Essays

Anachronistic Ambitions

Imagining the Future, Assembling the Past

In 2013, the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) held an exhibition based on Hari Kunzru's novella Memory Palace, in which Kunzru wrote about a future world where reading, writing and remembering are illegal. Commissioned by the V&A, the exhibition attempted to explore new ways of approaching a storybook, but it fell short of its aim (20 commissioned works illustrating themes of technology, nature, memory, truth, society and the financial crisis produced an incoherent message, especially without having read the book).[1] Nevertheless, what stood out was the premise of this novella: a world where documentation and memory is banned, and anyone caught in the act of remembering would be banished. The narrator of the story, part of a group of rebel 'memorialists', is charged with having 'Internet membership'. But, as Kunzru explains in the novel, authorities don't even know what words such as 'Internet' mean anymore. He writes: 'they use these words out of vanity, mostly. They are terribly insecure and terribly righteous.'[2] The story doesn't lack its own sci-fi nostalgia: the narrative refers to the time before the forgetting interchangeably as the 'blooming' or the 'booming'.

All the elements in this novel – righteousness, nostalgia, and conscience control – conjure up a certain reality. Comparable to George Orwell's much-referenced 1949 dystopian classic 1984, the context of these stories could easily be applied to the North Africa and the Middle East – where history is hidden, accessed with difficulty, rewritten at whim and, above all, where nostalgia is rampant. On an institutional level, only recently have hired researchers been preserving raw historical documents and narratives put together for newly developing museums by governments and their international consultants. Otherwise, it has become common practice for artists to forensically excavate the past in an attempt to lineate it with the present and move beyond official, government-propagated narratives. This essay, therefore, will adhere to Shumon Basar's observations that 'history is a portrait of the past and a manifesto for the future.[3] By engaging with the work of artists delving into either the past or the future, I will explore how ideas on self-image, ambition and capability are affected or formed.

Sci-Fi interrupted

Like knowledge, imagining the future is crucial in shaping it, and science fiction has been a major vessel. But, just as history has been shaped and suppressed on political bases, imaginations of the future have had a similar treatment, ultimately getting censored or lost. As of late, there has been a misleading adage that the Arab world has lacked a sense of science fiction,[4]'misleading' because it is simply untrue.[5] The question to ask is why there is this misperception, and why science fiction has been challenged and marginalized. Commenting on the a-politicization of the genre, writer Yazan al-Saadi has noted: 'The problem is that science fiction has not had the critical attention and role that would make it function as literature such as social realism had in Egypt or elsewhere in the world in the 50s and 60s.'[6]

These are interesting decades for him to specify. Townhouse Gallery Curator Ania Szremski points out that the Nasserist Egypt of the 1950s saw a surge in translation of works by Jules Verne and H.G. Wells.[7] Furthermore, Egyptian sci-fi short stories of this era were born out of prisons where writers and scientists were held in the same cells. Their inevitable discussions produced a canon of sci-fi titles with strong Islamic undertones and references to prophetic redemption.

Over the years, however, science fiction production in Egypt remained steady, with such examples as Youssef Ezedin's 1957 sci-fi radio plays and Nabil Farouk's popular pulp fiction series 'Future Files' in 1984, which continued to be written for over 20 years. In Farouk's tales, a core group of characters work to liberate planet Earth. The stories include elements such as time travel, artificial, intellectual and alien invasions and at times take on nationalistic tones of protecting Egypt from outside forces.

Beyond the patriotic, the politicization of the science fiction genre also enters the realm of the religious. Future visions, super powers, other worlds and artificial life are not appropriate concepts to the dogmatically minded. Writer Achmed Khammas discusses sci-fi elements in the way that they were applied to the Islamic settings of the region. At a science fiction symposium he attended in 1987, participants described the genre as 'stimulating in principle'. The general attitude was that stories should have strong adaptation to Islamic principles, with their motto being: 'A child's imagination should be liberated – but within recognized limits.'[8] Khammas goes on to explain that it wasn't until 2005 that an Egyptian journalist wrote a piece calling for schools to take science fiction more seriously and start including it in curricula, 'so that our Arab world can receive a generation of inquisitive scientists and academics.'[9] Khammas blames this exchange, between acceptance and rejection of the genre, on the Arab world's difficulties with imagination and vision. In a region of arbitrarily formed countries, where history is marred with failure due to power politics and economic interests, imagination has taken a back seat. The strong role of religion coupled with the drive to maintain the status quo of traditionalism, means that imagination does not fall on open ears.

