Essays

Housing Archives

When Buildings Become Part of the Record

Beirut was never just the place where I conducted my PhD research. It would be more accurate to state that I used my dissertation project, exploring the fashioning of Armenian identification in Lebanon in the 1940s and 1950s, as a way to live in Beirut. Towards the end of my tenure there, I even entertained the idea of quietly abandoning the dissertation project and staying. I felt that I should remain, since my time in Beirut acted as a continuation of my family's past experiences with the city. My mother was born and raised in the city, my parents met each other there, and much of my family still lived within a few blocks of my mother's old apartment.

In addition to these personal connections that often distracted me from my work during the time I lived in Beirut from between 2007 and 2009, the ongoing wada3, or 'situation' – how the everyday tensions related to the political impasse between rival factions in the Lebanese government – pursued the city. Its constant menace obstructed the Lebanese political process and generated tension that enveloped the city and its residents. On any given visit, my family in Beirut would vacillate between calm and agitation depending on news gathered from the media, neighbourhood gossip, or self-proclaimed 'expertise'.

Helplessness produced this fluctuation, as everyone knew that no amount of information or analysis would prevent an outbreak of violent conflict. The governmental opposition demanded the power of veto and thus the ability to collapse the sitting government. Not surprisingly, the sitting government refused to comply and maintained their own stipulation: early presidential elections that would secure their authority. Yet, this impasse was not confined to the political realm. Party leaders seemed to thrill at the opportunity to give television, radio, and newspaper interviews, and used the media to communicate with their supporters while simultaneously distinguishing themselves from both political rivals and allies. Members of the public in turn appropriated these performances, furthering geographic, class and sectarian bifurcations. It became a common sight to observe signs pasted on the front door of a place of business politely 'requesting' that clients refrain from having political discussions.

The gathering of material for my dissertation occurred within this atmosphere of general unease. And when distrust between the inhabitants of the city manifested into violent conflict, it often made it physically difficult for me to reach the archives of the Armenian Church in Lebanon. The local city bus lines – wisely or foolishly – never altered their route because of the whims of political leaders. For this, I am forever grateful: after all, while my bus trips from Hamra to Borj Hamoud and Antelias were long, I never tired to watch the city as it transformed, from one street to the next, from one neighbourhood to the other. These movements made me feel like I was watching a zoetrope.

And the images of this zoetrope I imagined for the city transformed once I reached the archives. As my research largely took place in the Armenian Church archives in Lebanon, I spent much of my day interacting with priests, bishops and archbishops. The Armenian clerical establishment facilitated my work, though it was never clear to me if they simply tolerated my presence or if they sincerely valued my project. Nevertheless, I had unprecedented access to the personal notes of Armenian religious figures along with the official communications between Armenian Church and Lebanese state officials. In addition to these correspondences, I was able to see Armenian cultural records, including birth and death certificates, baptismal and marriage registers, and was also able to study the educational programs devised by the Armenian Church. Church officials allowed me to spend hours photographing, taking notes and studying these files, even permitting me to remain in the library after hours.

While I was very pleased and incredibly grateful for the access the Armenian Church officials granted me, one of my repeated requests went unheeded regarding the existence of archives surrounding the relationship between the Armenian Church and Lebanese government officials. I assumed that meetings must have taken place between Armenian Church and Armenian political party leaders and as such, documentation must have been produced. Yet if such documents existed, they were absent in the various files. Without this information, how could I decipher the way Armenian Church officials deployed their authority within the Armenian community in Lebanon? The Lebanese state regarded them as representatives of the community, but how did they communicate with the Armenian community? When I asked about the existence of such documents, I was asked in turn if I had completed studying the other records. I would answer negatively and try to politely justify my request with a mix of humility and humour, explaining that just as these meetings and debates would have occurred contemporaneously, I, too, needed to look at all the documents together.

I eventually came to two, equally frustrating, conclusions. Either these documents were likely destroyed – maybe purposefully or as an unintended consequence of the civil war – or, perhaps these meetings and notes were never recorded. And yet, when I asked different clergy officials if either scenario were true, they repeatedly assured me that they had the records. When pressed, they responded that I already had plenty to do thanks to the ample material they had already shown me from the other records. They were correct, to a point: I was definitely running out of time. I had finally decided upon a return date to New York and with it an end date to the collecting process.

