Projects

On-longing

A Project by Saba Innab

INTRODUCTION

The urban realm no longer carries with it all those aspirations of individuals and the collective experience. Those aspirations have been absorbed in the increased accumulation of capital and the materialisation of dominant spaces of consumption – spaces where the experience of place and places of experience withdraw into commodity signs promising the 'good' life. A question therefore arises: for whom exactly is the city being planned? This is the question posed by artist and architect Saba Innab in her project On-longing (2011), which investigates the urban makeup of Amman through the use of aerial photographs, AutoCAD maps and tracing paper to, in her words, 'highlight certain spaces to create a parallel narrative of the city and construct another 'reality' or situation through collage, re-tracing and diagrammatic accounts of the city'.

ON-LONGING, A PROJECT BY SABA INNAB

The urban realm no longer carries with it all those aspirations of individuals and the collective experience. Those aspirations have been absorbed in the increased accumulation of capital and the materialisation of dominant spaces of consumption – spaces where the experience of place and places of experience withdraw into an image of commodity signs promising the 'good' life. A question therefore arises: for whom exactly is the city being planned?

Cities grow towards patterns of urban living that are stationed around capital accumulation and their capacity for consumption. Those patterns put the city on display as a field of opportunities, by creating a free market liberated from the state. Cities generate a fully commoditised form of social life through large-scale development practices and regeneration projects that reflect procedures enforced from 'above'; targeting highly significant and meaningful places in the city; and promoting a 'theme' that exceeds the intended design and producing images of privatised public landscapes speaking to a customer rather than a user.

Gradually, the city turns into a commoditised experience, an image that triggers an excessive degree of marginalisation, gentrification, and dislocation, and increases the spatial/social segregation in the city.

In a city like Amman, a city that portrays itself as a temporary/permanent reality, such developmental practices enhance the dramatic schism between the 'domestic' and the 'urban'. The temporal factor plays a significant role here in how people 'domesticate' their urban experience, by limiting it to their basic needs of dwelling, and restricting their movement to boundaries of inclusion and exclusion imposed from above.

This relation is further complicated by how Amman was and is growing. This growth has always been subject to events enforced upon it by regional economic and political conditions, which were all reflected in the morphology of the city when it was in its formative years. Urgent needs called for fast, arbitrary solutions that caused confusion in the city's overall structure. This was followed by efforts to redeem the fallout: a reaction, and then a re-reaction. The city was thus shaped by these reciprocal actions, creating a multi-centred, spatial reality that is infinitely shifting.

The issue here is not to criticise such projects and what effects are generated from the twin processes of gentrification and displacement, because they are a natural consequence of capital accumulation everywhere. However, in the case of Amman, a political dimension reveals itself in parallel to these practices, where a layer of 'targeted' gentrification appears as a form of reclamation of places after abandonment, public spaces in particular.

To be able to understand the failure of the 'public' in carrying out the aspirations of a certain milieu, we have to map history onto places and understand the genesis, the shifts, the abandonments and the 'comebacks' in the urban configuration, and those patterns somehow explain or scan the relation between power, the political power or the ruler from one side, and the spaces and their representations and identifications on the other. Mapping history onto space leads us to recognise the centrality of cities, particularly those that are in the process of constructing 'nationhood', as well as other forms of political domination.

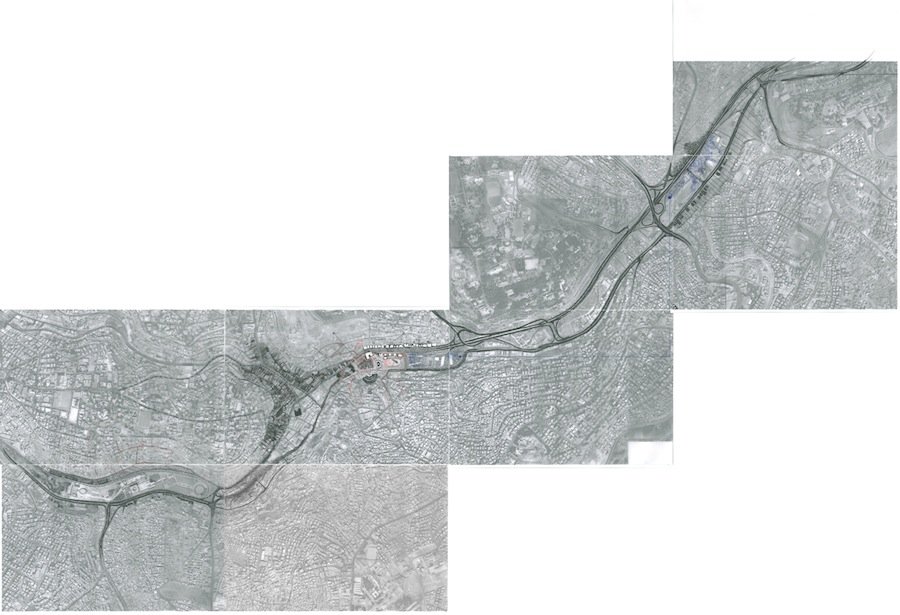

The map becomes a tool for tracing centres in relation to power and the different representations along a time span, making use of aerial photographs, AutoCAD maps and tracing paper to highlight certain spaces to create a parallel narrative of the city and construct another 'reality' or situation through collage, re-tracing and diagrammatic accounts of the city.

This project, On-longing, has involved me working with photographs I took of the city's edge, an area that reveals so much about the city and its centre. These are enlarged images in which I erase all signs of habitation and replace them with mega-structures, Utopian constructions, or even perhaps a dystopian facade. I am working with the contradictions that we have normalised over time; the imagined versus the real, the inflated versus the rural, and the permanent versus the temporary.

IMAGES

The inscriptions of the relationship between the ruling and the public space: the Roman Temple and the Agora, the Royal Palaces and the Hashemite Saha. This diagram is one of the attempts that tries to map this replica, and failure of this plaza as a public space.

A mixed-media map made out of 8 A3 modules tracing the dislocation of public transportation hubs in two locations that are framing the downtown area, and relocating them on the periphery of the city. This is trying to analyse the impact of these shifts, bearing in mind the proposed developments for these particular areas that are being voided of their daily users.

Al Saha al hashemeyeh and Raghadan Bus terminal at the eastern end of downtown, the City Hall building in Ras el Ain at the western end of downtown, and Al Abdali bus terminal at the end of Salt Street linking downtown to west Amman and other places in the city. This triangle defines, or maybe confines, the downtown area, and is a representation of this 'return' or reclamation of these centres by the political power in a way that emphasises the complete denial of the accumulation of certain stories and representations. This return is constructed through three development projects and large-scale urban regeneration projects that focus on the idea of 'heritage' as a frozen material image and avoid dealing with the space as a social product. Those targeted areas are extracted from the map, thus the interruptions in movement, dwelling, and exclusion in the city is further visually highlighted.

The camps and the royal palaces: a map of the eastern edge of downtown Amman showing the location of the first royal palace – Raghadan Palace – built in 1927. Another royal palace was built by 1957 towards the west of downtown, gradually abandoning the old royal/institutional centre. In a city that is constructing itself in the framework of nation building as a whole, every 'ruler' has come with a new palace location, a mosque in the name of the late king, a public space and even a museum! The most recent shift of the seat of power, to the far west of the city (Hummar), is a shift that appears to be turning its back on the whole city. It also defines the class of its nearest dwellers. Close to this new location, a new centre has emerged that revolves around extreme patterns of consumption.

All images by Saba Innab, 2011. Courtesy and © the artist.