Interviews

Politics in Practice

Younes Bouadi in conversation with Stephanie Bailey

Younes Bouadi is Head of Production and Research at Studio Jonas Staal. The studio runs an artistic and political organization called the New World Summit, for which Bouadi recently oversaw the construction of a parliament building in Rojava at the invitation of the Democratic Self-Administration of Rojava. Bouadi's journey into the heart of art and propaganda began in his father's Moroccan restaurant business in the Netherlands, where Bouadi – then a high school student – worked on the weekends. He followed various paths, including finance and politics – he worked on John Kerry's 2004 presidential campaign in the United States – before ultimately deciding to move to Amsterdam to pursue a degree in art history, philosophy, and religious studies, where he worked on his first major research project, Khaled Hourani's Picasso in Palestine.

Stephanie Bailey: I wanted to start with what you call your first real production job travelling around Libya without a guide before 2011, during which you decided to work in the arts.

Younes Bouadi: Libya was part of a year-long travel I took through Europe, the Mediterranean, and North Africa. The trip solidified the path I wanted to take, and my time in Libya in particular helped me test and develop my skills in production. Getting into Libya and travelling without the required government guide was, in many ways, my first real production job as it was related to the intricacies of dealing with complex international border crossings and logistical issues such as imports and exports. This was before everything happened in 2011, and at the time you could only travel inside the country if you had a guide from the government; but we wanted to travel freely. This took me several months to arrange. After Libya, I travelled through to Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Turkey, and Lebanon, and then Eastern Europe.

During my travels, I realized that art was the field I wanted to work in. The bureaucratic and patriarchal hierarchies so present in the financial world did not appeal to me, and while I enjoyed politics, it didn't feel like the right fit either. Moving into culture as a professional shift allowed me to take many of the things I learned from both finance and politics into a working environment that enabled me to work in a positive way with a supportive team. In many ways, my work in production connected to my previous work in finance and politics, especially in finding those economic avenues in between art and politics where cultural capital can play so many roles. There has been a lot of overlap with all of these parts of my background, and this has come in handy moving forward as a producer.

SB: After your travels, you went on to study art history, philosophy, and religious studies at the University of Amsterdam, during which time you joined the Picasso in Palestine project.

YB: I decided to study art history, philosophy, and religious studies because I was very interested in the role of contemporary art in both its use as a tool for propaganda and its historical relationship with religion. There seemed to be a lack of attention paid to these relationships within each of these studies on their own, so I combined them in order to delve further. I also feel that if you want to understand art, you need a theoretical angle; so studying philosophy in addition to art history seemed like a logical step. Personally, I find it almost impossible to understand modern notions of contemporary art without some basic philosophical knowledge of Hegel or Marx, or even earlier thinkers like Augustine, who had this idea that art should be an investigational tool.

This combination of subjects made the Picasso in Palestine project especially interesting for me, as it crossed back and forth between all three subjects. Picasso in Palestine (2011) resulted from the Middle East Summit held in 2008 at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, the Netherlands, and entailed the displacement of Pablo Picasso's Buste de femme (1943) from the Van Abbemuseum to the International Academy of Art Palestine (IAAP). I got involved because Charles Esche, the director of the Van Abbemuseum, was one of the guest lecturers at the University of Amsterdam during my Master's program, in 2011.

SB: What was your research focus at the time?

YB: My research concerned art that uses the literal movement of objects through ideology and bureaucracy in order to examine – and critique – existing systems from an intellectual perspective. Art objects are embedded in material and ideological networks that shape them. They can also, however, reorder these networks in turn. There are, for example, always actors with an interest in making an object move to a different context, both literally and figuratively, as was the case in the Picasso in Palestine project. What is it that creates possibilities unseen before? How objects and ideas interact and change the framework of the possible is what has always interested me.

