Projects

Engineering Shelter

Introducing the Morrison shelter

'It was impractical to produce a design for mass production that could withstand a direct hit, and so it was a matter of selecting a suitable design target that would save lives in many cases of blast damage to bombed houses. The Morrison shelter was designed to enable…the family to sleep under the shelter at night or during raids, and to use it as a dining table in the daytime, making it a practical item in the house.'[1]

The Morrison shelter was designed by Professor Sir John Baker and named after Herbert Morrison the Minister of Home Security in the UK at the time. The indoor cage-like structure was recommended as a shelter during aerial bombing in 1940. Otherwise known as the indoor table shelter, it was provided free to households whose combined income was less than £400 per year.

The indoor table shelter was distributed as an assembly kit with instructions on where to place it, and how to build the 6 foot, 6 inch long by 4 foot wide structure. Consisting of approximately 359 pieces including a 3 millimetre steel top sheet and wire mesh sides, it was constructed using three tools that were supplied as part of the distributed pack.

Over half a million of the self-assembly shelters were sent to homes across the UK by 1943, designed that it was not intended to be secure enough to withstand a direct hit from aerial bombardment, but rather to act as a suitable shelter in some cases of blast damage.

Before, after, and the Missing Snapshot

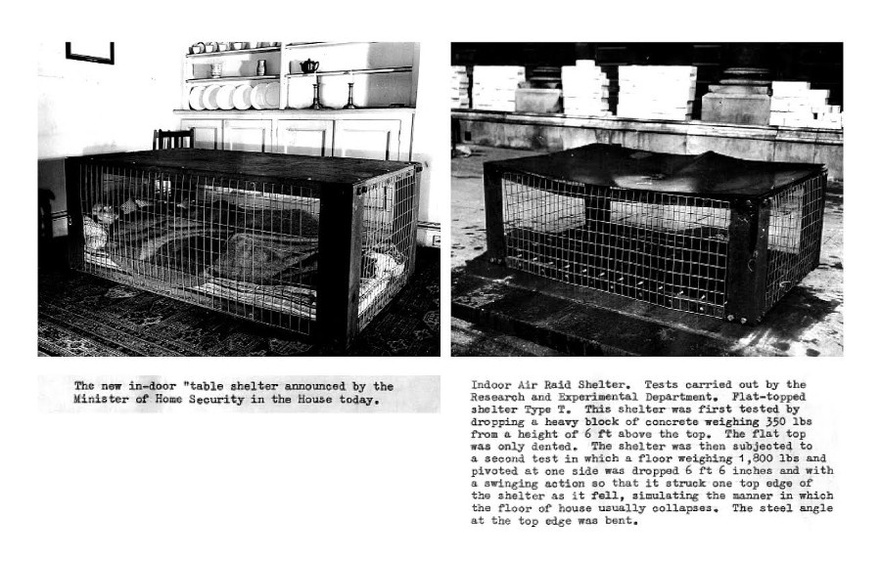

The two images shown here were included in the public announcement recommending the use of the indoor table shelter. The first image shows a civilian couple, apparently sleeping comfortably inside, whilst the second image presents the table shelter after having been subjected to an experiment aimed to simulate a similar level of violent force as anticipated during aerial bombing. The image states:

Indoor Air Raid Shelter. Tests carried out by the Research and Experimental Department. Flat-topped shelter Type T. This shelter was first tested by dropping a heavy block of concrete weighing 350 lbs from a height of 6-foot above the top. The flat top was only dented. The shelter was then subjected to a second test in which a floor weighing 1,800 lbs and pivoted at one side was dropped 6 foot 6 inches and with a swinging action so that it struck one top edge of the shelter as it fell, simulating the manner in which the floor of the house usually collapses. The steel angle at the top edge was bent.

