Essays

Digital, Aesthetic, Ephemeral

The Shifting Narrative of Uprising

A brief look at image and narrative

With every new development of communication and information technology, the world changes slightly; and with every political movement, an aesthetic is re-formed. It is an oft-repeated adage that the Internet has altered the way we share information, communicate and see the world but the same was said about television and the invention of the printing press before that. These tools largely familiarized the world with the aesthetics that have become part of our everyday, visual landscape: think of revolutionary-cubism in 1920s Russia or the Kalashnikov-romance photography of 1960s Palestine.

In the last two years of uprisings across the Arab world, we have already seen a certain narrative emerge through images and texts, though it is still too premature to examine these fully. We have also noticed a cycle in the use and resonance of these images and the shifting of narratives. Amidst that, we have already seen a re-cycle of the raw material into fine art pieces making their way into commercial galleries in the UK, glamorising them and in a sense dislocating them from the mode in which they were created. By July 2011, in London alone, the three-week Shubbak festival was immediately problematized for that exact reason by attendees uttering their annoyance at the immediate cliché of an ongoing political crossover. The organizers' 'hasty reprogramming' to include the 'tumult of the Arab Spring'[1] was noted by critics.[2]

Still, the analysis of the images remains varied. The raw material and more 'produced' work stand at separate ends of the conversation. This friction is mostly in the disengagement between actual, momentary images of real-time action that are reused for means ranging from practice to the press. On the other side of the conversation are fine-art works that reframe this raw material into works that reflect on the moment they convey. This will manifest in various forms (film, theatre, visual art), will be either fiction or non-fiction, with audiences reacting subjectively to whether the piece is 'good' or 'bad'. These images feed a certain sort of 'simulation' of the reality they reflect by masking them with displacement, either in the interpretation of the event or in the setting in which the works are presented. This friction between the two is comparable to Roland Barthes' negotiation between the 'punctum', or emotional involvement of the viewer with an image, and the 'studium', images that carry a more symbolic meaning.

In this era of image-heavy uprisings in the Middle East, one can look at the shifting use of imagery just as much as its content. Tracing the purpose of the now emblematic on-the-run, hazy imagery to its appropriation into fine art commodity shows a shift in narrative of the so-called 'Arab Spring'. Some may argue that this has de-legitimized or watered down the purpose of political imagery and the creation of political art, feeding into notions outlined in Guy Debord's The Society of the Spectacle (1967). In Debord's conception, society turns experience into representation, diminishes spatial realities and the distance between the past and the present. In Debord's society, people are automated by the image, fooled by it: image rules familiarity. Others may go even further and argue that this preoccupation with the image and the uprisings came at the price of imagining a real revolution. The question that this poses is whether this is a crisis in art, or a crisis in politics. But as we will see in the works examined, the power of looking has separated the image from the actual will to act, despite the active resonance of these images.

The 'Arab Spring' narrative

At times it is almost as if intellectual and cultural status-quo is more affected by political revolutions than government systems. Mainstream news articulated the narrative of unity, broken fears and fallen governments to various ends. News sources, like The New York Times for example, one of the champions of the term 'Arab Spring', referred to this as an 'awakening' of the Arab youth, gave endless credit to the Internet, namely social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter, and satellite television for exposing them to liberal societies and 'fueling the anger at repressive governments',[3] framing the user of the Internet as passive. The aesthetic of hand-held, grainy, on-the-run footage, with shirtless men on the ground, usually accompanied by the sounds of people shouting slogans calling for the fall of the regime, gunshots and takbeers,[4] all relay the fleetingness, bravery, self-determination and euphoria of that time. This became a mainstay, in turn fueling ideas by the likes of The New York Times that social, mobile new media unlocked the Arab slumber.

Simultaneously though, this narrative of euphoria overshadowed the reality of the betrayal, brutality and deaths that also occurred. At times, it was almost as if the euphoria that came about through one man's stepping down, and the need to preserve that moment through image or otherwise, clouded what was to come. This brings to mind a comment made by American video artist Dara Birnbaum about the difference between that 'Utopian moment and the reality of the here and now', turning these images into reveries rather than memories.[5]

Aesthetically, movements' visual codes and the arts will merge at some point. The inherently inspirational tone of an uprising by definition calls for voices and expression.

Active archives, media unbound

In a variation of Gil Scott-Heron's echoing phrase, rather than the passive, televised revolution of his time, the 2011 uprisings were digitized. It was hash-tagged, uploaded, and remained free of copyright, so anyone with access could spread, join, and add to the 'billions of billions of characters' that will remain in our virtual memory forever.[6] We are in a state of active sharing of information and memory-building.

