Interviews

The Shortest Length Between Two Points

Slavs and Tatars in conversation with Franz Thalmair

Slavs and Tatars is a collective, or 'faction of polemics and intimacies', founded in 2005 and dedicated to the area east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China. After devoting the past five years to two cycles of work, including a celebration of complexity in the Caucasus (Kidnapping Mountains, Molla Nasreddin, Hymns of No Resistance) and the unlikely common heritage between Poland and Iran (Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi'ite Showbiz, 79.89.09, A Monobrow Manifesto), Slavs and Tatars have begun work on their third cycle, The Faculty of Substitution, on mystical protest and the revolutionary role of the sacred and syncretic. The new cycle of work includes contributions to group exhibitions – Reverse Joy at the GfZK, Leipzig, PrayWay at the New Museum Triennial and Régions d'Être at the Asia Pacific Triennial, as well as solo engagements at the Secession, Vienna (Not Moscow Not Mecca); Moravia Gallery, Brno (Khhhhhhh); MoMA, New York (Beyonsense), and the Künstlerhaus Stuttgart. The following is an interview with Slavs and Tatars conducted by Secession curator Franz Thalmair on the occasion of their exhibition Not Moscow Not Mecca in Vienna and for the accompanying publication for the show, which discusses their new cycle of work, their concept of transliteration and transubstantiation and the role of humour in art practice.

Franz Thalmair: What comes to your mind when you hear the term 'myth'?

Slavs and Tatars: The fragrance greeting us each and every morning.

FT: How do you integrate spirituality into your daily lives as multicultural polyglots with mobile computing devices, travelling from airport to airport?

S&T: We try to make the spiritual as concrete as possible. After all, the etymology of concrete is 'con+crescere', to grow together, and that is perhaps the best way to distill the nebulous and complex motivation behind any collective. Henry Corbin, the great scholar of Shi'a mysticism and specialist on the Illuminationist philosopher Suhrawardi (not to mention the first person to translate Martin Heidegger's Sein und Zeit into French), writes about 'hamdami', or 'con-spiration', the 'breathing together' of the sensual and the spiritual that is the hallmark of the Sufi scholar Ibn al-Arabi.

FT: As a geographically dispersed collective, how do you organize yourselves?

S&T: We work quite a lot via Skype. Otherwise, we meet roughly once a month in person for various exhibition openings as well as research assignments or speaking engagements and then extend these stays to work amongst ourselves. In some sense, we are extending the word opening to include not just the audience, but also us. As opposed to the traditional dynamic, where an exhibition opening is a moment of commemoration, or for relaxing and reflecting, we use it as a platform to address an existing cycle of work or as a point of departure towards something.

FT: Your academic and professional backgrounds are in literature and typography/design. What does that mean for your work as Slavs and Tatars?

S&T: Actually, our backgrounds are in philosophy, fine arts, and graphic design. Comparative Literature is a euphemism used in Anglo-American universities for all the post-war Continental philosophy that traditional English and American philosophy departments were not willing to integrate, and which then found shelter in literature departments. This means we are heavily invested in discourse.

FT: Speaking of etymology, as a key field in the study of languages and in combination with your interest in philosophy and discourse: Could your exhibition at the Secession – as part of your new cycle of work entitled The Faculty of Substitution – be described as a research trip into the history of the term substitution as a mystical practice? What is substitution?

S&T: Today, we not only need intellectual acrobatics but metaphysical ones: substitution requires us to cultivate the agility, coordination, and balance necessary to tell one tale through another, to adopt the innermost thoughts, experiences, beliefs, and sensations of others as our own, in an effort to challenge the very notion of distance as the shortest length between two points. In terms of our practice: to understand contemporary Iran, we look at Poland and Solidarność (Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi'ite Showbiz); to grasp the nature of political agency in the 21st century, we study Muharram and the 1300-year-old Shiite ritual of perpetual protest (Reverse Joy); to demystify Islam, we turn to Communism (Not Moscow Not Rome, Secession); and it is through mysticism that we intend to address modernity (Beyonsense, MoMA).

