Publications

Qalandiya International 2016

O Whale, Don't Swallow Our Moon: Ramallah

O Whale, Don't Swallow Our Moon

Location: Ramallah

Venue: Khalil Sakakini Cultural Centre, 4 Rajaa’ St.

Dates/Times: Open Saturday to Wednesday: 9:00–21:00, Thursday: 9:00–16:00 and closed on Fridays. Runs through 31 October, 2016.

Organizers: Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

Curator: Lara Khaldi

Artists: Jumana Emil Abboud

Click on the links below to visit each section

O Whale, Don't Swallow Our Moon: An Introduction

The Jinn and Their Magic Sleep Now, Like the Water that Hides from the Sun: An e-mail exchange between Lara Khaldi and Jumana Emil Abboud

O Whale, Don't Swallow Our Moon

A Solo Exhibition of Jumana Emil Abboud

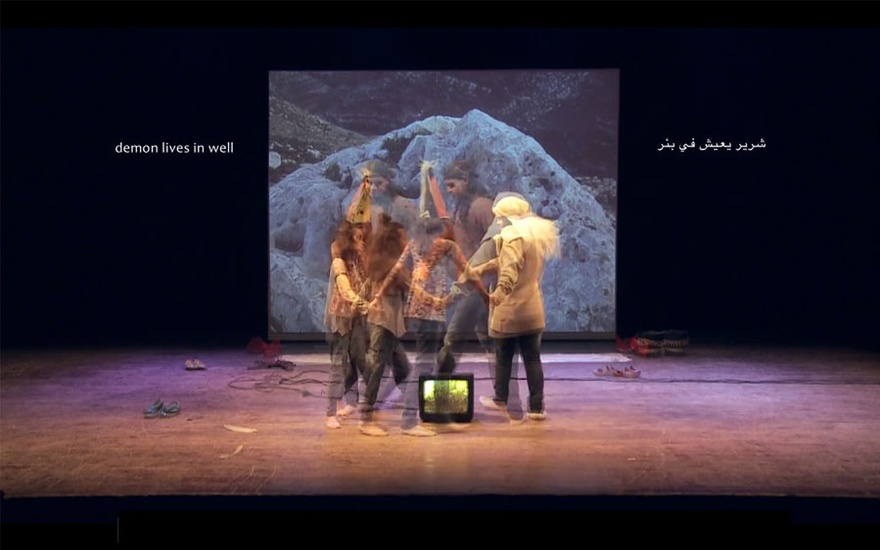

The exhibition O Whale, Don't Swallow Our Moon brings together recent and old work by the artist including drawings, videos, installations and audio recordings. Abboud assembles together and presents for the first time objects, talismans, drawings, and figurines gathered during years of research and voyaging in the actual and fantastical sites of Palestinian folktales and beliefs. As well as the latest version of her ongoing work, Hide Your Water from the Sun, video installation and drawing series, an ongoing research based work made in collaboration with Issa Freij, which departs from an essay written by Palestinian Ethnographer Tawfiq Canaan in the 1920s about haunted water wells and water demons in Palestine. O, Whale Don't Swallow Our Moon is the namesake of this exhibition. The title which is the eponymous video made in 2011 by Abboud, originates from a folktale in the anthology of Palestinian folktales "Speak Bird, Speak Again", whereby a woman falls down a water well, and is said to have been swallowed by a whale, and common folk beliefs where an eclipse is caused by a whale gulping down the moon. The video is a filmed performance scripted by the artist and performed by children. It is a playful take on the folktale, where the children play the different female gender roles prescribed in the folktale (bride, mother, homeland and ghouleh). A large body of drawings produced since 2005 will also be presented, it is a constellation from the artist's oeuvre on Palestinian folktales and beliefs concerned with water. Lastly the installation A Happy Ending: Bodies and Beings from Magical Palestine is an adaptation of an artwork from 2014, reflecting on a tale of a Ghoul that keeps people's eyes and souls trapped in jars.

In the wider context of Qalandiya International and the theme of Return, the exhibition compels one to ask questions about the return of the fokltale. Although they are kept captive in the confiscated haunted sites, how does one return to these sites? What does the return to and of those magical creatures and beliefs mean? Perhaps it is a return of the real or the repressed, whereby that which is forgotten and repressed returns to disrupt and interrupt fixed identities and certainties.

