Essays

Mindful Body

An Introduction to Body Art and Performance in the Gulf

It's strange how the sense of touch, infinitely less precious to men of vision,

becomes at critical moments our main grip with reality, if not the only.

– Vladimir Nabokov

Mind and body are strictly connected in each and every individual, as they obviously pertain to dimensions characterized by intersections, territorial invasions, and communications. The mind can perceive, it can experience through the body, it can even force the body into certain directions, influencing its natural development. Yet, as connected as they are, the mind seems to indiscriminately prevail over the body, because of a kind of supremacy that many would allegedly recognize in it. Nevertheless, it could not be any more surprising to discover that the body can deeply influence the mind as well, inhibiting or propelling its energy and its polarity. Both the mind and the body can be – in alternate ways – catalysts; both can act as magnets that induce, or direct, behaviours in a delicate and ever changing balance between eye and limb.

This connection has reflections on a larger scale, as we move from the individual to the social dimension and try to see the regulators of human interactions. How much do political and religious directives determine social phenomenon, in both their physical and mental consequences and expressions? In which proportion is mass media (a mental construction) influencing our physical desires (subliminally) and self-opinion (trying to comply to the dictate of stereotypes)? These are just few of the many questions we could ask about the determination of general, social behavioural patterns induced over the collective bodies and minds, or the 'public body'.

When we think of the preponderance of the body over the mind we do, perhaps naively and with misconceptions, think of a sort of animalism – a form of resistance embraced by the most spontaneous, unrefined, rebellious aspects of human personalities. Performance is often using the body to its extreme potential, tying it or liberating it, thus marking a point against fixed, over-structured, or judgemental positions. Through the use of the body we tend to create a break in a continuum by physically intervening in the 'reality'. At the same time we mostly invite the audience (both the one attending the performance and the one who will come to know it through the documentation of the event – a critical and often carefully set aspect of the performative action) to make contact, to have a 'tactile' experience where the limits of the bodies tend to fade and to encourage an encounter. The spectator is asked to 'attend' or, in other words, a tension is to be created in order to pass the message. Space and time become conspicuous elements, and their variation determines a variation in the result of the single event. The response by the audience can become an essential component of the performance, always to a certain extension and within certain limits since the artistic intervention mostly has a status by itself, as a manifestation.

It should be noted that performance art in the Gulf does not often happen with an audience gathering at a set place, date and time. It is more often a solitary action, sometimes attended by few friends also acting as technical supporters assisting and documenting the event that is later proposed as a documentary act. The public, instead of being a direct witness, is a voyeur encouraged by the artists themselves.

In fact, the terminology adopted to describe such happenings or performances in the Gulf region, and the appeal to the mental, spiritual, and emotional sphere brought about through the physical gestures offered to an audience by the performer, somehow evokes and recalls a mystic experience: the audience enters a door which was closed and gains access to another dimension, is exposed to a perspective, and witnesses an action that can be surprising, annoying, shocking, disturbing, engaging, or intriguing. The performer can induce a heightened, sensorial experience of our world, even subverting it, if for a moment, for the audience that experiences the intervention. In this experience, the senses of the audience are undeniably put under stress, although many performances are cerebral and tend to communicate on a purely mental level rather than on a physical one. Nevertheless, a sense of distress and a questioning is activated by the performative intervention, particularly in a context like the Gulf where performance remains an un-experienced artistic expression.

Throughout the Gulf region, there is a need to define the terminology surrounding performance, since confusion permeates this sphere of artistic creation. In most cases, if not all, the performances created within the GCC region relate directly to an understanding of the body and they can be divided into a few main categories: body and space (such as Hassan Sharif and Abdullah Al Saadi); body and political/social issues (for example Noor Al-Bastaki, Anas Al-Shaikh, and Tarek Al-Ghoussein); and body and gender (for instance Ebtisam AbdulAziz, Waheeda Malullah, and Shaikha Al Mazrou). Body art is one of the possible manifestations of performance in this context; one of the ways privileged by artists engaging with the body, though it is not a synonym for performance in a strict sense. 'The term "body art" is not only art historical one, but rather a more anthropological one and as such implies using the body as a support for painting, piercing, and so on,' explained Leigh Markopoulos, Chair of the graduate programme in Curatorial Practice located on the San Francisco campus of the California College of the Arts, in a conversation. 'The use of the body in contemporary art theory is more or less strictly related to "performance art."'[1]

The use of the body as a physical support that properly responds to the definition of 'body art' is also represented by artists active in the Gulf region, such as Budoor Al Riyami and Rabi Georges. To cite just few cases, Hassan Sharif's Walking No.1 (1982) and Jumping No.2 (1983), which were performed with virtually no audience, exemplify the interaction with the natural context and the adoption of an act as simple as that of moving in the space as an apology of artistic purpose and mission. In Anas Al-Shaikh's My Land, 2 (2009), a defiant position to the political use of sectarianism is firmly embodied by pairing the Bahraini flag, a national symbol par excellence, with the bare back of the artist performing a traditional sea song. Ebtissam AbdulAziz's Women's Circles (2010) addresses gender issues and questions women's role in society, with specific reference to the restrictions imposed by Middle Eastern societies.

