Interviews

Revisiting Internationalists

Fadi Bardawil in conversation with Zeynep Oz

The following is an email conversation that took place following Fadi Bardawil's lecture, which was delivered as part of a series organized by Zeynep Oz at SALT Galata in February 2016. Run in collaboration with Fol Cinema, 'Greatest Common Factor' reconsidered the moments of political hope, uncertainty and disillusionment in the 1970s through film screenings, lectures and a roundtable discussion at SALT Galata and SALT Ulus. On the second day, Bardawil gave a talk titled 'The 1960s' New Left and Its Becomings: Disenchantment, Anabasis, Haunting'. The talk discussed the rise of the 'New Left' in the Arab world and painted a picture of a world characterized by a critique of the logic of professionalization and expertise, as well as of a time of heavy traffic in theories, forms of solidarity, and modalities of political practice.

Zeynep Oz: At the beginning of your talk, you outlined the relationship between the diplomat and the artist. You keep coming back to this relationship with all its interdependencies, its contradictions, and its symbiosis. Is it fair to describe the interest in this relationship as the main thread through which you read the resistance movements at the end of the 1960s and beginning of the 1970s in this talk? And if so, could you summarize how you read this thread?

Fadi Bardawil: I have been engaged for the past few years in unearthing the neglected archive of the Levantine New Left, which came into being in the late 1960s, and its internationalist connections. In digging out these veins part of what I am doing is excavating a history that is not bound by the borders of nation-states and the boundaries of religious traditions. I don't do that out of an antiquarian's interest in the past though, but rather to gain a better grip on our present by troubling what we take for granted through unearthing those older visions of emancipation, modalities of political and artistic practice, and forms of collective organization, as well as the conjunctures that enabled them and which they intervened in.

In doing so, I steer clear of two widespread readings of the 1960s and 1970s Left: the Left-melancholic frame and the Liberal-triumphalist one. The first is still attached to what it perceives as a 'revolutionary golden age'. This was a time when the world was wrapped in one overarching ideological canvass which clearly pinned down the progressives and the reactionaries in the four corners of the world. The Left-melancholic witnessed the extinction of revolutionary hopes and the marginalization of his conceptual arsenal of class struggle and revolutionary masses with the increased authoritarianism of the Arab post-colonial regimes; the Islamic revival that brought back questions of authenticity and foreignness; and the rise of infra-national sectarian and ethnic solidarities that proved stronger than those articulated on class interest. In response to the ebbing of revolutionary tides the melancholic reifies this past moment of hope and is reluctant to engage our present predicaments and to critically assess the role of the 1960s Left in fashioning the contours of our recent past and present. On the other hand, the Liberal-triumphalist disparages that past on the grounds that the Left has failed both when it reached state power and when it opposed it. More often than not, the Liberal-triumphalist clams that the Left degenerated into authoritarian government, a party in civil wars, and senseless violence. For the Liberal-triumphalist, nothing is worth revisiting from this failed tradition of thought, art, and political practice. Part of my interest in Eric Baudelaire's film The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi, and 27 Years Without Images (2011) lies in how his own positionality that leans on the notion of Anabasis – which in Greek means to embark and to return and that Badiou interprets as leaving undecided what is allotted to disciplined invention and uncertain wandering – manages to escape re-capturing the past through these dominant frames. How can we re-read this past, in and for our present, outside of these melancholic and triumphalist frames? And would the recovery, activation and reworking of some of these past kernels help us to critically assess and engage the events that constitute our present landscape? These are the questions that animate my work.

After this detour, I come back to your initial question about the personal relationship between the Palestinian PLO diplomat (Ezzedine Kalak) and the French engaged artist (Claude Lazar) in 1970s Paris. I came across the details of this relationship after I was invited by Rasha Salti and Kristine Khouri last year to take part in a seminar at the Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) around Past Disquiet: Narratives and Ghosts from The International Art Exhibition for Palestine, 1978 (2016) the archival and documentary exhibition they curated.[1] Rasha and Kristine's impressive research material, which I drew upon, excavated a discursive and visual archive of anti-imperialist solidarity around Palestine that connects Japan, Lebanon, Italy, Jordan, Paris and Chile amongst other places.