Today, this type of curbing continues. In 2013, Arab literature blogger Marcia Lynx Qualey reported on the banning of one of Saudi Arabia's best selling books. A science fiction novel entitled HWJN was charged with 'blasphemy and devil worshipping' by the national committee for the Prevention of Vice and Promotion of Virtue.[10] This obstruction against the foray into scientific exploration became actual when reports on fatwas from Saudi Imams warning people against living on Mars emerged after 500 people from the region signed up for the Mars One mission.[11] Their reason for this ban was that people must be protected from danger and death, saying that this is what the Qur'an had advised.[12]

Nonetheless, Arabic science fiction is a tradition that has existed for over 1,000 years. It was produced in visual, literary and poetic forms, and did not remain insulated within the region. In fact, some of the ideas were so dominant, they have also been known to have an adverse affect. MIT historian and architect Nasser Rabbat noted a continued inspiration of millennia-old science fiction to be something of a plague limiting imagination towards a banal, Orientalist application.[13]

Talking about the future of urban development, he stated that 'the most enduring aspect of the Islamic city has been its fantastic quality',[14] citing examples such as the cities of Arabian Nights' influence on the eastern districts described in Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities. He points out that futuristic images from past centuries have been so influential that when Frank Lloyd Wright was called in to conceptualize a new, modernist Baghdad in 1957–1958 his rendition was very much based on al-Mansour's 1100-year-old Round City of Baghdad. The new city, designed to lie on two sides of the Tigris River, was more architectural 'but no less romantic'.[15]Though al-Mansour was inspirational to the futuristic fantastical feel of his vision, Lloyd Wright's 'modernist city', according to Rabbat, was heavily linked to a clichéd past.[16]

At this point, it is difficult to dismiss the influence of these bold visions on today's great growing cities of the Gulf, when it comes to achieving the previously unimagined. While some find the possibility of skiing indoors in a city like Dubai – which reaches 50 degrees-plus – fantastically awe-inspiring, other reactions from the general public have found these projects tacky. Further to this, the recently announced 'Aladdin City', an upcoming Dubai Creek project actually based on one of Scheherazade's 1,001 stories, has not garnered the most admirable responses.[17]

However, this mix between ancient fantasy and the hyper-futuristic has created one common reaction. From Bruce Sterling[18] to Sting,[19] the Gulf's city boom is commonly likened to science fiction. One photography artist, Martin Becka, played with this anachronism in his series Dubai, Transmutations (2007), in which he used a 150-year-old camera to create vintage-looking images of a futuristic present.[20] In 2009, Cedric Delsaux took the sci-fi comparison a step further, photographing landscapes of construction around Dubai and turning them into scenes from Star Wars as part of his greater, more international project, Dark Lens (2004-2009).

Delving into these utterances, Sophia Al-Maria's The Gaze of Sci-Fi Wahabi (2007-2008) – a work that manifests both in essay format and as an alter ego – and continuing research on 'Gulf Futurism', a concept she and artist/musician Fatima Al Qadiri coined, analyses why this comparison has become so common.[21] She puts spiritual and popular culture ideas into the practical development of the Gulf region today. She tells a story of a region that has transformed so quickly it jumped through time.[22] This non-linear path of progress, mixing tradition and hyper-modernity at the same time, positions the relations between the past and the contemporary within a long-awaited future.[23] Al-Maria explains that 'there's been a quantum leap and there's a temporal gap. The two things have been stitched together and there's a missing piece of history.'[24]

Forgetting the Past

This missing history, however, is far too real. Because of the dearth in accessible historical knowledge on the Gulf region, there is a common misperception that nothing was happening on the peninsula in the time between T.E. Lawrence and the recent futuristic boom. Government narratives easily fill this void with false histories that, in one way or another, serve to obscure concrete aims and visions.

The history of the pearling era in the Gulf is one such example. It is a chapter that has been highly romanticized as an era of wealth and 'identity' enveloped by the beauty of the sea, the glimmer of the pearl and the dignity of hard work. This story, however, covers up a reality of exploitation, slavery and intense poverty when tribal entrepreneurs accumulated wealth while divers, who died without question, passed on their debt to their sons. The Gulf's only popular work that stands as testimony to this history is the 1972 film The Cruel Sea by Khalid al-Siddiq. It tells the story of a boy whose father is bitten by sharks, forcing the boy into the trade in order to make enough money for a dowry to marry his love from a higher class. This film shows a harsh reality of class difference in a slowly urbanizing and far from ideal society in 1940s Kuwait, a story that is applicable Gulf wide.

