity. Freestyle wrestling is the most popular sport in the region, most of the wrestlers have broken ears. Perhaps a good example of the 'performative masculinity' I have mentioned are videos of men breaking their ears on purpose in order to be classified as wrestlers at a first glance. It is similar to a practice of the times of Caucasian War, when the majority of men dyed their beards with henna and were even called 'red bearded': this served as an additional mechanism to install fear in the enemy.

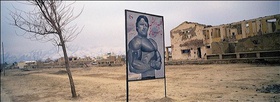

LA: Wrestling is also a big sport favoured in most countries in Central Asia, but bodybuilding is really huge in Afghanistan. Below are a few images of works by artists that relate to a form of over-the-top, pop male performativity.

It also makes me want to reference my work Vocabulary (2012) which is my collection of male public gestures and is similar to Bruno Munari's book Speak Italian: The Fine Art of Gesture, which also deals with affirming male presence in the visible space.

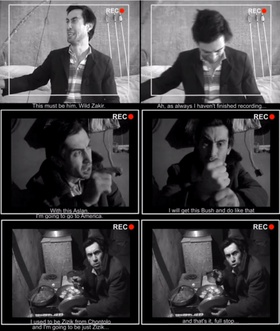

There is one very important work by my friends that have also influenced my interests. Zizik is a 30-minute television production by Murad Halilov and Hadzhimurad Nabiev, released in 2010. The film's main character is Zizik, who is faced with several dilemmas. He recently got divorced from his wife, and her brother Wild Zakir is trying to throw him out of the house he lives in because his ex-wife had transferred ownership to her name. He has no job and is quickly running out of food. One of Zizik's coping mechanisms is the production of videos where he talks directly to camera in confession mode.

I'm running out of food. This is the last potato I have. My wife's brother is coming soon to throw me out of my house. This bitch, my wife even registered the house for her name. Her brother will come to throw me out. Who will I be then? I used to be Zizik from Chontolo and I'm going to be just Zizik... and that's it, full stop.

The film presents us with an introspective, male, self-critical voice that is struggling to deal with his own reality and has wider repercussions against the political state. The viewer witnesses Zizik's emasculation in the domestic sphere of his own home and in a wider political sense throughout the film. One of the reasons this work came into existence is, I believe, related to the formation of a new male identity. Through humour, the directors of this work have deconstructed a traditional, archetypal masculinity of the Dagestani male. The whole film is about the notion of masculinity in crisis.

Going back to your question about the choice of medium: I do not think I have made a definite choice. It was mostly video in the beginning, because it offered a more complex conversation with the audience than photography ever could. But in the past few years, my practice has been expanding into objects. Since I moved back to Dagestan after my MA, I have started obsessively collecting things, be it a real collection of postcards, noses, a more ephemeral one of gestures, or even Soviet signs, which are rapidly disappearing from Makhachkala.

I can speak about methodology, but not style. It is greatly influenced by other artists whose work I love. In Gamsutl (2012) I used a similar approach to John Gerrard's when he worked on military bases, collecting war posture instructions and manuals. In the same work, at the very beginning I was influenced by DV8 Physical theatre works, which made me consider choreography and think in that direction. I tend to collect visual and conceptual decisions from other works and everyday life, place them into various folders and then rearrange them for my own work.

LA: That's very intriguing; the concept that we are owners of our own ideas is a very false one, at least from a Sufi perspective, which predicates that everything loops inward and out, while linking back and forth in time. So your collection of references and inspirations, by which you complete another work, or deconstructto highlight another point of view inclusive of what has come before but also of what comes after, is a kind of an unravelling of that inner studio that I am speaking about. Your process reminds me of another dear artist I work with, Vyacheslav Akhunov and his vast number of secret drawings, installation plans, and collages, made between 1970 and throughout the 1990s in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. They were largely drawn from his obsessive practice of studying, collecting and archiving absolutely everything within the collective conscious of his local Uzbek, Soviet arena, and beyond. Isolated from half the world by the divisions of the Cold War era, he absorbed the paraphernalia of his environment in such a manner as to be able to penetrate through all barriers, making critical works that are monumentally present to the eras he lived in, conscious of the past, while brilliantly projecting future scenarios.

