Reviews

Accented

Maraya Art Centre

'What is the connection of our accent to our citizenship?' the artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan asked an audience proficient in toggling between Arabic and English at Art Dubai's annual Global Art Forum in March 2015. He may have been hinting at the linguistic-political conditions of the Forum's host city, Dubai, where a throng of working-class cadences swarm outside the bounds of Emirati citizenship. But more pointedly, Abu Hamdan was referring to a twenty-first century form of shibboleth – forensic examinations of audio recordings whereby European border control agencies screen asylum seekers' backgrounds by analysing not their stories, but their accents.

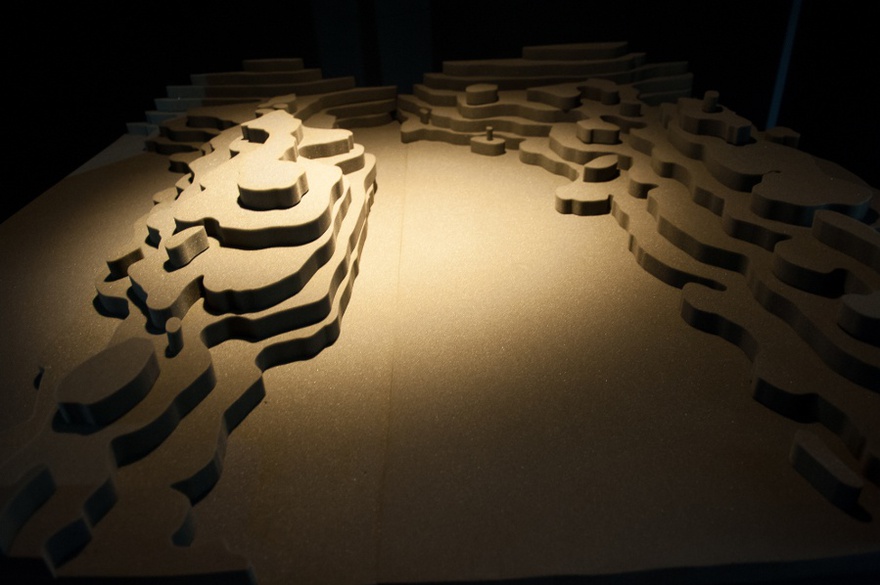

Abu Hamdan's incisive remarks at the Global Art Forum could simultaneously be heard, together with testimony from lawyers, phoneticians, and asylum seekers, as part of his audio-installation The Freedom of Speech Itself (2012) presented at Sharjah's Maraya Art Centre as part of group exhibition Accented (1 March–15 May 2015). Channelling the geopolitics of sound into tactile experience in a room darkened by closed curtains and furnished with the sculptural forms of voiceprints, the installation stood as the centrepiece of the show, which features 15 artists and collectives engaging with the politics of language, migration, labour, and globalization. The works on display in Accented plumb the many connotations of the accent, literally illustrating the fault lines of enunciation – Pouran Jinchi's drawings, for example, feature only the diacritical marks in a Quran verse – or more broadly representing forms of vernacular that resist translation and exchange.

For show curator Murtaza Vali, the accent symbolizes a defiant holdout against global forces of standardization. In his catalogue essay, 'Searching for the Voice of Difference', Vali writes:

While the processes of globalization promise homogenization, transparency and translation across cultures, the accent-localized in and expressed through the body-represents the residue or remainder that challenges these claims. … It is what exceeds language, resists assimilation and remains opaque.

Vali's appeal to opacity resonates with the late Martinican theorist Édouard Glissant's defence of créolité, in essays like 'Transparency and Opacity' and 'The Right to Opacity', as a collectively shaped and locally evolving tongue contesting the imposition of French. In Vali's exhibition, the accent, following postcolonial theories that assert linguistic hybridity as subversive of European imperialism, stands as an embodied glitch within a global neoliberal system whose lingua franca is 'business English' promulgated by corporate media.