I wrote a proposal to travel with the delegation that would bring the painting to Palestine, which was accepted. The paper that came out of the project discussed the meaning of the displacement of arts objects in the context of this particular Picasso, Buste de femme, moving from the Van Abbemuseum to the IAAP in Ramallah, in relation to other works that involved moving material objects, such as the MOMA's A Modern Procession by Francis Alÿs,and Jonas Staal's Bomb Wreck Jewellery.I was interested in the effect the physical relocation of an (art) object has on its environment as well as what this relocation itself brings to the fore. The bureaucracy involved in moving an object is not a-political or unideological and it is by studying the particular relocation of specific objects that you can lay these often obscured ideologies bare. This is, of course, elaborated on in my paper, Picasso in Palestine: Displaced Art and the Borders of Community.

The background of the IAAP was in itself interesting to me, for many reasons. For example, – in 2006, after the first the democratic elections in Palestine, Hamas came to power, and even though Hamas was democratically elected, they could not be supported by states due to various treaties. One of those states was Norway, which has a long history of international diplomacy and peace building. Norway had to freeze all funding to projects that were taking place in Palestine. A large portion of these frozen funds were left suspended with no new projects, and my research also examined this suspension process as well as the artists who began lobbying for these funds. Eventually, the funds left in limbo were redirected to diplomacy through cultural means by supporting the initiation of the International Art Academy in Palestine.

Coincidentally, Norway still has a role in my work – the upcoming New World Embassy: Rojava, put on by the Democratic Self-Administration of Rojava together with Studio Jonas Staal, will take place in Oslo's City Hall the last weekend of November.

SB: Then you became involved with the New World Summit.

YB: Yes. I first met artist Jonas Staal in 2007 during the public intervention, Plastering the Dutch Constitution (Article 1), that he developed with philosopher Vincent W.J. van Gerven Oei, and continued to follow his work. In 2011, I participated in Social Experiment, a three-day training program where Jonas and four other artists, Klaas van Gorkum, Iratxe Jaio, Wouter Osterholt, and Elke Uitentuis, hired privatized police trainers – mostly former police officers – from a private security firm that teaches police officers how to be police officers. The artists hired two trainers to instruct artists, students, and activists in interrogation techniques as well as how to deal with violence.

Social Experiment actually took place a few weeks before the Occupy movement began in Amsterdam, and the group that took part in Social Experiment became part of Amsterdam's Occupy movement. During this time, I heard about the New World Summit and asked Jonas if I could research it, since our interests and backgrounds in art and propaganda overlapped a great deal. Instead, he asked me to produce it, and this led to our first collaborative effort.

Since then, we have worked together on many other projects, and were joined by Renée In der Maur in 2012, who has contributed much in terms of growing the studio. Projects we have presented as Studio Jonas Staal include all five New World Summits, and five New World Academy sessions – the more research and teaching focused branch of the New World Summit – which we have established together with our partners at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht.

SB: How did you go about producing the first Summit?

YB: Our initial approach was basically cold calling every organization on EU and US lists of designated terrorist organizations. We researched all the blacklisted organizations on the lists provided by the EU and US, and sent them official invitations to participate in the summit. We actually used US and EU government policy papers – there was a particular one from the US House of Representatives Subcommittee on Europe, Adding Hezbollah to the EU Terrorist List, which gave an in depth overview of how the terrorist lists in the EU are determined in practice – to help us understand the processes that surround listing and delisting terrorist groups. But of course this was not necessarily the most effective method, as we were not yet established and these groups had no idea who we were and whether they could trust us.

