Interviews

A Conversation

Ahmet Öğüt in conversation with Basak Senova

The work of Ahmet Öğüt is characterised by a playfulness that questions the reasons behind, and consequences of, socio-political and economic imbalances that have become the realities of our daily life. The artist, who was born in Diyarbakir, Turkey, and who currently resides in Amsterdam, is something of an art-world free-wheeler, un-tethered to a gallery but whose works are visible in cities and collections across the globe.

In this interview with curator, designer and editor, Basak Senova, Öğüt discusses his works, ruminates on the importance of public space and the developing culture of contemporary art presentation in his native Turkey.

Basak Senova: As an artist who started his art venture in Turkey, I would like to start our conversation by asking about the impact of the local sources, movements and actors on your work.

Ahmet Öğüt: I studied at Hüsnü Dokak and Ferhat Özgür's atelier at Hacettepe University's Fine Art Faculty in Ankara. Both of their agendas were interdisciplinary, opposing the entirely traditional structure of the Fine Art Faculty. I remember walking from our campus to Bilkent University's campus, and entering through a back door to get into the big library. That library was the only place in town where I could find a wide selection of international art magazines. Although I didn't know English at that time, I was keen to go through all the images in the magazines for hours, and take note of the dates and artists' names that I liked. Since I wasn't reading but looking at those magazines, going through those images was just like going to an actual exhibition. We should remember that there weren't really any contemporary art institutions in Ankara at the time. There was only one infrequent exhibition (Genç Sanat; in English, 'Young Art') dedicated to young contemporary artists. I was also following art-ist Contemporary Art Magazine, one of the first magazines dedicated to contemporary art from Turkey, which had a big influence on me.

BS: Right after your graduation from Hacettepe University, you moved to Istanbul. How did the experience in Istanbul help to shape to your work?

AÖ: Yes, I moved to Istanbul to get my MA at Yildiz Technical University, Art and Design Faculty. We had very good advisors and lecturers at that time such as Inci Eviner, Güven Incirlioğlu, Necmi Zeka, Bülent Tanju and Uğur Tanyeli, among others. Also very influential was the archive of the Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center. Finally, I had access to documentation of the work of many artists. I spent hours watching all the video works on VHS and VSD by international and local artists.

BS: Apart from a few publications and the SALT archive, there has never been a culture of documenting the development of contemporary art in Turkey. How do you keep a record of your productions and actions?

AÖ: Most people are unaware of the importance of archiving. Once I am done with a work of art, I don't want it to die. It actually starts living from that moment on. It must stay connected with the public. It must be accessible. I document my own work. Most of my productions and actions are reproducible, so it is easy to keep track of them. The hard thing is to take care of the large physical works. I try to keep them in circulation as long as possible. These kinds of works travel from one exhibition to another until I find a permanent solution.

BS: You are not connected to a gallery; nevertheless you have works in reputable collections. You are entirely self-sufficient in representing yourself and your work on an international level. Given that, I would like to hear your opinion about the recent developments in Turkey regarding the capital flow towards contemporary art and the gallery boom there.

AÖ: There are two different types of artists; what I call 'market artists', showing mostly in galleries, and the artists who mainly show in museums and biennials. I also know artists capable of balancing the two, showing large-scale installations in museums and biennials and producing smaller, side-works for their galleries. I prefer not to give up my principles and my primary motivation isn't the saleability of the work. I believe in ideas. Forms and objects are just tools to express and share ideas. Very few galleries can think like this and still be successful in the market.

BS: So, how do you read and follow the current changes that are rapidly shaping contemporary art production in Turkey, alongside the new institutional initiatives?

AÖ: I find the developments regarding contemporary art in Turkey promising, but also dangerous. Contemporary art doesn't have a long history in Turkey, things are only just starting to happen and take shape. We really need to educate ourselves before jumping into this pool. Although many galleries are opening, very few not-for-profit institutions are emerging. On the other hand, big-scale private institutions need to give full freedom to their curators and directors regarding decision-making.

BS: I still see individual efforts (especially those of curators) to be more influential than institutional ones. Given that there is still a lack of intellectual infrastructure on the organizational basis, most of the local institutions are contingently guided and shaped by individuals. Therefore, their assets and even life-spans are always dependent on individuals, not on their institutional reputation or line. In view of that, what are the significant differences between the European institutions and the new-comer local ones?

AÖ: What I observe in Turkey is that instead of taking care of immediate recent history, there is an urgent demand to commission new works so that the institutions can caption their names and be able to say that it was specifically done for them. Opening new institutions with only new works is not enough; we need to claim a historical position.

BS: You have been based in Amsterdam for the last four years. During this time, have you found that the city has shaped your work in new ways?

