Essays

Thieves of Babylon

Repatriation of Iraq's Looted Heritage under International and Domestic Law and Practice

During wartime, art and culture are among the first to suffer but among the last to receive attention. Protecting museums and cultural sites in the wake of bloodshed and destruction is understandably not the highest priority on anyone's agenda. Since the extensive Holocaust lootings that happened after World War Two, a growing body of legal and customary obligations between the art-rich, so-called 'source nations', and the art-poor 'market nations' obliges occupying states to safeguard such heritage during wartime. The most important amongst these is the Hague Convention, which was brought into being in order to protect, and prevent the damage and destruction of, cultural heritage in situations of actual or potential armed conflict, through a process of mutual implementation. Under this, signatory states are responsible for devising lists of important objects and disaster plans, and using the 'Blue Shield' to mark out items of significant cultural importance (akin to the Red Cross symbol of the Geneva Conventions). It is further described below. Some important treaties, the UNESCO Convention of 1970 being the most significant, also now require signatory states to return antiquities found on their soil and discovered to have been looted to the territories that rightfully lay a claim to them.

This essay continues the well-debated topic of Iraq's looted heritage following the 2003 US-led, UK-aided overthrow of Saddam Hussein, from the perspective of the international and national legal regimes that enable the repatriation of such heritage. The focus will be on claims in the USA and UK, where looted items are most likely to have been transported (70,000 artefacts are currently believed to be in the USA). In Iraq's case, I aim to ask: how realistic is repatriation? Moreover, is repatriation even desirable, if the political circumstances in Iraq continue to render the satisfactory preservation of the artefacts too uncertain to risk their return?

Part One. Iraq

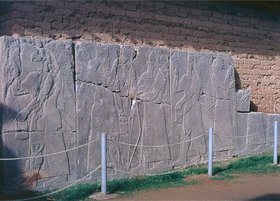

The case of Iraq takes on acute global significance because it is located in a region of historical relevance. Observers have strongly criticized the occupying forces' failure, post-2003, to safeguard treasures of not just national but international cultural significance. These include the 'Warka Vase', the Akkadian copper statute from Bassetki, and the bird sculptures from Nemrik, amongst many others. UNESCO's First Mission to Iraq reported that out of the 10,000 items said to have disappeared during the period of conflict, only 650 or so were recovered, and many of them were forgeries and fakes. The National Museum of Baghdad was reported to have lost at least 40 of its most precious items. The Museum inventories (card catalogues and computer files) were destroyed, and it is reported that almost the entire collection of 12 million volumes at the National Library and Archives were burned.[1]

By comparison, considerable efforts were exerted to protect the Ministry of Interior, which held intelligence records on petroleum resources and oil fields, the seizure of which was an objective of the occupying forces.

John Russell, a specialist in Mesopotamia, was the Deputy Adviser to the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) and Senior Adviser to the Iraqi Ministry of Culture between 20 September 2003 and 20 June 2004. He is currently advising the US State Department on the repatriation of items of Iraqi heritage looted after the invasion. Russell says westerners should care about Iraq's lost heritage, even though they may not understand at first how their histories are directly related. 'The ideas of city, citizen, civic duty, civic architecture, civilization all arose first in Iraq',[2] he writes. 'It is the people of the past who civilize us. If we don't acknowledge them as our ancestors, then God help us.'[3]

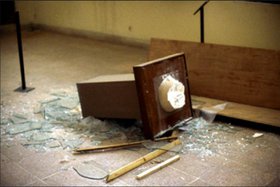

As a barrister practising in the UK, Zia Akhtar believes that 'the plundering of the Iraqi National Museum was the most publicly visible manifestation of the relinquishment of protection that was the US forces' duty in occupied Iraq.'[4] Indeed, the Museum was not just a place to display artefacts but a central hub for collecting the archaeological findings of international excavations. It possessed a database of knowledge that was accessible to international researchers. The destruction of this database and the looting of its contents represented 'a reversal of not just national but world scholarship, and threatens to turn the clock back 150 years.'[5]