The exhibition is curated by Lara Khaldi and co-commissioned by Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center. With the kind support of The Danish House in Palestine (DHIP) and the Centre for Culture and Development (CKU).

The Jinn and Their Magic Sleep Now, Like the Water that Hides from the Sun

An exchange of e-mails between Lara Khaldi and Jumana Emil Abboud

The following dialogue between Lara Khaldi, curator of the solo exhibition O Whale, Don't Swallow Our Moon, and the artist Jumana Emil Abboud was exchanged in the weeks leading up to the opening of the exhibition. The discussion revolves around the artworks presented in the show as well as Abboud's practice in general. The exhibition brings together a series of new and past works which deal conceptually and aesthetically with Palestinian folktales, its creatures and enchanted sites. Abboud's latest ongoing work (in collaboration with Issa Freij), Hide Your Water from the Sun (2016) is a video and mixed media installation which departs from an essay written by Palestinian Ethnographer Tawfiq Canaan in 1922 about haunted water wells and water demons in Palestine. The artist and filmmaker return to these haunted sites, which have disappeared, in an attempt to experience and document those confiscated territories and tales. O Whale, Don't Swallow Our Moon (2011) is a video of a play scripted by the artist and performed by children where sign language, text, spoon instruments and song convey stories of haunted water wells and springs and their tales. While the installation Taleteller, Talisman, Tree and Stone, Enchanted Creature, Fragmented Bone (2016) shown for the first time, is an assemblage of objects, talismans, drawings, and figurines gathered during years of research and voyaging in the actual and fantastical sites of folk tales and beliefs. The large body of drawings produced since 2005 is a selection from the artist's oeuvre of Palestinian folktales and beliefs. A Happy Ending: Bodies and Beings from Magical Palestine, is an adaptation of an artwork from 2014, made of an installation of balloons which hover on the ceiling and an audio recording of a tale about a ghoul that keeps people's eyes and souls trapped in jars.

***

Dearest,

Throughout our conversations about this exhibition, I have been wanting to ask you a very basic question: What prompted you to start working on Palestinian folktales, studies and archival material? How did you come about studying Tawfiq Canaan "Haunted Wells and Water Demons in Palestine" (1922), which your ongoing project Hide Your Water from the Sun builds on. I also know that one of your other favorite references is 'Speak, Bird Speak Again', which was compiled and edited by two other ethnographers who come from the second wave of Palestinian folkloric studies: Sharif Kanaaneh and Ibrahim Muhawi in 1989. How did you come across those?

I wanted to tell you something I thought about today. I suddenly realized that we spoke about folktales in very different ways: I, as a field of study, and you, as a living and vital world! Perhaps the question we brushed upon today and will return to at the talk with Chiara and Hamza – about what it means to return to folklore today – is not about returning to it as a body of knowledge, but rather as a language to speak with. Perhaps this is where its emancipatory potential lies. In the 1970s and 1980s, Palestinian ethnographers studying the tales and beliefs were hoping that these could form a collective narrative which Palestinians could speak through and resist with. Although I know you have been critical of many aspects of the folktale, such as the roles constructed for female heroines and representations of the Ghoul, the mother, and the bride, which you treated in your video and performance work O Whale, Don't Swallow Our Moon.

I hope the whale won't swallow our moon tonight, because it's full and beautiful, and strange things might happen.

xxx

L.

P.S. Jumana, of course, feel free to ignore parts of the questions/ranting.