When first viewing the archive images, I was struck by the illustrative dynamic that they perform. As 'before and after' images, they form a visual relationship which constructs a narrative testifying to the effectiveness of the shelter, using the conducted scientific experiment as a way of confirming the safety that this material apparatus provides. However, the image also creates a vivid description for the public imagination, of the extremity of the violence that could take place during a possible attack. Through the experiments, the government attempts to validate the newly recommended shelter by quantifying and accurately simulating the irruption of potential violence within the domestic space. Yet through and between the 'before and after' images, an imaginary third image is generated – a missing snapshot, as it were, of an experience of the worst. These images are therefore employed in a mode of visual communication that goes beyond the stated facts but seemingly in two contradictory directions: attempting to calculate and manage the potential risks faced by those it advises to use this type of shelter, and simultaneously encouraging an increased sense of danger, therefore both constructing and deconstructing the home as a site of security.

Whether the intended effect is to enhance fear or to reassure, the simultaneous projection of an image of security and insecurity into the public imagination coincides with a particular extension of governance into the materiality of the domestic environment. The government promotion of the indoor table shelter raises questions not only about the truth status of the public information, but of its real intended function.

The Home Under Threat

The domestic space – the home or the house – is the site where a complex range of values converge; a set of values rooted in the necessary function that the architecture of the home provides a practical solution to the human need for shelter from adverse conditions. Shelter is provided by the architecture of the home as it forms a material layer and the assessment of the potential strengths of that material suggest that it should be stronger, more durable, and more able to withstand the adverse conditions or exterior threat that the human needs protection from. By this process, the shelter that the home provides is an essential human right.

Under a condition of heightened insecurity, produced through armed conflict or natural disaster, the architecture of the home undergoes a radical shift. As an occupant, the understanding of its materiality changes as it becomes the site where a series of small-scale actions are undertaken in anticipation of an exterior threat, as witnessed, for example, with the indoor table shelter. These small-scale actions are a precarious attempt to fortify the home against violent exterior forces. The actions in anticipation of risk, together design an environment in which the fear of the future is continually being rehearsed, forming a relationship between time and space: as in the future yet to come, and the space in which that future may yet occur. The psychological fear of living with this potentiality alters the material components that constitute the home by providing a constant reminder of the potential risks that lie-in-wait. Within this condition, what are the natural and political forces that shape the home as an adequate shelter?

Plasticity over Elasticity

As scientific adviser to the Design and Development Section of the Ministry of Home Security, Professor Sir John Baker designed the Morrison shelter using his newly developed plastic theory of structural analysis.

Metals are understood to behave in two ways, elastically or plastically. Elastic theory is when an elastic deformation takes place. This is when the deformation of metal through applied force or pressure is reversible, meaning the material will go back into its original shape. Plastic theory observes the material after the 'yield point', where the molecular structure of the metal is permanently altered, meaning that the force or pressure applied to the metal is great enough that the deformation is non-reversible.

The two theories explain the point at which steel will fail. The benefits of applying plastic over elastic theory, is that it gives a wider threshold of use, however there is less margin of safety leading up to a catastrophic failure point.

The first papers on the progress of the plastic theory were published in 1936.[2] Professor Sir John Baker's newly developed plastic theory enabled a greater application of the use of steel in his design of the shelter, however when the Morrison shelter was mass-produced and distributed in 1940 to over half a million mostly low-income households, the design theory that its safety was based on was entirely new and untested.[3]