This history, falsified into something great by governments through school lessons, museums and urban monuments, effaces past difficulties that have been overcome through demand for reform and eventual industrialization. There is a weakening of reality by way of nostalgic whimsy. But what is it about the 'identity' of this past that is so important to preserve in such a rosy tone?

Eric Hobsbawm's phrase 'a protest against forgetting' is applicable to many scenarios. In an interview, he explains this phrase in the context that contemporary culture works independently of the past, deeming it irrelevant. He argues, however, that the relevance of history is its roots in the personal and the social. Historical knowledge informs us so as not to repeat the same mistakes.[25] While false histories erase, nostalgia misrepresents and sentimentalizes past hardships and misery, leaving it negligible. This history of exploitative payment systems and disregard towards the worker are mistakes that should not be repeated. Once again, 'History is a portrait of the past and a manifesto for the future.'

So where does this place artistic practices that directly engage with ideas of history, collective memory, and amnesia? Thinking about the past via furtive imaginations, personal stories and found documents, an entire oeuvre of works has been aimed at opening up black-and-white narratives that have left us with clichéd and un-nuanced understandings of today's complexities, which include lineages of power, past labour issues, class existences and nation borders. One of the most standout examples of artists responding to erasure would be the great canon of works that respond to Golda Meir's 1969 utterance, 'They do not exist.'[26] As part of Zionist myth-making, this phrase sparked a long-term vision of defending the creation of Israel by way of erasing the fact that Palestine was an inhabited and urbanized country.

From militant cinema, such as Mustafa Abu Ali's 1974 film They Do Not Exist – made up of shots of children eating ice cream, women doing laundry, picking fruit off street trees and other everyday activities – to the myriad of personal archive projects, British archive projects, found image projects and so on, Palestinian artists have responded consistently and fervently to this vacuous phrase in an attempt to redeem their own reality. This 'cinema of visibility', as it has been referred to in various terms by Edward Said, Hamid Dabashi and others, continues as a need to document the mundane and present it as evidence of a people.[27] This fixation with clearing up the past has gone so far as to say that it has obstructed the vision of the future.

Among the few Palestinian artists dealing with a future vision rather than a purely historical one, which also engages with the question of existence as intertwined with the narratives of history, is artist Larissa Sansour. Her latest work, the polished nine-minute film Nation Estate (2012), sees a Palestinian citizen in the future, played by Sansour herself, coming home to her new 'state'. This state, however, is a skyscraper where the issue of checkpoints has been solved by elevators moving people from city to city. It also addresses the lack of space left for a Palestinian state, giving it a vertical form rather than a landscape. Sansour notes that her work 'borrows from science fiction: sci-fi deals a lot with post-apocalyptic condition: what do we do in the future? Obviously this is all informed by what is happening in the present. How do we deal with this condition?'[28]

In a sense, Sansour attempts to deal with the uncertainties that came with a history of failures and ruin. As such, Sansour admits: 'Even though it seems that what I am doing is surreal, this parallel imagined universe that I create is firmly based on the political situation in Palestine.' According to Sansour: 'this suggested or posited new world is an attempt for me to re-address the same Palestinian issues but in a different context.'

This displacement of context is evident also in the Novel of Nonel and Vovel (2009),[29] a graphic novel Sansour co-produced with artist Oreet Ashery, which questions playfully how art, as a super power of its own, can 'save the day'. This idea of artist as saviour, in the case of Sansour, relates to how far an artist might reconstitute a nation's lost history so as to provide a future that is as yet unforeseeable. In her work, the links between the past and the present weave together in the future. In Nation Estate Sansour echoes a party slogan from Orwell's aforementioned ominous novel 1984, that reads – 'Who controls the past, controls the future: who controls the present, controls the past.'[30] The threat of the phrase is the the ease at which the powers that be can erase the past, something Orwell described as 'more terrifying than mere torture and death.'[31]

Again, these anachronistic connections have been made all around us by various thinkers and artists. John Akomfrah's The Last Angel of History (1997) reminds us that, 'collecting bits of the past will crack the code of the future'. This work by Akomfrah sits in the sub-genre of 'Afrofuturism'. This term, coined by Mark Dery in his 1993 essay 'Black to the Future', relates to a literary and aesthetic genre that mixes fantasy and science fiction with the history of African-American oppression.