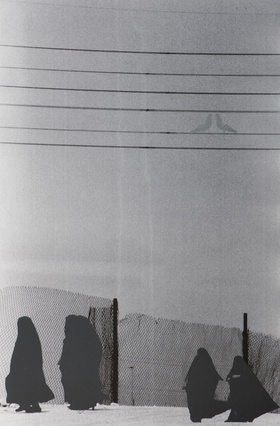

Another group of works represented in the region tend to use the body as a subject in a more linear, narrative way, or respond to a desire for illustration, such as Manal Al Dowayan. In her Landscape of the Mind series (2009), the artist reflects upon the very concept of landscape and its interrelation with people and the impossible dialogue that is visually created – a surreal context that ultimately addresses stereotypes and misconceptions. This approach is not strictly pertaining to performance, but what is of interest here are the many ways in which artists from the Gulf have approached performance as a kind of body art, and the ways they have used the body not only to relate to and incorporate the world but to perceive and represent the bodies of others, observing and projecting over another subject the relation that runs between the social corpus and the individual. The mind propels the body to become art in order to move the minds and bodies of those who witness the gesture.

Le corps découvert. Discovered body [2]

A few years ago, a major exhibition curated by Philippe Cardinal and Hoda Makram-Ebeid and held at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, focused on the body in Arab art.[3] The most attention was paid to painting, with an extension to photography and, to a certain extent, to sculpture and video art. In their introductory essay, the curators synthetically trace a time frame for the discovery of live painting – the practice of painting a model, often nude, that started with the beginning of the 'grand tour'[4] in Europe. This journey characterizes the first encounters with Western artistic traditions for a number of Lebanese, Syrian and Egyptian artists since the late nineteenth century.

Regardless of the fact that this exercise had been incorporated long ago into the practice and education of Middle Eastern painters, interest in the body has shown a remarkable increase since the beginning of the 1980s, not only as a subject to be represented but also as a tool for exploring the surrounding world. In spite of the well-known and oft-recalled Islamic fundamental stipulation that forbids the representation of any animated creature (both human and animal), since the first dynasties, starting with the Umayyad, a series of socio-cultural factors have worked in favour of figurative representation – a representation that has always existed in Persia, India, Constantinople, and in the whole Ottoman Empire, even on the general level of the civil society.[5] Regardless of its predilection for abstraction, Islamic art, and Arab art in particular, is not totally contrary to animated representation provided that it remains within the limits of decency; a circumstance that is mostly respected.[6]

There is indeed a profound difference between portraiture and performance; between portraiture and the use of body conceived as a vehicle to explore 'more than simply the body' but an amplified dimension often referring to socio-political issues. The question here is about the different degrees of involvement required by the representation of the body – a passive practice, I would say, as often witnessed also in modern Arab painting compared to the active use of the body through performance. Performance evokes and refers to multiple aspects that, though often unmentioned, permeate the sense of the action and its happening.

The late 2000s witnessed an increased interest in the masculine/male body, often through photography that seemed to be at the edge between documentary and art, thus inscribing itself in a line that is well represented by the rich archive of the Arab Image Foundation.[7] Qatar-based artist Georges Awde's photographs from the series Quiet Crossings (2008–2010) explore the delicate question of the relationships existing between men in eastern society, including that of latent and/or declared homosexuality, a social taboo covertly approached and mentioned. Similarly, the theme of the male body appears, although tinted with a more tortured humorous note, in Moroccan-French artist Mehdi-Georges Lahlou's works Tango de Compose (2010–14) and Mouvement décomposé (2011), where she raises questions pertaining to identity, sexuality and the freedom of a sort of bodily self-determination. In the video Camaraderie (2009) by Egyptian artist Mahmoud Khaled, as well as the work Les Hammams de Sana'a (2010) by Nabil Boutros, 'the impact of social codes over the everyday life' is explored.[8] In these works, the representation of the body stages and approaches issues of self-perception, sex and desire, aiming to address an even more universal theme – that of Arab identity and the identity of the individual within the Arab world, circumscribed in a moment in history that is characterised by a growing, and often overpowering, globalization.