The Missing Snapshot

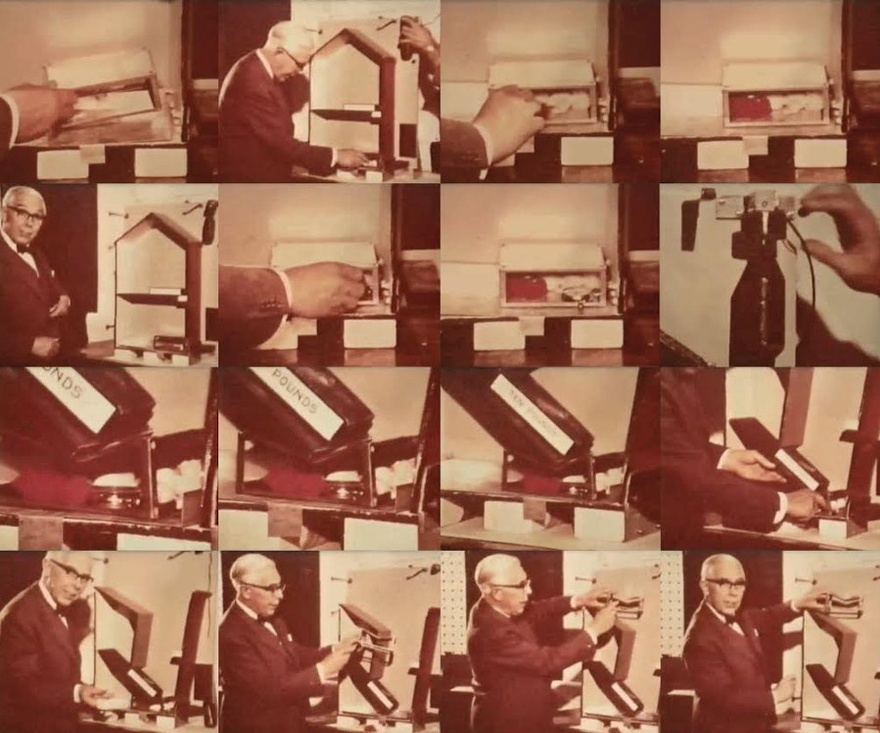

The re-enacted experiment and the featured table shelter were modelled using the information from the archive images, a method adopted to reveal their manipulative power, in that the domestic scene is so perfectly portrayed: the comfortably sleeping couple, the decorative plates standing upright on the shelves behind the shelter illustrating a scene of peace and tranquility.

At least half a million households, most of which were low income, were subjected to a higher threshold of risk through the engineering of the Morrison shelter. In the case of an indirect strike, the shelters were designed to squash down plastically by up to 12 inches. Published statistics on the Morrison shelter, which observed 44 damaged houses, found that three people had been killed, 13 seriously injured, and 16 slightly injured out of a total of 136 people who had occupied the shelters. It goes onto say that the fatalities that did occur were as a result of the shelters being placed incorrectly in the homes.[4]

This is an example of how emergency shelter more often is formed through a set of political and economic conditions that don't always reflect what is actually necessary for protection. Performing the task of building the table shelter and re-enacting the experiment made tangible the risks people faced by putting the safety of their bodies, and the fragile bodies of the ones they loved, in the precarious position of using the shelters, perhaps knowing that they had no other choice.

Following the end of World War II, the government, apparently for reuse of the materials, recalled all the Morrison shelters.[5]

Information of re-enacted experiment:

Date: Tuesday 8 September

Time: 3.55pm

This work was commissioned as part of Space Interrupted (2015) an exhibition that took place at Fort Brockhurst in Portsmouth, in connection with English Heritage and the British Arts Council. The exhibition asked the participating artists to disrupt, engage, and reframe the industrial architecture of the unique site. The performed re-enactment of the experiment conducted on the Morrison shelter shown in the 'before and after' images from 1940, was initiated as an enquiry into the truth claim of the archival material itself.

Read Helene Kazan in conversation with Amal Khalaf here.

[1] From a lecture by Professor Sir John Baker on the principles of the design of the Morrison shelter at Cambridge University, 1946.

[2] The papers were published as part of a congressional meeting in Paris by the international association for Bridge and Structural Engineering (IABSE). Jacques Heyman, Structural analysis: a historical approach (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 127-153.

[3] It was not until 1943 that the theory was implemented for the first time in the design of the Cambridge University Engineering Department, of which Baker was appointed Professor of Mechanical Sciences.

[4] 'Examination of effectiveness of Morrison shelter', Learning Curve website, http://www.learningcurve.gov.uk/homefront/bombing/shelters/source2.htm.

[5] Witness statement taken on 13 September 2015, Fort Brockhurst, Portsmouth.