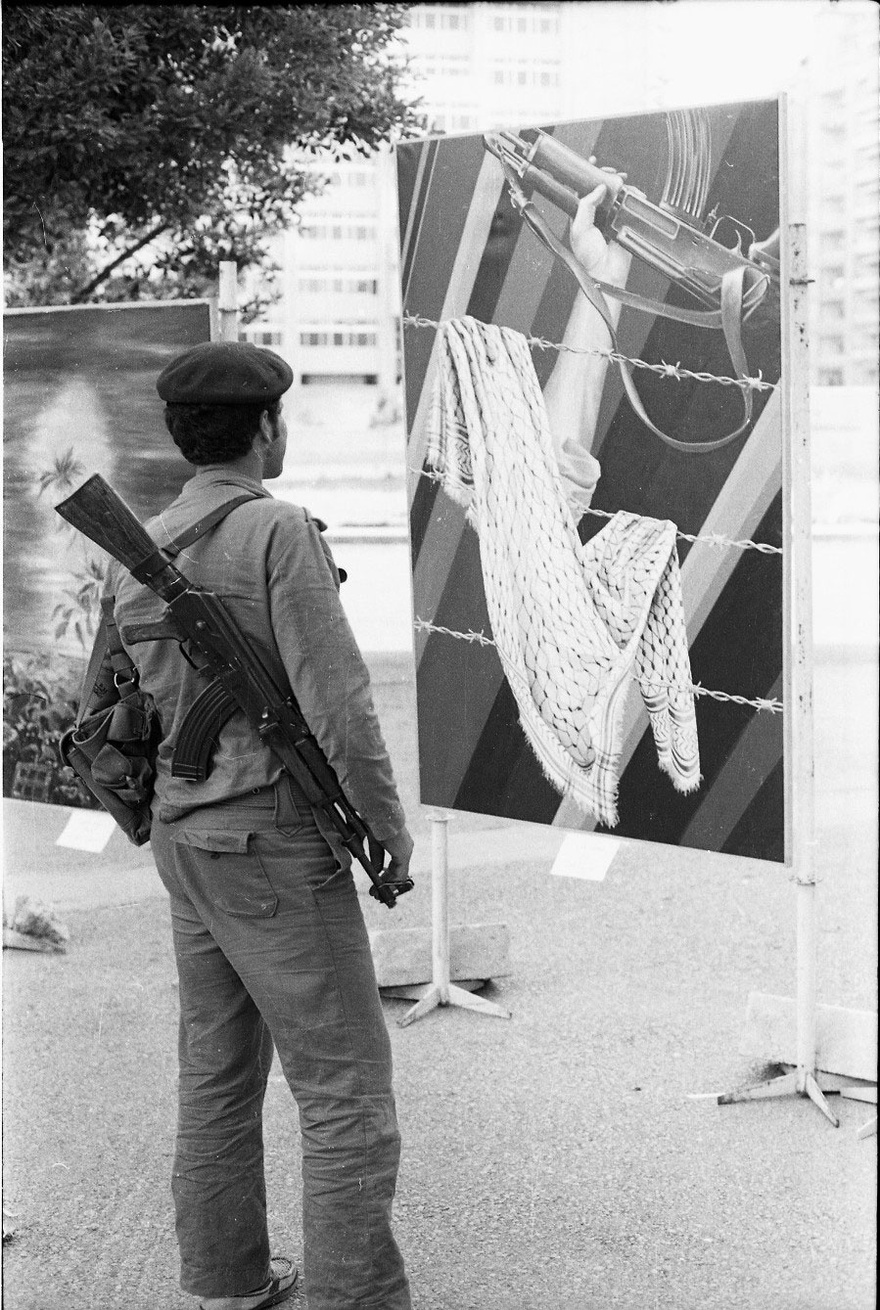

From the intimate details of the friendship and working relationship between these two individuals I wanted to sketch the wider contours of a time of internationalist solidarity when both art and politics, the figure of the diplomat and the artist, as well as east and west partook in a common revolutionary tradition. Moreover, I wanted to highlight the fact that being part of a common tradition was far from dictating a smooth uniformity of positions but was rather premised on an intense circulation, negotiation, and transfiguration of theories, aesthetic forms, and modalities of political practice. For instance, Kalak, Lazar recalls, used to criticize the saturation of his posters of Palestine with forests of Kalashnikovs, alluding in the process to the Parisian revolutionaries' fetishization of armed struggle and how this particular politics of representation risked pigeonholing Palestinians as 'madmen of the revolution'. The two friends also spent some time discussing ideas for a contemporary art museum for Palestine in the wake of the formation of the museum of resistance in exile in support of Salvador Allende after Pinochet's 1973 coup in Chile. This artwork was being produced and those conversations about Chile and Palestine were taking place in Paris while the Arab New Left was thinking and debating the Palestinian fedayeenaction with the Chinese, Cuban and Vietnamese theories, organizational forms, and military strategies in mind.

