Essays

The Shadow Economies of Being Seen

Determining the Axis of the Global South and Middle East

Imposed upon their varied and ever-shifting populations, the descriptors Global South and Middle East connote a world of directional flows. In this sense, their constituent parts are made navigable through compass points for orientation, largely figured semantically and expressed in the imagination of those looking in. These modular entities are fashioned and perpetuated as a cohesive buttress to their ratified presence as coordinates on an axis, ensuring a mutual flow of geopolitical cooperation, antagonism, and trade. Conveniently for contemporary cultural practitioners, to explore the conflicting spatial paradigms and mobile subjectivities between these two regional coordinates is to reveal visual hierarchies that mimic the dimensions of the Cartesian system of three-dimensional space.[1] Mutually inductive to vertical-horizontal linear motion as to nonlinear rotation, the geopolitical application of an axis implies a nucleus, a fixed body, and infers the dynamic circulatory power of the object.[2]

My aim in what follows is to explore the interrelated points of departure and arrival that delineate the axis of Global South and Middle East. We begin with an absence, in this case of a point of orientation with which to navigate the networks of intercultural communication between these two regional coordinates. Certainly it was a similar lack of horizon that Hito Steyerl defined as, 'the departure of a stable paradigm of orientation, which has situated concepts of subject and object, of time and space, throughout modernity.'[3] By contrast, one stable horizon has long prevailed between the two entities; that is the one-way horizontality of the qibla, the direction of prayer, and thus of Mecca – formerly Jerusalem – and pilgrimage. To this linear flow of the literal passage of time, the semantic employment of spatial metaphors for quantifying time, we can add the horizontal return ticket of labour migration to the oil-rich states of the Gulf.

Framing Petro-Islam and Labor Pilgrimages.

The large-scale migration from the Global South to the Gulf States of the Middle East that gathered steam in the 1970s was in part homologous with the routes taken by pilgrims making the Hajj. Yemenites, Pakistanis, formative Bangladeshis, Indonesians – and, it must be noted, many non-Muslims although substantially fewer Latin and Central Americans – gravitated towards the Gulf. Propelled by the embargo on the sale of oil to the USA in 1973 in protest over American support for Israel, petroleum infrastructure grew exponentially and the Middle East became the new terminus for mass labour migration from South Asia and parts of South East Asia.[4]

Preceding, following, and consumed as mementos of their labour pilgrimages, many Muslims of South Asia bought, produced, and disseminated a distinctly vernacular image of the Middle East in Muslim South Asia. Both Jürgen Wasim Frembgen and Yousuf Saeed have produced monographs detailing the poster art and populist visuality of South Asian devotional Islamic imagery. While not as ubiquitous as the chromolithograph embodiments of Hindu gods, Islamic poster prints segue Mecca and Medina into the shrines of Sufi saints through the spatial imaging of lenticular printing. These images provide a surrogate of travel between local mosque and Kaaba and manifest a startling sense of depth across a printed image. Perhaps allowing for the animation of a short segment or performing looped highlights of a travelogue as a transformation between two or more viewpoints, lenticular prints are actualized though a subtle tilt of the print. Islamic lenticular prints largely express a worldly transformation, from here to there, rather than enacting miracles or apparitions as in the Christian canon of lenticularity. Instead, Islamic poster art in South Asia perform and embody a desire to make, or experience making, pilgrimage. This shifted horizon is a corporeal appeal to the possibility of travel or transformation on a global Islamic axis around which a transnational body circumambulates.

