Interviews

A Militant Cinema

Mohanad Yaqubi in conversation with Sheyma Buali

In this interview for Ibraaz, writer and critic Sheyma Buali talks to Palestinian filmmaker Mohanad Yaqubi about his latest project, Off Frame (2013). Working with found documentary footage of the first two years of the Lebanese Civil War shot by the Palestine Film Unit (PFU), these precious reels were lying neglected in Italy until Yaqubi re-discovered them in 2011. He has since brought them to life again to show the depth of Palestine’s filmmaking history, its role in shaping Palestinian identity, and its ties to the wider Third Cinema movement. What unfolds here is a story of a specific form of ‘militant cinema’, in which ‘reels were treated as ammunition and a narrative of commitment and circumstance in which images revisit a history once thought lost to the vagaries of war unfolds. To this, Yaqubi adds his own question, namely: Was there more revolution in cinema than revolution itself?

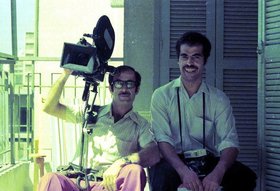

In 1968, a cinematic movement began life in Jordan, which still stands as one of the boldest in Arab visual cultural history. The Palestine Film Unit (PFU), a collective made up of filmmakers and researchers including Mustafa Abu Ali, Sulafa Jadallah, Hani Jawhariah, Salah Abu Hannood and many others, came together with support from the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). Its aim was to document everyday life and the extraordinary events that occurred regularly in Palestine during this time. The camera became a tool in this struggle for nationhood, a way for Palestinians to show the realities of the struggle and to take control of their own image, one that was being torn apart by Israel’s systematic erasure of a culture and people.

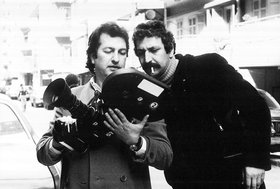

The movement was part of the greater global militant filmmaking community, with icons of world cinema from far corners sharing technical expertise and insights into clandestine techniques. Among these were Jean-Luc Godard, Chris Marker, Santiago Alvarez and Koji Wakamatsu. Becoming pivotal elements in the Third Cinema movement, the filmmakers in the PFU were not working as artists, or even as documentarians: they were making films to inspire the revolution.

The footage, both of the struggle to create a self-determined image and of revolutionary activities, was treated as a quintessential part of the ongoing fight. It was viewed as a threat to the newly-born state of Israel; a project for which the filmmakers risked their lives producing and protecting.

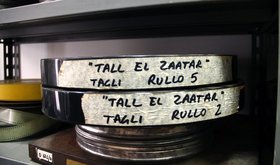

In 2011, Mohanad Yaqubi, a Ramallah-based filmmaker, made the staggering discovery of 1500 metres of footage (around 200 reels and 150 kilograms) shot by the PFU in the first two years of the Lebanese Civil War, including the destruction of Tal El Zaatar camp in Beirut, Lebanon. The footage was in Rome, neatly left where it had placed been in 1977 after it was smuggled out of Lebanon. Yaqubi’s upcoming film project, Off Frame, aims to look at this history through this found footage and to question this cinematic mode and its abrupt end, marked by Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982.

Sheyma Buali: The Palestine Film Unit (PFU) was a major force in militant cinema. It was responsible for taking control of the Palestinian image, moving it away from images of victimhood, and making it synonymous with that of the fighter. Can you tell us a bit more about this history?

Mohanad Yaqubi: The Palestine Film Unit (PFU) came together as the filmic arm of Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). After a few reformations, it eventually became the Palestinian Cinema Institute, which was part of the Unified Media, the information arm of the PLO. They made films until 1982. When the Israeli army invaded Beirut, the PLO and its units had to wrap up and move elsewhere. Since the process of expulsion was rapid, a lot was left behind, including the cinematic archive, which they thought was too heavy and left it with a view to returning to it later on.

But what is significant about such a revolutionary institution is that with every film they made, they would make around 70 copies and send them out to PLO offices around the world, student unions, worker unions, political parties, festivals and so on. So, mathematically-speaking, there are 70 copies of every film scattered all around the world.

SB: You recently found rushes for a film documenting the Lebanese Civil War 1975–1977 in Tal El Zaatar, in north-east Beirut. How does this footage differ from the general style of PFU footage?