This was a time of intense traffic in, and translation of, theories and strategies that was not premised on notions of cultural incommensurability between self and other. There were of course some voices that saw in Marxism and the revolutionary tradition a foreign import but they were certainly not as prominent then. The Iranian Revolution in 1979 and the Islamic revival would fold the Third-Worldist moment and its internationalist dimensions by repositioning Marxism from a universal theory of emancipation to one form of Western cultural imperialism. After a decade or so of internationalism, older 'cultural' binaries resurfaced. Questions of self and other, authenticity and modernity, Islam and secularism would occupy centre-stage and interrupt the internationalist circuit of traveling theories and militants. Even at a very basic and practical level, westerners in 1980s Beirut became a potential target for kidnappings by newly formed Islamist militant factions. Within just a few years, trips like the one Claude Lazar took in 1978 to participate in the PLO sponsored International Art Exhibition for Palestine in Beirut, became impossible.

At the same time as the question of 'Culture' was displacing the revolutionary foot soldiers of History – just think for a minute of Althusser's philosophy student Régis Debray who joined Guevara, was imprisoned for a few years in Bolivia and wrote on the doctrines of guerrilla warfare – they were also side-lined by the rise of a new form of internationalist intervention: Humanitarianism. Anthropology's non-western 'natives' became Third-World comrades in the 1960s and 1970s before turning into Global South victims in need of humanitarian rescue from the 1980s onwards. Humanitarianism also increasingly asserted the logic of expertise as it became more and more professionalized, turning into a recognized, and sometimes lucrative, career path.

This brings me to my last point regarding the diplomat and the artist. Their relationship, which transgressed national, class and professional boundaries, captured the signature political sociability of these times. This sociability, as Kristin Ross notes, was characterized by dislocating individuals from the social world they were groomed to inhabit.[2] By displacing them, this form of sociability partook in the fashioning of their political subjectivities – you can also think of Debray and Guevara here as well. To wrap up, I would say that through my exploration of this relationship I seek to capture the wider contours of internationalist solidarity, its circuits of circulation and transfiguration, as well as the processes of fashioning political subjectivities against the logic of professionalization and expertise; what Jacques Rancière dubs the logic of the police – the one of assigned roles and stations.

ZO: At some point in your talk, you mention the politics of secrecy. You define it in terms of real-politics and the fact that a number of the members of Socialist Lebanon were public servants and thus could not sign their militant texts. On the other hand, you also touch upon the fact that the non-signature was a result of the ruminations on the relations of production, a certain criticality towards the idea of the individual author. Could you expand on the erasure of signatures? And how do you see the difference between the idea of the individual author in the political and the aesthetic realms? Both in terms of how it functioned at the time, and now. Do any of these distinctions have a legacy in the perceptions of the author in these realms today?

FB: The Organization of Socialist Lebanon (1964–1970) was a Marxist group that had an overwhelming representation of militant intellectuals in its midst, some of whom would later become prominent academics and public intellectuals – such as Waddah Charara, Ahmad Beydoun, Fawwaz Traboulsi, and Azza Charara Baydoun to name a few. While working in this archive I noticed that none of the articles they published in their underground mimeographed bulletin were signed. While conducting interviews with the individuals about 40 years later, they mentioned that the organization was a vibrant intellectual hub of reading, discussion and translation. They were reading theorists such as Bourdieu, Foucault, Althusser, Fanon, Lacan and Castoriadis. The only noms propres that would appear in the mimeographed bulletin however were those of authors who were strictly part of the revolutionary tradition, such as Marx, Lenin, Mao, Guevara and Castro; even though I could detect the influence of particular theorists, such as Bourdieu's sociology of education in a piece on student mobilizations. This double erasure – of their own names and of the theorists they were reading – got me interested in questions of authorship and the various performative labours of theory. So I began asking straightforward questions such as, how is theory embedded differently in political, academic and artistic projects? And what does it authorize?