I persisted with my inquiries but nothing changed. I still visited the archives to study the available documents, just as I continued to ask about the missing records. And then, a few weeks before I was scheduled to leave, the Prelate of Lebanon called me into his office to notify me I could finally see the documents. I was ecstatic. I then asked about the location of the papers, as I assumed they were housed in a remote location, given the difficulty of their procurement. The Prelate informed me that the adjacent building housed the archives on the second floor. Feelings of confusion suddenly attached to those of happiness. I had not paid attention to the neighbouring building, never thinking that the elusive documents were so close. Before I had time to really process this information however, the Prelate also warned me about the state of the documents. 'They are in a difficult state,' he said, 'and the room is dirty and unorganized.' I thanked him for his concern, and remember thinking to myself, 'how difficult could it be?' After all, the organization of the archives that I had accessed left much to be desired.

I couldn't have been more unprepared for what I saw the next day. I arrived at the archives ready to work: camera and notebook in bag. Two gentlemen met me: one, a church layman who helped organize the work schedule for the Prelate, and the other, a guardsman of the Armenian Church complex. They led me to the adjacent building, which was padlocked. When I asked what the seemingly abandoned building served as, the guardsman responded, 'Oh, in the past it's been everything: a school, hospital, offices, meeting place. But now it's just storage.'

Given its proximity to the main administrative offices of the Armenian Church in Lebanon, I could easily imagine how the building functioned as an office or a meeting space. It also made sense to me that it once served as a school. The Armenian Church administered all of the Armenian grade and high schools in Lebanon and designed the entirety of the educational curricula. This relationship between educating the Armenian inhabitants and the church administration extended to the location of schools as well, as most were built directly next to, or within proximity of, a church. However, it was strange to see such a historically integral extension of the church left in a derelict state.

As we climbed the dark stairs, I became even more interested in the building's own experience and how and why the archives settled there. Arriving at the second floor landing, I imagined how I was once a student in a school or a hospital. There were two long hallways with a series of doors that were ostensibly classrooms, though each door was individually padlocked. Old construction paper and remnants of children's art projects hung from the walls. We walked down the hallway and stopped at the last door on the left. The church layman asked the guard if he had the key ready and the guard unlocked the padlock and pushed the door open. We entered, myself with camera in hand.

Nothing could have prepared me for what I saw. The entire room was filled with boxes, stacked one on top of the other, hitting the ceiling. In their midst was a hospital examination table. While it served as the centrepiece of the room for me, it functioned as yet another surface upon which to hold/lay more boxes. And then there were the boxes themselves: labelled 'Philip Morris, Made in the USA', 'Kent Deluxe 100s', 'Lucky Strike: It's Toasted'. Seeing a room full of hundreds of American cigarette boxes in a makeshift hospital/school/archive in the middle of Borj Hamoud, Lebanon, was quite extraordinary.

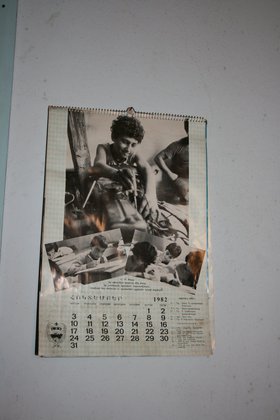

The lone window in the room did not offer much light. Instinctively, I looked to my right to see if there was a light switch, not yet realizing that whatever would be there would not have been connected to a power source. Beside the switch was an intercom with three buttons labelled: 'OR', 'lab', and 'x-ray', and next to that a calendar from 1982. I took a picture of both, and the guard suddenly began speaking about when the room functioned as a hospital examination room. His unexpected storytelling suggested he had been in the room as a patient in its prior incarnation. When I turned to him and asked for more information, he explained that during the Lebanese Civil War in the late eighties, as the fighting intensified at the edges of the neighbourhood, the building became a field hospital of sorts. It had become increasingly difficult for neighbourhood inhabitants to leave Borj Hamoud to receive medical care, so church officials decided to transform the building from educating the youth to treating the wounded and offering preventative care. Once the war was over, he went on to explain, the church decided to dedicate an adjacent – and larger, he stressed – building for the neighbourhood school and the school-turned-field-clinic slowly descended into its present state.