This tendency and theme in Arab contemporary art is very recent. Traditionally, and with few exceptions – among them: Lebanese painters Khalil Saleeby, Deux nus (c.1901); Habib Srour, Nu (1898); Daoud Corm, Untitled (1917); or Iraqi Abdul Qadir al-Rassam, Portrait de Mohamed Darouich Al Allousi (1924). In the Gulf, before Hassan Sharif's Portrait series (1981) and Mohammed Kazem's sketches from 1998; Bahraini painters Abdulla Al Muharraqi and Ahmed Baqer; Kuwaiti sculptors Issa Saqer and Sami Mohammad; and Emiratis Najat Makki, Abdul Qader al Rais and Abdul Raheem Salem, the representation of the body consisted only of the representation of the woman's body - body per excellence – by male artists, a pure object of aesthetic pleasure or the object of pure aesthetic pleasure. It is only since the 1970s that women artists also started representing their own bodies, the feminine body, often animated by an evident intent to re-appropriate a territory that entirely belongs to them, and to push its limits farther than commonly permitted in the direction of self-emancipation. In the early works of Lebanese artist Huguette Caland (especially the series Self Portrait paintings from the 1970s), the body is reduced to a line, deprived of all sexual allusion, representing an assertion and a claim for self-definition; Ghada Amer, with her celebrated use of embroidery transferred from the domestic sphere to the public one, approaches the crude representation of women's bodies in pornographic literature in Le champ de marguerites, (2011), a male oriented universe where the body is reified;[9] whilst Lamia Ziadé, in her works Zarif, Hamra, Tabaris (2008) and Pigalle, mousse, tissu (2008), re-appropriates and crudely exhibits the intimacy and the sexual and erotic attributes of women's bodies in a feminist sort of abstraction and synthesis not deprived of a certain self-irony.

In a so-called male dominated universe, women artists from the Arab world had finally appropriated all the expressive means and used them to position themselves and reverse the clichés that they had traditionally been imprisoned by, and to a certain extent still are.

The Political Body

Although this current in Arab contemporary visual arts has often been emphasized, the treatment of the body by contemporary artists from the Arab world not only questions issues of individual and collective identity, with special regard to gender, but also and recurrently deals with the political implications of the use of the body. The political dimension that was largely omitted during the 1980s – not only in the visual arts – has since become a renewed source of interest and inspiration. If, in its most successful formation, the body is used as 'means and aesthetic mediation', sometimes the level of involvement and political engagement reaches and attains the condition of a 'militant' statement that can ultimately weaken the artistic relevance of the work.[10] As art critic Farid Zahi notes:

The body is transformed in a symbolic and visible capital… a means of transgression, of subversion and calls into question metaphysical, ethical and generic as well as political dichotomies. It abandons the status of simple matter and it rises as the masterly context for a strategy of creation, invention and intervention. In this sense, the invisible is embodied in the visible, not the contrary.[11]

Among the most recurrent themes widely explored in different areas and regions of that fictitious yet compact dimension denominated 'the Arab world' are: the condition of women, religious fundamentalism, war and its consequences, freedom of expression (with a special, although not exclusive, attention to the physical or geographical sphere), sexuality, the fight for emancipation and the aspiration for a political and social change, the awakening of awareness about environmental issues, but also a more universal and existentialist approach to the themes of the relation of the self and the space, about the potentialities and limitations of the body, the role of individuals within the setting to which they belong, and the very idea of belonging.

Similarly to a number of female artists of her generation, Algerian-French artist Zoulikha Bouabdellah often symbolically works on feminist issues, thus claiming on behalf of women the right to face and react against the traditional religious and cultural establishment.[12] The migrant condition that many artists, just like their compatriots, have embraced is a powerful and recurrent element in artistic production from the Arab world and the diaspora. Diaspora is a term that is appropriately applied to the Palestinian population but that could be shaded and adapted to other countries as well, as a social and de facto phenomenon if not as the result of a political constraint. This cultural confrontation between eastern and western, the dialectics created between traditional models and occidental perspectives, and the unequal balance of these two constitutive conditions is often represented in works by Arab artists. In her video Dansons (2003), Bouabdellah performs an oriental dance to the hymn of La Marseillaise, the French national anthem. Her hips are covered with the French flag, thus performing and raising questions relating to notions of belonging, cultural integration and exoticism - an allegation that eastern societies still struggle to shake off and continue to fight against.