International treaties require that source nations also take responsibility for safeguarding their own heritage, at least during peacetime. Between 1991 and 1994, during the Gulf War, 11 regional museums in Iraq were looted, resulting in the theft of 3,000 artefacts and 484 manuscripts, and culminating in widespread illegal digging across the land in 1995. Only around ten per cent of the items are believed to have been recovered. After this experience, the Iraqi government took steps to protect the country's art collections. Measures were put in place to secure museums in anticipation of the invasion in 2003, such as moving items to underground locations, insulating the National Museum of Baghdad with shock-resistant material, and placing distinctive signage on the roofs of cultural institutions to deter their bombing. However, many of the heavier items could not be moved, and in the chaos that immediately ensued the fall of the regime, including the collapse of the Central Authority, many museum staff had to flee for their lives, leaving whole rooms and wings filled with unguarded artefacts. Among the items protected from destruction were the so-called 'Treasure of Nimrud' and other important treasures.[6] However, in total, it is believed that over 15,000 items were looted, comprising 40 or so major items on display, as well as thousands kept within the museum's stronghold and archives. These do not signify the exact figures but the nearest estimate taken shortly after the invasion.[7] Some significant pieces were recovered and restored within eighteen months of the invasion, including the famous 'Lady of Warka', the sculpted marble head of a woman, dating from about 3000BC, and the 'Bassetki Statue', dating from about 2200BC. The Warka Vase, an alabaster vase decorated with elaborate relief scenes dating from about 3000BC, though returned voluntarily, was broken into numerous pieces.[8]

Eyewitnesses also claimed to have seen western soldiers actually directing and ordering civilians to conduct parts of the looting. It was an operation that, in hindsight, appeared to have been carefully and intelligently planned and executed.[9] In a British newspaper article published in 2003, McGuire Gibson, president of the American Association for Research in Baghdad, states: 'the vaults where the best pieces are kept were opened with keys. Looters coming in off the streets don't usually have keys, do they?'[10] There is also anecdotal evidence that foreign art dealers had 'shopping lists' of precious items, which they had reason to believe would be looted during the invasion, and that they were conducting transactions for these before the overthrow of Saddam, and sealed those transactions shortly after the raids had happened. 'We already have reports of exhibits being offered for sale in Switzerland and Japan,' Karl-Heinz Kind, Interpol's specialist officer for art and antiquity trafficking, said, in the newspaper article mentioned above. 'Even in a war zone, even with the country practically sealed off, these things can move with incredible speed.'[11] To make matters worse, at the time of the looting, the US government had not ratified the UNESCO Convention of 1970.[12] This also impacts on bringing the US government to account for its army's failure to protect Iraqi heritage during the conflict.

Part Two. The 'Transnational versus National' debate

These issues are not novel. However, practically speaking, what can be done? For Konstantin Parkhomenko, a solicitor practising in the USA, the debate on how, and to what extent, acts of illegal exportation should be deterred by acquiring nations takes on what he calls 'a national versus a transnational' dimension. Parkhomenko argues that 'in order to take our culture seriously we must protect it on the global, rather than national, scale, [as] focusing only on national interests does not make sense in the regulation of the antiquities market [where] the interests implicated are not those of any single nation, but rather those of humanity as a whole.'[13] This is the 'transnational' approach. The claim is that international institutions in the developed world are better placed to make such items available to a wider audience – an audience that would otherwise be deprived of them were they to be returned to their homeland. However, the strength of the 'nationalist' approach resides in the argument that culture is environment-sensitive, and that an object ripped from its surroundings (such as a great relic taken from the pyramids of Giza) loses its contextual significance.

Both are valid arguments, and, as Parkhomenko says, make disputes in repatriation claims challenging to resolve because 'both the current possessor and the nation of origin claim a seemingly legitimate interest in the artefacts in question.'[14] The resistance that will be encountered in repatriation actions is likely to rise with the cultural value of the items in question. The UK government, for example, believes it has a stronger claim to the Rosetta Stone and the Parthenon Marbles (currently housed at the British Museum) although Egypt and Greece would disagree. Items such as jewellery or coins bearing Saddam's image, or his ceremonial sword, on the other hand, have been returned voluntarily with much flourish, because they are not of equal significance.[15]

It is a different matter where the context itself has been damaged, as in the cases of Iraq and Syria. Arguably, it is unsafe to return precious items to ravaged and unsafe states unable to take care of them.[16] And yet, for Russell, He writes:

…the story [of Iraq] resides not in the object but in the haze: the houses, temples, palaces, graves, farms, towns and cities in which these objects functioned. If that context is carelessly destroyed, as when a site is plundered for the antiquities market, everything about the object from its geographic location to its immediate surroundings is lost. What survive are only mute fragments of a story now lost forever.[17]

To address the problem of bias, Parkhomenko advocates the establishment of an independent international court, whose jurisdiction is tailored towards resolving cultural property issues. An examination of such a proposal is outside the scope of this essay. However, as long as consensus on the application of the international treaties cannot be reached, the current author believes that the proposal is ambitious, especially given the prevailing imbalance between 'market' and 'source' nations. The funding of such an institution is likely to come from the 'market nations', meaning that it is likely to serve the interests of those nations rather than the poorer, art-rich states.