MY: When the PFU were shooting film, there was no script or pre-determined idea; they were just documenting the daily life of the revolution. If someone later came up with a script because they needed to make a film about a particular event, raise awareness or send a political message, they would go back to that same archive, choose the material and then edit the movie together. The main thing that differentiates the films is the voice over. In most of them, the images are the same, just edited differently.

SB: The rushes you found were actually made into a documentary, Tal El Zaatar (1977), which ended up in Rome, and the movie itself is in Italian. How did that happen?

MY: Many Arab filmmakers would develop their films at Studio Baalbek in Beirut, including the PFU and other militant filmmakers. The custom was to leave the negatives there, after the film was cut and screened. But in 1975, the studio was hit by Falangists and almost all the negatives were burned. That was why, in 1977, after documenting the Civil War for two years, Mustafa Abu Ali didn’t leave the rushes in Beirut; he thought it would be safer to take them to Italy.

The story of how he got the footage to Italy, though, is the interesting part. In 1977, the airport in Beirut was closed, the city was already divided into east and west, and Mustafa wanted to take more than 400 reel tins out of Beirut to Rome. At that time, he didn’t even have a passport. Together with Randa Chahal, another Lebanese filmmaker, they took the reels exactly the same way weapons and arms were smuggled, out of Sidon in southern Lebanon, and from there they took a ship to Cyprus. While at sea, they were caught by Israeli navy forces but ‘luckily’ they were not searched. They had hidden the negatives at the bottom of the ship. By the time they got to Cyprus, they had to fly to Rome. At the airport in Rome, the footage was confiscated but the Italian Communist Party, who actually helped arrange this trip, managed to get it out, develop the negatives and make the documentary, Tal El Zaater. To me, it is a very powerful metaphor for militant cinema, when negatives are being physically dealt with in the same way as ammunition.

SB: You are based in Ramallah. How did you figure out that these rushes were still in Rome and actually get your hands on them?

MY: I was reading the diary of Mustafa Abu Ali and in the diary he says ‘we took the negatives out of Beirut to Rome’. So I thought to myself, where are the rushes in that case? I got in touch with Khadija Abu Ali, his wife and also a filmmaker and researcher; she told me she wasn’t sure but they were supposed to be in Rome. I had also spoken to the French filmmaker Serge Le Péron, who was a friend of Mustafa’s who told me that Mustafa worked in Rome at this production house called Unitel Films, but they no longer existed. So I contacted the militant filmmaker Monica Maurer, who said that this production house dissolved into AAMOD, a liberal movements archive. They hold films and negatives from all over the world: from the Italian communist archives, from Vietnam, Laos, Cuba, a lot from workers’ movements, strikes and so on. So I asked them and they took a month to check but they came back to me saying that they had the negatives, they were on a shelf, and had been there since 1977. So I flew there and made an appointment. I couldn’t watch everything but I knew they were there so the next step in the mission was to re-scan them, digitize them, and bring them to life again.

SB: The militant image developed by the PFU used quite a bit of iconography, building an aesthetic of self-determination. Elements such as prominent positioning of women, the use of Kalashnikovs and so on; can you describe the footage you saw?

MY: The rushes are in very good condition as they were only used for one documentary and not all of them were used in the end. I’ve only seen two reels out of 200, so far. One of them was an interview with a group of fighters from Tal El Zaatar telling their experiences, and there was one beautiful female fighter, holding a Kalashnikov, smiling and talking a lot about her experiences, how she will continue being a fighter, how she lost her family in the battle – her name is Zeyneb.

Another reel I found showed a port that was bombed by the Israelis. There were people checking the sunken ships in the port, a demonstration in front of the port, but I couldn’t hear what they were shouting – there are magnetic sound reels but they are not connected yet. It’s a big job.

SB: Mustafa Abu Ali is an influential force within the PFU. Can you tell us a bit about your relationship with him?