Yousuf Saeed connects the pervasive influence of Saudi oil wealth in Pakistan to the condemnation of populist imagery, importing instead a sanitized form of Islam imported from Arabia. He calls this a 'homogenous Arabization',[5] which seeks to discourage grave worship and sever the ability for objects to act as intercessors between man and God. Benedict Anderson's stately and much-cited 'Imagined Communities'carries throughout the motif of the secular pilgrimage from metropole to colony that in the colonial era demarcated, administered and effectively traced the spatial realities of future nationalisms.[6] Islamic poster art and lenticular prints enact the reverse operation; they reorder the temporal and geopolitical visual hierarchy and enact the buried impulse of the verb hajja (to intend to make pilgrimage), allowing those unable to enact the Hajj to perform it instead. Farida Batool has explored the ability for lenticular printing to perform a surrogate of travel and conspire in the transformation of the horizon, the projected point of orientation.[7] As a widely consumed method of visualizing mental travel within and between the global Islamic community, the ridged topography of the lenticular print deserves a wider practice-based reappraisal in line with the transformation undergone by the form of miniature painting in Pakistan in the early 1990s. During the military dictatorship of Zia al-Huq, the reduction in scale in Pakistani painting occurred as a calculated retreat from the bombastic militarism of sanctioned styles.[8] Imran Qureshi, Aisha Khalid, and Shahzia Sikander are just a few of the well-known cohort of students who benefited from the institutionalization of miniature painting in the National College of Art in Lahore under the tutelage of Professor Bashir Ahmed.

The contemporary miniature revival's most successful progenitor to date has been Shahzia Sikander, whose works of intense artistic toil often act as a surrogate for themes of labour exchange. Her film Parallax (2013), previewed at the Sharjah Biennial of that year, was concerned with mobile workers drawn as fodder to the gushing and transformative power of oil wealth. Having lately begun to expand the scale of her miniatures through multi-channel animated installations in a state of constant flux, Sikander's Parallax views the contemporary Emirati Gulf as a sedentary community in opposition to the enforced mobility of its expansive foreign workforce. In the preparatory research for the work, the artist drove from Sharjah to Khor Fakkan, noticing along the way the proliferation of archaic oil technology that punctuated the desert, now tired talismans of societal transformation. Another work emerged from this journey, The cypress is, despite its freedom, held captive by the garden (2012), when the artist met a Pakistani guard who had travelled as a migrant worker in 1976 and had risen from builder, to manager, to solitary guard of the cinema in his 36 years working in the building. Originally designed by architects based on Karachi cinema styles, Sikander's eulogy to the dilapidated cinema is expressed through large-scale projections that, like the outmoded architectonics of the cinema, operate as a framing device which foregrounds the immutable form of the solitary labourer.

In TJ Demos' study 'The Migrant Image' the author supplants and softens the experience of exilic dislocation in favour of restoring the cultural entanglements of demographic change, mental travel, and the mobile lives of artistic practitioners. While the generative qualities of migration are familiar to most, Demos' crucial insight comes by identifying 'opacity as a politics of imperceptibility'.[9] Seizing upon Édouard Glissant, Demos describes opacity as that which obscures knowledge, 'where one would expect anthropological insights and cultural access… there is only blankness and disorientation'.[10] This sense of disorientation, of free-fall, of surrendered horizons, eulogizes the migratory entanglements that run parallel to Sikander's own life as a mobile art-worker. Dwarfing both infrastructure and architecture, to call Sikander's projections works of opacity would be vulgar; they retrace the horizontal journeys from embodied source to imagined destination.

In the realm of political science, Gilles Kepel finds the transnational investment in infrastructure: the foundation of madrassas, and the proliferation of Saudi-built mosques from Karachi to Jakarta, a direct correlation to the Pan-Arabism of Nasser's Egypt. But this time,

for the first time in 14 centuries, the same books (as well as cassettes) could be found from one end of the Umma [pan-Islamic religious community] to the other; all came from the same Saudi distribution circuits, as part of an identical corpus. Its very limited number of titles hewed to the same doctrinal line and excluded other currents of thought that had formerly been part of a more pluralistic Islam.[11]

Crucially for non-Arab nation-states, the strands of pan-Arab nationalism was loosely substituted for Kepel's definition of petro-Islam, effectively changing the visual iconography of nascent nations like Pakistan, whose vernacular Islamic architectural traditions were transformed into an 'international style' of marble and green neon lighting.[12] Most importantly, petro-Islam encouraged migrant workers returning from their labour pilgrimage to redraw the identity structures of the region, taking as their model the new king-makers of globalization; Saudi Arabia, whose natural gift was seen as a divine reward for their distinct brand of Wahhabi piety.