Born in France to Algerian parents and now based in London, Zineb Sedira situates herself against this confusion. She is often ably overridden by Arab women artists who obtain an 'easy' popularity in Western countries by emphasizing clichés around the veil. In her photographic triptych Self Portrait or the Trinity (2000), Sedira shows women standing, turning their backs to the spectator at different angles. The women are completely veiled in white, creating a dissonance with the traditional black veil worn by women in the Arab world. The use of the colour white, as well as the adoption of an iconographic format proper to Western painting, such as the triptych (which was, as well as the polyptych, widely adopted and almost exclusively used to support religious representations during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries [13]), bridges the two cultures and integrates them in the apparent aim of emphasizing the common aspects of the different monotheistic religions instead of forcing the undeniable cultural differences that distinguish them.

Through the adoption of a technique that explicitly refers to collage (and that may fall in the field of 'kitsch') and the use of materials from different contexts (textiles, clippings, beads, paper dolls and so on), Lebanese artist Zena El Khalil's practice ironically addresses subjects of war and violence. The characters sourced from magazines and showing the typical traits of macho behaviour, as seen in the series But I can't let go (2008) for example, are disguised by El Khalil and contaminated doll-like attributes that incisively contrast with the rifles and guns they are charged with. This absurd contraposition powerfully reveals the juxtaposition of diametrically opposed stimuli and components in our daily lives and is profoundly imbued with comics and the channel-flicking television culture that permeates the younger generations, in both eastern and western countries.[14]

Body and Space: Performance and Land Art

The performative action requires space and time to happen. It needs a physical place more than a determined chronological setting, unless it is inscribed in strict spatial and temporal coordinates. Performance art seems to have more than just a few aspects in common with land art, or Earth art as its practitioners have also described it. The relationship between the space where the performance is set and the physical consistency of the performance itself can sometimes indicate a sense of prevalence of the space over the action (especially in performances set in the desert such as those by Hassan Sharif, Tarek Al-Ghoussein, and Noor Al-Bastaki). The documentation of performances attributes a large proportion to physical space, in which[15]> the physical involvement of the artist is minimal, as if they were using the performative action as a tool for abstracting the body as an individual presence.[16] Here, I mention again Hassan Sharif's Walking No.1 and Jumping No.2 where the action, already minimal in its consistency, is almost absorbed by the space where the performance takes place, thus reducing the human figure to a mere illusion. The staging of the performance does not reflect an attitude of reverence towards nature but rather a consideration of the role of humanity in a wider horizon.

With regard to their relationship with the environment, some of the land artists active during the late 1960s and early 1970s have discovered in the simple action of walking a tool for a symbolic transformation of landscape and territory. A physical presence in the environment does not appear to be necessary any more and instead it frequently results in a superficial, reversible action that does not profoundly affect the earth. This characterisation can also be found in a number of performances where the intervention consists of a single action that does not physically affect the environment in the sense of introducing any tangible change. The trace left behind by the land artist (see as the iconic example Richard Long, A Line Made by Walking, 1967) is the presence of an absence and at the same time the witness of a passage.

As such, the body becomes a tool - an instrument for measuring time and space. An emblematic performance in this sense is Hassan Sharif's Body and Square (1983) where the artist draws a grid on the floor, which he then occupies with various poses and different angles, thus utilizing the body as a tool for interacting with the spatial construct. This idea is best demonstrated in Sharif's performances realized in 1982–1984. It is also evident in Mohammed Kazem's performative actions and some of his other projects, including Photographs with Flags (1997) and Directions (Steps) (2012) where the body is used as a metre, an element of comparison over which the perception of reality is calculated and re-regulated; and in Abdullah Al Saadi's Naked Sweet Potato (2000–10) and his trips in the mountains, circumnavigations that are documented by his drawings and diaries, just like ancient travellers used to do.[17]

Arguably, one of the main problems with the act of walking as art is the transmission of the experience in an aesthetic manner; this concern is also shared by the performative action. In both land art and performance art, documentation is an essential aspect of the action – an appendix on which the intervention relies on for its survival.[18] The physical space, either as a natural or manipulated landscape, as well as the time of the intervention become relevant and this happens with special regard to the documentation and its elaboration a posteriori. The documentation becomes a structural component of the performance alongside the walk of artists in land art, closely linking the concept of a performative action to its documentation.