While not at all the same political situation, this narrative is comparable to that of Sansour's as an attempt to reconstitute a people oppressed to the margins. Dery, referencing pop culture by black Americans like Jimi Hendrix's Electric Ladyland (1968) and Sun Ra's Space is the Place (1974), saw space indeed as the place where African-Americans are 'asserting presence in the present and making clear they intend to stake their claim in the future.' Dery points out, that 'official histories undo what has been done' in terms of self-determined narratives. In parallel, Sansour's A Space Exodus (2009) brings us a female Palestinian astronaut, again played by herself, stepping out of her spacecraft, the Sunbird (a reference to the indigenous, Palestinian bird) rephrasing Neil Armstrong's famous line, 'one small step for a Palestinian, one giant leap for mankind.' She then goes on to stick the Palestinian flag onto the surface of the moon, claiming it. Like Sansour's reference to Palestine as 'post-apocalyptic', Dery points to the African-American experience as a 'sci-fi nightmare'.[32]

Forgetting the Future

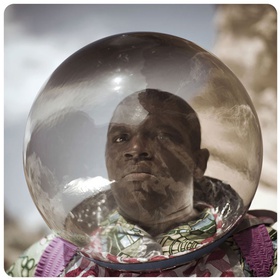

While forgotten histories might be more difficult to surface, uncovering what implications they may have had on the future remains a speculative sport that may be good to play. Photographer and photojournalist Cristina De Middel uncovered one such history through her project, Afronauts (2011). In Zambia, 1964, she one day discovered, a man named Edward Makuka Nkoloso started Zambia's Space Academy in an abandoned farmhouse outside of Lusaka. Although none of Nkoloso's dreams took off, his idea and audacity remain respectable. In her images, the setting, props and characters, all based on records and reports she encountered in her research, present a surreal vision of what preparing for a space voyage in Zambia was like. Her project does not celebrate the dreamer nor the dream, but it is fascinated by it. To De Middel, a working photojournalist, combining Africa with the international space race was something unique. 'I was disappointed in the image we receive of Africa so I wanted to go back to this original fascination that has very little to do hunger, war and famine – the normal images we get from there, so I wanted to balance that in my personal work,' she explains.[33]

In its own time, however, Nkoloso's idea was never taken seriously, not by the press nor his surrounding community. But what if it had been? It may be futile to ask whether the image of Africa would still be framed by poverty, wilderness and dependence if such a programme was used as inspiration rather than dismissed and buried. Despite its frivolity, Nkoloso had a strong idea that could have inspired other to be just as daring.

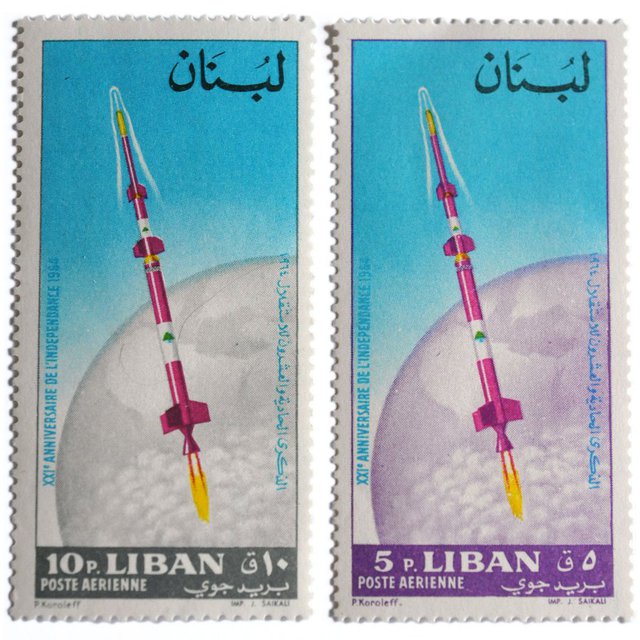

Similarly, and looking more particularly at the questions of history's implications, the Lebanese Rocket Society, an ongoing multi-media project by Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, brings up a story of possibility and achievements.[34] Yet it is repeatedly referred to as 'completely forgotten'. The society lead by physics professor Manoug Manougian for a few years in the 1960s, was a university science club that built and experimented with rockets. It started out as a programme based on educational curiosity and ambition. Rather than sticking to the classrooms and labs, Manougian pushed for funding, and got it, to encourage students to discover rocket science first hand. The programme was so successful, as the rockets got bigger and the propellants got stronger, they went further than was intended scraping the borders of Cyprus on one side and Israel on the other. The state even issued a stamp commemorating the project in 1964; ironically the same year Zambia's Nkoloso also had his mind set towards space. What followed, however, were dubious requests from the military and a few interested heads of (unnamed) Arab states. It was then, in the ominous year of 1967, that the project, going in exactly the direction that Manougian did not want, that the same government who had issued a stamp to commemorate the progress of the Society, ordered Manougian to stop the programme.

