Interviews

The Tentmakers of Cairo

Kim Beamish in conversation with Sam Bowker

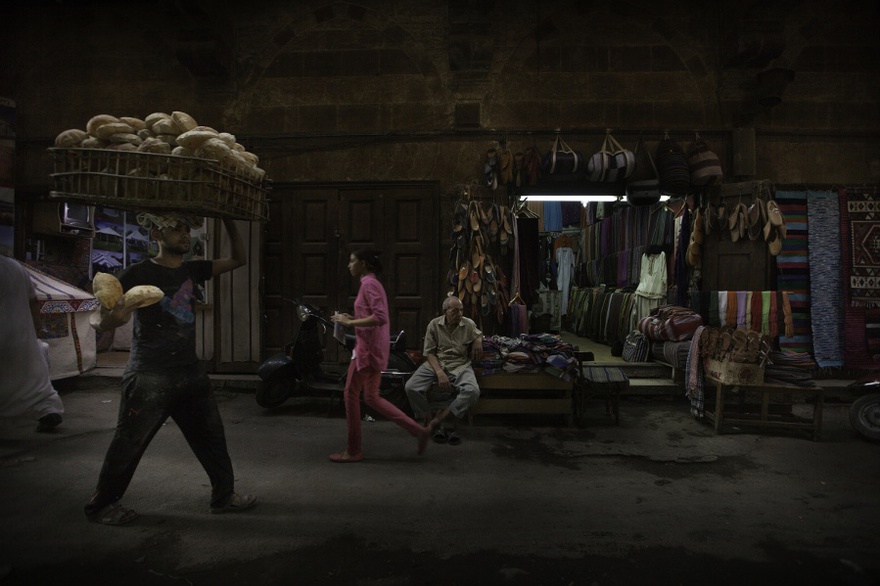

The Tentmakers of Cairo (2016) is a feature-length documentary that situates Egypt's post-2011 political landscape through the perspectives of a unique community of textile artists. Over three years, Kim Beamish intimately filmed the interactions of the tentmakers with local, national, and international narratives, blending news media and authentic dialogue with the visual and cultural complexity of Khayamiya, or Egyptian Tentmaker Applique. This interview discusses his experiences as a documentary filmmaker in Cairo and the situation of khayamiya in contemporary Egyptian art.

Sam Bowker: Your film is the first documentary told from the perspective of the tentmakers of Cairo. How did this project begin?

Kim Beamish: It started when I was filming for the Australian National University in Canberra. Every time journalists wanted to talk to academic experts, Professor Robert Bowker would answer their questions about the 'Arab Spring', Egypt, Tunisia, Syria, and so on. So when I found out that we were going to move to Egypt for my wife's work, I asked him about it. I was hoping for stories about political activists, but he kept coming back to the tentmakers. At first I was not all that enthused – they sounded interesting, but I wanted to learn about other things. We met with Robert and Jenny Bowker before leaving and it turned out that we were going to be in Cairo at the same time. So Jenny arranged to meet me on 26th July Street and took me down to meet the tentmakers. As soon as I arrived with Jenny, who has worked with the tentmakers as a curator since 2007, the whole street accepted me.

A major rule of documentary filmmaking is 'access, access, access'. As I realized how beautiful the tentmakers' artworks were, I could see this becoming a way to venture into Egyptian society. It was another way to tell an observational story of Egypt.

SB: How do you see your film in comparison to other recent documentaries from Cairo, such as Jehane Noujaim's The Square (2013)?

KB: The Square was always in my rear view mirror. Because of its Oscar nomination, the scale and publicity around it, it was always other people's first point of reference. People would ask me, 'Why should we fund your project, when we already have The Square?' Both films were crowd-funded.

But I really wanted to tell a story about the 98 per cent in Egypt. If you look at revolutions in world history, only one to two per cent fight for revolutions. 100 per cent have to live through them. For me, The Square centres on the two per cent: the protagonists, while The Tentmakers of Cairo is about the 98 per cent of Egyptians. It was filmed over three years during an ongoing revolution. It's about how the events of The Square have become part of the daily lives of the Egyptian people.

