Projects

The Missing Link 3

A Mother's Tongue, On Ahmad Ghossein's film My Father is Still a Communist

INTRODUCTION

In the third and final installment of Marwa Arsanios’ ‘The Missing Link’ project, in which the artist attempts to get closer to the elusive auteur Christian Ghazzi and the conditions of production surrounding his 1972 film 100 Faces in a Single Day, the spotlight falls on the contemporary Lebanese filmmaker Ahmad Ghossein and his 2011 film My Father is Still a Communist. Commissioned by the Sharjah Art Foundation, it is a portrait of a marriage at a transitional point in Lebanon’s social and political history, brought to life through tape recordings of Ghossein’s mother and father speaking to each other whilst the former was working abroad. Absence, memory and nostalgia permeate the work, which shares a number of similarities with Ghazzi’s film 100 Faces in a Single Day and offers, perhaps, another of reading its central themes.

THE MISSING LINK 3: A MOTHER'S TONGUE, ON AHMAD GHOSSEIN'S FILM MY FATHER IS STILL A COMMUNIST

In the previous texts, ‘The Missing Link’ and ‘The Missing Link Part Two’, I talked to several filmmakers and actors about Christian Ghazzi’s 1972 film, 100 Faces in a Single Day, focusing on the influence this movie had on their own works. In this final section of ‘The Missing Link’, I started talking to Ahmad Ghossein with the intention of discussing Ghazzi’s film, but the conversation very quickly diverged into a discussion of his 2011 film My Father is Still a Communist, mainly because I had recently seen it and was very affected by it. Nevertheless, as this conversation unfolded, I realised that Ahmad’s movie speaks to Ghazzi’s film in a way I had not anticipated. This is not only because of the political content of both films – which are separated by almost 40 years – but on a formal and aesthetic level. The sounds and the images in both confront one other and interrogate the events as they unfold. Although Ahmad’s position is more distanced in relation to the material he is examining, there always seems to be something missing, something awry and in absentia – perhaps this is the ‘full’ picture that Ghazzi wanted to present in 100 Faces in a Single Day: the sense of an absence that is always present, and a presence that seems precarious at best and forever in danger of becoming absent.

When the father is away, and becomes this ghostly authority that the mother invokes when she wants to dominate or re-impose discipline in the chaotic family unit, the child obeys.

Fear and admiration build up towards this imaginary authority, and the father finds himself next to other cartoon heroes in the wild imagination of the child. Superman, Batman, Captain Majed …

He was a fighter, a strong one, closer to the imagery of the fedayeen in Christian Ghazzi’s film 100 Faces in a Single Day.

Tell me more about him?

It was this question, posed by Ahmad Ghossein to his mother, which led him to unlock his parent’s deepest secrets by listening to their intimate conversations. Through 50 hours of tapes recorded over a ten-year period when the father was away working in Saudi Arabia, the filmmaker went in search of his father and mother. Recording her voice on the A side of a cassette tape, Ghossein’s mother would then send the tape to his father and wait for it to come back with his voice on the B side. It was a common way of communicating when cassettes were still in use and telephone lines were down – a sort of recorded letter.

It was time to know who this guy really was. Why was he away?

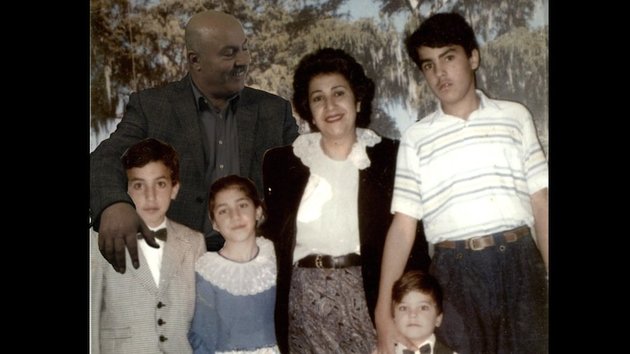

Ahmad went through the tapes with all the emotional provocation that comes about with such an endeavour. Listening to what could be called the archive of his parents’ relationship, he became privy to the numerous discussions between the couple, their arguments, financial worries, the practicalities of their lives, their love and deep intimacy. If the intention at the beginning was to get to know the place of his father in his world, through this process of listening Ahmad radically erased his father’s voice through having only his mother’s A sides audible on the final film – enhancing, on one level, his absence – and the heroic image of the father was replaced in the film by a few shots where we see him as an older man trying to enter their childhood pictures, making a caricature of the hero he once was. It is a classic fall from grace, where the child doesn't exactly kill the father, but plays with him like he would play with his own heroes.

How do you speak?

In one of the scenes we hear Ahmad talking to his father via tape with the hyper-activeness of a child interrupted from his play and rushing to get back to it:

‘Hi Dad. How are you? I hope you are good. I hope you are happy. How is work? I hope you are making money ...’

For a moment, we think that we understand the father’s role in this situation: he is the provider and this gives him an important role in the midst of a less than ideal economic set-up, which translates, as far as Ahmad is concerned, into having to wait for a new pair of boots.