In his 1974 essay The Technology and the Society, the late Raymond Williams came up with a list of assumptions pertaining to television as an invention resulting from 'scientific and technical research':[7] It altered the movement of information and entertainment, social relationships and basic perceptions of reality. He goes on to say that it was an effect of greater global mobility, another result of technological advancements and the way in which we associate with the size of the world, now seen as 'shrinking'. In terms of lasting effects, these exact conditions developed the way new media (the Internet, social networks and the fast-changing use of digital information in the form of text, image, video, and so on) and entertainment operate and lead to new ways of forming opinion. Williams considered that technology may be an accidental advancement, but one that answered to human nature and a human need. Digital media has ignited the latent need to be actively involved, to be authors, for people to tell their own stories. In terms of communal involvement, digital media has introduced concepts of crowd sharing and collective development of information in creating and sharing information alike.

The archive of ephemeral, lo-fi, endless information created in the last 18 months is a scattered one that was created instantly and urgently with hand-held devices, proscribing the possibility of an archivist to maintain this information. They were uploaded on the spot into our current information systems, networked throughout the globe: this propensity was elastic, dialogic, and eventually became emblematic. The danger lies in thinking that credit must go to the tools (Internet) for allowing the movement; it is a patronising misrepresentation of an active, willed movement that used media to narrate a people's agency. The youth used these tools to disseminate information and images in ways that reflected their need and fed into a cycle of empowerment of the independent voice, redistributed as a consistent reminder and self-reflection of an ongoing movement.

Retroactive Reflection through the Arts

As a reflection of the movement it was trailing, this inadvertent practice, for better or worse, paralleled it: fast, fleeting and un-centralized. It challenged ideas of power, control, knowledge and memory. With the current trend for focusing on personal, social, and political memory and the archive by artists such as Rabih Mroué, Akram Zaatari, Ala Younis and quite a few others, it is no surprise that when the unprecedented historical event rose into chaos, artists reacted by working these current political documents into their work. Artists in the Middle East have been retroactively reacting to historical events by way of whatever media they can amass, memories people have of the events and using their imagination as an attempt to complete, and maybe dislocate themselves from, the story. The group of Lebanese artists who are still grappling with Civil War, for example, years after its end, deal with its psychological, social and political remnants. The work of Walid Raad and the Atlas Group seeks out, preserves, and categorizes any bit of media that can allow for a tracing of individual and communal (hi)stories of the time. In their press release for Rabih Mroué's exhibition I, the Undersigned in the Netherlands in 2010, BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, questioned his position in bringing up the age-old friction between an artist's aesthetical framework and his responsibility to react to political currencies.[8]

Meanwhile, Akram Zaatari's exhaustive work on the image and self-image through photography in the Middle East is a case in itself. While developing the Arab Image Foundation (AIF), he also produces his own artworks that at times ask similar questions as those presented through the AIF, while engaging with questions of new media and marginalized and (thus) imagined (self-)identities. His recent 25-minute work Dance to the End of Love looks at lo-fi, most likely mobile phone-produced, You Tube-d self-portrait videos by young men around the Middle East. His four-channel film mines videos of musicians, body builders, and notoriously daredevil Saudi truck drivers. These videos showcase an opportunity to perform and self-illustrate; they are imaginative, aspirational and daring, even if only in play, pointing at the youth's psyche and the need to carry out a certain sense of self-realization. Here we see young men taking hold of their own dreams and making them public, even if from within the private realm.

Similar aspirations can be seen in the way North African and Middle Eastern youths have been expressing themselves on the streets, and subsequently You Tube, since 2011. Now, rather than being trapped by the retro-pensive burden of memories, youth movements seized the current, in tools and the zeitgeist, and in the meantime nullifying the dominant voices of corporate and government media, and the propaganda of the day.

An archive that is in use while it is being produced becomes both historical documentation and resistance material. The images and stories within this greater archive make it active and dynamic. It is not unique to today, for we have seen in the past networks of resistance filmmakers and documentarians who had even stronger practices working to a similar idea. Today, while there is perhaps no iconic image for the movement, it was the act of taking pictures with mobile phones that became itself iconic. The character of Farah in Ibrahim El Batout's 2011 film Winter of Discontent directly embodies this. As soon as she quits the state-run television programme working to quell the voice of the ongoing protests in Tahrir Square, she joins activists on a building rooftop with her own handy-cam in hand. The work of Mosireen took this to another level. They not only make sure that there is documentation of ongoing brutality, but also footage to be used by third parties and training in order for more people to create more video documents.