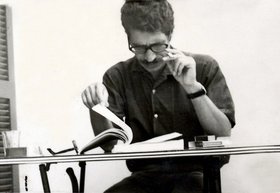

MY: I had just finished my first short film Fix (2008) when I became a member of the board of directors of the Palestinian Cinema Group, which was reestablished in 2004 in Ramallah. Through that I was able to get to know Mustafa Abu Ali. A year later, I did the subtitling for his 1974 film They Do Not Exist. He sat next to me the whole time I was working on it. It’s a 20 minute film, and usually that would be a day’s work, but I spent three days on this film because Mustafa was telling me the story behind every shot. I was amazed by his stories. When I went to do my masters at Goldsmiths University in 2008, I attended a lecture about Third Cinema and Third World cinema. The tutor started to speak about Mustafa as an academic star. I hadn’t known any of what she was telling us. I was embarrassed but also proud. So I did a bit more research about him and suddenly a whole world opened up to me, and it wasn’t just about Mustafa. It was a unique mode of production, an underground world of cinema that was connected and active and very genuine, working together, whether it was the Red Army in Japan, stealing negatives from a factory there and smuggling them to Hong Kong to be developed, then distributing them to other places via the PLO, or whatever. It was a whole network. When they made the films, they would develop them with the help of the French Communist Party and with the help of filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard. Chris Marker was also involved in helping filmmakers from Latin America. There was an active network, and the Palestinian filmmakers were a very dynamic part of it. They had all the tools, they didn’t have the money, but they knew how to smuggle things. For example, they made six or seven films in Adan in South Yemen.

SB: Right now, there is limited knowledge of Arab cinema's participation in global movements. With the current growth in popularity of Arab cinema, what we read is contextually short-sighted and industry-led. It is often as if the relevant historical moments in cinema are being forgotten. What is your motivation in your research and reviving this era of film?

MY: Usually when we study films, we study international films. We don’t have our own heritage in film, we are young filmmakers and we are not connected to that period. When it comes up and you see what was made, the ideas and discussions, you discover that there is a heritage that is still valid today; maybe even more so with digital filmmaking. The PFU was the first instance in Palestinian history where Palestinians were creating their own image and were in control of it. That would be very useful to think of and revive today, as something to hold up to this post-Oslo Accords sort of cinema. Also, the filmmakers we grew up learning about, the ‘fathers’ of Palestinian cinema, never mentioned any of the cinematic work that was done before theirs that was aesthetically and conceptually rich. Even people in the Palestinian Authority (PA) here in the West Bank, mostly comprised of ex-revolutionaries, would agree with that.Then there is the pressure from Israel that this is all propaganda and that it is anti-Semitic. Suddenly, we have no history – not only in cinema, but in all areas of life. I’m talking specifically about West Bank and Gaza.

SB: What do you think of Palestinian cinema of today?

MY: The militant period produced a cinema of the oppressed while Oslo cinema is one of victims. Recently though, it has been changing. Recently we’ve seen other films like Kamal Aljafari’s Port of Memory (2010) and Abdelsalam Shehadeh’s To My Father (2008), and these two movies specifically brought Palestinian cinema out of its logic of victimization, talking very personally but at the same time connecting the personal to the historical, both visually and politically. To My Father is about the history of studio photography in Gaza, from the 1950s till today, and Port of Memory documents cinematically the history of the systematic gentrification of Jaffa. Back in 2004, Godard said the Jewish people became fiction while the Palestinians became people of documentary in his film Notre Musique (2004). We are really into documentary, not into fiction; we still haven’t explored that area very well.

SB: There is a trend today for reflexive documentaries, in which the filmmaker is part of the story, allowing the audience to follow their journey. To what extent will you be part of your film?

MY: Basically I will be working on the Moviola editing machine and cutting the history from films. I will not be there in person, but it is my voice reading the diary of Mustafa Abu Ali.

SB: Your film Off Frame will be made up of footage shot to document a specific event but talking about something a bit broader, creating a meeting point between footage of that event and the re-use of the footage to tell a more general historical story about cinema and a particular cinematic movement. So in essence you will be going back and forth between the diary, the physical existence of the film, the raw footage, and the actual film that was made out of the footage. How do you plan to script out this interplay?