Verticality and the Calculus of War

A homologous visual hierarchy to that which visualizes, performs, and subsumes the migrant worker, has been identified by Judith Butler who, in a recent lecture at the London School of Economies discussed various biopolitical strands related to the act of voluntary and involuntary human shielding. This enforced hierarchization appeals to the international image of actors in conflict and, while legally extraneous to the sphere of war, operates as a part of what Butler calls the 'the economic calculus of a warzone'.[13] By gauging the value of human life, this calculus also refers to the migrant experience and draws us again to sites of dispersal and sources of labour. In the same way that the migrant worker wagers that their pilgrimage will end in ultimate return, improved wealth, and social standing, so too does the refiguring of the citizen as human shield include the wager that the enemy will not wish to indulge in the reciprocation of a war crime. But instead of operating horizontally, with the orientation of a fixed horizon, human shields are discerned from above, party to a wager of vertical vision.

Butler's recent proposal builds on the works of Eyal Weizman and Banu Bargu and responds largely to the various wars in Gaza, but is equally responsive to acts of involuntary human shielding enforced by Daesh (ISIS) in Iraq, Bashar al-Assad in Syria, and the late Gaddafi in Libya. Weizman's early-twenty-first century essay The Politics of Verticality[14] identified the need for a new discursive understanding of territory for governing, peace making, and defending the Palestinian and Israeli lands as a vertical and subterranean topography. To govern for the peace as well as the war Israel maintained control of both the skies and the underworld, without either appearing on political or military maps. Verticality is not only a project of three-dimensional imaging and surveillance but of spatial mapping and discernibility. Steyerl's less academic and more discursive practice imagined a fall into a haze of disorientation as the product of lack of a stable horizon, one in which the horizontal process of orienting oneself on a fixed point throws into disarray the linear evolution of Euclidean space. Elaborating Weizman's thesis, Steyerl declares that 'Vertical sovereignty splits space into stacked horizontal layers', and that a politics of verticality 'promises no community, but a shifting formation.'[15]

Beirut-based artist Akram Zaatari's recent film and video installation Letter to a Refusing Pilot (2013) articulates the spatial re-orientation of a historical horizon. Zaatari excavates a rumour from his hometown of Saida which details how, following a bombing raid during the 1982 war, an Israeli pilot refused to bomb his school, choosing instead to drop his bombs in the sea. Many years later Zaatari, founder of the Arab Image Foundation and an artist whose excavation of archival objects plays a key role in his craft, managed to meet the pilot who refused to the bomb the school. Key to making the decision not to strike his intended target was the Israeli pilot's prior training an as architect able to discern a civilian structure. His architectural training also contributed to his de-militarization, with Zaatari suggesting architecture was key to the pilot's 'becoming civilian'.[16] Furthermore, Zaatari's own background in architecture underlines the importance of the ability to discern objects and their societal function from a temporal or spatially removed distance, in this case, from above.

Zaatari can be considered part of a generation of Lebanese artists who intermingle architectural practice with performance-lectures, assemblages of found objects and ephemera to explore the built space of collective memory. Tony Chakar, a contemporary of Zaatari, has produced an evocative and deeply personal body of work that reads Beirut as an intangible space of arrivals and departures. Presented in the form of encounters that are largely transient – lectures, walking tours, and testimonies – Chakar's work attempts to freeze the historical image as it flares up. A short speech intended for delivery at Documenta 12 Magazines transregional meeting in Hong Kong in 2006, which the artist was unable to attend due to the ongoing Israeli offensive, is worth quoting at length:

…both the Israeli army and Hezbollah fighters were using modernist maps made of Cartesian points and precise coordinates, one more efficient than the other. They both shared the same conception of space: an absolute space of mathematics and geometry, a space with no place for allegorical time or existential memories. In such a space both are not unimportant, they simply have no place to be. The Israeli army and the Hezbollah fighters were both victims of modernity's biggest project: the geometrization of the world.[17]