Part Three. The international legal framework

Since the 1950s, a framework of international multi and bilateral treaties has emerged and developed to

tackle the problem of destruction and looting of cultural heritage. However, international treaties are only as effective as the states that apply them. In the absence of an international court, the domestic statutes that interpret the laws, and the courts that enforce them, become paramount. But the political landscape is changing. With some recent successful examples of recovery and prosecution, the prospect of repatriation is not unattainable. However, this also depends heavily on the attitudes of the claimant nations.

A. The Hague Convention of 1954

The first major convention to consider the illegal destruction and looting of cultural property was the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (the 'Hague Convention'). This represented the first step in the international journey, and was borne of an urgent need felt by the global community, following the unprecedented destruction and looting of cultural heritage in the Second World War, to recover and protect such heritage.

To start with, the term 'cultural property' is not universally defined. The Hague Convention merely states that the term includes property of 'cultural importance'. Further, each nation is free to interpret the term as it sees fit. This may cause interpretational hurdles for countries such as Italy that have strict views on what cultural property comprises, and that wish to bring a claim in foreign jurisdictions that assess the term differently. The UNESCO Convention of 1970 defines cultural property more comprehensively as that which 'on religious or secular grounds is specifically designated by each State as being of importance for archaeology, prehistory, history, literature, art or science.'[18]

Although the Hague Convention was signed by over 120 states, including the USA and the UK, an international treaty only has practical force in a signatory state when it is ratified. Having played a part in drafting the text, it took the USA over 50 years to eventually ratify it in 2009. The UK has still not ratified the treaty, which impacts negatively on its aspirations to be a global leader in the international humanitarian sphere.[19]

The Hague Convention is nevertheless important because it imposes positive obligations on occupying forces to safeguard cultural property when occupying all, or part, of a foreign state's territory, and requires all such property to be returned to the state's competent authorities upon termination of hostilities. It relies on diplomatic channels of enforcement, such as the 'blue shield', which can be displayed on flags or armaments in order to protect sites from destruction during wartime.

B. The UNESCO Convention of 1970

The second major (and currently leading) convention to be enacted was UNESCO's Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property of 1970 (the 'UNESCO Convention'). The UK and the USA number among the few 'market nations' to have ratified the UNESCO Convention.

As the first treaty to recognize the rights of third party states to request the return of their cultural property, the UNESCO Convention provides that the import, export or transfer of cultural property effected contrary to the provisions adopted under the Convention by the signatory states 'shall be illicit.'[20] However, it is subject to limitations. According to Andrew Adler, technically speaking only the 'export' of cultural property is practically caught by the prohibition. Although 'imports' are defined as 'illicit', the UNESCO Convention is silent as to the punitive effect of illicit imports.[21] Legal capacity is arguably a bigger hurdle; only state parties are entitled to invoke the UNESCO Convention. This is problematic where one depends on the government of a 'source' nation that may not be able to dedicate enough time and resources, nor have adequately trained staff, to meet this mission.

Another major obstacle is that the objects need to be designated on a list, so one cannot rely on the UNESCO Convention with respect to items that may have been excavated anonymously at an unknown time, and that are not independently recorded. The Iraqis may have no way of demonstrating ownership of looted items that were, for instance, either unlisted, or that existed in records that have since been destroyed.