For The Faculty of Substitution, we are looking at, among other things, the notion of mystical substitution – also known as sacred hospitality or the transfer to ourselves of the sufferings of others – a notion one finds across such disparate figures as Mansur al-Hallâj, Joris-Karl Huysmans, and Louis Massignon. These individuals believed that it is only through the embrace of something outside oneself that one can achieve self-knowledge.

FT: To what extent do you make your research results viable and practicable for the present moment?

S&T: It is crucial to resuscitate the historical. We don't know of a better way to demonstrate its relevance to people who might otherwise consider our interest in a region or its history arcane or irrelevant. We use the word 'resuscitation' for a reason: its sensuality, the idea of breathing life into a subject (by placing one's lips on the mouth of the area of study, if you will) points to an affective relationship with an idea or a text. It was Michael Taussig who taught us many moons ago that the challenge of abstract and/or mystical concepts (the example he used was Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari's 'becoming imperceptible, becoming wolf') is not only to analytically understand its philosophical genealogy, but more importantly, to use it as a how-to guide, to live the ideas.

FT: To live the ideas means that your self-conception of being artists is a matter of personal, subjective, and experience-driven agency towards the world you live in and towards the worlds you come from. How do you link this practice with the art world? How does your experience manifest itself in the actual physical spaces of art?

S&T: Given that Slavs and Tatars began quite simply as a reading group, we try to maintain the spirit of sharing and exchange that is part and parcel of our origins – the act of reading together. Recently, we have taken to redeeming a space for contemplation, reflection, and exchange that is, contrary to what one would expect, often missing from the physical spaces of art. There is lots of talk about participation, outreach, and so on, but how often do we come across exhibition spaces where there's simply nowhere to sit?

Since the Sharjah Biennial, we have been increasingly interested in the notion of generosity, as much as a tactic as a concept. Our Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi'ite Showbiz featured 'takhts', or riverbeds (one of the few places to escape the otherwise scorching sun during the 10th Sharjah Biennial), where both Baluchi day-labourers and art-world types could relax, read, and engage with the unexpected common heritage linking Poland and Iran. In the otherwise unforgiving space of the New Museum, PrayWay allows visitors to sit on a souped-up hybrid of the 'rahlé' (a stand for holy books) and the riverbed.

FT: Coming back to what you said about the integration of Continental philosophy in Anglo-American universities: your working method of using ancient texts (in the broadest sense of all forms of cultural products) as a point of reference in generating new texts or in gathering knowledge about a certain fact is, without a doubt, comparative. What is the distinctive strength of comparative etymology as practiced by Slavs and Tatars?

S&T: Speaking, breathing, reading, dreaming in different languages is a kind of productive schizophrenia of sorts: we are very different people in Russian and in Polish, both Slavic, much less say than in French or English. So interdisciplinarity, the holy grail of academes and art schools alike, is an integral part of any comparative study – be it in linguistics or religion. Slavs and Tatars' ostensible contribution to comparative studies is the emphasis on mixing scales and registers previously considered incommensurate.

FT: Could your work be described as curatorial work?

S&T: Insofar as the term 'curatorial' means 'editorial', yes. Having said that – and despite a proclivity to work and think across disciplines – we are committed to maintaining the traditional division of labour between curators and artists. While art and the artist figure significantly in the curator's work, either as a point of departure – to explore a position or to tell a certain story – or as the result of this investigation, we look instead to history, linguistics, religion and geography to tell these stories.

FT: Could it be described as archival?

S&T: Perhaps we would prefer the word 'restorative'. Despite its recent critical renaissance or promiscuity (depending on where you stand), the word 'archival' still implies a dusty collection of documents and records and the aura that accompanies this material. We believe it is equally important to disrespect one's sources as to respect them. That is, to reconfigure, resituate, reinterpret, and collide the archival material with the aim of making it relevant and urgent – not just to the specialist in the field, nor just the intellectual, but also to the layperson who might not otherwise be interested.

FT: The essays, statements, and project descriptions that Slavs and Tatars publish repeatedly seem to suggest a kind of 'not only, but also' attitude in your work. Is this one of the characteristics of the anti-modern condition that you refer to?