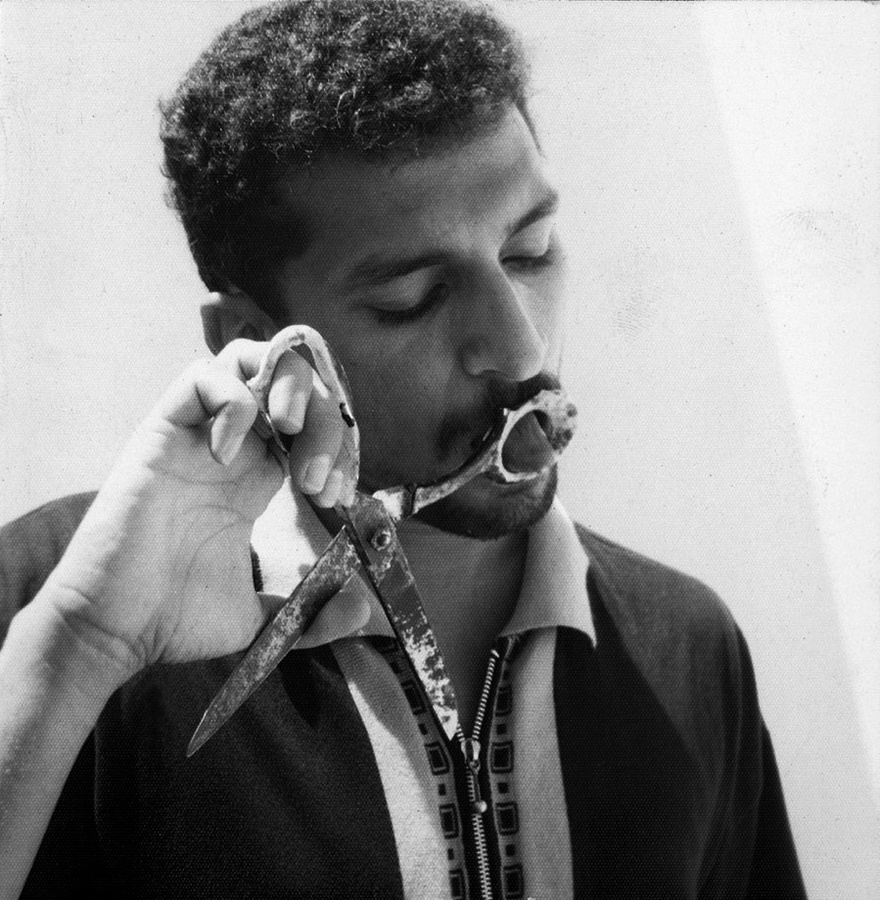

As noted before, most of the performances realized in the Gulf since the early 1980s have been unattended, private events in which only a few friends participated who were also responsible for documentation. Such is the case with Hassan Sharif's performances in the Hatta desert, where a small group including his brother, artist Hussain Sharif, were present and took charge of photographing the event (which is the only available documentation, as the action was not filmed). Other examples include Mohammed Kazem's photographic series Tongue (1994), Legs and Arms (1995), Showering (1998), and Walking (1996), and the first set of images belonging to Photographs with Flags;[19]and Abdullah Al Saadi's video Naked Sweet Potato,[20] which was filmed by the artist and staged as a solitary presence in the natural environment, one that was slightly and temporarily affected by the artistic action and that then returned to its original status almost without the trace of a passage.

A slightly different situation is represented by Tarek Al-Ghoussein's photographs, where the performative intention lies more implicitly than in the aforementioned works.[21] Here, the posture he impersonates, the choice of the landscape acting as a theatrical scenography, along with the other situational coordinates (time, light, proportion and interaction of space and body and so on) are carefully set and the shooting immortalizes the hic et nunc, or the specificity of a moment that aims to symbolize a condition.[22] The same approach characterizes Bahrain-based Anas Al-Shaikh's performances, both recorded in the landscape and in an interior, where the action is neatly documented in a 'pressurized' space, ready to metaphorically explode as soon as it is exported.[23] In fact, here again the artist works alone, setting the scene and developing the action both in the case of photo and video documentation, which is carefully planned in order to witness and circulate an event deprived of a physical audience. Bahraini artist Waheeda Malullah inscribes herself in this current as she films and photographs actions performed by other actors, therefore calibrating and controlling the two moments – both the moment of action as well as the successive one represented by the documentation that will result from this intervention.

Performances staged in interior or closed spaces, including Mohammed Kazem's Hands and Legs, Anas Al-Shaikh's My Land, 2, and Ebtisam AbdulAziz' Women's Circles, counterpace those staged outdoors in exterior sites and seem to reply to themselves in a more self-contemplative, existentialist and even narcissistic way.[24] A few specific cases of this can be seen in Emirati artist Nujoom Al Ghanem's Between Heaven and Earth, the Body I Borrowed (1994) and German-Syrian Rabi Georges' performance You Shall Not Boil Your Child in Your Mother's Milk, where a high, almost physical level of excitement is palpable. In the latter, performance once again retains its full meaning by implying a set time and a defined space where the public is invited to attend the 'manifestation' of the artist, disguised, transfigured and engaging in an action that will result in a physical trace in the space (a pavement covered with salt, a circle made of ink…) and most likely in an emotional one in the public's memory. Al Ghanem stages an almost theatrical action, where the bodily aspect and its interaction with the 'other' and with the context imply a narration.