As part of the research, I attended various events and gatherings, and a turning point came at a conference at the University of Hamburg in 2012 which discussed critiques on current capitalist systems and alternatives including self-governance in the context of the Kurdish struggle for self-determination. The Kurdish revolutionary movement, like many organizations, have a long history of being blacklisted by those who see Kurdish agitations for self-determination as a threat to the current world order. This was my first real encounter with individuals in these organizations, as the conference included many speakers from movements that have similar progressive and left-leaning ideologies. While the speakers were not listed as terrorists, many of the organizations they represented or spoke about in solidarity to have faced ongoing anti-terror legislation. There were, for example, members of the outlawed Basque political party Sortu and people who spoke about the Zapatista movement in Mexico. Here, I met many speakers and participants, some of whom would go on to join us in the New World Summit, including Fadile Yildirim, a representative of the Kurdish Women's Movement, and Jon Andoni Lekue, at that time a representative of the Basque independence movement. Following that, I started to contact lawyers, and Nancy Hollander was the first to reply to my invitation.

From the very beginning, we had to also deal with the political and practical impact of what it means to work with individuals being labelled as a terrorist or as a member of a terrorist organization. We had to figure out how to work around the obvious political implications of working with those labelled as such. Finding a grey area of who is able and willing to represent these organizations publicly has been a challenging balance. Negotiators and legal representatives, who occupy much of this grey zone, have played a large role, especially because of travel restrictions placed on individuals identified as members of many of these groups, something that is not the case for the lawyers of these organizations.

SB: Nancy Hollander, a public attorney based in Albuquerque, has been one of the key figures to really interrogate the term 'terrorist' from the first summit of 2012, when she attended as counsel for two prisoners at Guantanamo Bay and members of the Holy Land Foundation, the latter having been placed on the terror watch list as a result of its charitable activities, which were perceived as benefiting organizations linked to Hamas. Her participation highlighted the ambiguity by which terminology is both deployed and defined: crudely put, one man's terrorism is another man's resistance movement.

Hollander also brought a perspective on the neutrality that the law offers when thinking about the way terminology is defined and deployed in objectively constitutional terms. For Hollander, the crucial importance is that everyone is treated equally under the law. This enables Hollander to challenge the way terminology is manipulated, often by the state, and how such manipulations justify unfair or unwarranted incarcerations, such as those in Guantanamo Bay.

How has your understanding of the terms 'terrorist' and 'terrorism' developed through your work with the Summit?

YB: I think Albuquerque is the place where much of the fallout of the American empire and the periphery of America come across clearly, given the grey zones and the borders that intersect there. It is here that Nancy works, an east coast New York lawyer and kind of grey zone herself, who became part of the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. from the very beginning, before joining Freedman and Boyd in Albuquerque in 1980. As someone who has devoted her entire life to issues surrounding legal grey zones, she was drawn to the New World Summit as a natural ally. In her experience of handling cases for clients who must deal with the realities of living precarious lives in a state of exception, Nancy was able to help us bridge the gap between the theoretical, where the arts and humanities often get stuck, and the practical, which is often the only side the law considers. While she, a long-practicing and extremely successful lawyer, has never studied the writings of Agamben or Judith Butler, which are held in such high regard in the theoretical world of the humanities and arts, she has clearly had great success implementing the intricacies of theoretical law on a practical level.

I see the term 'terrorist' as a strategic tool of those in conventional forms of power. I mean this in the sense that the terminology can be, and often is, used to delegitimize struggles against colonial and imperial histories, occupations, and imposed power. There is also a certain asymmetry between recognized state powers and non-state actors. Non-state actors often use guerrilla tactics – small, quick movements and strikes – where of course states can employ full military operations with all of the abilities and power that implies. But in looking at the UN Charter and legal realities surrounding self-determination, there is nothing illegal about striving for self-determination and resisting oppressive powers through armed struggle, even offensively. War is not illegal, but regulations on war – like those of the Geneva Conventions – are still applied.

The point of labelling an individual or group as 'terrorist' is to take people outside the existing juridical framework. This can take the form of 'non-enemy combatants', 'terrorists', or other terms used to avoid implementing basic human rights, or following laws set by the Geneva Conventions or other international legal frameworks designed to govern warfare. The term terrorist is a political and strategic tool. This does not mean there is no such thing as an act of terror. Of course there are those, both state and non-state actors, who commit crimes with the direct intention of causing terror for political aims among civilian populations. But the existing legal framework should be able to handle these cases, without needing special categories for extra-legal means of prosecuting such crimes.