S&T: No, this maximalism stems more from a regional position and has less to do with the anti-modern per se. Without falling entirely into essentialist ethnocentrism, it is safe to say that Slavs, Caucasians, and Central Asians are a bit grander, less frugal, than Anglos, Teutons, and Gauls. We don't split the dinner bill 12 different ways.

In his book Les Antimodernes (Gallimard, 2005), Antoine Compagnon, Professor of French at Columbia University and the Collège de France in Paris, describes the true modernists not as the Utopianists who only look forward (such as Vladimir Mayakovsky and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti) but rather as the 'anti-modernists', those somewhat conflicted visionaries deeply affected by the passing of the premodern age. As Jean-Paul Sartre said of Charles Baudelaire: 'Those who go forward, but with an eye in the rearview mirror'. Walter Benjamin uses a similar trope with his Angel of History, thrust forward with her back to the future and facing the past – similarly to the Malagasy language, which, contrary to most western, positivist conceptions of time, uses words such as 'behind' to describe the future and 'in front' to convey the past.

FT: One of your statements is, 'Nous sommes les antimodernes, that is, we prefer the rearguard to the avant-garde'. To what extent is your work linked to the discourse surrounding modernity in contemporary artistic practice?

S&T: First of all, it would be important to ask: Whose modernity? Yes, we are critical of the traditional understanding of a modernity that broke with the past and attempted to create a New Man, be it 'homo sovieticus' or 'homo liberalus'. In doing so, it whitewashed the spiritual or numinous and led to such counterintuitive behavior as quarantining the elderly and celebrating youth. To some degree, our work tries to come to grips with the complex role of the stranger (and the stranger's region) as an agent of attraction and repulsion in modernity: a simultaneous source of fear, exclusion and enticement, as Zygmunt Bauman discusses in his Modernity and Ambivalence (1990) and Modernity and The Holocaust (1989).

FT: Would you say your work is reactionary or even unprogressive?

S&T: In today's amnesiac world, even to acknowledge that there exist basic tenets of wisdom – much less strive to preserve them – is perhaps conservative but not reactionary. On the contrary, it is progressive. The older we get, the more we soften our views on the very Texan phrase which only a decade ago repulsed us: 'If it ain't broke, don't fix it'.

FT: Visually, your work tends to highlight the beauty inherent in folklore and popular culture in the east and in the west – the beauty of its forms, the beauty of its speech, the beauty of its tradition, a beauty deriving from something fundamentally combinative. Is this emphasis on beauty a form of cultural criticism? What are your strategies in this respect, how does it work?

S&T: Perhaps it is. We are suspicious of the notion that a single century can or should entirely overturn several centuries of understanding about culture. For some reason, it is inherently more fashionable, accepted, and widespread for art to dismiss beauty as dépassé or out of fashion and in turn focus more on the ugly, the destructive, the distraught. This does not mean we wear rose-coloured glasses: it is important to highlight that which is uncomfortable, but it is far easier today to make interesting work that is dirty and dark than to make work that is somehow enlightening, or fun. We strive to be in the camp of the latter, never mind the risks.

Take humour, for example. We think making people laugh is perhaps one of the most important and, in some sense, most generous things one can do. But just because the work is fun does not mean it need be silly or light. That's the challenge: to occupy both ends of a spectrum often, and mistakenly, considered to be incommensurate. To be fun and serious, cheerful and critical, at the same time.

FT: What do you say to people calling your work 'romantic'?

S&T: 'Would you like to meet for a cup of tea?'

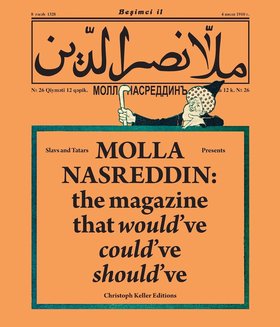

FT: One of the many strategies you use in your work is the conflation of cultural phenomena. When talking about Molla Nasreddin: the magazine that would've, could've, should've (2011), one of your recent book projects, you mentioned that conflation is an important strategy, practiced from the thirteenth to the twenty-first century – from Molla Nasreddin to Ali G. Where do you see the main points of contact between the witty Molla Nasreddin and the rather crude Ali G, between the cultural strategies of the thirteenth to the twenty-first century? What are the fields of merging and blending, what does a blend of Molla and Ali G make?

