Projects

A Dictionary of the Revolution

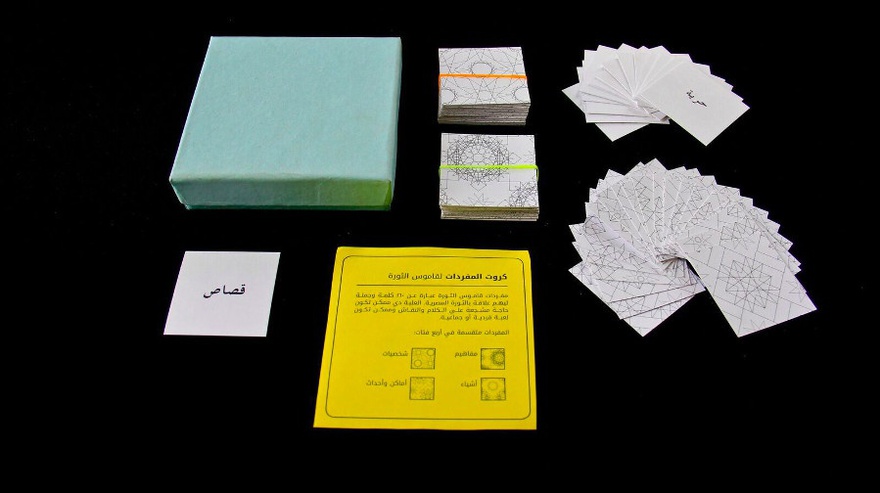

A Dictionary of the Revolution is a project that documents the rapid amplification of public political speech following the uprising of 25 January 2011 in Egypt. To engage a large and diverse group of people in the documentation, I created a vocabulary box containing 160 words in Egyptian colloquial that were frequently used from 2011 to 2013 in public political conversation.

The words are in four categories: concepts, characters, objects, and places & events.

In 2014, the box was used in around 200 conversations with individuals across six governorates of Egypt: Alexandria, Aswan, Cairo, Mansoura, Sinai and Suez. Choosing cards from the box, people talked about what the words meant to them, who they heard using them, and how their meanings had changed since the uprising. Using transcription of this speech, I'm weaving imagined 'national dialogues' around each of the terms in the lexicon.

These texts are translated from the original Arabic.

YOUTH (shabab)

Our greatest strength is our youth.

The informed youth are stronger than the Muslim Brothers, stronger than the Islamists, stronger than the police and stronger than the Army. They were stronger than anyone. They were stronger than the President, and stronger than the state. It's great that they have clear minds, and they are the country's hope.

Before the revolution, the youth were oppressed. They couldn't get married, couldn't get work, couldn't get housing. They couldn't get anything, and they were frustrated. So when the revolution happened, they said,

'The country is going to be fixed, and we'll get work, and whoever's not already married will get married. Everything's going to be fixed and it'll be better than before the revolution.'

The youth who rose up, rose up from all the pressure and the frustration inside them. They rose up to express their freedom, to say that we are the youth of Egypt and no ruler can rule us, because we really are Pharaohs and no one can stop us.

Without a doubt, the youth were the fuel of the 25 January revolution, and they are the vanguard of the future.

As I see it, this revolution was a revolution of youth. They are the ones who went out and moved the stagnant waters of the last 30 years.

After the revolution…after the revolution succeeded and Mubarak left, nothing happened. They returned to the way they were, and their frustration increased.

Unfortunately, the youth didn't get any rights after that change.

We tried. In the end, they cursed us in the media and that was it. We're the ones who destroyed the country, we're the ones who made it this way.

At one point the media held up some of the youth, then after a while it brought them back down again. That's it. I mean how can you tell me that the youth are the backbone of any state, that the state is propped up by the youth and that's a good thing and stuff…all that talk and then you insult me, you arrest me, and you kill me as a young man.

We took far too many steps, following the youth at every stage, and the results weren't positive. It's a youth revolution but it isn't organized. If it were more organized, if they had organized themselves around one thing, there would have been more results. The children of Egypt came from all different leanings; they didn't reach a coherent understanding.

We exchange accusations with our kids. They say that we ruined the revolution, and we say to them that you didn't rise up to the occasion as you should have. They thought that we shouldn't have gone out on 30 June and say to the Army,

'Be with us so we can get rid of the Muslim Brothers.'

There was no guarantee with the Muslim Brothers and we couldn't stop them because we are peaceful and they are not. That's clear now anyway; that a lot of people would have died. I say to my kids,

'There were things you needed to do that you didn't do.'

So what's your part in it?!

The youth who don't go to vote and don't want to state their opinion - who didn't go, who stayed silent, who left the elders to it and then sat around accusing them:

Do your part!

When you do your part, go out and state your opinion, and then nothing happens, then you can talk.