***

Sunrise morning dear Lara, full of light,

Where do I begin? Maybe with a direct yes. Yes indeed that is how I approach the tales and my relationship to them (I hadn't realized this before either, not until you pointed it out!); a relationship that goes beyond research and the written word. I have a more personal relationship with the folktales. I suppose an autobiographical one. My understanding or study of the tales is my way of attempting to understand something else: my home, myself, our history, our connection to the homeland, to nature, and to the natural elements. It is a relationship that started when I was a child, a recipient of the tales, of their wonderment and superstitions. In my visual art practice, I return to those tales many years later, only lightly touching upon them from as far back as 2004. My relationship to the tales overall is one that deals greatly with a longing or a desire. A desire to reconnect to a part in me, like a vital organ or a limb, that I have been disconnected from… The tales, in essence, were once a strong part of our lives, believable, told to give us warnings, teach us lessons and morals. As an oral tradition, there can be no denying that even the moment of time when we once gathered to listen to the words being spoken, was in itself a magical moment. We were mesmerized. The tales for us as children, pulled us into a world of happy endings, and despite their gender bias or alternative motives, one thing was certain: they were an invitation to young hearts to love and respect the place they live in. For instance one of the stories I tell in my performance A Happy Ending: Bodies and Beings from Magical Palestine is a great example, have I ever told it to you? Once, just last Tuesday, in a land where thievery and barbarism was allowed, and if one practiced forgetfulness, that too was welcomed; there came into the village of heal yourself a man searching for a wife. Now this man's name is Ma'ruf. No sooner had he entered the village than he came upon a young virgin whose name was Almaza, standing by the well across from El-Ein supermarket. Almaza was weeping and weeping her tears down the well.

'What is it that makes you cry?' he asked her.

'I weep for my lost brothers and cousins. Ma'ruf soon learned that the village Ghoul had imprisoned Almaza's brothers and cousins. Vowing to save them, Ma'ruf jumped into the well, and found the Ghoul in his dwelling, sucking meat off bones.'

'I will devour you next!' exclaimed the hungry Ghoul.

'First, let me give you a gift I have brought you.'

'Alright then, give me your gift and I will devour you after.'

'First, tell me what are these treasures of magic you have here on your shelf? These that sparkle what are they?' asked Ma'ruf.

'They are the eyes of brothers, kept in a jar,'

'And they are the souls of cousins, kept in that jar.'

'This jar stands alone, is it the same?'

'In this jar, I keep my own soul, replied the Ghoul.'

Taking the jar, Ma'ruf threw it on the ground, smashed it and using the magic stick, in one last blow, Ma'ruf hit the Ghoul (once) and the Ghoul was dead. Ma'ruf smashed all the jars, until all eyes and souls were returned to their rightful bodies and all bodies were returned to their rightful homes. Ma'ruf returned to Almaza and they married, all her brothers and cousins attended the large wedding festival that was lavished with love and compassion!

Therefore my return to the tales now as an adult, was firstly because I myself had lost my love for the place I live in. I had lost my connection. The relationship between the earth and myself, its elements, its people, its language, its history and future had become somewhat contaminated, for the many reasons we (Palestinians) all have in common and for many more reasons that only a few of us share.

However, back to your question, in regard to being critical of some of the aspects of the folktale. Yes indeed, the role of women in the tales voiced by women were often discriminatory, a controlling intention, not fun, unless you were the Ghoul in the tale, then you had the most fun: nothing holds you down, your passions are alive. But now that I have been engaged in the project for so many years, I can begin to see things otherwise as well. True, the tales had hidden schemes. True, women have alternate roles (virgin vs mother vs beast), yet I see this now as allegorical for depicting the land itself. I mean, when Issa and I were recently shooting for the film Hide Your Water From the Sun, that is precisely how I experienced the land, as something beautiful, embodying many various characteristics that would cause you to love it or fear it; she could hypnotize you like the mythical sirens, she could crush you and in exchange, she could nourish you and liberate you. In the end, we live with a strong desire for a happy ending with the land, with our right to it too obviously.

By the way, the video / workshop / performance O Whale, Don't Swallow Our Moon, is a project that snuggles so close to my heart, as it marked indeed my initiation into the exploration of the tales.

J.

***

Dearest,

You should know that I was prompted to start reading about folktales and folklore by your projects, and I guess you say this best in your e-mail: folklore is a way to reconnect with the confiscated land, where the stories and the jinns became exiled and we've become estranged because we lost them. We lost our jinns and have become concerned only with documents! (this is actually something you have told me while talking about your adventures searching for the springs and water wells described in Tawfiq Canaan's text). In a sense, we have lost much of our fiction as it is very much connected to site, to land, to matter… And your work brings it back Jumana.