In Socialist Lebanon's case, the erasure of the author's signatures was, as you mentioned, related to a few things. Some of the members were public school teachers at the time, which made it difficult to write under their own names while calling for a revolution against their employer. More importantly Socialist Lebanon subscribed to a collectivist ethos. They were not unique of course. This was a time when collectivist ideals were widespread in political and artistic practice. For instance, the Dziga-Vertov group, which included Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Henri Roger and Jean-Pierre Gorin, was founded around the time of student demonstrations and workers' strikes of May 1968, around four years after the establishment of Socialist Lebanon. While Claude Lazar met Ezzedine Kalak around 1975 after he founded a Palestine Collective in the Jeune Peinture artist association that ironically had him as the only member in its beginnings.

At the heart of these collective endeavours is an attempt to transform the relations of production and to re-articulate artistic and intellectual practice away from the bourgeois notion of the individual author and the tortured romantic genius. And by the way, it is the modern period that ushered in the age of democratic equality between citizens (politics), commensurability (statistics) and the destruction of the aura (art) that also gave rise to the notion of artistic and scientific genius that re-introduced a principle of qualitative hierarchy between mere equal mortals and the pantheon of secular gods – for example, Shakespeare, Picasso and Einstein. In erasing the noms propre of the artist – the Dziga-Vertov Group's films did not include individual credits – these collectives, sought to break away from the fetish of the name of the master which, as Bourdieu noted, transforms the social nature of the object by bestowing upon it a symbolic value.

This brings us out of the site of production and into the sphere of circulation of commodities, where the artwork, associated with the name of the master, also acquires an exchange value. The erasure of credits as well as the circulation of artworks outside of the market, by bringing it to the people and showing it in non-commercial venues such as factories, public spaces and universities, were all efforts to circumscribe turning art into a commodity with an exchange-value that will overcome its use-value. Very early on Adorno observed in his polemic against Benjamin's thesis on the emancipatory potential of art after the destruction of its aura that the consumer of cultural commodities is really worshipping the money he paid to attend a Toscanini concert.

While Socialist Lebanon initially included prices on their underground bulletins, the organization ended up also distributing their underground bulletin for free. In their own case, the erasure of personal names served them well because the Lebanese Communist Party, and other political parties they were subjecting to a ruthless critique on their pages, could not assess the size of the theoretically sophisticated underground organization. In fact, the main contributors to the bulletin were just a few and the organization had around 30 to 40 members in its first years and reached a few less than 100 in the late 1960s.

More importantly, the erasure of the names of theorists from the bulletin was related to the means of production of revolutionary authority. Waddah Charara, Socialist Lebanon's main theorist, mentioned in one of our conversations that his militant voice was partially a consequence of not wanting to be taken for a 'farfelu (eccentric) intellectual' tinkering with culture, in contrast to a revolutionary, grounding political practice in a Marxian theoretical analysis. In that sense, Waddah Charara and Jean-Luc Godard had reverse trajectories. Godard was already a recognized filmmaker when he founded the Dziga-Vertov Collective. His critique of the individual author is an auto-critique of sorts and the moment of the collective (1968–1973) is retrospectively a milestone in Godard's career. While in Charara's case most of what he was publishing for a decade or so was not signed or was put out under pseudonyms and written in a militant voice. He was not an auteur who turned into a member of a collective, but an anonymous foot soldier of History, a comrade, who leaves his personal name and his individual desires behind to work for the revolution and recovers them in the wake of revolutionary disenchantment. The transition from artistic authorial fame to collective work is very different from emerging from years of underground political work to a recovery of your own personal name and of the craft of writing without a mission.