Artists are consumers of ideas, but the best of them consume in a healthy way, which involves processing what they consume, which is a very unconventional way of educating oneself. The sum total of many ideas becomes one's own by applying a conscious process for comprehension. This is a different kind of education. Akhunov's preoccupations with Sufi, Chinese, and Zoroastrian philosophies for example, merged with his secret explorations of Nietzsche, Heidegger, Benjamin, Adorno, Marcuse, Horkheimer, Camus, Sartre and Foucault rendering him not only his own best student but also his own best teacher.

You mentioned your experience at Goldsmith earlier. I consider most credited programmes in a university setting formal education, and there are of course ranges of formality and informality. I wonder what are some other types of trainings (self-education) that have been useful to you as an artist? How?

TM: I think the UK system is very much self-driven and I am not sure I can distinguish between self-education and the university-format education I received. I think my own teaching experience was, and is, one of the most useful things; when I prepared a course of lectures for the first time for Moscow State University, I was finally able to structure the history of performance art in my head.

LA: Going back to your having moved more towards making and collecting objects since your return to Dagestan, compels my thinking once again about collective artistic spaces and traditions. Asia as a whole continent, for example, historically has engaged significantly in the following realms: texts, images, and objects. In late September, I was invited to Doha by Abdellah Karroum to conduct a week-long curatorial workshop at Mathaf. A great visit, which also provided me the opportunity to experience the remarkable Museum of Islamic Art in Doha. The majority of this museum's vast collection comes from Central Asia (Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan) and Western Asia (Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon). I was blown away by the immensity of object-making traditions in these regions that are essentially unparalleled; all possible disciplines from science to poetry, philosophy, mathematics, geometry, to astrology and so on, were contemplated through one form of object making or another. Are there some specific Caucasus aesthetic or artistic traditions, present or historical moments that your works are inspired by? Or that may be referencing in some direct conscious or indirect unconscious ways?

TM: Certain subject matters that were, and are, present in the local artistic traditions I reinterpret and question, perhaps a good example is my work Portrait of Avar (2010). This work problematizes a current representation of a woman from the Caucasus region and it updates a dialogue that took place in Dagestani painting tradition that was mostly concerned with a way to represent beautiful, hardworking and modest women from a patriarchal society. Perhaps a series of new works, called SuperTaus (2014), inspired by my friend Sohrab Kashani's series, The Adventures of SuperSohrab (2011). The first video is the beginning of a series about a mountain woman superhero, who, in this particular instance, moves rocks like pebbles. I would like to think about this work as a continuation of a wonderful work, by my favourite Dagestani artist, Galina Konopatskaya; the work is Cosmic Mother (1970).

LA: Continuing along the lines of how we experience evolution, I am interested in the thread that either breaks at times or reconnects to elements of our practice continuously. I view my own curatorial work as the nurturing of a being into various stages. How does your current portfolio fit into the rest of your body of work from earlier periods?

TM: Hardly, Slightly, Partly.

If I look at my portfolio, which I just opened, I think almost every work takes, as a starting-point, an observation that I make on the city of Makhachkala today. I think being in this particular place and experiencing it is crucial for my artistic production. If you take the work Growth (2014–ongoing), it's an observation on how facial hair changed with ideology in the region. Another work, Landscape, was partially inspired by my native language where the word for 'mountain' and 'nose' is both one and the same. It also stemmed from the works and conversation with a wonderful ethnographer U.U.Karpov.[2] When I was consulting him for Gamsutl (2012), he mentioned a fable about men who lose their noses and have to perform some heroic deeds in order to gain them back. I think, taking this kind of a side road as aknowledge, which operates outside of so-called critical theory, is what drives me the most.

Also my work, Way of an Object (2013), is an attempt to liven up a local museum and imagine a more active role for the currently-dead artefacts in it. The work was created out of inspiration from Wael Shawky's Cabaret Crusades (2010–ongoing) and my long-lasting love for the best puppeteer in the world, Ronnie Burkett. Works of my colleagues and other art-related practices have a huge impact on my way of thinking and constructing works and simply on my drive to make things.