Refreshingly, Accented does not find alternatives to the monoculture of Siri and CNN in reversions to the traditional or the analogue, but rather by articulating a contemporary poetics of plurality. Jaret Vadera's videos, for example, cleverly extract corporeal and anecdotal qualities from the most monolithic of web sources. Vadera's File_Not_Found (2013), a one-minute succession of screenshots apparently captured from Google Images, presents a brief narrative of individual mortality ('One day I will die…') by matching each word with a tangentially related image, converting the algorithmic search task into an idiosyncratic exercise in association.

Many of the works in this exhibition, which features artists hailing from across the Middle East and south Asia, explore the tensions inherent in defining the 'accent' of the Gulf, a region divided between its global image and its far more diverse local character. A miniature model by the GCC collective, Figure B: Micro Council (2013), epitomizes this problem simply, by simulating the table at which the collective's namesake negotiates. The elegant furniture is subtly inflected with a few regional elements, but its largely generic aesthetic is aimed at projecting affluence and authority to dissolve cultural difference. Ammar Al Attar reveals a similar dichotomy by photographing prayer rooms throughout the UAE. A rift emerges, in these pictures, between the airport-like universality of the décor in Mirdif City Center, Dubai (2012) and the distinct, varied atmospheres of spaces photographed in Sharjah.

There is a welcome playfulness in several of the pieces on show, which use humour and surprise to political ends. Farah Al Qasimi's quirky photographs slyly undermine symbols of globalization, spotlighting the shadow of McDonalds' iconic arch as it fades into a dust-covered wall in Old McDonalds' Sign (2014), and focusing on a sandcastle model of the Dubai skyline while cropping the actual skyscrapers in the background in Broken Sandcastles (2014). Raja'a Khalid's Oud Aura (2015) riffs on the industrial manufacture of local authenticity by installing a digital device that emits a synthetically produced scent of oud – a perfume associated with Gulf tradition – into the gallery space. Monira Al Qadiri's eight-minute video, SOAP (2014),stitches together clips of soap operas produced in the Gulf, but injects these melodramatic scenes of domestic discontent and moral impropriety, often centred on a controlling patriarch, with roughly collaged images of the migrant women and men whose labour keeps sumptuous homes clean and elite families fed. As art-world attention remains focused on protests around the Guggenheim and other cultural institutions under construction on Abu Dhabi's Saadiyat Island, Al Qadiri's video is significant in complementing a campaign waged primarily through the political tools of negotiation, boycott and direct action with the viral-ready aesthetics of pop-culture satire.

Though whimsical at times, Accented is densely discursive, including as one of its works a commissioned volume of the Dubai-based cultural journal The State. The elegantly designed Syntax Freezone, which features eight essays centred on language in the Gulf,includes a meditation on Kerala-Gulf relations that describes the complex sounds and characters of Malayalam, a report on speech therapy services for the deaf in Dubai and a remarkable piece examining North-South divisions within Italy that is punctuated by instructions for performing Italian sign language. The volume opens by returning to a question that editors Rahel Aima and Ahmad Makia posed in the publication's first issue, in 2012: 'How do you speak from a place, or a non-place? Who speaks, and in whose vernacular?'

It is these far-reaching questions that undergird Accented and the answers are nothing if not contradictory. Advancing the accent as a sign of ungovernable cultural singularity, Vali concludes his catalogue essay with the optimistic declaration, paraphrasing postcolonial theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, that if the subaltern cannot speak in recognizable words, perhaps she will be heard for the deviant sound of her voice. But Abu Hamdan's The Freedom of Speech Itself, which Vali aptly designates a 'counterpoint' to much of the exhibition, locates technologies of domination that target precisely the linguistic markers that The State's editors label 'sites – and cites – of resistance'. Accents, while sustaining the relational, the local, and the historical against the grey sheen of global capital, may grant the subaltern the right to be heard only so that she may be screened, classified and deported.