The inside of the building looked as if the employees and patients of the hospital had left suddenly and without warning. Whoever carried and stacked the many boxes did not move any of the medical equipment. I was astonished to see the expanse of boxes and how they reoriented the focus of the room, while blending with the medical equipment. There were even school desks dotted around. Nevertheless, church officials ignored the building's present life. This neglect, of both the boxes and the building's current function, was particularly tragic. While the previous incarnations of the building included a meeting place, a school, and a hospital, the layered experiences of the building converted the structure itself into an archive. Such an acknowledgement would have concurrently protected and honoured its previous states and various incarnations that helped to preserve the community.

In many ways, though, the building archived its own past. And this was to say nothing about the contents of the hundreds of boxes inside examination room #1. What might they reveal about the community's past? I scanned the room not knowing where to begin. I settled on the stack closest to me, creating some space to start lowering the pile. As I moved, the church layman stopped me. He had been under the impression, he explained, that once I saw the state of the room, I would 'understand' (he stressed that word) that it would be impossible to proceed. But I disagreed. I was too close to finding what I needed to leave now! I pressed against the wall to reach one of the only clear surfaces of the room. Moving some medical tools out of the way, I climbed the countertop and reached for a box. Seeing that I was either going to fall, drop a box, or both, the men quickly offered to help. They took the box from my hands and set it down on the floor. I remained perched on the counter, however, as the moved box now occupied what had been the last clear space left in the room. Realizing this, the guard and layman carried the box out into the hallway, where we jointly started to look inside. We found hundreds of sheets of paper, some in handwriting and others in typeface piled on top of each other. The first sheet I pulled out was a scribbled note from a meeting. I looked for the next page (or the one that ostensibly proceeded it), but found instead a completely different document. This one, a detailed personal information sheet, appeared to be an application for an identification of some kind, and was also incomplete. Under that, was a torn newspaper clipping that pointed me in yet a different direction.

Each piece of paper a historian finds is itself an archive, taking them to another time and location. A letter, a newspaper clipping, and minutes of a meeting: together these can be used to construct a story, which the historian attempts to convey. At the same time, the story weaves the objects together and links the archive and the historian. Each of the papers found in this one box, however, took me to a certain place: to a meeting between religious figures, a municipality office for an application procedure, or a school board conference for the approval of education curricula. Yet before I could shape each story, I was taken somewhere else by another (incomplete) record. And that was to say nothing of the tens of other boxes. As I dug deeper into the box, I became more and more confused by its contents, while the two men cautioned against me ruining the order of the contents. I immediately burst into laughter: 'That's precisely the problem. There is no order!' I could barely get the words out.

Yet they cautioned me anyway, the layman drawing attention to the black soot that had accumulated on my hands. 'You don't want to get the documents dirty,' he warned. And while I was shocked to see how much dirt accumulated on my hands, he failed to acknowledge it came from the documents themselves. Near the bottom of the box, I even found a bunch of charred documents. 'Why are these burned?' I asked no one in particular. The only response I received, which was unsolicited, came from the layman. 'Maybe we should leave,' he said.

I looked up, realized defeat, and slowly stood. I wiped the dust and dirt off my clothes, and silently left the room, waiting for the two men to lock the archives away. I watched the guard struggle and replace the box at the top of the pile, reapply the padlock to the door, and walk out. I solemnly left the building in silence, amazed at what I had seen. The layman interrupted my thoughts in front of the doors to the church administrative building and casually stated: 'Ok, good then. Now you have seen those as well.'

I was never able to access that room again. The only explanation of its contents I found came in an impromptu meeting with the guard the following day, who told me that the papers were haphazardly boxed at the end of the civil war and brought to Borj Hamoud for 'safe-keeping'. I thanked him; relieved I had at least some information, even though I sadly realized I would not get more than this, along with the memories and photographs of what I had seen.

So, I share them and my photographs with the reader. Even now, finished with the dissertation and employed as a professor, I often think back to those unsettled days. And while I feel no nostalgia for the uncertain wada3, I do long to return to that moment where I discovered piles of records that I knew could contribute to a better understanding of the Armenian community in Lebanon. What I saw revealed that my exploration of the fashioning of Armenian identity was both worthwhile and boundless. There was much to do and I had only begun. And because I was unable to physically access the room once more, my memories became all that remained to write of the potential of those records that rest inside cigarette boxes. Perhaps these recollections might aid in the preservation of those boxes, so that the records can be rediscovered and their contents made known.