The labours of theory, and the name of the theorist, that were put to use to analyse a particular situation and authorize political practice had to be hidden, as I mentioned. This is also very different from theory's use in academic settings where it bolsters the authority of its user, endowing him with a high cultural and symbolic capital. How many times do we hear seemingly innocuous whispers such as 'his work is OK, but not theoretical enough…', meaning its conceptual engines are not big enough to take off and go on universal trips, hopping from one place to another. From a book editor's perspective, a work's theoretical deficit these days means taking a risk of putting out a monograph with a limited readership. 'What is your theoretical contribution to the field?' asks the editor, or 'Why would anyone who does not care much about the late Ottoman Levant read your book about the transformations of Tripoli's urban fabric in the 19th century?' Theory in certain corners of the academy is a highly valued lingua franca that circulates between, and brings together, the speakers of different disciplinary and regional dialects. Not speaking it risks consigning your work to invisibility and a limited reach, to the fate of an autochthonous provincial intellectual.

In an article published a few years ago investigating the relationship of modern and contemporary art to theory, Boris Groys mentioned that conceptual discourse does not only come after the production of the artwork by the theorist who mobilizes it, promotes it and legitimizes it. Rather, and more interestingly, Groys suggests that theory precedes the production of art by artists who draw on it to explain to themselves what they are doing, and as such, 'it liberates artists from their cultural identities – from the danger that their art would be perceived only as a local curiosity'.[3] Groys' observation regarding art has points of contact with the academic use of theory. In both cases theory is the medium to universality. That said, one could ask the old sceptical question about the unequal distribution of the conditions of access to the universal: Is liberation from 'cultural identity' via the medium of theory equally distributed on all artists? Or are some urged to engage and perform particular notions of 'cultural identity' to gain global recognition? Just think for a moment on the demands put on Arab jazz musicians to play 'Oriental Jazz,' or on Arab philosophy students to specialize in 'Islamic philosophy' and so on. And even if one clearly avoids dabbling with 'identity', the logic of cultural institutions sometimes ends up classifying it as 'X art', substituting X for nation, ethnicity, gender, religion and race.

Beyond the academic world and the contemporary art scene, one could ask: how are notions of authorship and the politics of representation shifting with the proliferation of images shot by citizen journalists, militant groups, and the state media and their recycling and appropriation by mainstream media outlets and artists? This also raises ethical and political questions about the production and circulation of images of violence: can one draw clear boundaries between militancy and art? Can these images intervene politically by providing a testimony to the horror? Or is circulating them catering to the audience's voyeuristic desire and driven by the logic of high media ratings and therefore more advertising income for the corporations? How ethical is it to recycle images of death and mutilation into artworks?

In the wake of the Syrian revolution, these became urgent questions. Abounaddara, the Syrian collective of anonymous self-taught filmmakers, has been engaged in emergency cinema by producing short documentaries since April 2011, aiming to reclaim the dignity of ordinary Syrians by countering both the images produced by the murderous regime and the international media. The collective is also influenced by the soviet filmmaker Dziga Vertov. Its name, Abounaddara – the man with glasses – is both a reference to how ordinary people are sometimes nicknamed according to their professions and an act of affiliation to the world republic of documentary cinema by paying tribute to Vertov who called himself the man with a camera.[4]

In a text published in April 2016 titled 'We Are Dying – Take Care of the Right to the Image', Abounaddara calls for a right to one's own image predicated on the notion of human dignity and the right to self-determination.[5] The collective issues a plea to stop the international media from continuously exploiting the representations of the Syrian people, particularly the bodies of killed Syrians for the interest of states and the profits of corporations. While doing so, Abounaddara draws attention once more to the media's unequal bestowal of human dignity. 'The shameless broadcasting of the bodies of slain Syrians,' they note, 'would be unthinkable if the victims were American, French or Belgian'.

ZO: You characterize the Palestinian revolution as inscribed in a Third-Worldist moment that amongst other things was defined by the de-centring of Europe. Part of this decentring entailed the troubling of the division of labour between the thinkers and the doers in the world. Can you dwell on what this blurring of division and internationalist solidarity meant in a moment of hope? And how does it compare with our present?

FB: In my work I develop Kristin Ross' insight that the Leftist moment of the 1960s and 1970s witnessed a de-centering of Europe that went beyond a prevalent division of labour: Europe provides the concepts (theory) and the rest of the world acts (revolution). Both theory and revolutionary practice were generated from the metropole's peripheries during that moment. The wretched of the Earth, as Ross puts it, were not only the doers, the third-world revolutionaries, but were also the thinkers such as Fanon, Guevara, Mao, Giap, and Cabral.

