Reviews

Invisible Threads

Technology and Its Discontents

On a high wall in the art gallery of NYU Abu Dhabi, the smear of an enormous inked fingerprint trails down the wall. The swipe suggests the action of a thumb on a smart phone refreshing a feed, looking for more to read. Titled Scroll (2014), by Evan Roth, it presides over the sculpture, machine, and installation-based exhibition Invisible Threads: Technology and Its Discontents, presented in the New York University Abu Dhabi's Art Gallery. Curated by the space's associate curator Bana Kattan and artist and NYUAD assistant arts professor Scott Fitzgerald, the show investigates how technology has been considered in art as a concept, a medium, and a format. But also – and perhaps despite itself – the exhibition also demonstrates how the idea of visibility has been fundamentally altered by the ubiquity of technology, both in daily life and contemporary art.

New media work has been seen as a parallel line of enquiry to more mainstream art forms such as painting, installation, and recently performance, as well as subordinate in terms of the money and attention devoted to it. 'New media' itself is a catch-all phrase, comprising a host of different experiments with technology – from computer animation to political projects being mobilized online – and can be roughly defined as a type of work that is invested in new technologies both as form and subject. In the past 10 years, the genre of post-internet art has also looked at new media technologies, but more on their second-order effects: it focuses on the influence of social media on one's subjectivity, for example, or on hyper-real advertising norms enabled by Photoshop. Post-internet work – as its popularity with the market, overlaps with fashion (particularly in the collective DIS, who curated this summer's contentious Berlin Biennial), and the co-option of corporate marketing-speak suggest – has not been shy about occupying a central position in terms of money, attention, and art world power.

This is the background against which to read Invisible Threads, and it feels difficult to gauge this show without thinking through the impact of an artwork's contextualization. Yet, the curators did little by way of signalling these shifting fault-lines. Ironically, this lack of contextualization places the show within a very post-internet critique: the idea that the artwork's circulation helps determine its very meaning or political potential. And so, a work of art – as with Roth's Scroll – is not just a smear down a high wall, but an index of its tradition.

Invisible Threads takes as its premise the idea of making the invisible processes of technology visible: flashing green lights on five wall-mounted servers, for example, signal the interception of data from nearby WiFi signals in Addie Wagenknecht's XXXX.XXX (2014). Phillip Stearns presents A Chandelier for One of Many Possible Ends (2014): an installation of white neon bars that lights up every time a receptor detects radioactivity in the air. This move to make information visible has been a crucial part of technologically focused art since 1960s cybernetics, which explored how input entered into a machine in one form emerges in another, and which enacted the different steps this process could take. It has also often been submitted as a form of politics: if we could just see the technology, as the thinking goes, we could understand the forces that act upon us. Visibility functions in this sense as consciousness-raising, bringing hidden power structures – whether they be technological or governmental – to light. Wagenknecht's XXXX.XXX reveals the extent of surveillance, directing our attention to the frequency of the interception of our emails and internet searches.

However, in the newly emerging genre of post-internet art and other recent reactions to technologies, the status of visibility is reversed. Projects focus instead on the exchangeability of the image, or the fact that any image could be any other image at any time – visibility as a mode of radical flux, rather than the idea that the visualization of information is a conduit towards knowledge. One of the featured works, Like (2014) by Siebren Versteeg, presents an algorithm that mimics the endless painting of an abstract canvas. Every sixty seconds, this digital painting is uploaded to Google Image search, and its nearest match appears on the split screen opposite. The work challenges ideas of authorship, originality, and craft, dramatizing instead an endless cycling of different representations.

Invisible Threads puts these two separate moments side-by-side. It makes for a useful display of the current moment, but also, in its weddedness to visualization as a mode of political promise, feels a little out of date. Stearns's revelations about radioactivity in the atmosphere are at most gestural: what are we really supposed to do with this information at hand? Stripped of the political valences that are given to the visualization of information within a new-media context, the work simply feels operatic. And it is hard, now, to think of technology as formally as new-media work often does; the iPhone, for example, is not just a feat of user input and technology but a site of deep affective and monetary relations, keeping us in contact with others and allowing companies such as Facebook or Snapchat to demand and receive more of our time. The Kuwaiti artist Monira al Qadiri's sculptures of iridescent oil drill bits, Spectrum 2 (2015), exemplified such a broad-range critique in the show, showing miniaturized oil-drill bits as not simply items of technology but the pearly basis of the UAE's ambitions for itself as a nation.