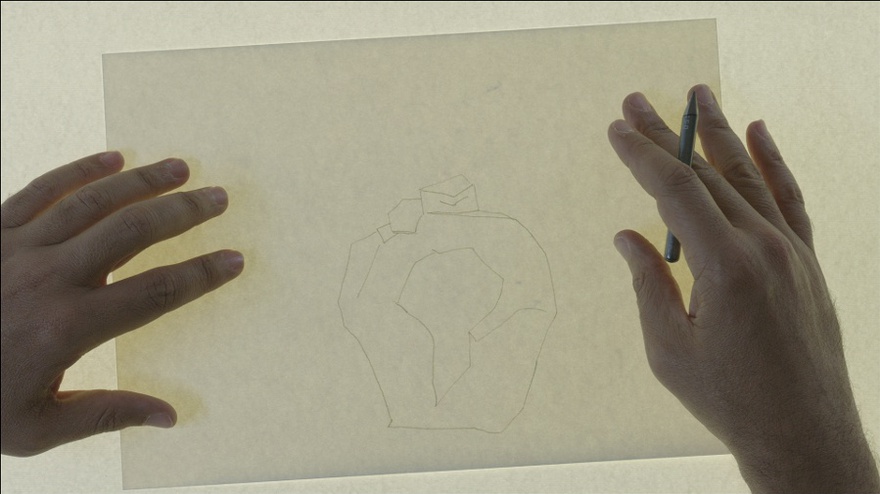

Letter to a Refusing Pilot begins with a drone-mounted camera ascending and surveying the surrounding environs of Saida some 30 years after the aborted bombing. The act of refusal carries enough gestural weight that the fact the school was bombed only hours later by a second more willing pilot is glossed over. Immediately the drone footage juxtaposes two different visualities: the first intensive, high resolution, mobile, malleable, perversely democratic; the second – that of the refusing pilot performed in correspondence – through a roving hand that occasionally dons white gloves for handling and excavating 'archival' evidence of Saida's photographic and architectural history. The hand sketches imagined vertical perspectives, preluding the construction of paper planes that accompany the filmic 'letter' on its journey of correspondence.

Kasim Abid's eloquent and measured inter-city symphony Whispers of the Cities (2013) is composed of footage shot from a high angle, usually a hotel window. Captured in Ramallah during the Second Intifada, Baghdad during and after the invasion, and Erbil, this quiet polemic is patiently figured through the lens of everyday life. High above the city, construction workers who barely flinch at the sound of machine gun fire share the vantage point of the artist, if not their sense of precariousness. Abid's peon to the rhythms of conflict seizes upon the ubiquity of automobiles as an uncanny but startling highlight, documenting repeated attempts at reconstruction and cycles of labour. The solitary policeman who struggles to control the flow of traffic acts as an ideal symbol and intermediary of the flow of the auto-mobile pedestrian.

With Abid silent but ever-present behind the camera, hints of surveillance quickly dissipate in the opening Ramallah section, when both cars and pedestrians are cleared for imposition of curfew and tyre-spikes are placed in the road. The enclosure of the filmmaker no longer appears voluntary and less like a voyeuristic eye than a political act of penetration. But Abid's presence is merely a relational conduit that connects these cities. In these zones of conflict, an embodied vertical perspective is a politicized tool able to capture the movement of military vehicles from a vantage point, restoring citizenry to those submitted to the calculus of war, to the 'geometrization of the world'. Abid's work highlights the very status of being watched, quantified, and submitted to the shadow economies of being seen, while laying bare the hierarchy of those bodies without cars, those peddling products to drivers, and labourers involved in infrastructural development, however benign or innocuous.