To compare this recent past of de-cantering Europe with our present, let's look at how the Syrian revolution is represented. The Syrians who rebelled against a dictator who inherited a republic from his despot-father are portrayed through the statist-security language of terrorism, the culturalist language of sectarianism, and the humanitarian language of refugees. What these three figures – the violent terrorist, the vengeful sectarian, and the victimized refugee – have in common is an evacuation of the political dimension of the struggle between a regime engaging in mass murder and citizens rebelling against it, despite all the regional and international interventions and internal societal divisions. You rarely hear of Syrian militant peasants or freedom fighters. Both these concepts were associated with the 1960s jargon of solidarity. Why? Because the Syrian revolutionaries have been narratively and visually excised from the domain of rational politics, either as 'madmen of religion and identity' or 'victims to be saved', and in both cases the negation of the political forecloses the possibility of solidarity.

Let me go back to the Abounaddara collective once more. Two minutes for Syria (2013), one of their poignant short films, begins with a burnt skull intensely gazing at us, the viewers.[6] You then hear the sound of camera shutters before seeing a man with a camera shooting a skull inside a glass case at a museum. A group of people walk around. They chat, smile and take pictures as they admire the exhibited skulls, which include the names of the people they belonged to, their age at the time of death, a number, and a description of their action. A close up shows one of the exhibited skulls with an inscription on its forehead: 'Assassin du Colonel'. As the group leaves the room you hear another loud sound. This time around it is not the sound of camera shutters but of the museum door – which eerily resembles gunshots – slammed shut after they exit the room. Two central captions then appear on the screen: 'STOP the Spectacle' and 'There is another way you can help the Syrian people'.

This very short movie shot at the anthropological Musée de L'homme in Paris is a testimony to, and a call to stop, the deficit of solidarity with the Syrian people. It reverses the direction of the gaze. Those subjects of a sovereign gaze who stroll around safely in a metropolitan museum gazing at a doubly objectified human death – both through the exhibited skull and its classification 'Assassin' – become the objects of the viewers gaze.

There is more to this film though. Its appeal to stop the spectacle ties our present with colonial historical, scientific, anthropological and cinemantic genealogies. In an interview, Charif Kiwan, the cinematic collective's spokesperson, mentioned that the first Syrian character depicted in film was represented as a fanatic.[7] The Lumière Brothers, shot a film in 1897 about the stabbing to death of General Kléber (1800), the head of Napoleon's occupying troops in Cairo, by Suleiman al-Halabi, an Syrian Azhari student.[8]> According to Kiwan, Al-Halabi was clean-shaven in real life but had a beard in the Lumière Brothers' representation. After Al-Halabi was caught he was severely tortured and sentenced to death by impalement. For years his skull would be shown to French medical students as evidence of crime and fanaticism and later exhibited at the Musée de L'Homme with 'fanatic' written on it. Was Al-Halabi's assassination of Kléber an anti-colonial act of resistance or one of fanaticism? The cinematic, scientific and anthropological coding of Al-Halabi's deed and the fate of his skull reveals to us the thickness of the colonial history that was briefly interrupted in the 1960s and 1970s during that moment of theoretical and political decentring of Europe. Just compare for a minute the enlightened-fanatic binary with the May 1968 slogan 'Vietnam is in our factories', that sought to tie in anti-imperial struggle in the peripheries of the world and anti-capitalist struggle in its metropoles.

I am of course not fetishizing that era of internationalist solidarity, nor claiming that we should reclaim without any attention to the intricacies of our present those Leftist older languages of emancipation. One of the conundrums we face today is that critical languages have been appropriated by power. Anti-imperialism and secularism are deployed both by Arab and Leftist Western defenders of the Syrian regime who seek to bestow legitimacy on the dictator by depicting him as resisting American imperialism and religious fanaticism.