This history, which took place a mere 40 years ago, appears to be missing from Lebanese 'collective memory'. But it is not missing from individual memory, as the film itself shows us with its numerous interviews and re-tellings. While front-page news articles and stamps support the actuality of these events, this is a story that was omitted from the national historical narrative. Hadjithomas and Joreige have expressed that this project is their way of exploring the change in the modernist vision of the 1960s.[35] The film's epilogue is an animation that addresses the question: what would have happened if there was no intervention against the Lebanese Rocket Society and scientific curiosity continued? The animation shows a futuristic Lebanon that runs smoothly with high tech devices and a working transport system.

Of course, this is not to say that these aborted experiments are to blame for entire nations' developments, but the lineage and continuation of knowledge and imagination can be noted. In this case, there was a successful run in the field of science by a group of students and their professor, an achievement was made that should have been built upon rather than abandoned. The issue, therefore, is how to move towards the future while recovering the past.

Creative Futures

A podcast produced collaboratively by 98 Weeks, Lawrence Abu Hamdan and Nora Razian, part of 'A Radio Series on the Poetics and Politics of Language' is entitled How to be in the Future.[36] In this, Razian introduces the segment as being about 'science fiction and the future and politics of the future's projection'. Taking part in this recorded discussion, Joreige notes, 'When there is a rupture between the past and the present due to the change in representation as the one that we faced after the 1967 War, between Israel and the Arab world, there is a difficulty to project ourselves into the future.' He assigns this to a point in Hannah Arendt's preface to The Crisis in Culture, where she explains a moment of rupture where the position between the past and the present is compelled to propel into 'the non-future and therefore into the possibility of starting something new and inventing himself in uncertainty.'

It has been said many times before, history and memory – like time – is fragmented. And perhaps the future is too, to reference William Gibson, as Al Maria does in the aforementioned podcast, 'the future is here, it is just not evenly distributed.' The anachronisms of human existence make it so that all time in some dimension, comes together all at once. How do forgotten events fit in to our understanding of today? When we forget something, are we creating a void where a stepping-stone should be? Is 'now' the accumulation of all that ever was? The impossibility of grasping time with certainty makes us question eternally.

In many ways, time is relative to our understanding of ourselves. Histories that fall through the cracks are the histories that hit a wall, they have no future: where could Lebanon or Zambia have been today had they inspired people with stories of ambitious space races and wild possibility, rather than forgetting them? And where would the people of the Gulf be if they didn't have to compete with a dead past, romanticized beyond recognition by ministries who write the country's narratives? What could we have known from the pasts that have been bombed, bruised and buried?

It has become almost cliche to reference Edward Said's oft-repeated adage that history was written for us, mainly because of the passive attitude it implies. [37]In this time of accelerated 'future-ness', there is a current move to write and rewrite the past. Despite a general inaccessibility to history, artists and writers have been there to set it fee so peoples can reassess what has brought them to where they are, and in turn, decide how they are to overcome those very positions. And it is this overcoming that is today vital. The dystopia of forgetting is not about the past, but about taking control of history and moving on with as much knowledge and imagination as possible. It is about understanding the past so as to take control of the future.

[1] Hari Kunzru, Sky Arts Ignition: Memory Palace, Victoria & Albert Museum, 2013.

[2] Hari Kunzru, Memory Palace (London: V & A Publishing, 2013).

[3] Shumon Basar, introduction to 'Meanwhile… History,' Global Art Forum 8, Art Dubai (Doha, Qatar/Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 15-21 March 2014.

[4] Nesrine Malik, 'What Happened to Arab Science Fiction?' The Guardian, 30 July 2009 http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2009/jul/30/arab-world-science-fiction.

[5] Yasmine Khan, 'Arab science fiction shines light on current Middle East themes,' The National, 10 November 2013 http://www.thenational.ae/article/20131110/OPINION/131119978#full.