‘Slowly, slowly, talk slowly’, yells the mother in the background. But the tape is 60 minutes long and one needs to talk quickly and precisely before the tape ends; or conversely, really slowly, browsing radio stations and recording whatever songs pop up just to fill the time on the A side. One doesn't always have much to say. But in any case, whether filled with words or music, the tape needs to be in the luggage of a traveller the following morning and on the road in order to reach his father’s ears.

In this mode of communication, language suddenly becomes precise, contained and very structured, seemingly organising the family chaos. When one usually has a conversation in Arabic, things can go over the top, in the sense that synonyms are repeatedly used in a single phrase, and there is a lot of unnecessary jargon. But here Ahmad’s mother was very controlled. Flirting with an almost bureaucratic vocabulary, she seemed to have acquired a precise mode of speaking. We can tell by the way she aligns certain words with others that she was immersed in a specific political organisation at that time. This becomes clearer with the certain terminologies she uses.

‘Believe it or not, my father still uses this language’, says Ahmad. And this is exactly why the title of the film is My Father is Still a Communist. Language and terminologies belonging to a certain epoch and a certain ideology become a trace or a ruin, just as much as the house that is pictured throughout the film is a ruin: a concrete building that was neither completed nor about to be completed.

What’s the time?

The duration of the tape defines the selection of the words that, in turn, defines the selection of the issues to be discussed.

In the same process of overt selection, Ahmad had to reconstruct this story by selecting passages from the 50-hour-long recording. He takes us through his parents’ relationship, the tension building between the couple as the economic situation worsens, and the distance already between them slowly widening as a result.

We, as the audience, suddenly feel involved in the relationship and start taking sides. We find ourselves blaming the father: Where is he? Does he really exist? Why isn’t he answering? Suspicion mounts. We ally with the mother; we love the father when she loves him, and we blame him for not bringing enough money in to finish building the house. If he is not even fulfilling his role as bread-winner, what then is his role? Not a hero, not a fighter, not a provider, just an old man forcing himself into the childhood pictures of his family.

The father left his village as a communist when the party still had a strong base in the south of Lebanon and returned as a communist trying to find a place for himself in a political landscape that had completely changed and become more extreme. But he still believes that he can force himself back into the picture – literally and metaphorically.

‘If you go down south on sundays nowadays, you smell money. Do you know how you smell it? You smell barbecue, everyone is barbecuing, this is an indicator of money. You would never have this before’, Ahmad tells me.

In fact, the political and economical landscape has changed drastically in southern Lebanon since 2000, when the Israelis pulled out, and money from different sources – whether diaspora or political parties – has poured in, and the landscape has been re-shaped by religion, big capital and an industry of sectarian martyrdom. But the voice of Ahmad’s mother, which is overlaid onto recent footage shot in southern Lebanon, questions this landscape. In Ahmad’s film, it is her voice that transforms the landscape; it is her resistance to a certain dominant ideology, her body moving to music and her desire for a far-away husband that has the power to transform this landscape into something other than what we are looking at.

Counting and accounting

She is counting the days to see him, or accounting for the money he needs to provide, or counting the money he needs to bring back before he can come home, or accounting for food and vegetables.

She misses him. We hear her say: ‘One kilo of tomatoes is now 100L.L … We eat meat once a week … I haven’t seen you in three months, I can’t tell you how much I miss you … You cannot come back if you don't have at least 90.000L.L., not 80.000L.L., not even 89.000LL, I am telling you 90.000L.L …. I took the money from X and now we are spending X per month …’

Counting time, counting money, listing food, missing the other’s body, missing the other’s voice, buying shoes, leaving, coming back, counting money, accounting for money, accounting for all the years, accounting for love. How can love be valued or weighed?

‘Life will pass us by and we will become old’, she says.

Sounds and images

The deep melancholy of bodies in love, unable to meet as much as they had wished to, forcibly comes through in this film. A shot of the mother undressing in her room makes one think of time passing, as her words from the past penetrate her body – a body that still desires.

A shot taken from an old tape shows her dancing at her brother’s wedding. Yes, the landscape did change, and the bodies too. And if the sound from the tapes used in the film functions as a clear portrait of those times of war, economic crisis and migration, the image opens the dialogue between these two moments that are dialectically related to each other. The now of the image becomes the 80s and the sound of the 80s enters the landscape of southern Lebanon today.

They transform each other and hate each other as if reproducing the parents’ difficult relationship. But they also ignore and deny each other because they speak in different languages.

The terminologies, the bodies moving to the music, the crisis, the ideologies, the beliefs, the disavowals, the conditions of labour: all are penetrating this new landscape that smells of barbecue, death and money. A dead landscape that fakes its concrete smile. But a beautiful naked body that still remembers its own desires, its own ideals, its own languages.

Is this the missing link we have looked for all this time?

Ahmad Ghossein is a filmmaker. He won the Best Director Prize at the Beirut International Film Festival (2004) for his short film Operation N… after having graduated with a degree in Theatre Arts from the Lebanese University. He has since directed several documentaries and video works including 210m (2007) produced by Ashkal Alwan, Faces Applauding Alone (2008), What Does Not Resemble Me Looks Exactly Like Me with Ghassan Salhab and Mohamad Soueid (2009) and An Arab Comes to Town (2008), a documentary filmed in Denmark produced by DR2. Ahmad is a performer and is one of the founders of Maqamat Dance Theatre.