Reviews

Recalling the Future

Post-Revolutionary Iranian Art at SOAS

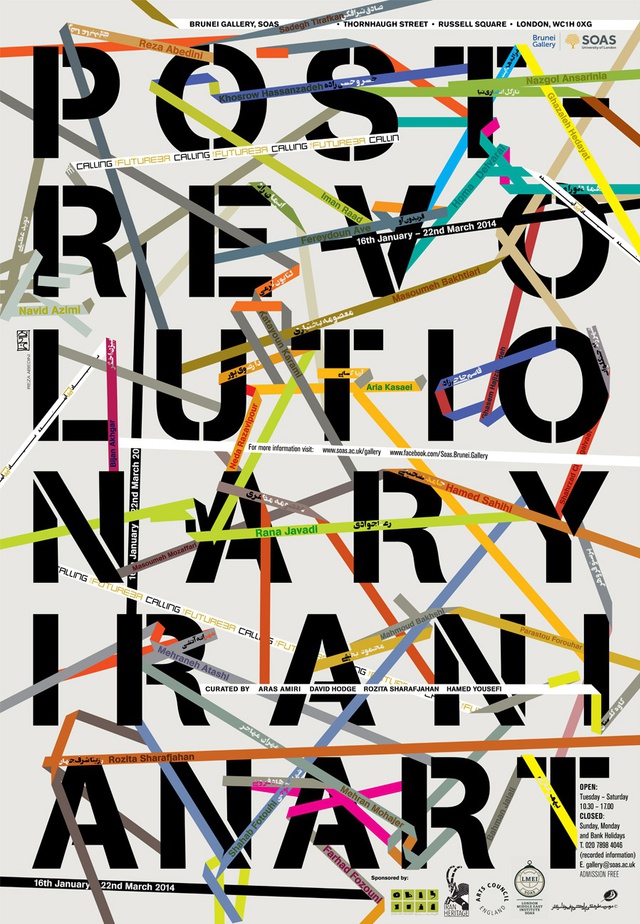

Prior to the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi implemented state-sponsored artistic policies that promoted modernism and interaction with the western world, which were in line with his political ambitions. Thus, the new Islamic Republic naturally brought forth a new set of artistic doctrines that reflected anti-west, pro-Islamic policies[1] – a synthesis of modern and traditional with a focus on political and cultural independence that has since been termed 'neotraditionalism'.[2] The recent exhibition at the School of Oriental and African Studies' Brunei Gallery, titled Recalling the Future: Post-Revolutionary Iranian Art, was curated as a rejection of such fixed, state-imposed ideas on art practice. It featured artworks by 29 Iranian artists, many who were exhibiting in the UK for the first time.

The exhibition began with a large banner viewable as one entered the exhibition space, which stated the following: 'Recalling the Future'. It is worth pondering this declaration. 'Future' appears to be a trigger word in the art world at the moment, and particularly in reference to the Middle East and its immediate neighbours.[3] This interest in the future is intended to posit and deconstruct ideas of how past lessons can be used to create a better future.[4] Although the exhibition seeks to present art produced since the 1979 revolution (although, in fact, it also shows pre-revolution photographs and predominantly shows works made in the last ten years), one cannot help but feel that the use of the word 'post-revolutionary' has been utilized so as to capitalize on the recent western interest in 'post-revolutionary' art from the Middle East.

Beside the exhibition banner to the left was a window into the ground floor gallery space, a peek into the 'future' of which one was about to enter. To the right was the curious installation of helium balloons by Parastou Forouhar entitled Surrender (2014). In the distance, one could hear the faint, haunted singing of Shahab Fotouhi's video installation Repeat After Me (2008). Here, one could instantly pre-empt the wide range of media featured in the exhibition, purposefully intended to speak to the diversity of art coming out of Iran today.