AÖ: My work always has a lot to do with my surroundings and daily life. Since I moved to Amsterdam, my understanding of public space has changed dramatically, and that of course has affected my practice. I think public space in Western Europe is very much democratized; it doesn't present uncanny situations in the way it does in Turkey. Therefore, in Western Europe, even the sharpest political actions are trapped in the image of a carnival. Of course, there are exceptional situations, like the riots in London in the summer.

BS: What was your first artistic reaction towards this democratized public realm?

AÖ: The very fist work I made after moving to Amsterdam in 2007 was Three Spots. In recent years there has been an advertisement campaign in Amsterdam, a kind of branding for the city, which has the slogan 'I Amsterdam' displayed in public spaces. I was stimulated by this slogan, which is presented in sculptural form between the Rijksmuseum and the Van Gogh Museum. I see how local people and tourists establish a strange relationship with these forms. They take photos of themselves in front of or next to the letters, climb on them, and most important of all, they touch them. I filmed this and edited the letters on the video so that I could create several other words: damned, dream, and desert. Still, you can see that people interact with those words.

I was basically trying to point at another meaning existing in public space, one that goes beyond its symbolic meaning, already sacrificed for cultural tourism by conveying illustrative urban messages.

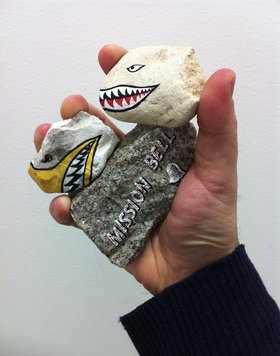

BS: In the same vein, you recently developed the project Stones to Throw (2011) for Kunsthalle Lissabon in Lisbon, Portugal, which has been extended to public spaces in different countries. The project has various phases and states that establish multiple types of relationships with the audience. Could you please explain these phases and states in the course of the project?

AÖ: Stones to Throw started out as an installation. My point of departure was 'nose art', the decorative paintings you see on the fuselage of military aircrafts, which can be seen as a form of aircraft graffiti. On ten stones, I replicated the types of graffiti seen on such airplanes and the stones were then mounted on ten plinths. During the show at Kunsthalle Lissabon, nine of the stones were sent one by one to Diyarbakir, my hometown, and left in the street. What remained at the end of the show were ten plinths, only one stone, and photos of the other stones left in the streets of Diyarbakir and the FedEx bills for their transport. At Kunsthalle Lissabon, it was a process; visitors witnessed stones disappearing from the exhibition one by one.

Now this installation becomes the documentation of that process, with nine empty plinths, only one plinth with a stone and the photos of the other stones located in the streets of Diyarbakir installed on the wall. I decided not to send the last stone, so it actually became the physical documentation of the other stones that had disappeared. I also like the fact that nine empty plinths can still show visitors that there had once been stones on the plinths.

BS: Humour is one of the distinctive characteristics of your work. In this respect, you always use public space as the setting for a humorous act that also inhabits critical stances. For instance, the long-run project Waiting for a Bus (2011) reveals a set of questionings through humour.

AÖ: Waiting for a Bus is a new work I made for the 6th SCAPE Biennial in Christchurch, New Zealand, which was postponed due to the extraordinary circumstances caused by two big earthquakes earlier this year. It has finally been installed. The piece is an interactive carousel that is a playful alternative to a bus shelter, located in Christchurch. The gently rotating carousel has two bus stops on it and people are able to get on, sit and wait for a bus.

It combines the boredom associated with a passive act of everyday life with a playful source of childhood entertainment. Working with the readymade form of a bus shelter, the work is located along a popular bus route.

BS: Speaking of humour and subtlety, how do you find your contribution to the 12th Istanbul Biennial?

AÖ: I participated in the 12th Istanbul Biennial with a piece called Perfect Lovers (2008), by referring to Felix Gonzalez-Torres's 1991 installation Untitled (Perfect Lovers). As you may know, the title, the visual identity, and the themes of the 12th Istanbul Biennial reference the works of Felix Gonzalez-Torres. It has been a nice conjunction that my work happens to fit this theme. In the original work, Gonzalez-Torres placed two synchronized industrial clocks side by side on a wall. In my version, I place a one YTL (Turkish Lira) coin and a two Euro coin side by side. The coins are aesthetically alike but one YTL is worth approximately four times less than the two Euro coin.

BS: What do you think about this last edition of the biennial?

AÖ: I like the fact that the organizers removed the word 'international' from the title of the Istanbul Biennial. I also think there are many good art works and artists in the biennial. However, I must admit that I don't like the fact that they didn't announce the artist list but rather announced their own names before the opening. I would see it as a historical act, if only if they hadn't announced the curators' names either. As for the exhibition design, although it is functional in many ways, I can't escape the impression that I am walking through a sophisticated art fair setting. Also, Istanbul is not the right city in which to ignore public space. For a biennial referencing Gonzalez-Torres, I would actually expect much more multiples of artworks that could have been taken away, so by the end of the biennial half of them would have disappeared.