News

Chapter 31 at P21 Gallery, London

An Odd Piece of Research on the Many Virtues of Oriental Imagination

In Palestine, the answer to the question 'what's new?' is often 'La Jadid Tahta a'Shams', which literally translates to: 'nothing new under the sun'. This common expression has come to echo the state of suspension that has restrained Palestinians throughout their ongoing Nakba: a condition where the present is trapped in a tension between a lost past and an anticipated future. This condition formed the conceptual frame for the group exhibition Chapter 31: An Odd Piece of Research on the Many Virtues of Oriental Imagination, which was curated by Sarha collective, an interdisciplinary platform – created by Nadia Jaglom, a visual anthropologist, and Mai Kanaaneh, with a background in philosophy – that fosters new representations of Palestine and the Middle East through cultural projects. The show featured works by fifteen artists, including Amjad Ghannam, Basma Alsharif, and METASITU Collective, comprising of Liva Dudareva and Eduardo Cassina, and Noor Abuarafeh; the majority of whom produced new commissions spanning a variety of media including video, audio, photography, sculpture, installations and paintings. (Parallel workshops, screenings and performances also took place.)

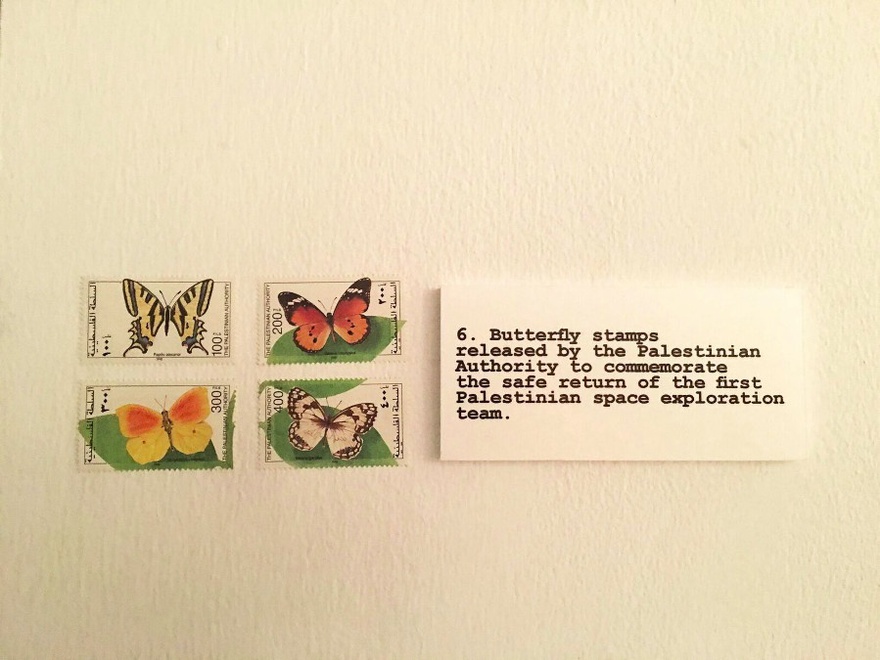

Chapter 31 took its inspiration from the classic satirical novel of Palestinian writer Emile Habibi, The Secret Life of Saeed: The Pessoptomist (1974), which tells the story of a protagonist who journeys to outer-space (a metaphor for the alienation and estrangement that Palestinian's are caught between). Drawing on this narrative, Chapter 31 presented a journey through time and imagination, offering a surreal, if not satirical view of the future by using the frame of science-fiction to provoke concepts of memory, return, repetition surveillance, boredom and stagnation. Visual cues pointed towards an intended time-shift, with the curators fixing extra CCTV cameras around the gallery space, which in turn was peppered with fabricated artefacts, from stamps and souvenir sculptures to excavated stones, all referred to as relics from a hypothetical 'past' located in an equally hypothetical future. For instance, the caption for a set of four butterfly stamps indicated that the insects were 'released by the Palestinian Authority to commemorate the safe return of the first Palestinian space exploration team', offering a bitter sarcasm on the obvious futilities surrounding the potentialities of a future within the Palestinian context.