You do make very precise aesthetic decisions in your work, and I always wondered whether these aesthetics also come from folk aesthetics? Also, there are patterns in your work; you worked more than once with children, in videos and performances. In this exhibition for example, all the characters in the video O Whale Don't Swallow Our Moon are children. Why is that? Does it only have to do with them being the biggest audience for the tales? Or is it because they are impressionable and they believe the stories? Also, the drawings, they're almost always very fragile, in every way, in the faint colors, the thinness of the paper, the way they are hung, I always feel so big and clumsy around them...

P.S. Regarding women's representation in the folktales; you remind me of a talk by Sharif Kanaaneh at Sakakini a few months ago, where he said that the folktales are authored, edited and told by women. I guess many of the roles were invented by the women themselves. As you say, the tales carried desires that could not be addressed unless by becoming / performing / transforming into a Ghoul and other creatures.

Kisses,

L.

***

Beauty,

You know the Arabic term 'qaweh albek!' (make your heart strong), used in the times of hardship? I believe this is one of the motives of the tales (back then). They are not a mere source of ideas or a tool to relay messages, but also serve as a source of providing role models (not far from motives of today's tales – the newly emancipated female in today's animated movies!), to lend support and to give the listener a strength of heart. Yes, I work with children, as the style of my drawings, bearing still an innocence, a naivety. Children are great play actors, they loved to take on the forms and characters I envisioned for them. The girl who wore the 'Visit Palestine' as a hat, she represented the character of the homeland. She felt most proud. Working with children teaches a lot.

Everything is fragile around us, perhaps even more so today than at any other time. Perhaps my connection or my return to the tales and their protagonists relates slightly to my need to reconnect to history and to memory - as you say it exactly – you see my work. I feel fragile, and as a result my work comes from my need for strength.

Documents tell us statistics, facts and propose these facts or their consequences. The world of Palestinian folklore does not simply propose. Its characters- person, animal or object- breath in one form and breathe out through another, they live and die countless times as countless faces and names, and these faces and names are all us. I suppose that is also one of my definite attractions in my exploration of the tales: metamorphosis. I mean this is no phenomena only attributed to Palestine. It exists in fairytales and mythologies worldwide. So many of the tales have common elements: water as a source of magic, for example, drinking it will empower or poison. Caves and dark dwellings are beyond a doubt the homes of jinns, goblins and ghouls. All things speak. Heroes and heroines must undergo an adventure, a journey that tests their faith and strength (many "acts" of adventure are replayed with the children in the video O Whale...). And lastly, nothing really ever dies. Here I want to quote from Marina Warner's book Once Upon a Time, in her analysis of fairytales' common elements worldwide in the chapter 'The Magic of Nature' (Oxford University Press, 2014): "...The dead cannot be suppressed; animate forces keep circulating regardless of individual bodies and their misadventures. Even when a tree has been cut down and turned into a table or a spindle, its wood is still alive with the currents of power that charge the forest where it came from."

Do you see Lara? Even with our tales buried behind us, remnants of them still endure today through their currents of power. I could have been satisfied with reading about the tales and drawing inspiration from them, but I could not stop at that. I wanted to touch them. When I am out in the rawness of landscape - and please forgive my romanticism here, I refuse to believe that this oral tradition of ours, with its multi-layered wisdom, humour, moral, magic and superstition, that was so strongly part of our lives, is now not being told any longer through human lips, and had been entirely silenced.

J.

***

Dearest,

I need a tale at the moment to 'tqawih albi"!

The quote from Marina Warner is wonderful, and when I read it I thought that the shrine-like cabinets at the Sakakini where you will place different objects related to the haunted springs and water wells, from those forests and other places are themselves 'magical'. And here perhaps this is a question about art, the object has lost its spirit, and theory has now replaced myth! Actually, in a very theoretical text titled 'The Truth of Art', Boris Groys asks whether art 'is capable of being a medium of truth' [1], as otherwise, it is a question of taste! I will not go into his text now, but I will allow myself to borrow his question...