It is not inconsequential that Al Ghanem is, above all, a poet – a consideration than can be extended to other participating artists. This perhaps simply reflects a certain complexity surrounding and permeating the field of contemporary visual arts, where multiple levels of crossover between disciplines are increasingly and remarkably imposing a different model of dialectics. The oneiric landscapes created by Saudi Arabian Manal Al Dowayan in the series Landscapes of the Mind, for example, seem to somehow represent a folding – but a folding forward and outside – to expand the neatness of her previous and celebrated series I Am (2005–07), where the commingling of western and eastern elements in a highly-staged context and pose refer to a prise en charge (taking control) by women without hesitations about their role in society. In this series, the pregnancy of the meaning is intellectual, referring and connecting to an underlying layer that subtly resonates in the public's mind.

The Represented Body

The representation of the body during the first half of the twentieth century moves from an almost pathological interest in bodily posture, the way it occupies the space, and the way it relates to the viewer, to the look:

the glance of painters and sculptors (for example in the literary texts of Khalil Gibran with his ethereal bodies, or Mahmoud Moukhtar's sculptures of allegoric bodies, Inji Aflatoun's and Mohammad Rawas' sketched bodies), who represent the body as a body, an absolutely a-historical body, out of context, generally immobile, integer and integral, for a pure aesthetic pleasure, an almost erotic joy or a moral edification."[25].

This is largely due to the possibilities offered by photography, which had recently been included in the arts and was soon adopted and practiced by Middle Easterners including Farid Haddad, Armand, and Asaad Arabi, amongst others.

We find a similar approach from the poet and artist Mohammed Al Mazrouei, where the representation of the body is abstracted and purely delineated, yet bears a universal meaning synthesized in his compositions and in the silhouettes that he traces, with significant fragments of reality.[26]

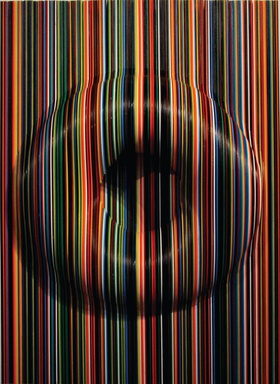

A sculptural translation of this approach is represented by Shaikha Al Mazrou's piece Inside Out (2013) that along with Untitled (2012) harmonizes multiple themes and tensions, resolving them in an apparently purely cerebral exercise. In fact, these works are characterized by an open defiance of the optical perception of the surrounding dimensions we are immersed in. The physical illusion embodied by these works imposes a reconsideration of the very meaning of perspective of the position which bodies occupy in space and in society: their virtual disappearance as well as their full incarnation.

Besides the formal elements in the use of the body in performance throughout the Gulf region, there is a recurrence of certain 'humanistic positions', depending on the way artists have positioned themselves with respect to the body. The artist's own body can be perceived as a tool for exploring reality, in a quest for universalism, where the individual embodies the humanity and the simplicity of his/her actions testifying to a more inherent pertinence and reference to the human condition per se.[27] Artists have also used the body, their own as well as a transferable one, to analyse and explore the social, political and environmental reality they are imbued with and that they happen to be surrounded by and live in.[28] [29] Another element to take into consideration is that of the expressive limitations still prevailing in the Gulf. This aspect has a considerable influence on the formal solutions opted for in creative terms. Besides, a consistent group of works produced in the Middle East are quite contextual as they treat subjects that are specific to a certain condition and context, more specifically referring to local or regional issues and situations. They might need an explanation if 'exported' to a different context while they speak by themselves if presented in their original one. This can be limiting, but widely responds to a need to stand tall and courageously in front of the world, often with grace, mostly without shouting, as both these qualities are a passport to acceptance and their opposites a magnet for censorship.

[1] I would like to thank Leigh Markopoulos, Chair of the Graduate in Curatorial Practice located on the San Francisco campus of the California College of the Arts, for her precious advice and for the conversation we had concerning the terminology and the definition of the field of intervention from which this project has originated and developed.

[2] The title of this chapter refers to and depends significantly upon the contents of the homonymous exhibition Le corps découvert, Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris, 27 March–15 July 2012. The exhibition offered an overview on the representation, depiction and use of body in modern and contemporary art from the Arab World. See: www.imarabe.org/exposition-ima-4735

[4] Grand Tour was the traditional trip of Europe undertaken by mainly upper-class European young men of means, or those of more humble origin who could find a sponsor. The custom flourished from about 1660 until the advent of large-scale rail transport in the 1840s, and was associated with a standard itinerary. It served as an educational rite of passage. (Wikipedia, Grand Tour) 'Beginning in the late sixteenth century, it became fashionable for young aristocrats to visit Paris, Venice, Florence, and above all Rome, as the culmination of their classical education. Thus was born the idea of the Grand Tour, a practice which introduced Englishmen, Germans, Scandinavians, and also Americans to the art and culture of France and Italy for the next 300 years. Travel was arduous and costly throughout the period, possible only for a privileged class-the same that produced gentleman scientists, authors, antiquaries, and patrons of the arts.' Jean Sorabella, 'The Grand Tour', The Met Museum website, October 2003, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grtr/hd_grtr.htm.