Moreover, the UNESCO Convention does not apply retrospectively, which means claims cannot be backdated to artefacts looted before the date of a state's accession. Finally, it does not create a direct obligation on signatory states. Rather, their responsibilities are defined in accordance with the bilateral or multilateral treaties they may enter into under the treaty, or their domestic implementing law. This leads to discrepancies between the signatories' respective application regimes. In the case of the USA, the treaty is entrenched in the Cultural Property Implementation Act 1983 (the CPIA). The USA has also entered into 14 bilateral agreements with third party states under the UNESCO Convention. These include an accord with Iraq, under which the USA promises to repatriate archaeological or ethnological material pillaged from Iraq. The UNESCO Convention may also be incorporated through ethical guidelines, such as those of museums.[22] This reflects Patrick O'Keefe's observation that the UNESCO Convention's force has ultimately derived not from its implementation, but from its transformative 'maturation of public attitudes.'[23]

C. The UNIDROIT Convention of 1995

A third treaty, the UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects of 1995 (the 'UNIDROIT' Convention), is also worth mentioning here. It may seem a more effective route for the recovery of illegally exported artefacts because it allows claims to be brought through private legal channels as well as diplomatic channels (unlike the UNESCO Convention). However, many relevant 'market nations' such as the UK and the USA have not endorsed the UNIDROIT Convention. It shall not therefore be considered further here, but is useful to take into account for repatriation claims against other states, barring the USA and the UK.

Part Four. The domestic legal framework

International conventions do not operate within a vacuum. As mentioned above, they are only as effective as the states that implement and exploit them under their national laws.

A. The United States

In addition to the bilateral treaties that the USA has entered into under the UNESCO Convention, it has implemented the treaty in the CPIA.[24]

However, the CPIA has some important caveats, including what Akhtar calls the 'self-justifying exception'. Essentially, this allows the USA to refuse repatriation where it believes the claimant nation is incapable of looking after the antiquities on its territory. The ongoing insurrection in Baghdad does not, then, work in favour of the National Museum of Iraq.[25] Professor John Merryman of Stanford Law School goes as far as to say that stolen objects may even be lawfully imported into the USA in situations where their market value is enhanced: 'in an open, legitimate trade, cultural objects can move to people and institutions that value them most and are therefore more likely to care for them.'[26]

Parkhomenko appears to agree, but considers the 'economic value exchange' to be a balanced matter between the provider and the acquirer. He has stated that 'art has the potential to generate large amounts of value both for the art-rich "source nations" as well as for the "market nations" where the artefacts end up.'[27] Just how stolen artefacts may generate value for a nation that is deprived of them is debatable. Although a satisfactory answer is not provided, it is this author's view that custodianship possibilities may provide a temporary solution.[28]

Where international treaties lack punitive bite, US criminal legislation, in the form of the National Stolen Property Act (NSPA), can prove quite effective for the claimant state, with or without the support of a bilateral treaty. Assuming a foreign state proves ownership, unlike the CPIA, the NSPA provides heavy criminal penalties for the perpetrator.[29] In the 2003 case of United States v Schultz,[30] a prominent art dealer, Schultz, was convicted under the NSPA of conspiracy to receive stolen Egyptian antiquities. The Egyptian government was successful in proving ownership of the items through one of its domestic laws, which declared that all antiquities found in Egypt after 1983 were the property of the state. To combat the evidential hurdle of proving ownership under state civil and criminal laws, Iraq could take a leaf out of Egypt's book and pass a law holding all antiquities found on Iraqi soil after, for instance, the Gulf War, to be property of the Iraqi government. This would enable actions to be brought where such items are taken outside its borders, assuming the other conditions to bringing a claim are met.

Needless to say, those operating in the international art market must always remain vigilant to opportunists who exploit the fact that the art and antiquities market remains unregulated and wide-open to abuse, with major 'institutions [which] continue to hold out one hand while covering their eyes with another.'[31][xxxi] These include Cornell University, which accepted a gift from well-known collector Jonathan Rosen in 2000 of cuneiform tablets from Ur (Iraq) without investigating their provenance, despite reports of widespread looting in Ur after the Gulf War of 1990, and despite the fact that a sizeable portion of the treasure was labelled as emanating from 'uncertain sites'.

More worrying still is that ten years after the looting of the National Museum of Iraq, which saw anecdotal evidence that the sale of antiquities was funding the insurgency, similar reports emerged of the sale of antiquities in Syria to fund fighting.[32] Evidently, lessons are not being learned.

B. The United Kingdom

The UK, unlike the USA, did not enact specific implementing legislation for the UNESCO Convention. However, its domestic civil and criminal laws enable repatriation claims. A landmark case in 2007 in the UK proved that under civil law, states could successfully bring reclamation actions. In December 2007, following an appeal to an earlier court case, the Iranian government secured the right of ownership for eight artefacts believed to have been excavated illegally from the Jiroft region, which had been on sale at a Mayfair gallery in London. The case established that foreign states could bring claims based on property rights in the British courts. Yet it still took Iran five years and millions of pounds in fees to establish their right. To date, the items have not been returned.