The merging of this hand-held, on-the-run aesthetic with cinema, theatre and fine art experiments with the use of media, expresses multiple dimensions of reality and emotions, while also addressing the unknown. The attempt to negotiate the ongoing frenzy came in the reframing of the same images of these grainy realities showing people on the ground, images that carried the heightened senses, the rough sounds, the empowerment (yet still) and the violence of the moment.

On (self-)reflection: a narrative in pictures, shifting

The friction between the raw image and its use in produced, creative work, is part of an ongoing saga of its own. While empowerment remains in these now recognisable lo-fi images, they are also moving towards an escapism of their own.

One short film, available on Vimeo, is Conte de Printemps by Syrian collective Le Chaise Renversee. This five-minute film, made to honour the protestors of the Syrian uprising, uses You Tube-style videos and sounds of the most emotively recognized type: gunshots and takbeers, shirtless men with their arms in the air and bloodied hands vowing victory. Interlaid with an animation of paper figures being stepped on, it plays what look like mobile phone videos of youths running on the ground. But as these rough images play on, we slowly see the paper figures rise again. We have seen the youths on the streets, their hope and courage, and we have seen the paper people rise back up.

The empowerment of reviewing and reassessing one's self-image was illustrated well by Malu Halasa during the presentation of her essay 'Alternative Histories: Middle Eastern Portraiture, Photography, Art, Documentary, Illustration and Fashion Today, an Illustrated Lecture on Contemporary Visual Culture of the Middle East'at the National Portrait Gallery in December, 2011. The essay reflects on imagery in North Africa and the Middle East since the uprisings earlier that year. Most profoundly, she discusses a conversation she had with Egyptian photographer Yasser Alwan, who has been taking street portraits since the 1990s. Halasa writes that Alwan noted that his portraits made people 'recoil and react unpleasantly', caused by their shame at 'being Egyptian'. But after the 25th of January 2011, this sentiment and self-image changed; now there was a feeling and image of perseverance among the working class of Cairo, a post-revolutionary pride. In her presentation, Halasa shared a video clip[9] that shows these portraits, overlaid by iconic speeches about pan-Arab empowerment by Gamal Abdel Nasser and a song from the 1960s called 'Sura', meaning 'image', that epitomized the feeling of unity and inclusivity at the time; this song, the narrator of the clip says, became the anthem of the 2011 Egyptian revolution. While these thoughts came in retrospect regarding previous works, they embodied the euphoria and pride that can now be looked back at as lost. The narrator of the You Tube clip then goes on to tell the immaterialized fate of the great intention of the pan-Arab ambition.

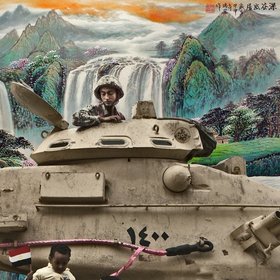

As if in a cycle, similar to the cracked self-image of the Egyptian society referred to by Alwan, the narrative of the so-called 'Arab Spring' eventually started to shift. Contradictions arose between fear and courage; hope and despair; victory and self-reflection and self-criticality. We see this illustrated in the impressionist-meets-realist exploratory photography of Nermine Hammam. Having created two series of images in reaction to the 18-day Egyptian uprising, we see that narrative shift in the consecutive images depicting mixed emotions. Her first series, Uppekha (2011) puts together photographs she took of the army in Tahrir Square; she manipulates these photos by tweaking the innocence in the features of the young, male soldiers by hand-painting them and replacing their backgrounds with images of Swiss mountain landscapes and Japanese cherry-blossom vistas. Her scepticism comes full-blown through her second series Unfolding (2011), for which she uses images of aggressive protest scenes from the press, some of them now infamous. Among them are images of the 'Battle of the Camels' and the attack on the 'girl with the blue bra', images taken by civilians and then used by mainstream press. These are more detailed scenes, again, placed against a backdrop of Chinese silk-screens and other beautiful patterns.

Hammam though insists that she was not documenting the experience, but rather negotiating a fleeting moment that will not end the way it began. I ascertain, however, that this artistic rendition of what she describes as maternal protectiveness ('I wanted to just get these boys out of there', she said[10]) and a precarious moment, still stand as documents that represent the moment in which she created it. Unfolding is an example of work that not only reflects that moment, but utilizes raw material meant to spread information about the movement, and then finally endw up in the displaced setting of a west London art space (in this case, the Mosaic Rooms). In her artist's statement for this series, Hammam notes the disconnect between reality, image and art. 'When [they] die on camera, their death is distorted in an endless loop of info-tainment … Images on repeat build up our emotional immunity, a shell that threatens to cut us off from our humanity, our capacity for empathy', she says. She goes on to express the distance that the screen presents and the irony it entails and asserts that these works served to 'mock the artistic industry forming around the revolution', referring to the relationship between the viewer and artwork as a 'sado-masochistic' one.[11] The works themselves have now entered the photography collection of a major British institution, the Victoria and Albert Museum.