LA: What would you say is the purpose of making art?

TM: It's change. I am and I feel changed after seeing works of other artists and I want to be able to do the same thing. It's a gateway to reconsideration of your reality. Art is a major catalyst for critical thinking. It's about making several centres in your body swirl – this is exactly how I feel when I look at the works of Wael Shawky, Basim Magdy, Agnieszka Polska, Akram Zaatari, Chris Marker and the works of so many more. For some reason a 1973 work, Mom-Me by Larry Miller is ringing in my head at the moment. A body of work that was realized under hypnosis, where the artist was hypnotized to think he was his mother.

LA: So much of what we are made aware of these days about recent and historical events are partly due to the great inquiries launched by artists as part of their artistic endeavours. Mariam Ghani, Haig Aivazian, Shilpa Gupta, and Naem Moheimin's works are great examples of such practices. I would like to end our studio visit by asking what are your thoughts on your local art scene or the international art market, art education or system for exhibition of art?

TM: I would like to respond through a video project I am currently working on as it deals with the invisibility and instability of the current art situation in the region. Two recent events propelled the concept behind the work I am in the process of making. First, shortly after being appointed as head of the Republic of Dagestan, Ramazan Abdulatipov ordered the Dagestan State United History and Architecture Museum (named after Alibek Takho-Godi), to move into a new building; giving them only one week's notice to transfer one of the biggest art collections in the region. The second event was a research session, where various focus groups were discussing developments of the city of Makhachkala. During the final sessions, the head of the government decided to briefly leave the room exactly during the presentation of a group focusing on culture, and the only group that was chaired by a woman. This made me realize that in recent history practically all of the directors of art museums, and ministers of culture in Dagestan, have been women. Generally speaking culture is silenced and is sitting in the back row. The video work addressing these two events will depict tightrope walkers in the mountains of Dagestan, in the village Tsovkra. The tightrope walkers will be walking on wire, but will be balancing not with balance poles or other tools, but the artworks of various artists from Dagestan. Paintings, drawings and small-scale sculptures; the works will span through the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, telling the story of various subject matters in the local art history. Some of the works will be originals loaned by artists and local museums, while others will be copies produced for the video.

Follow this link to view the project 19 a Day by Taus Makhacheva.

Taus Makhacheva was born in 1983 in Moscow and lives and works in Makhachkala and Moscow. She holds a BA in Fine Art from Goldsmiths College, London and an MA from the Royal College of Art, London. In 2014 Taus Makhacheva won the Future of Europe prize at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Leipzig, and in 2012 she received the Innovation Prize, the Russian state award for contemporary art in Moscow, the 'New Generation' category, for her project The Fast and The Furious.

Selected solo exhibitions include: A Walk, A Dance, A Ritual, Museum of Contemporary Art, Leipzig, Germany (2014) and Story Demands to be Continued, Republic of Dagestan Union of Artists, Makhachkala, Russia (2013).

Selected group exhibitions include: Love me, Love me not, Collateral exhibition, 55th Venice Biennale (2013); Re: emerge – Towards a New Cultural Cartography, Sharjah Biennial 11 (2013); City States – Makhachkala, Topography of Masculinity, 7th Liverpool Biennial, (2012); Rewriting Worlds, ArtPlay Сentre, The Fourth Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art, (2011); Greater Caucasus, PERMM Museum of Contemporary Art, Perm (2011); Affirmative Action (Mimesis), Laura Bulian Gallery, Milan (2011); Practice for Everyday Life, Calvert 22, London (2011); and History of Russian Video Art, Volume 3, Moscow Museum of Modern Art (2010).

[1] Nevesta (translation: Bride) (Khasavurt), Summer 2014; Nevestan (Dagestan), Summer 2014; Nevesta (Derbent), Summer 2014; Empire, Spring 2014; Svadebnii Dagestan (translation: Wedding Dagestan), Number 17; Svadebnaya Legenda (translation: Wedding Legend), Number 24, 2014.

[2] U.U. Karpov, Vzglyad na Gortsev Vzglyad s Gor (Saint-Petersburg: Peterburgskoe Vostogovedenie, 2007).