SB: I understand that your reading of the work of Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz also influenced your approach to The Tentmakers of Cairo. What did you find useful about his work?

KB: When I was researching the tentmakers I started looking for references to them throughout literature, film, visual art; anything I could find. Several people suggested Naguib Mahfouz's Children of the Alley (1959), so I read it, but it made no references to the tentmakers, or khayamiya, at all. However, it was an important story because it was about what I wanted to show – a story of the lives of Egyptians, drawn through metaphor.

In Mahfouz's book, there's an overlord: a gangster who has three children. At different points he expels the children and brings them back – they are representative of the three religions Christianity, Judaism, and Islam – and these characters were based on how Mahfouz interpreted their reactions as religions. The use of metaphor is very important for The Tentmakers of Cairo because in the film the people, their interactions and conversations, the setting, and the textile art itself (khayamiya) are social, cultural, and political metaphors.

If you look at the way the tentmakers sew applique, it's like no-one else in the world – their process is unique to Egypt. On that note, I think the way they are moving around democracy is also unique to Egypt. One of my favorite billboards in Cairo after the protests of 30 June 2013 was the declaration that: 'We are fighting terrorism in order to protect our manifestation of democracy', which sums up that idea. The whole film is a metaphor for this movement through democracy, trying new things out but really wanting to stick with the old.

SB: Did the way in which khayamiya is made influence your film?

KB: I came into the story unsure of what I would do with the subject. There is a direction I could have taken, which was more historical, looking at where khayamiya had come from and how it became what it is today, through style and technique. To do this I needed to show the making process, so I commissioned Hossam Farouk to make a large piece so I could film this from beginning to end. I wanted to go through the initial drawing, the transferal of the design by pinpricking and poncing, attaching each piece of applique by hand, every single step. This created about three months of filming, and that was going to be the initial storyline. The final shot was going to be the final stitch, but as I was filming, everything changed.

While Hossam was sewing, he was listening to the radio or watching the television all the time. That's when I saw the political film that I actually wanted to make – it emerged around me as I watched from the street of the tentmakers. I could stay within this changing community and see what everyone was saying, but no-one was filming.

The beauty and imagery of the film is in the way the khayamiya artwork is brought together. This enables us to see and listen to what was happening in Egypt, and how it was being interpreted, without leaving the microcosm of the street. I did not need to run into police or protestors. The stitching of the khayamiya became the metaphor to bring their narratives into one film.

SB: Following the experiences of the Al-Jazeera journalists Baher Mohamed, Mohamed Fahmy and Peter Greste, who were given seven-year prison sentences in June 2014, did you ever feel at risk when filming in Cairo?

KB: I always felt it on the way to the street. My camera and tripod, when I used them, are not small. To reach the street of the tentmakers, you have to walk past the central police station of Cairo, where a lot of activists were held for questioning. Many of the other photographers I'd met during the filming had their cameras smashed. But once I was on the street of the tentmakers, I was not worried. Within a couple of weeks, one of the elders of the street took me to have a koshary lunch. He took my arm and marched me through the street, which signaled to everyone that I was alright and that I was there for good. After that, even the people who did not like me much (and there were a few) would even look out for me. If the police came I was hidden in a different shop, if the Ministry of Antiquities turned up I was ushered away until they left. I had a couple of occasions when I was questioned, but the community behaved in an organic way – they would surround me and the person doing the questioning, then whisked me away as they kept the questioner in place with counter-questions. I felt safe there because we trusted each other.

If you start filming with any kind of camera in Cairo, you will be surrounded in moments with questions – or people staring down the lens. They are worried you might portray Egypt in a bad light or maybe that you are a spy. It's a mixture of paranoia and simply not knowing what a camera is. For non-Egyptians it's difficult to film initially in Cairo, but once you have local trust and support from that area then it's not a problem at all.