[5] 'Although the letter has long taken the place of the body [...] the body has been present in modern art through two exemplary attitudes: a strong expressionist representation of its ontological drops (the body is transfigured, stripped of his membership of gender, brutalized and violated in its canonical aspect: the expressionist body seems to want to make a critical vision of being and the human condition) and a symbolic representation (the body is in this case support and material, sacred and spiritual verticality).' Farid Zahi, 'Au-delà du masculin et du feminin: le corps et ses enjeux dans l'art contemporain arabe', in Le corps découvert, exhibition catalogue (Paris: Hazan and Institut du monde arabe, 2012), pp. 135-143

.

[6] Here I refer to and widely draw upon the essay: Salah Stétié, 'Le corps en supplement', in Le corps découvert, exhibition catalogue (Paris: Hazan and Institut du monde arabe, 2012), pp. 23-35.

[7] See: Monia Abdallah, 'L'Orient des photographes', in Le corps découvert, exhibition catalogue (Paris: Hazan and Institut du monde arabe, 2012), pp. 180-185 and see: www.fai.org.lb.

[8] Ibid., p. 194.

[9] 'By opting for the female activity par excellence, Ghada Amer [...] refuses to join the front fightof the feminist struggle, but uses trickery and docility to open us up to a cleverly creative world that focuses on the subtle subversion', Translated from French by the author. Mohamed Rachdi, 'L'implication effective et symbolique du corps', in Le corps découvert, exhibition catalogue (Paris: Hazan and Institut du monde arabe, 2012), pp. 151-167.

[10] Zahi, op cit., p. 140.

[11] 'Le corps se transforme en capitale symbolique et visible … moyen de transgression, de subversion et de remise en cause des dichotomies tant métaphysiques, étiques, génériques que politiques. Il cesse d'etre simple matière pour s'ériger comme le lieu magistral d'une stratégie de création, d'invention et d'intervention. Ainsi l'invisible s'incorpore dans le visible, non le contraire.' Ibid., p. 142.

[12] For this section I am largely indebted to Rachdi, op cit., pp. 151-167.

[13] See Simone Martini (c.1315), Pietro Lorenzetti (c.1280–1348), Gentile da Fabriano (c.1370–1427), Masaccio (c.1401–1428) or Andrea Mantegna (1431–1506), just to name a few among the Italian artists using the formal solution of triptychs and polyptychs.

[14] 'Comme beaucoup d'artistes de sa génération, cette artiste est marquée par les univers télévisuels et internet caractérisés par le zapping et autres télescopages d'images parfois des plus contradictoires.' Rachdi, op cit., p. 164.

[15] The case of Anas Al-Shaikh seems to be different because of the way the space references the body and vice versa. The photographic cutting in the documentation seems to clearly suggest a predominance of the human action over the landscape, a focus that is mainly dedicated to the human experience of the space.

[16] The case of Anas Al-Shaikh seems to be different because of the way the space references the body and vice versa. The photographic cutting in the documentation seems to clearly suggest a predominance of the human action over the landscape, a focus that is mainly dedicated to the human experience of the space.

[17] 'The first need to fix on paper the places is related to travel: it is the reminder of the sequence of steps, the route of a journey… The need to incorporate in one image the dimension of time together with that of the space is the origin of cartography… The map, even if static, presupposes a narrative idea, and is conceived in terms of a route. It is Odyssey' ('Il primo bisogno di fissare sulla carta i luoghi è legato al viaggio: è il promemoria di della successione delle tappe, il tracciato di un percorso. … La necessità di comprendere in un'immagine la dimensione del tempo assieme a quella dello spazio è all'origine della cartografia. … La carta geografica, insomma, anche se statica, presuppone un' idea narrativa, è concepita in funzione di un itinerario, è Odissea'). Italo Calvino, 'Il viandante nella mappa,' in Collezione di sabbia (Milan: Garzanti, 1984), pp. 23-24.