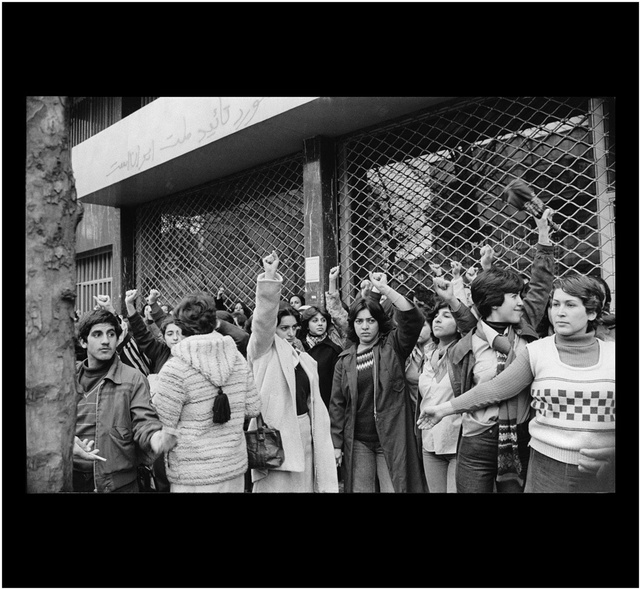

There was an issue of layout and flow in this exhibition, which was naturally constricted by the three-level space available at the Brunei Gallery. For example, the display of documentary photography by Kaveh Golestan, Rana Javadi and Bahman Jalali – described as providing 'historical background to the post-revolutionary art displayed in Recalling the Future' – was located on the first floor and therefore was easily missed or at least considered only after one had already seen the exhibitions' other works. On the other hand, the ground floor gallery space of the exhibition was partitioned into two distinct areas – a main room, which included mostly photographic and installation works – and an enclosed room featuring Mehraneh Atashi's Tehran's Self Portrait series (2008-2010). This physical separation complimented Atashi's photographic series, which explored the rapidly growing city of Tehran in terms of the contradictions and ambiguities found at the borders of private and public spaces.

Downstairs, the space contained varied works, including a selection of mixed-media images from influential early post-revolution artists Ghasem Hajizadeh, Fereydoun Ave and Masoumeh Mozaffari, as well as examples of Iranian graphic design and works around the themes of gender and class. A separate room at the centre of the space contained four highly political installations by Shahab Fotouhi and Parastou Forouhar, including Fotouhi's Can I Speak to the Manager (2008), which accurately embodied and highlighted the issue of Iran's political entanglement within the field of art. The piece was made up of six drawings on felt, each depicting the emblem of the republic at various stages of representation, as if awaiting a draughtsman to complete the image. The overly complicated process presented in Fotouhi's work perfectly articulated state bureaucracy even within the realms of the aesthetic.

The ground floor presented the theme of urbanism and the negotiation of one's identity within a modern, dynamic environment. Nazgol Ansarinia's installation Fabrications (2013) included two 3D architectural models accompanied by photographs of murals on buildings in Tehran. The models, created using a 3D printer, were the real life embodiment of the 'imagined' buildings that have been created through the recent government-sponsored murals around Tehran, covering building facades with idyllic images of pre-modern, traditional Iranian architecture. The 3D models juxtaposed both modern and traditional buildings resulting in impossible, absurd spaces that represented the existing contradiction between nostalgia and the ever-changing reality of the city. The piece was particularly interesting in the context of this show not only for its use of state-of-the-art equipment, but also for the conceptualization of Tehran as seen both through the eyes of the state's 'imagined' vision as well as the people's realistic view. Here, the artist literally demonstrated how possible it is 'to intervene within these processes [of national identity building], and re-route them towards new constructions of one's own making'.[5]

While this exhibition succeeded in introducing an otherwise uninformed public to the wide variety of art coming out of Iran, it did so rather incoherently by conflating themes of national identity and artistic practice in a suboptimal space. However, there was no doubt that the overarching theme of this exhibition was that of diversity – in media and in subject – and this in itself accomplished the stated goal of dispelling the idea of a single Iranian artistic canon.

This exhibition is guest curated by Aras Amiri, David Hodge, Hamed Yousefi, and Rozita Sharafjahan and ran from 16 January – 22 March 2014.

[1] For more information on this subject, see: Daria Kirsanova, 'Articulating Dissensus: Contemporary Artistic Practice in Iran at a Revolutionary Moment', Ibraaz, 28 August 2013 http://www.ibraaz.org/essays/72.

[2] Hamid Keshmirshekan, 'Discourses on Postrevolutionary Iranian Art: Neotraditionalism during the 1990s', Muqarnas 23 (2006): 131-157 http://www.jstor.org/stable/25482440.

[3] Future of a Promise (Arab exhibition at Venice Biennale 2011); 'Future Imperfect' (Ibraaz at the Tate, 2013); Future Now: Iraq and Contemporary Art (Cornerhouse Gallery, Cairo, 2010); not to mention other non-Middle East-specific art events focussing on the future such as Nostalgic for the Future (Lisson Gallery, 2013/14); Future: The Human Factor (Southbank Centre, 2014); Future and Reality (5th Beijing International Art Biennale, 2012); 'Archives for the Future' (Art and Visual Culture Conference, London, 2014); and the reoccurring The Future Can Wait show (last on during Frieze 2013).

[4] 'This Week's Six Pillars Show – Post-Revolutionary Art Exhibition', 6 Pillars website, 13 February 2014 http://sixpillars.org/2014/02/13/this-weeks-six-pillars-show-post-revolutionary-art-exhibition/.

[5] 'Recalling The Future: post revolutionary Iranian art', SOAS University website http://www.soas.ac.uk/gallery/recallingthefuture/.