My first studio in Cairo was in Darb 1718, which is the artist Moataz Nasser's project. It is a contemporary art space that hosts lots of Egyptian artists, sculptors and media makers. I rented studio space there, which was great, but because the location was not good for my situation, I moved to another studio in Dokki supplied by Mohamed Samir and Day Dream Art Production. He is one of Egypt's up-and-coming directors and he was really helpful.

SB: Contemporary artists like Rachid Koraichi and Moataz Nasr have collaborated with the tentmakers of Cairo to produce new installations and textile artworks. Do you think we will see more of this collaboration in the future?

KB: I think so. It's more about the artists approaching the tentmakers to create new works. The tentmakers will do anything they are interested in and paid for, so collaboration is important but will need to be driven by the Egyptian artists. They bring new ideas to khayamiya, like Moataz Nasser, who during the Iraq War collected flyers that the Americans dropped over Baghdad. He commissioned the tentmakers to stitch these flyers as new pieces. Rachid Koraichi made a huge installation – The Invisible Masters (2008) – of white banners with his own calligraphic inscriptions, all sewn by the tentmakers. I think the tentmakers are a resource that Egyptian artists will use more, once they realize it is out there.

SB: To your view, how is the artwork of the tentmakers of Cairo regarded in Egypt? Is that consistent with the reactions of international audiences?

KB: When Egyptians know about it, it is regarded really well. They admire it and recognize the level of design, skill and detail that goes into it. But it's not common knowledge. Many Egyptians attended the Cairo screenings of the film, but the majority did not know about the artwork or the location of the street. They have seen the printed versions of these textiles through the tents used at weddings and funerals and so on, but they did not connect these structures to the hand-made artwork. There's a lightbulb moment when they make the connection that khayamiya is more than these factory-printed sheets.

From an international perspective, when travelling with the tentmakers in the UK, USA and France, everyone is astounded by it. It's really, really different – especially if they know about applique or quilting or textile art – so there is a lot of interest in khayamiya overseas. The tentmakers work in ways that are not seen elsewhere. For international audiences, it's more than the beauty of the work. It's the way they do it, the men who are sewing, and that this is an unknown part of Egypt.

The tentmakers represent a Middle East most of these audiences knew nothing about – culturally or in terms of the artwork. It was a different way of seeing the Middle East. These guys were willing to talk and show how they worked. They were seeing Arabic text on beautiful, well stitched, colourful khayamiya – nothing like the black and white flag we all see on the news.

When the tentmakers were overseas, they were very happy to see the reactions. There's a scene in the film where they talk about the reactions they got overseas. But it's one thing to get recognition aborad, and another altogether in Egypt.

SB: One design in particular, the Revolution Khayamiya, by Hany Abd el-Khader, plays a special role in your film. What set El-Khader's work apart from the other tentmakers?

KB: The fact that he made a narrative khayamiya piece about the 2011 Revolution set him apart. It was a deliberate political statement. They are devout Muslims, so seeing human figures is rare in their work. Hany used his art to make a commentary on Egypt and its recent history, which was very unusual. The Revolution Khayamiya was made to get a trauma off his chest – and for several reasons, Hany was one of the few tentmakers who saw a lot more confrontation than the others. But it was more than his way to work through it – he took it to France and showed people there, which was a proud moment for him as an Egyptian. Through khayamiya we found our own ways to explain the impact of the revolution.

View the trailer to The Tentmakers of Cairo on the Ibraaz Channel here.

View the trailer to The Tentmakers of Cairo on the documentary's website, and keep up-to-date with the project here.

Kim Beamish is an award winning Australian filmmaker who filmed, directed and produced The Tentmakers of Cairo. He studied at the Victorian College of the Arts, Film and Television School after having spent many years volunteering with community television station Channel 31 as well as working with Open Channel and Ska TV in Melbourne, Australia. In 2006, Kim co-produced the film Just Punishment about the fight to save Van Nguyen from execution for drug smuggling in Singapore. Kim is presently researching new projects as well as working as a journalist and running his production company Non'D'Script.