Terrorist designations are also used in geopolitical machinations. Existing state powers use designated terrorist organizations to create proxies to serve their own goals. These groups often accept these roles as proxies because they can further their causes this way, using the implications of the label as a way to justify or legitimize their cause, which is often against state power. The result is a negative symbiosis that reinforces the asymmetrical worldview of state versus non-state, while allowing both sides to use the other in order to further their own goals.

SB: This brings us to the organizational and spatial design of each New World Summit, which reflects a highly constructed format that enables a greater horizontality among various factions and groups. Could you talk about the design of each summit from your perspective?

YB: The conversations happened between Jonas, myself, and Paul Kuipers, who is the architectural collaborator in all the summits so far. My own focus was on devising and maintaining the budget and conducting material research as well as overseeing the actual production.

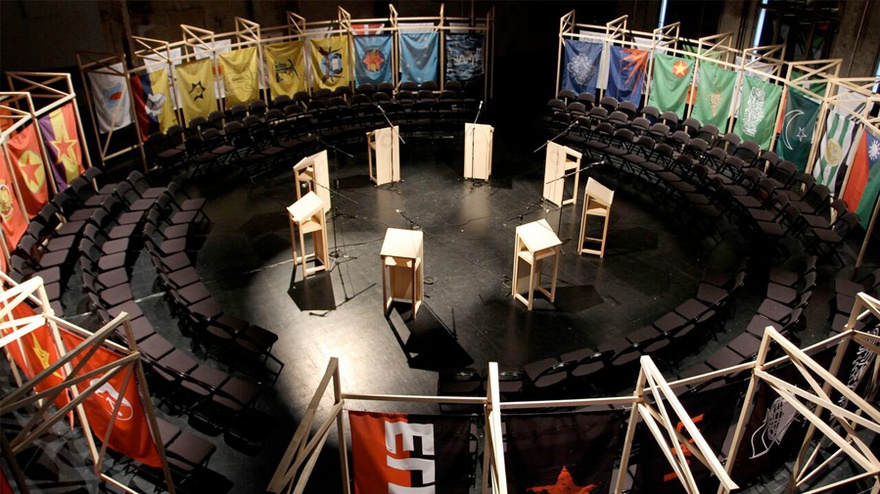

There is a method to the madness in the composition of the summit. In terms of spatial design, for the first Berlin summit we worked with chairs set up in a centered round with the speakers in the middle. This broke the standard presentation style of the audience watching speakers on a stage. The second summit in Leiden was more like a case study. We still used chairs, but we put everyone behind a massive rectangular lectern instead of using individual lecterns for the speakers, to break down another barrier of who was a speaker and who was an audience member, and to explore what that divide, or lack thereof, meant. During the summit itself we explored the different layers that create the divide between so-called terrorists and "regular" citizens by inviting a lawyer, judge, public prosecutor, politician and academic. Then, in Brussels, we decided to make the move from chairs to benches, in order to build a more communal feeling and reject the liberal and individualistic nature of separate chairs.

Benches became an important architectural element of the summit space. By having a fixed amount of seating that remains somewhat flexible, the social dynamics of the space become more determined. There's also a sense of positive presence in this shift; if you look out into an audience and there are empty chairs, you feel that absence. But if you look out and see people scattered on benches, you feel the presence of those people.

SB: Speaking of capitalist systems and benefit, could you talk about the contradictions inherent in the funding behind the New World Summit? These became apparent when you went into Rojava and built a parliament building there in 2014 after responding to an invitation from the Democratic Self-Administration of Rojava. This was the NWS's first permanent infrastructure in a non-western setting: the moment the New World Summit, essentially a western, state-funded organization, stopped acting as a neutral mediator and began acting within and for a very specific history.