Statutory legislation exists in the UK in relation to Iraq via the Iraq Sanctions Order of 1993 (the ISO). This is a widely defined act dealing with the removal of protected cultural property from Iraq after 1990. It has the power to impose criminal sanctions and imprisonment terms, placing an obligation on the possessors of unlawfully gained artefacts from Iraq to give them up to the UK police, with a view to returning them to Iraq. Under this statute, a high burden of proof is placed on the defendant to show that they were not aware they were in possession of unlawfully removed property. To this author's knowledge, no prosecutions have occurred to date under the ISO, but some commentators believe it has acted as deterrent, especially to auction houses and art dealers.

Non-binding museum guidelines in the UK also play an important role. The Museums Association (MA)'s Code of Ethics is taken seriously amongst its 600 institutional members and over 5,000 individual members. In the MA's Code of Ethics there is an obligation on MA members to 'deal sensitively and promptly with requests for repatriation,' and in so doing, to take into account a multitude of factors ranging from the law to the educational and historical importance of the items, and their future treatment.'[33]

The MA Code unofficially implements the UNESCO Convention, and backdates its application to 1970, when it was signed. Museum guidelines in the USA are less stringent, however. The Metropolitan Museum of Art's practice, for instance, is to check provenance documentation for objects only for the ten years prior to acquisition. This means that the Met, as of this year, may turn a blind eye to the provenance of objects that might well have been looted from Iraq in or before 2003.

Part Five. Private law considerations and the claimant's role

Fundamental private laws play a large part in the practical enforcement of theoretical ideals.

First, the state must prove ownership to the thing claimed. Second, even if the evidential barrier is overcome, a claimant must show that its rights over property prevail over a person who purchased it in good faith. In certain jurisdictions, an item cannot be reclaimed by the original owner from an innocent purchaser who bought the item in good faith (such as in the UK, after six years have passed since the property's acquisition).

Where both ownership and title to sue are undisputed, problems may still arise where the source nation is unwilling to go through the practical steps to make a valid repatriation request, because the effort is not at the forefront of the government's agenda. Education of government and museum staff in Iraq on how to enforce these repatriation rights under the law is also vital; how can one expect a sword to be used with efficacy without proper instruction? It is, however, a step in the right direction that an agreement has been struck between senior government officials in Baghdad and the USA to repatriate more than 10,000 items found in the USA after the 2003 invasion. If these promises translate into a physical return of the items in question, it augurs well for future repatriation claims.[34]

Conclusion

There is no question that the looting and destruction of the National Museum of Iraq amounts to one of the greatest international cultural catastrophes of our time. The subject has even attracted the attention of prominent Iraqi artists such as Hanaa Malallah, who has made the theme a subject of her artwork.[35] Although international and national laws are in theory at the Iraqi state's disposal, the reality is that once art crosses borders, the task of repatriating lost items is much harder. In the absence of a centralized repository of information, hurdles arise in proving ownership as a first step. As a second step, factual aspects such as the original site of the looting, and proof of each step of the transfer chain, should be shown.

Ultimately, 'market nations' remain unwilling to return to 'source nations' artefacts of global cultural significance. So while both the transnational and the national approach have their merits, the current author proposes that there may be a 'third way' to deal with the issue in Iraq. These include so-called 'ethical solutions.'[36] One such solution is to engage in long-term loans, whereby it is agreed between the source state and the acquirer that the latter looks after the property temporarily (for instance in a museum). Custodianship is another option, whereby the Iraqi government agrees that an international 'neutral' institution become a 'trustee' of looted property.

However, even these 'ethical solutions' depend on states coming to a political agreement that Iraq is the rightful owner of the artefacts in dispute. In the end, debate proves to be somewhat academic. As Matthew Bogdanos, the US Marine Corps Reserves colonel who led the US investigation into the looting of the National Museum of Iraq in 2003, concludes, 'the sine qua non of effective interdiction is an organized, systemized, and seamlessly collaborative effort by the entire international community.'[37] Rebuilding the Hanging Gardens of Babylon may be an easier task...

[1] John M. Russell, 'Why Should We Care?' Art Journal 62.4 (Winter 2003): 22-29.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 22.