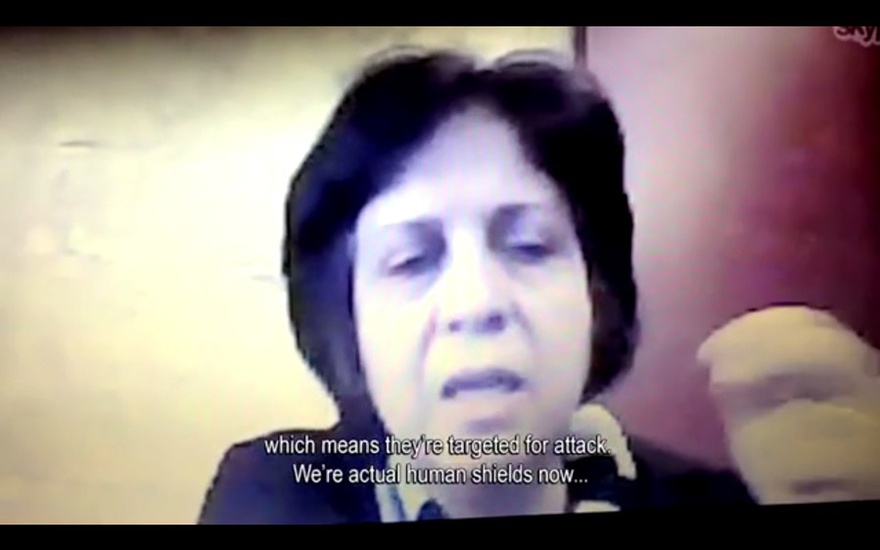

Most illustrative of the forced submission of involuntary subjects to the 'economic calculus of a warzone' are the protagonists in Liwaa Yazji's debut film Haunted (2014). Yazji's nine subjects, all Syrian residents in a constant state of readiness to flee, ruminate on the immovability of their homes, the psycho-geographic traces of what has already been left behind, and the imminence of departure. Yazji's protagonists confess their temptations to consume everything in their home, to destroy everything, to box and label everything for an imagined return or to dissuade potential looters, while remaining preoccupied with the fate of the space after their departure. The lives of an older couple in Damascus dominate focus. Speaking with Yazji over Skype, yet only three kilometres away, the fraught and intensely vital pair acknowledge their own presence as human shields, unable as they are to leave their home due to the panopticon of snipers and the ever redrawn lines of control beyond the confines of their apartment block. Humming over the grainy footage the sounds of Skype sonorously demarcate layers of distance, and the telescopic reach of the camera stretches further than Abid's comfort zone into the territory of indiscernibility, into the realm of Trevor Paglen's long-distance photographs of covert military installations. While many conflict documentaries naturally perpetuate the demarcation between military and civilian actors, Yazji's presentation of her subjects reflects the condition of individuals where that distinction has been effectively eradicated. By challenging the discernibility of that seen through a snipers lens, sovereign verticality is for a moment symbolically refuted.

Visibility Machines

A wager is in evidence in both the promise of return, and the commitment to pilgrimage. The antagonists of Judith Butler's polemic against involuntary human shielding partake in a dual wager and extortion, gambling on the reluctance of a military adversary to engage in a war crime. Judith Butler's elaboration of the legal implication of weaponizing the war crime has its roots in a recent study of voluntary human shielding by Banu Bargu. Bargu locates the emergence of asymmetrical forms of warfare, waged from afar, that have instilled the impression that warfare itself has become 'decorporealized'.[18] This distinctly biopolitical management of sovereign warfare is articulated as such to appeal to the imagined moral spectators of globalization who are asked to consciously hierarchize the value of bodies of citizens in conflict areas. Fittingly, the hierarchization of bodies is also correlative to Hito Steyerl's 'class system' of image value, which identifies at the bottom rung the degraded 'poor image' whose 'lack of resolution attests to their appropriation and displacement.'[19] By treating the body as military material, human shields become decorporealized in the same way that those sans-papiers are rendered diplomatically invisible, with Butler noting that human shields are made profoundly visible only when their deaths make them collateral damage.

This essay sought to address the ways in which actors in the theatre of war, religion, and commerce extend operations of transnational biopower over those of other nations. Discernibility and imperceptibility are equally key processes in Butler's definition of the calculus of conflict. The greatly divergent moving image works detailed herein – and the South Asian vernacular souvenirs of intended pilgrimage – frame the body politic of the Middle East and the Global South along an axis of projected control. In the possibilities for dissent dormant in the subtle tilt of the lenticular print, their elaboration by Farida Batool, the mutable counter-histories of Shahzia Sikander, Akram Zaatari's civilian architectonics, Kasim Abid's sedentary symphony, and Liwaa Yazji's peon to the civilian, can be found the angle of deviation; obliquity, a moral diversion that takes the coordinates off-grid. For the interrogation of the gravitational pull of oil infrastructure employment, the demarcated direction of prayer, and the circumambulatory rotation of bodies around the Kaaba, as well as the vertical sovereignties of bombers, drones, and reimagined maps, an axial tilt is crucial for cultural practitioners grappling with trans-cultural classifications like Middle East and Global South.