[6] 'Our Lines Are Now Open: A Radio Series on the Poetics and Politics of Language,' Ibraaz, 28 August 2013 http://www.ibraaz.org/projects/53.

[7] Ania Szremski, 'Science Fiction and the Technoparanoiac Drawings of Abdel Hadi al Gazzar in early 1960s Egypt,' MA dissertation, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2010 [unpublished].

[8] Achmed Khammas, 'The Almost Complete Lack of the Element of "Futureness"' Telepolis, 10 October 2006 http://www.heise.de/tp/artikel/23/23713/1.html.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Marcia Lynx Qualey, 'Saudi's Top-selling Sci Fi Novel Yanked from Stores,' blog entry, Arabic Literature (in English), 30 November 2013 http://arablit.wordpress.com/2013/11/30/saudis-1-selling-sci-fi-novel-reportedly-yanked-from-stores/.

[11] Rob Williams, 'Gulf imams issue fatwa warning Muslims not to live on Mars as it would pose "a real risk to life,"' The Independent, 20 February 2014 http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/gulf-imams-issue-fatwa-warning-muslims-not-to-live-on-mars-as-it-would-pose-a-real-risk-to-life-9141631.html.

[12] Amira Al Husseini, 'Saudis Banned from Traveling… to Mars,' Global Voices, 4 November 2013 http://globalvoicesonline.org/2013/11/04/saudis-banned-from-travelling-to-mars/.

[13] Nasser Rabbat, 'What do we need to Deconstruct?' Stages Journal 1 (2014).

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Mariam al-Serkal, '"Aladdin City" is next Dubai Creek project', Gulf News, 10 April 2014 http://gulfnews.com/news/gulf/uae/heritage-culture/aladdin-city-is-next-dubai-creek-project-1.1317870#.U0bYWCIzw0c.twitter.

[18] Fazeena Saleem, 'Doha high rises hide sci-fi plots' in The Peninsula, 2 December 2011, available online at http://thepeninsulaqatar.com/news/qatar/174329/doha-highrises-hide-sci-fi-plots-writer.

[19] Malcolm Borthwick, 'Dubai horse racing industry defiant,' BBC News, 26 March 2010 http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/in_depth/business/2009/business_of_sport/8584923.stm.

[20] Mairi Mackay, 'Dubai gets a retro makeover' CNN, 2 November 2009 http://edition.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/meast/10/28/martin.becka.dubai.transmutations/index.html?iref=mpstoryview.

[21] Sophia al-Maria, 'The Gaze of Sci-Fi Wahabi: a theoretical pulp fiction and serialized videographic adventure in the Arabian Gulf,' blog entry, Sci-fi Wahabi http://scifiwahabi.blogspot.co.uk/2008/09/introduction.html.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Karen Orton, 'The Desert of the Unreal,' DazedDigital, April 2013 http://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/15040/1/the-desert-of-the-unreal.

[25] Hans Ulrich Obrist interview with Eric Hobsbawm, Warburghiana, 2007 http://www.warburghiana.it/file/41_1.doc.

[26] Golda Meir, 'Mrs. Meir Bars Any Deal for Israel's Security,' The Washington Post, 16 June 1969, section A: 15.

[27] Hamid Dabashi, ed., Dreams of a Nation: On Palestinian Cinema, New York/London: Verso, 2006).

[28] This and all subsequent quotes were expressed in an interview with the artist for Platform 007 unless otherwise stated.

[29] Larissa Sansour and Oreet Ashery, The Novel of Nonel and Vovel (Milan: Charta Art Books, 2009).

[30] George Orwell, 1984 (New York: Penguin, 1949), 37.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Micah Yongo, 'What is Afrofuturism?' Media Diversified, 1 January 2014 http://mediadiversified.org/2014/01/01/what-is-afrofuturism/.

[33] 'Cristina De Middel, Deutsche Borse Photography Prize 2013,' London, Photographers Gallery https://vimeo.com/64393165.

[34] Lebanese Rocket Society, dir. Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, About Films, 2012.

[35] Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, 'On the Lebanese Rocket Society,' Broadsheet 43.1 (2014) http://www.cacsa.org.au/Wordpress/yoo_bigeasy_demo_package_wp/wp-content/uploads/Broadsheet/2014/43_1/43_1_Lebanese_Rocket_Society.pdf.

[36] 'Our Lines Are Now Open,' op cit.

[37] Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1978).