YB: The funding we get comes from the state, whether directly or indirectly, which is the same body that is labelling these groups as terrorists. The idea of the state in these contexts can even be a contradiction, especially in cases like Rojava, where the ideology of the movement rejects the very premise of the state. There is also the danger, with us doing the work, of whitewashing the suppression coming from the state. Thirdly, I would say that there is a strong contradiction in being part of a world where anyone buying these works has an excess of money that reflects the systems many of these organizations are struggling against. Finally, because we operate not only in an activist system but also a cultural system, we create cultural capital. We have to walk a fine line between not taking more than we give in terms of what everyone gets out of our work.

We have these conversations clearly with our partners, in order to be as open and honest as possible. When you do the work that we do, it's impossible to completely avoid working with the powers that be and the existing systems. But we go into our work looking for ways to make gains for everyone we work with.

SB: How did the Rojava project begin?

YB: The summit in Rojava was never actually planned. It came out of the inaugural conference of the fifth New World Academy, 'Stateless Democracy: The Revolution in Rojava Kurdistan'. Jonas received the official invitation to travel to Rojava, from PYD Co-Chair Salih Muslim after interviewing him in the Netherlands, and the subsequent commission for the parliament came from Deputy Chair of the Committee of Foreign Affairs Amina Osse once we were there on location. But getting the project to Rojava was quite complicated and funding was also a huge challenge. Eventually we found a way to finance the preliminary research to the project with the help of our long-time partner and co-establisher of the New World Academy, BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. The first piece of the project, our travel there, was made possible by BAK's collaboration in the sale of New World Academy exhibition model to Centraal Museum Utrecht. This is a good example of the intricacies and contradictions that allow our work to proceed. We also had a lot of support from the Van Abbemuseum, which purchased the maquette of the Rojava project for their collection in order to make the actual construction process a reality.

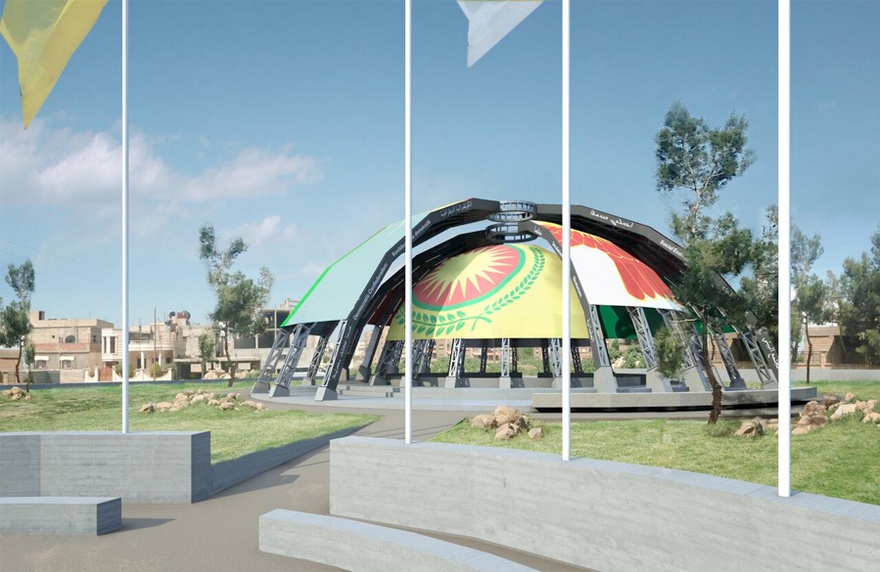

When we went to Rojava for the first time in December 2014, our discussions were influenced by the fact that the Kurdish movement had been involved with the New World Summit from the very first edition, when I met them at the conference in Hamburg, and they were familiar with the work we were doing. At one point during this first travel to the region, the Democratic Self-Administration formally invited us to host the summit there in a permanent structure that we would design and build, which would become a parliament building.