S&T: First, we consider comedy and, more generally, humour to be very fertile areas not so much for study as for practice. Ali G's line of questioning – positioning himself as an idiot – is not that far removed from Molla Nasreddin, the thirteenth century wise fool. The former's context and language are definitely cruder but it remains a very sophisticated comic device. By presenting himself as incorrigibly thick, he in fact reveals the arrogance and idiocy of his interviewed subjects.

Conflation wears many different disguises – creolization, mash-up, collision – each distinct but all essentially playing for the same team. The collision of different registers, different voices, different worlds, and different logics previously considered to be antithetical, incommensurate, or simply unable to exist in the same page, sentence, or space is crucial to our practice.

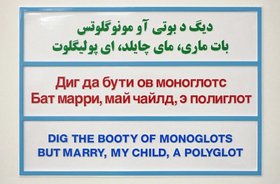

FT: Your work has a lot to do with translation or, as you term it, 'transliteration, a fat ugly cousin to translation' or a 'trashy, teenage sibling'. In comparison to the concept of translation, where a one-to-one relationship between two texts is not necessary, in linguistics, the term 'transliteration' means that a written text is transferred into another written text – respecting the form, shape and body as well as the character of the original. To what extent is this one-to-one relationship between languages, objects, and narrations relevant for your work at the Secession?

S&T: The work at the Secession is perhaps closer to an exercise in a 'transubstantiation' of sorts, not in a traditional Roman Catholic sense but a syncretic one. We are trying to address a set of issues by radically altering the form as the flesh, the corporality, which is traditionally associated with it. So in this sense, to take your definition, it's perhaps closer to translation than transliteration. In general, substitution is a more immanent concept for us than translation: it has a phenomenology, a being quite simply that translation seems to lack.

FT: In The Task of the Translator (1923), Walter Benjamin once used a metaphor to describe translation as a tangent that 'touches the original lightly and only at the infinitely small point of the sense, there upon pursuing its own course according to the laws of fidelity in the freedom of linguistic flux'. The crucial point about this statement is that fidelity and freedom do not come into conflict but are components of one and the same process. Does that apply to Slavs and Tatars with regard to fidelity to cultural identity and the freedom of its artistic reinterpretation?

S&T: Yes, we embrace this idea wholeheartedly: the freedom of linguistic flux is crucial to our work and to the understanding of the world around us, including that of identity. Again, what's interesting is that two notions often considered to be in tension – the steadfastness of fidelity versus the flux of freedom – are part of one and the same process. There's a saying that the Caucasus is a man whose body is without curves: this is often used to describe the headstrong, muscular will of mountain peoples. We try to round out this body and to moderate the tendency to see identity as brittle.

FT: In your exhibitions, you assemble not only ideas but cultural objects and artefacts which seem to have been collected on long journeys to ancient times and places. Do you agree with descriptions of your work as a contemporary, visual form of travel writing, one of the most common forms of literature in all cultures and at all times?

S&T: We never thought of it that way, but that is a compelling interpretation. Advances in technology have facilitated travel incredibly over the past century but this has not necessarily been accompanied by a proportionate increase in wisdom and understanding. In fact, the reverse is probably true.

FT: What comes to your mind when you hear the term 'folk'?

S&T: More radical than punk.

FT: And the term 'pop'?

S&T: Helps the medicine go down smoothly.

FT: Do you think that the fruits that you are presenting at the Secession, such as the pomegranate, the mulberry, the watermelon, or the sour cherry, provide vessels or containers for this kind of wisdom and understanding about cultures that are not so widely known in the west?

S&T: Speaking through the flora of a region forces us to think that much less anthropomorphically. There is an undeniable pleasure, a basic luxury that fruits offer as a comestible experience. The project at the Secession tries to translate this luxury into an agency or a platform to think about similarly basic luxuries – reading, thinking, the communal practice of faith – across this particular region.