Is this why you returned to the wells and water springs in Canaan's work? Have the sites themselves given away stories? And here is perhaps a dilemma. If we bring back the stories, are we surrendering to the loss of land? Or are we in a sense returning poetically until we do so physically, especially that those two are so connected, one brings back the other? I guess in your ongoing work Hide Your Water From the Sun, there is an underlying hope, that we have never left in the first place, that our stories still haunt the land, the spirits and jinns have seeped through every crack (they do travel in water!)... If the object retains its 'animate forces' then as long as the land remains, the dead (be it stories or jinns or ancestors) remain as well, waiting, lurking?

***

Habibty,

In olden times, our grandparents, would explain certain phenomena- natural disasters, miscarriages, sickness – through some mythical explanation. Because, they assumed, only some supernatural, superstitious behaviour could be the cause of that which we could not explain. Thus, myth became tales justified and we lived our lives in accordance to these illogical laws. Our way of accepting mystery was by way of allowing an openness to whatever could be the cause of such mystery.

In my work, I want to almost compare and say that, on the one hand the spirits, the tales, their force and their charge, are still alive among us. While on the other, I want to propose that the new faces of the ghouls and demons are the settlers! It is the great ghoul of occupation that now controls our movement, which direction to walk, where to pray, how to love. Occupation does more than just thieve our water sources, our memories, our mythologies (mythologies and memories are life source too). The Palestine of the 1920s, which Dr. Tawfiq wrote and practiced, the Palestine of my grandfather's childhood, of my childhood even – that Palestine, in itself has become somewhat of a myth. Our morality and spirituality was different. Our manners were warmer, kinder. I do not want to repeat the 'poor victim' lamentations here, but we cannot deny what history across the world shows us: the oppressed change as a result of the oppressor's insults. (You see now, I confess the project is not simply related to unlocking a Narnia-like wardrobe from the childhood of Palestine!).

I forgot to tell you how one time while shooting the landscape off a main road near Nablus, a car drove passed us, u-turned back and stopped next to us. The settler driver asked: 'Are you armed?'. He had assumed we were Westerners or Israelis and with that assumption comes the need to protect yourself.

As a written word or list or study, the reader or interpreter gains the necessary historical knowledge, yet is being told how to receive the tales. When one receives the tales through first-hand experience, you hear it as a child or you visit the 'haunted' site you are warned to stay away from (as a child), or you visit the 'sacred' site (as an adult) in order to look for a hidden water source or a tree of the prisoner rooted from the tales and their magic (you will find one in almost every village!). This experience is altogether different!

You know that shot in Hide Your Water From the Sun where one sees robes hanging and swinging from trees in an olive orchard? While Issa and I were filming the site of one of the water springs, where the Fallahin hung the robes there. They did so for several reasons, one of which was to ward off (evil) settlers! From a distance, these robes dance like flying or floating spirits haunting the land!

Oh and by the way, where does the title: Hide Your Water From the Sun come from? Did I tell you? According to the folktales, the most potent water (for healing) is the water that has never seen the light. The jinns and their magic sleep now unrecognised, untold, forgotten, like the water that hides from the sun. Yet it is most powerful of all.

Jumana

[1] Boris Groys, 'The Truth of Art', e-flux Journal #17, (March 2016): http://www.e-flux.com/journal/71/60513/the-truth-of-art/

Jumana Emil Abboud (b. 1971, Shefa-'Amr, Galilee) works with drawing, installation, video and performance, exploring personal and collective memory, loss, longing and belonging, Palestinian folklore, myths and oral histories. Abboud has participated in numerous exhibitions and venues, including the Venice, Sharjah and Istanbul Biennales; the Bahrain National Museum; the Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris; and most recently in a solo exhibition at BALTIC, Gateshead, UK. Based in Jerusalem, she teaches at the International Academy of Art Palestine.

Lara Khaldi is an independent curator, based in Jerusalem. She is a recent alumna of the de Appel curatorial programme, Amsterdam, and the European Graduate School, Switzerland. Khaldi has curated exhibitions and projects in Ramallah, Jerusalem, Cairo, Dubai, Oslo, Brussels and Amsterdam. She teaches at the International Academy of Art Palestine, and at Dar Al-Kalima University College of Arts and Culture in Bethlehem.