In the case of his appearance coinciding with the 2013 Istanbul Biennial, Trevor Paglen proffered aerospace engineering for aerospace engineering's sake, challenging spatio-economic politics and the role of surveillance in the public sphere. Prototype for a Nonfunctional Satellite (Design 4; Build 3) (2013), saw a four-metre tall model for an orbital spacecraft that utilized technologies normally associated with militarism and surveillance, squashed into an automobile repair garage. Not designed for use, this nonfunctional satellite was a product of Paglen's 'de-militarization of fields of knowledge'.[20] This poignant and essential process helps us to deviate from the ominous path that leads to forecasted projects such as the EU-funded 'Project SUNNY',[21] which plans to implement UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) for the maritime surveillance of coastal migrants. These automated monitors will de-militarize verticality in a way that subsumes migrants to the 'economic calculus of a warzone'. While the research is yet to address the legal issue of airspace sovereignty crucial to Weizman's discourse, the ever-increasing asymmetry of vision and the ongoing annexation of bodies, serves to further fortify the axis of vertical and horizontal control for which the imposed entitles of the Global South and Middle East are but a microcosm.

[1] René Descartes, Discourse on Method, Optics, Geometry, and Meteorology trans. Paul J. Olscamp (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2001).

[2] Politically, the application of this symbol seems to have been first employed by Mussolini, whose attempt to broker a Weimar Berlin-Rome Axis aimed to buttress international uproar over D'Annunzio's fascist heterotopia of Fiume.

[3] Hito Steyerl,'In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective,' e-flux, 2011 www.e-flux.com/journal/in-free-fall-a-thought-experiment-on-vertical-perspective/.

[4] To take a sample, today the number of Pakistani expatriates in Saudi Arabia alone stands at 1.5 million. By 2013 the United Arab Emirates – population 9.2 million – had accumulated the fifth largest base of international migrants, with those from the Indian subcontinent comprising 90 per cent of a total of 7.8 million migrants.

[5] Yousuf Saeed, Muslim Devotional Art in India (Oxford: Routledge, 2012), p. 7.

[6] Benedict Anderson, Imagined communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London and New York: Verso Books, 2006), pp. 54-55.

[7] Pakistani artist Farida Batool has eloquently explored the ability for lenticular printing to perform a surrogate of travel and conspire in the transformation of the horizon, the projected point of orientation.

[8] Salima Hashmi, Unveiling the Visible: Lives and Works of Women Artists of Pakistan (Islamabad: ActionAid Pakistan, 2002), pp. 9-11.

[9] T.J. Demos, The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary during Global Crisis (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2013), p.246.

[10] T.J Demos, 'The Right to Opacity: On the Otolith Group's Nervus Rerum,' October 129 (2009,): p. 113.

[11] Gilles Kepel, Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam (London: IB Tauris, 2006), p. 72.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Judith Butler, 'Human Shield,' LSE Law, LRIL and OUP present the London Review of International Law Annual Lecture (London, UK), 4 February 2015.

[14] Eyal Weizman, 'The Politics of Verticality,' OpenDemocracy, 23 April 2002 www.opendemocracy.net/ecology-politicsverticality/article_801.jsp.

[15] Steyerl, op. cit.

[16] Author interview with Akram Zaatari, Feburary 2014.

[17] Tony Chakar, '…To the Ends of the Earth,' written for the Documenta 12 Magazines Transregional Meeting in Hong Kong, held on September 10-14 2006 and read in place of Chakar who did not attend.

[18] Banu Bargu, 'Human Shields,' Contemporary Political Theory 12.4 (2013): pp. 277-295.

[19] Hito Steyerl, 'On Defense of the Poor Image,' e-flux, 2009 http://www.e-flux.com/journal/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/.

[20] Trevor Paglen on Aesthetics, Ibraaz Talks, 24 October 2013, http://www.ibraaz.org/channel/15.

[21] For more information, see: http://www.sunnyproject.eu/.