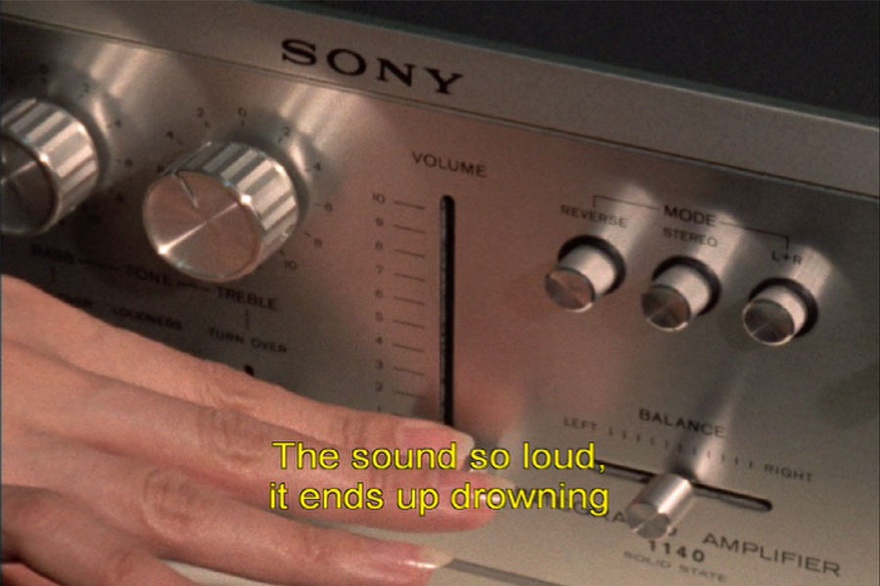

Moreover, if you look at the trajectories of Godard, Charara and Lazar you will get a sense of how critical they were of their past engagements after the ebbing of revolutionary tides. Charara was one of the first thinkers to draw attention to the importance of infra-national sectarian and regional solidarities in the wake of the Lebanese civil war (1975–1990). The idea of the people – the supposed subject and agent of revolution that would usher in the bright futures of equality – was not without its own internal contradictions. Godard and Miéville's masterpiece Ici et Ailleurs (1976) is an auto-critique of Godard's understanding of internationalist solidarity during his Dziga-Vertov years. The auto-critique is done by revisiting Godard's own politics of framing the Palestinian revolution through reworking the footage he had filmed a few months before Black September (1970) for a project commissioned by Fatah. The film that became Ici et Ailleurs was supposed to be called Jusqu'à la Victoire: Méthodes de Pensée et de Travail de la Révolution Palestinienne (Until Victory: Thinking and Working Methods of the Palestinian Revolution). Note that the title borrows part of Fatah's slogan, which is inscribed on its flag, 'Thawra hatta al-Nasr' (Revolution Until Victory) while the subtitle highlights both prongs of the Marxist tradition: theory and practice. Towards the end of the film in the voiceover he says:

We did what many others were doing. We made images and we turned the volume up too high. With any image: Vietnam. Always the same sound, always too loud, Prague, Montevideo. May 1968 in France, Italy. Chinese Cultural Revolution. Strikes in Poland, torture in Spain, Ireland, Portugal, Chile, Palestine. The sound so loud that it ended up drowning out the voice that it wanted to get out of the image.

Our world is increasingly interconnected by the movement of humans as migrants and refugees; the circulation of capital, commodities, and images; global military and humanitarian interventions; as well as climate change. In reaction to this increased interconnectedness we are witnessing at times the erection of nationalist and racist walls, the recycling of civilizational discourses and the promotion of a siege mentality. In revisiting the 1960s Leftist internationalism today, I am certainly not after recommending past answers to new questions. Rather, I hope to breach the culturalist walls of exclusion and recapture the political ethos animating the articulation of a common, interconnected world.

[1] 'Palestine at/without the Museum: Loss, Metaphor and Emancipation,' MACBA website, www.macba.cat/en/palestine-at-without-the-museum.

[2] Kristin Ross, May '68 and its Afterlives. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002).

[3] Boris Groys, 'Under the Gaze of Theory,' e-flux 5 (2012), www.e-flux.com/journal/under-the-gaze-of-theory.

[4] See www.abounaddara.com.

[5] Abounaddara, 'We Are Dying -Take Care of the Right to the Image!' Zeit Online, 30 April 2016, www.zeit.de/politik/ausland/2016-04/syria-victims-images-personal-rights-dignity-filmmakers-abounaddara.

[7] Moustafa Bayoumi, 'The Civil War in Syria Is Invisible-But This Anonymous Film Collective Is Changing That,' http://www.thenation.com/article/the-civil-war-in-syria-is-invisible-but-this-anonymous-film-collective-is-changing-that/.

[8] At 14.30 minutes www.youtube.com/watch?v=dLodGi6hyVk.