MY: My biggest question is how to turn the research into a film. The first layer of it will be the film made out of the rushes of Tal El Zaatar that I found as the last film made by Mustafa Abu Ali and the PFU. From there, we’ll go back and see the whole history through it. Within that complex we are hearing the history and seeing how political events influenced the aesthetics to reach the point at which the film was made. It was made to explain the PLO’s position in the Civil War, which wasn’t called a ‘Civil War’ at that time. The term ‘Civil War’ didn’t really start being used until after 1982. At that time, it was the struggle of the avant-garde and national forces against the Falangists and the imperialist forces and its arm in the region. In that period there were a lot of secular Lebanese and people from all over the Arab world, working with the Palestinians in sharing the struggle and supporting the revolution. It is hard to understand what happened to the films and the movement without understanding the Civil War and the actual history of Lebanese politics. But it should be said that I am coming from a Palestinian point of view, it is a Palestinian film and I’m looking at how that affected cinema. My main question in the film can come down to this: Was there more revolution in cinema than revolution itself?

SB: What is your answer?

MY: There were more revolutionary people than a revolutionary institution. The Palestinians, their Arab friends, and their global network, they were revolutionaries, they were active, they didn’t even get salaries. They were sleeping, eating, moving around always with the cameras and documenting everything, then coming back and editing it. When they didn’t have the chemicals to develop the negatives they would find a solution. When there was no electricity to recharge the camera batteries, they would think of ways to get different kinds of cameras that didn’t need electrical recharging. That is what they were talking and thinking about. That was the spirit of the revolution. If you have only one reel of negatives and you are in the middle of a battle, what are you going to shoot? What are you going to do? How are you going to make a film out of this? The cine-tactics that developed according to the needs of the revolution are revolutionary in many senses. But following the contrast between these people and the political institutions that were running the show, I don’t call it a revolution anymore; I see it as a struggle for representation. The PLO leadership was in conflict against the Arab countries, mainly, and in front of the international community to represent the Palestinians. The political leadership wasn’t the idea of the base; it was thinking and believing that it would lead a whole social, political and economic change in their society. The role of women and other areas were focused on. And they could do it, not because of the institution but because of what they were doing. If you take a look at Lebanon, before the PLO came to Beirut there was almost 90 per cent unemployment among the Palestinian refugees, after they arrived it went up to 80 per cent employment with 60 per cent being women. They were working in everything from tailor factories, food factories, arms factories – all this was in the refugee camps. After 1982, we know what happened – it went back to the way it was before the 70s. People were refugees again without work, without hope, without anything to do.

SB: So you think the images really had that influence?

MY: Yes I do, on different levels and in different stages. Say for the first period between 1948 and 1967, Palestinians were lacking visibility; to quote Elias Sanbar, '1948 was a moment of invisibility not occupation, it was a complete disappearance. For someone who is invisible, their weapon would be a camera’. That is why, when the revolution was taking shape, especially at the end of the 1960s, it was common for a Palestinian, before joining the revolution, to get photographed with a Kalashnikov in a professional studio without covering their face. But that would totally contradict the basic tenets of any armed underground movement. The image was very important for the Palestinians to come back to again. The PFU were using this image and screening it in different places, particularly refugee camps, while the political commissar would be narrating: ‘OK, so you’ve lost your land, you were attacked by Zionists, the only way to come back is by holding guns’. That mobilized people a lot at that time, many people have said that they joined the struggle as a result of these images. At that time, there was no TV, but there were big screens in the camps.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency used to screen old Egyptian films in many of the camps every Thursday night. These Egyptian fantasies were projected onscreen and showed scenes involving big houses, dinner parties, beautiful women – all the things that Palestinian refugees didn’t have. Cinema became the place of a dream. When the PFU made their first film, they went on a Thursday night and screened their militant film. So when the Egyptian fantasies were replaced by the image of the ‘fedayeen’, the audience believed in it and joined in it because suddenly it was in a place where only dreams occurred. What Mustafa and Khadija told me was that they believed many people joined the revolution because of these screenings.

Mohanad Yaqubi was born in 1981. He graduated from Birzeit University in 2004 with a mechanical engineering degree before going to London's Goldsmiths College to study film, graduating in 2009. He has directed several short films, both fiction and documentary and is a founder of Idiom Films. In Ramallah in 2006, he curated the photographic exhibition The Art of Waiting with Yazan Khalili, which was inspired by his time spent waiting for trains after he was awarded a bursary to study art in London by Charles Asprey and Kay Pallister.