SB: Was this a tactical move in terms of building the legitimacy of the Democratic Self-Administration of Rojava, while enabling a certain level of protection by engaging with a western institution during a period of war?

YB: First and foremost, the Self-Administration wanted to participate in an international and cultural exchange, while contributing to their own civil infrastructure in a concrete way. Of course, there is also a political reality attached to this project, in bringing about further exchange and new forms of cultural recognition. But the investment in art and culture, throughout the region, is substantial and considered fundamental for a new civil society to come into being. They wanted to create an exchange with us and our cultural network.

Rojava had hosted international delegations before, but they predominantly consisted of journalists, politicians, and radical activists. This collaboration was also a good opportunity for them to host another type of international delegation. That being said, the construction is of course also a true parliament and it will be used as a functional building, meant for local organizations in Dêrik, demonstrations, and international meetings.

The reason our work resonated with the Self-Administration is that culture and art speaks to the core tenant of self-defense that underlines democratic confederalism. The revolutionary movement views the pillar of self-defense not from a military perspective, but from a more preservationist approach. If there is no art, culture, language, or people, then there is nothing to defend with military force. Therefore, defending and building up the other aspects of society, to which the New World Summit hopes to contribute as well, is incredibly important to the foundational ideals of Rojava. They invited us to collaborate as equal partners and made an investment equal to that of our Western partners themselves – a worthwhile decision for them despite the ongoing war and scarcity of resources.

SB: Could you talk about the practical experience of producing the summit and constructing the parliament?

YB: Once we received the invitation, I started researching what materials and techniques were being used in contemporary constructions in Rojava and the surrounding region so that we didn't go with a western blueprint. It was more about seeing what was possible, and thinking about a more ideological way to implement the project. We went to the region for the second time in April 2015, and from the moment we crossed the border we spent hours in meetings with the local city council and representatives of the city's communes as well as government representatives of the Democratic Self-Administration of Rojava. Amina Osse was the main voice in bringing the project forward and building support – we provided sketches and proposals – and the local council asked how many square meters we would need. I said approximately 2500 square meters. There is still a lot of space for development in the city, and once Amina, as the commissioner of the project, had built a base of support, the council was quick in finding several options for a location.

I can say the process as a whole was incredibly challenging. Rojava is a region in conflict; the situation was changing daily. When we started the construction plans in April 2015, for instance, the situation was completely different than when I returned four months later, and this affected the budget. The biggest change was that Kobanî and Cizîrê were reunited with one another, but Kobanî had been completely destroyed. So all capacity for building – machinery, qualified workers – was going to Kobanî. We had another production meeting with several engineers and architects that were assigned by the local city council to the project during that month, and the questions were about who would actually build the parliament, who the contractors would be, what materials would be used, and who would actually buy them.

I found myself in a situation where I needed to learn how the system worked, so to get the project started I learned more about how Rojava operates. It was then that I started to understand the local dynamics in greater detail and see how such a small, precarious government with often limited resources was able to function in practice: by building working relationships of trust and loyalty with individuals and groups throughout the region.

Of course a long term project like this is difficult in a reality where changes are quick and urgent. Materials and equipment were scarce to begin with, and when they were needed for the self-defense of the region, we of course would not lay claim to them. The defense of the region against attacks of ISIS had of course priority over everything. We did our best to overcome the paradox of coming in as an outside authority with a position of privilege working in a society which aspires to complete egalitarianism, and worked together with guides, translators, and local partners to work from within the system and with the local structures.

SB: How were the summit and parliament building received?

YB: The building process itself was slow, partly because we often couldn't get materials on site due to the changing situation and partly due to our inexperience with working in the system of Rojava. At one point it was clear that we had to postpone the summit taking place in the actual building, so then decided to restructure the event, finishing the building while organizing the conference alongside the construction.