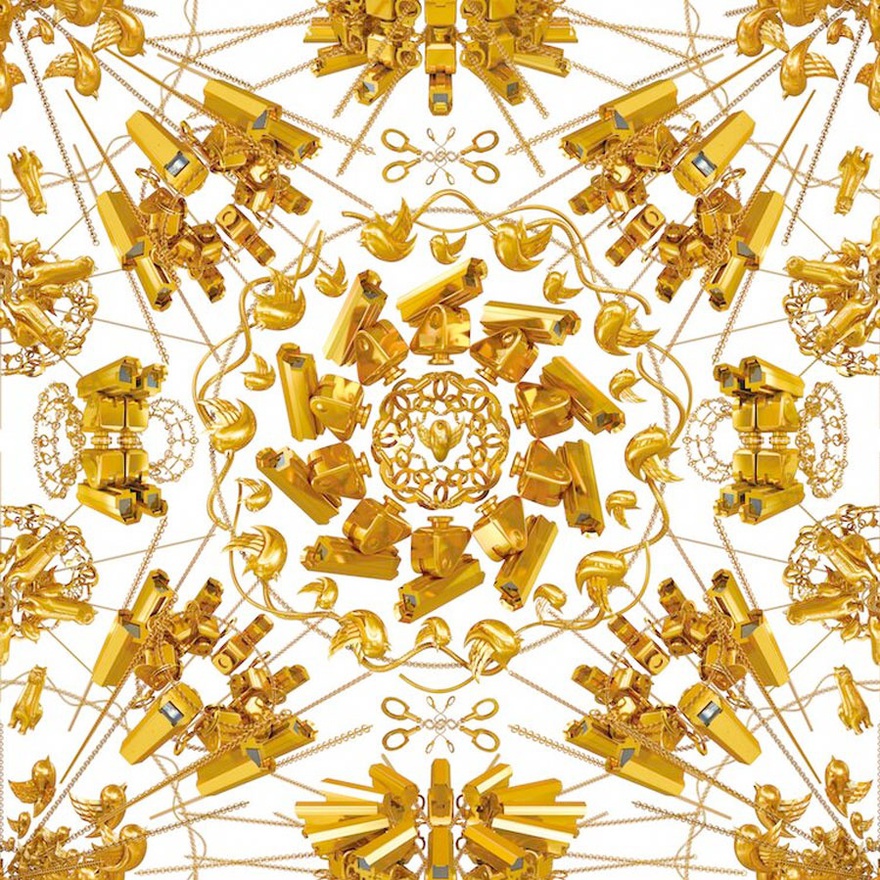

At the same time, historical new-media and net.art work often stand for a moment of political purity that post-internet, in getting into bed with the market, has forfeited. This was a key argument, for example, in the latest issue of Spike that assessed net.art vis-à-vis post-internet work. We could look here at the wallpaper piece by Ai Weiwei in Invisible Threads, titled The Animal That Looks Like a Llama but Really Is an Alpaca (2015), that is a repeated motif of surveillance cameras, handcuffs, and the Twitter icon, all emblazoned in gold and arrayed in geometric patterns. The work points to the danger of posting information on social media to show how Instagram and Twitter comments could later be used as evidence against oneself. It's also tantalizingly sly: installed as flashy wallpaper it essentially functions as a selfie backdrop station-daring people to pose for social media even against a warning of the threat of doing so.

Though it is about circulation, The Animal That Looks Like a Llama but Really Is an Alpaca was loaned with the stipulation that visitors could not take pictures of the work on its own; a standard request that is intended to mitigate the spread of subpar mobile-phone pictures of artworks. (His galleries and his studio must limit the circulation of his images so they retain their monetary value This means that NYUAD's vigilant gallery guards had to jump in to stop anyone snapping a self-less image of the work: a performance of an – indeed, invisible – network of capital and power that Ai Weiwei and his works sit on.

As new media has long known, there is always more than meets the eye. Invisible Threads is poised between two modes of new-media and contemporary art, offering a timely exploration of how the different networks of the art world – whether a work is destined for Documenta, an electronic arts festival, or the home of a collector (or all three) – affect the interpretation of their concerns.