FT: How does the outdoor installation, the two large hemispheric melons flanking the central staircase of the Secession, contribute to your exploration of 'a collective autobiography of the region of Central Asia'? How are these objects linked to the shrine-like installation inside the Secession?

S&T: Like the balloon in A Monobrow Manifesto, the watermelon is a fun, stupid medium and epiphenomenon through which we can tell much more complicated stories. It is a fruit of caricature par excellence: whether in its very graphic pattern (see the watermelon balls inside) or its associations with the fruit of the 'Other', the darkie, the immigrant, if you will. In the USA, the watermelon evokes racist stereotypes of African American culture; in Europe, its provenance and point of sale recall the immigrant, the Muslim, the Turk – essentially, those European fears. Finally, in Russia, it is linked with the Caucasus and the troubled rapport between the two.

In a no less important sense, the watermelons at the entrance to the Secession announce the arrival of spring and summer and the bountiful harvests of these seasons, a more literal take on the 'Ver Sacrum' on the facade. Together with the syncretic shrine inside, the fruits are an invitation to engage with the exhibition affectively and not just cerebrally.

FT: You deliberately play with the ambiguity of words, with their mis-, re-, or new interpretation and with accidental meanings that may or may not arise. Would you say that wordplay is a domesticated, tamed form of misunderstanding – a deliberate one, as it is played out by Slavs and Tatars in artworks such as When in Rome, To Mountain Minorities (Kidnapping Mountains), or Nations?

S&T: On the one hand, these performative acts on the text are part of the research itself: they are not the end result but the process of coming to terms with the words in all their polyphonic glory. On the other, our revisions of texts speak, to some degree, about a struggle with language itself. We share an increasing suspicion of the written word – its ability to produce knowledge is perhaps matched only by a certain inability to convey meaning – and of prose with Sufis and poets, respectively.

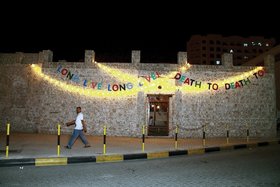

FT: The linguistic structure of text pieces such as Long Live Long Live!, Death to Death to! (2011), or Keep Your Majorities Close, But Your Minorities Closer (2008) is quite contradictory: first you instruct the readers, then you reiterate this instruction by variation, and finally you rebut the entire complex you have just built up. Is this sort of being in-between worlds emblematic for your working methods, too?

S&T: It is not so much being in-between as occupying the far ends of the spectrum, and subsequently perhaps, everything along the way. It is important to push at the walls of interpretation, of activity, and of agency, which otherwise would slowly cave in due to the very nature of growing old, understanding what one likes and dislikes. It's almost like an atavistic counterpart to the neo-liberal idea of aspiration: the longer one lives, the more one understands what one likes, what kinds of ideas, which food, people, places. It's important to resist this 'raffinement', this narrowing of one's field of activity, and to embrace one's antithesis, to read things we don't agree with, to become friends with people to whom we might not normally be drawn.

FT: Maintaining such a contradictory position must be demanding, isn't it?

S&T: It is extremely demanding. A whole range of thinkers have addressed the difficulty of maintaining an intellectual and numinous agility: once you take a position, no matter how liberating, you immediately become trapped by it. Or, as Thomas Merton wrote so eloquently, 'Quit this world, quit the next, and quit quitting'.

Slavs and Tatars is a faction of polemics and intimacies devoted to an area east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China, known as Eurasia. The collective's work spans several media, disciplines, and a broad spectrum of cultural registers (high and low). Slavs and Tatars have published Kidnapping Mountains (Book Works, 2009), Love Me, Love Me Not: Changed Names (onestar press, 2010), and Molla Nasreddin: the magazine that would've, could've, should've (JRP-Ringier, 2011). Their work has been exhibited at Salt, Istanbul, Tate Modern, the 10th Sharjah, the 8th Mercosul and the 3rd Thessaloniki Biennials.

Slavs and Tatars are also participants in the Kamel Lazaar Foundation Projects – view their latest project Mirrors For Princes, here.