Eventually, we decided to hold the conference at the local cultural center of Tev-Cand – it was staged in October 2015, during which we presented the parliament, which was still under construction. Staging the international conference in a conflict region was incredibly complicated. It was a miracle that we managed to navigate all of the obstacles in getting the delegation across the border to the conference. But once we managed that, things went much more smoothly. We split the delegation into smaller groups and each group visited the different organizations of Rojava, with guides and interpreters, such as the cultural centers, the women's organizations and, of course, the protection units. Following the visits, the summit itself went very nicely. We had a full house at the cultural center, and both the international and local speakers were very well received. While of course not everyone agreed on everything, we were able to have some very healthy dialogues about democratic confederalism, feminism, and Rojava in the wider international context.

The presentation of the building also went remarkably well. While it wasn't complete, it was finished up to a point where we could hold the opening ceremony inside, which was great. It was a very festive atmosphere, with the formality of the speeches and the actual 'ribbon cutting', so to speak, followed by a fantastic Kurdish dance party that involved everybody, from officials and foreign diplomats to YPJ and YPG members, to local kids and families.

SB: How did this experience feed into your personal research?

YB: This definitely relates to what I said about needing philosophy to understand art. If you look at Hegel and history, you really are in history at that moment. You're on the edge, and not just from the New World Summit's perspective. From my own very simple analysis of what is happening in Syria, the situation there has its roots in how the historical empires and other imposed powers in the region are being realigned. Of course, there are many more layers of complexity to it, but historical forces that have been acting for at least 1000 or 2000 years are now realizing themselves in Syria. Like tectonic plates, all the different politics of this region are colliding with each other. Working there, I was very much aware of being present in this historical moment, and how these forces influenced the project, whether directly or indirectly.

SB: What did you – both as an individual and as a member of the New World Summit – take from your work in and with Rojava?

YB: Personally, I was there for almost four months, and out of that time I spent one and a half months on my own. At the heart of that is having to operate in a system that is not your own, which of course raises colonial connotations. At the same time, this was the most important project we had ever done, and there was a lot weighing on it. It was also this incredible environment to be in. The people in Rojava have been struggling for their existence since the 1980s, but still they are so positive and generous it's amazing. So many of them have spent months in prison or been tortured or have lost their lives, and it really put things into perspective and made any investment on my part feel completely irrelevant.

In terms of what we gained from this as the New World Summit, we were able to engage with an movement that has been organizing for the last 20 to 30 years, and has been actively building its own infrastructure. Of course, a lot of socially engaged art practices try to tackle this issue between the project realization and the strategy. To change something and to realize a project like this you need longevity, commitment, determination, and the kind of horizons you have to have and the kinds of alliances and partners that you have to make to get people involved – this is something that we really got out of it. For us, we got to create new solidarity together through the construction of a permanent parliament building, which acted as a symbol of commitment. We were able to realize possibilities in an active attempt at aligning forces.

But what I really took away from my time there – as both an individual and in my capacity at the studio alongside Jonas and Renée – is just how intense and long the struggle for true structural change is, and just how far we still have to go. But building up these long term relationships and ensuring our dedication to really enacting these systemic and structural changes can only be possible if we have partners willing to do the same. This is why our long term partners and collaborators, such as Maria Hlavajova and Arjan van Meeuwen at BAK, and Charles Esche at the Van Abbemuseum, continue to play such important roles in our work as we all move forward together on these projects.

SB: Where does the New World Summit go from here?

YB: Coming up we have the New World Embassy at the Oslo Architecture Triennale in collaboration with KORO Public Art Norway / URO. This will be a two-day temporary embassy – held on 26 and 27 November – where representatives from Rojava will debate and discuss topics with international diplomats, academics, and activists, all at the Oslo City Hall where the Nobel Peace Prize is presented. Following that, we will hopefully be able to return to Rojava next spring in order to finish construction, and then officially open the parliament with ceremonies both there and here in the Netherlands.