[4] Zia Akhtar, 'Theft in Babylon: Repatriation and International Law,' Art Antiquity and Law 17.4 (December 2012): 344-345.

[5] Ibid., 345.

[6] Dating from 860 to 700BC. Also protected were gold finds from the Royal Tombs of Ur, dating from about 2600 to 2400BC, and a life-size head of an Akkadian king, cast in copper and found at Nineveh, which dates to ca. 2200BC.

[7] See 'Oriental Institute Continues to Support Search for Missing Iraqi Artifacts a Year after Looting,' University of Chicago News Office, 8 April 2004 http://www-news.uchicago.edu/releases/04/040408.looting.shtml.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., 329.

[10] William Langley, 'Raiders of the Lost Art,' The Telegraph, 20 April 2003 http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/iraq/1428020/Raiders-of-the-lost-art.html.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Discussed below.

[13] Konstantin Parkhomenko, 'Taking Transnational Cultural Heritage Seriously: Towards A Global System For Resolving Disputes Over Stolen and Illegally-Exported Art,' Art Antiquity and Law 16.2 (July 2011).

[14] Ibid., 5.

[15] See, for instance, 'ICE returns Saddam Hussein ceremonial sword to Republic of Iraq,' US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) website, 29 July 2013 http://www.ice.gov/news/releases/1307/130729washingtondc2.htm.

[16] Although this author proposes certain 'temporary' solutions to counter such issues: see Conclusion.

[17] Russell, 'Why Should We Care?' 24.

[18] Article 1, UNESCO Convention, 1970.

[19] Peter Stone, 'Lessons Learned,' Comment, Museums Association, 26 March 2013 http://www.museumsassociation.org/comment/26032013-lessons-learned-10-years-after-iraq-heritage; Peter Stone is the professor of heritage studies at Newcastle University. See his article: Peter Stone, ' A Four-tier Approach to Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict,' Antiquity 87.355 (March 2013): 166-177

[20] Article 3, UNESCO Convention, 1970.

[21] Andrew Adler, 'Review of Patrick J. O'Keefe's Commentary on the 1970 UNESCO Convention,' Art Antiquity and Law 15 (2010): 281.

[22] See below, Part Three.

[23] Konstantin Parkhomenko, 'Taking Transnational Cultural Heritage Seriously: Towards A Global System For Resolving Disputes Over Stolen and Illegally-Exported Art,' Art Antiquity and Law 16.2 (July 2011): 288.

[24] Further emergency import restrictions in relation to Iraq specifically were introduced under the Emergency Protection for Iraqi Cultural Antiquities Act.

[25] Akhtar, 'Theft in Babylon,' 337.

[26] Excerpt from Ann Talbot's article, 'US Government Implicated in Planned Theft of Iraqi Artistic Treasures,' World Socialist Website, 19 April 2003 http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2003/04/loot-a19.html.

[27] Op. cit., 'Oriental Institute continues to support search for missing Iraqi artifacts a year after looting,' 6.

[28] Discussed below in Part Four.

[29] NSPA, paragraph 2314.

[30] 333 F 3d 393 (2nd Cir. 2003).

[31] Matthew Bogdanos, 'Thieves of Baghdad,' The Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq, eds. P. Stone and J. Bajjaly (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2009), 122.

[32] Patrick Steele, 'UK Government Under Pressure to Ratify Hague Convention,' Museums Association website, 1 May 2013 http://www.museumsassociation.org/news/01052013-government-under-pressure-to-ratify-hague-convention.

[33] Guideline 7.7, UK Museum Association Code of Ethics.

[34] 'Iraq, United States Reach Deal on Stolen Artefacts: Senior Ministry Advisor Baha al-Mayahi', Artdaily, http://artdaily.com/news/64013/Iraq--United-States-reach-deal-on-stolen-artefacts--Senior-ministry-advisor-Baha-al-Mayahi#.UgazixaPstg[/url].

[35] Hanaa Malallah, The Looting of the Museum of Art, 2003, acrylic, burned canvas, cloth and cardboard collage on burned wooden board.

[36] See lecture given by this author and Daniel McClean in conjunction with Southampton University and Ibraaz at the Mosaic Rooms (London), during the two-day conference entitled 'Global Futures Forum: Iraq and Iran 10 Years On'. Lecture is available to view at: https://vimeo.com/68220772.

[37] Matthew Bogdanos, Thieves of Baghdad (New York: Bloomsbury USA, 2005), 253.