[18] This approach was anticipated by Dada at the beginning of the twentieth century: 'Dada does not intervene on the space by leaving an object or by taking samples, it leads the artist, better still, the group of artists, directly to the place to be revealed, not to do anything material, leaving no physical trace except for the documentation related to the operation ... and without any kind of subsequent processing'. ('Dada non interviene sul luogo lasciandovi un oggetto né prelevandone degli altri, porta l'artista, meglio ancora il gruppo di artisti, direttamente sul luogo da svelare, senza compiere alcuna operazione materiale, senza lasciare tracce fisiche se non la documentazione legata all'operazione … e senza alcun tipo di elaborazione successiva'. Francesco Careri, Walkscapes. Camminare come pratica estetica (Torino: Einaudi, 2006), p. 48.

[19] The second set of photographs was shot in 2003 by a team from the Sharjah International Biennial 6 (photographer Paul Thuysbaert), therefore representing a very different step and a substantial change in the process of documentation of his projects. Similarly Noor Al-Bastaki's work Paths and Steps (2005) shows a set context where an active audience has been gathered and parallels the artist in performing the action.

[20] The complete project Naked Sweet Potato, consisting of a book, 59 clay sculptures in seven metallic boxes, engravings on rocks, handmade jewellery, oil on canvas paintings, and a video, was presented at the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011 (Second time around, UAE National Pavilion, curated by Vasif Kortun).

[21] A work that presents some similarities, from the structural and formal point of view is Settlement – Six Israelis and One Palestinian (2010) by London-based Palestinian artist Steve Sabella.

[22] The photographs are taken by the same artist and no further public attends the shooting nor is involved in the documentation process, although for some projects in the past, Al Ghoussein has resorted to external assistance.

[23] Al-Shaikh follows and fully enacts the documentation process for instance in his video works My Land, 2, Not for sale (2004) and photographic projects. The participation of assistants is limited to few projects such as Trace, 1 (2009) and to very instructed phases. The artist thus remains the director of all the steps of the project. Omani Budoor Al Riyami's works present some tangencies with Anas Al-Shaikh's in the dramatic and powerful use of the body, where the action performed over it seems to be characterized by a ritualistic approach, to symbolize further dimensions and to breach into those. A different approach, in the sense of the level of physical involvement displayed by the artist and at some point requested of the viewers as well, appears in Wafaa Bilal's performances and interactive installations such as Domestic Tension (2007), …and Counting (2010), and 3rdi (2010).

[24] See also Amal Kenawy's You will be killed (2006), Layla Muraywid's Comme dans un jardin, j'attends le monde (2009), Cristiana de Marchi's Embodying (2010), and Fatima Mazmouz' Made in mode grossesse. La danse du ventre (2009).

[25] Joseph Tarrab, 'Le corps du délit', in in Le corps découvert, exhibition catalogue (Paris: Hazan and Institut du monde arabe, 2012), pp.37-47.

[26] I would like to quote an acute observation by Mohamed Rachdi about Moroccan painter Mahi Binebine, that seems to perfectly apply to Mohammed Al Mazrouei's pictorial practice: 'With this artist, it is unclear whether the bodies interlace or fight among themselves and with the material. In all cases, they intertwine, stretch, shrink, writhe ... like trying to sometimes fit into the limits of space, and sometimes to get out of them' ('Chez cet artiste, on ne sait pas vraiment si les corps s'enlecent ou se battent entre eux et avec la matière. Dans tous les cas, ils s'entremelent, s'allongent, se rétrécissent, se contorsionnent … comme cherchant tantot à s'inscire dans les limites de l'espace, tantot à en sortir.') Rachdi, op cit., p. 164. See: Mahi Binebine, Sans titre (2008).

[27] For example: Hassan Sharif, Mohammed Kazem, Abdullah Al Saadi.

[28] For example: Waheeda Malullah, Anas Al-Shaikh, Tarek Al-Ghoussein, Noor Al-Bastaki, Cristiana de Marchi, Ebtisam AbdulAziz, and Manal Al Dowayan.

[29] The end of the twentieth century is marked by the recourse to the representation of the body as an object of social martyrdom, a collective suffering that involves entire portions of a population, thus raising political issues through the representation of the body (Amal Kenawy, Azza Hachimi, Sami Mohamed, Sundus Abdul Hadi, Hani Zurob, Mahi Binebine, Tarik Essalhi, Azza Hachimi). In these artists (just like in AbidinTravel.com, the project in which Iraqi-Finnish artist Adel Abidin propose destroyed and tormented by war scenarios as touristic travel destinations, creating a situation of public involvement in which the body is absent and remains so until the entrance of the public itself, the body then becoming that of the viewer), art becomes a tool for raising and investigating current political issues, often addressed in an ironic way but where inevitably the presence of the body recalls and alludes to death or the denial of the physical bodily presence (See Le corps découvert, referenced above, 4).