A piece that looked at the post-euphoric stage of the uprisings by experimental means is the Tunisian rendition of Macbeth by the production group Artistes Producteurs Associés (APA), re-subtitled Leila and Ben: A Bloody History. While this play uses digital means to convey their exploration of the cycle of tyranny in Tunisia, the producers of APA made a conscious decision to stay away from the You Tube-style imagery and sound to create their own. They found the hand-held aesthetic to be too 'obvious' and decided to keep it abstract. Deciding to dramatize a Shakespeare play in a way that had clear and bold resonance with recent history, they stood apart from other works reflecting on this historical chapter clumsily referred to as the 'Arab Spring'. They chose to create their own aesthetic of political malice: dramatic caricatures of Leila and Ben Ali as characters in the play; music of various kinds to instill the mood of power, submission and fear; images of rabid dogs to communicate tyranny, and snippets from documentaries and interviews to reflect on the social and political trajectory of the country. Having been received by some reviewers as 'hard work'[12] and too far from the original Macbeth, it is a wonder if the lack of understood, coded and aesthetic symbols of the ongoing uprisings made it difficult for people to know what the play was about.

By way of these decisions, the play set itself apart from works that can be considered among the canon of 'Arab Spring' art and rather presented a more thoughtful, socially reflective and culturally critical look at the Tunisian (and the greater region's) complacency and passivity in the area of politics. Ironically, this aestheticized musical performance stood outside the spectacle of the 'Arab Spring'.

Over aestheticising:

Familiarity of the mood and style of the images that inadvertently came to signify this chapter of the ongoing struggle have lead to a certain seductiveness; they are familiar, suggestive of an insider's eye, a sort of hyper-reality that draws people in, representative of what is seen from a distance and happening in real time. As was have seen in the banal reaction to APA's re-tooled Macbeth, stepping away from certain codes of recognition loses track of the moment being reflected on.

Images constituting the narrative of political upheaval have gone through a process of moving from the Barthes-ian 'punctum', and bypassed his 'studium' towards a Baudrillardian simulacrum - a state in which people have a stronger relationship with the image and symbol than the reality, once again, a spectacle that society has come to gaze at. Images that started out as raw documents showing brutalities and self-determination held their emotional connection with the viewer. They informed, they were current and they were urgent. From there, they moved on to being parts of stories created by artists replicating and negotiating realities with the help of such 'real' images, creating works that led to realities being superseded by their own image. The same grainy footage of the young man with bloodied hands seen in the Syrian short film Conte de Printemps also featured in El Batout's Winter of Discontent.

In this act of looking, people have became accustomed to the mediated, and now aestheticized, images of highly emotive events, overtaking the reality of the political process in flux. The images romanticized the proletariat's voice in Tunisia, the 18 days in Egypt, days that seemed to slip through the fingers of the youths who propelled the movement. At times, being vocal and documenting the situation became more prominent than the end goal, all the while feeding the spectacle. Those days of hope and euphoria quickly became overrun by the fear, tension and brutality that hovered throughout.

In his Future of the Image (2007) Jacques Rancière points out the disconnection between the simulation created by the apparent 'truth' in imagery and political arts. While I consider that negotiating this frenzy in an artistic way is necessary, the eventual romanticization signifies its own passive development. The spectacle has developed, while the political movement, ongoing and incomplete, has become desensitized to the value of its original purpose.

[1] Maev Kennedy, 'Arab Arts Festival to Debut in London,' The Guardian, 26 May 2011 http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/may/26/arab-arts-festival-debut-london

[2] This creates another issue: the grave difference between the art seen locally in the cities where these uprisings took place, and that which travels to western galleries and institutions. This essay will develop with that blind spot in mind.

[3] Michael Slackman, 'Bullets Stall Youthful Push for Arab Spring,' New York Times, 17 March 2011 http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/18/world/middleeast/18youth.html?pagewanted=all.

[5] Dara Birnbaum, 'Reverie: As an Illusion of Memory,' conference paper, Memory Marathon Conference, Serpentine Gallery's Memory Marathon, London, 14 October 2012.

[6] Viktor Mayer-Schonberger, Delete: The Virtue of Forgetting in a Digital Age (Cambridge: Princeton University Press, 2011).

[8] Rabih Mroue, 'I, the Undersigned,' E-Flux website, 1 March 2013 http://www.e-flux.com/announcements/rabih-mroue-i-the-undersigned/.