In a little bit of time, I'd say maybe 10 years, if there's a climate with a bit less corruption, and the youth can get work, we'll see Egypt in a very good place. Follow that with another twenty years, and we'll get to the same place that European countries are in. But unfortunately the youth need to be enabled, and corruption has to be set aside a little bit.

Now you say to yourself,

'I haven't got any more hope that the revolution will achieves its goals, except when the useless generation is ripped to shreds and the new generation comes.'

I don't think that youth is about age. It's about people with free, enlightened minds. You can find someone who is forty years old but who goes to Tahrir Square, so the word youth doesn't necessarily mean young.

As long as you're living life, you're still learning. As long as you're learning, you still have spirit, and you have to use it. As long as you're still thinking, you should fight for your ideas, stand beside them. If you're convinced by something, you'll make it happen, no matter what your age.

I see older people going out in marches and demonstrations. There are a lot of them there. My mother still goes. I respect her for that, because she goes to fight for what she believes in.

FUTURE (mostaqbal)

Before the revolution, the future was dark and everything was broken, but the country was going well.

Before 25 January, there was no future at all. The future was black. Everything went by bribes and connections. The son of a minister, a minister; the son of a doorman, a doorman.

During the January revolution, there was a dream for a better, brighter future.

After 25 January and the resignation, you felt like there was a better and brighter future.

The future got hazy. Meaning, you couldn't see that there was a future.

In my opinion, it's unclear. And there's still no hope that our future will become clear.

Everyone wants to see that tomorrow will be a good day, and that the future will be great with the presidency of General El-Sisi. But I'm doubtful of the whole thing, to be honest. But we have hope for him, I swear, we have hope.

The problem is that we have a problem, but people don't see that we have a problem. Nothing has changed. The economy is collapsing, and people don't think there's a problem.

Anyone running for office always sits around talking about the future and how it will be beautiful and I don't know what else.

I won't listen to any who says, 'Tomorrow is coming and tomorrow is beautiful'.

No, tomorrow is not coming and it is not beautiful. It's not coming, it's not beautiful, and we are all distorted.

How can you say tomorrow and there's no social justice?

How can you say tomorrow and there's no security?

How can you say tomorrow and there are no human rights?

How can you say tomorrow and the police are thugs?

How can you tell me:

'Tomorrow'

There is no tomorrow.

Tomorrow will be black days. Black days!

The whole world's future, because of the economy, is going straight to hell. The future of the Middle East has gone completely to hell because of the ongoing revolutions. So what about Egypt, which is affected by both of those factors, not to mention the foreign markets? Its future is completely hazy and dark.

I feel like the future is totally frightening, and it will be so much harder than now.

I feel like the future will be more crowded.

I'm starting to get scared about my future. As I keep getting older…yeah, I know I'm only 18…but still every day I get more scared for my future. I feel like my country isn't going to offer me what I want. You know that up till now we're still renting our apartment? We don't even own an apartment! All of that since our country doesn't offer housing for its citizens. I'm scared, I'm scared to get older and get married, and still not have an apartment.

We have a problem in Egypt. All the people are in different classes. You'll find people waking up in the morning and the day goes like this: wake up, sit by the pool, go home. Everything's just perfect, that's the whole day, and they stay up all night with their friends. Now let's look at another person who gets up dejected in the morning, works so hard that he can barely see in front of him, and what he takes home barely covers anything. What he takes home in a month he spends in two weeks.

There are three things that can work out in this country: military officer, judge, or police officer. Those three are the ones who really live in this country. What does a normal citizen want? Housing, a living, and freedom to walk around with no one bothering him, not an officer or anyone, as long as he's following the law. The law that's in the interest of the citizen, not the law that's in the interest of those who rule them.

The electricity goes out now. If I protest, they'll take my future for 15 years. That's the future: a black future.

So you're talking about a state that is going to do what for you? Basically the state doesn't even exist. You find things in it that aren't right; things aren't in their right place. To put things in their right place takes a lot of effort. To really look to the future, Egypt has another 10 years in front of it.

And if any change is going to happen after this, it's going to be from the coming, young generations, not our generation. The younger generation that's in secondary school now. The younger generation that…maybe it's a double-edged sword…but they don't respect anyone. They literally don't care about anyone. That's a good thing. The truth is that they will take their rights and that's what's needed. That's what they do.

I saw them going out in marches, they were going out in demonstrations and they were not afraid. They stand there not afraid of anything at all. How did they get that feeling? They saw their siblings die. They saw their older siblings lose their future. They don't have a future, they have no education, they don't work. So when they see their siblings like that, what are they going to care about? Really, what do they have to care about? They definitely won't care about anything. So I see that these young generations…I mean I hope to God that they'll make some change. I hope to God that they'll do something.