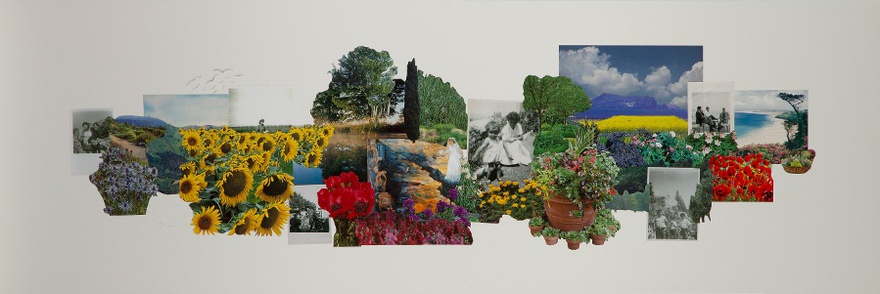

Set on two floors, visually connected by opposite stairways and transparent glass walls, the exhibition was divided into two thematic frames that nonetheless overlapped: 'utopia' and 'dystopia', with the former presented on the ground floor, and the latter presented in the basement. The utopian floor featured works by eight artists, including Léopold Lambert, Shada Safadi, and Wafa Hourani, with most artworks recollecting aspects of different pasts using archaeology, archives, and personal narratives to envisage the future. Samah Hijawi's Paradise Series (2016), for instance, presented four collages, each compiled from personal photographs, images of classical Palestinian paintings, and magazine cut outs of exotic landscapes. These images combined personal and collective visual memories to produce a deceitful allure associated with a touristic consumerist appeal that, on closer inspection, revealed a multi-layered and distorted compilation of incoherent images that offered a fictional fantasy of a 'paradise' that is in fact nothing more than a groundless future predicated on an unstable history. An accompanying audio-track accentuates this harsh reality – an account of the defeated revolution through the experience of a martyred freedom fighter, Laila.

That Hijawi's work was located in the 'utopian' part of this exhibition, pointed to the fact that, while the classification of 'utopia' and 'dystopia' served as an organizing structure for this exhibition as a whole, the Palestinian context made it rather challenging to establish a clear division between the two conditions. This was underscored in Abdelrahman Katanani's Girl with Parachute (2016), a corrugated metal relief sculpture depicting a young girl flying down with a parachute, ironically set on the staircase wall descending towards the dystopian floor, where the girl was depicted again with a hula hoop whose rings were constructed from barbed wires, in the lithograph, Girl with Hula Hoop. As a third generation refugee, Katanani's work tackled the conditions that followed the 1948 Nakba and persisted onwards, including the absence of hope and freedom – a reminder of the persistent tragedy of displacement, and the dream of return that lingers in Palestinian collective memory.

Continuing the overlapping between the 'utopian' and 'dystopian' framings was the work of Alaa Abu Asaad, who was also represented on both floors. Evening Ennui With Mum on a Rainy Sunday (2016), a large-scale coloured photograph presented on the utopian floor, shows the artist lying on his mother's lap, his head covered by an old Itihad newspaper. In the basement, Abu Assad displayed eight black and white photographs including an anonymous male nude trying to cover himself, while on the wall behind him hangs a picture of the last supper; a blurred image of a man being assaulted by the military; and a car on a desolate slope. Within the framework of the show, the photographs projected a staggering sense of emptiness, suffocation and vulnerability inscribed into the states of securitization and militarization, while juxtaposing references of eroticism and sanctity within public and private domains.

Another seven artists were included on the dystopian floor, including Anas al Barbawari and Rafat Asad, all of whom addressed notions of landscape, surveillance, political detention, boredom and the growing power of neo-liberal capitalism. In Yazan Khalili's Hiding our Faces like the Dancing Wind (2016), a video features a woman's face – claustrophobically trapped by a camera screen – repeatedly trying to confuse facial recognition technology, while a sequence of ethnographic masks interrupts the frame. Probing the advancing technologies of surveillance and archiving, and the rising global concerns over securitization and mobility, the video speaks of technology's tendency to typecast individuals, thus recalling colonial mechanisms of racial classifications and the construction of historical narratives through such acts.

Hiding our Faces like the Dancing Wind also exemplified how the themes in the dystopian floor responded not only to political failures, escalated aggression and incessant deterioration experienced in Palestine itself, but to concerns that are far more global. Ayham Jabr's series of untitled prints (2016), for instance, comprised of 12 collages depicting sci-fi fictional terrains, which the artist was obliged to digitize when shipping them out from Syria (the ongoing war in Syria has paralyzed the courier service and has highly restricted mobility in and out of country). The collages offered a sequence of events read as the movement from genesis to apocalypse: the first print included in the grouping depicts the earth in a moment of birth being tenderly held out of water in human hands, while other prints depict Arab characters in Middle Eastern landscapes. The fourth print included in this series presents an interesting simulation of Michelangelo's Creation of Adam, with a metallic upper hand. Satirising divine interventions, the print marks the onset of disaster represented in the images that followed, all of which showed the turmoil of war, displacement and destruction juxtaposed against the perpetuators of such violence, who are shown sitting behind surveillance screens remotely controlling military action.

As a whole, Chapter 31 was a condensed journey across temporalities, geographies and anxieties. Throughout the exhibition, the past, present and future were constantly interchangeable, thus posing a sense of uncertainty and affirming a lingering condition of suspense. Stagnation is what defines the present and informs of the paradoxical tension between the past and the future - utopia could not be fully visualized, just as dystopia was envisaged not only through images of heightened walls and military aggression, but also through personal experiences of control and oppression. The result was an overwhelming sense of suffocation produced from a dense collection of expressions that each conjured a claustrophobic and asphyxiating vision of a future that is already here.