Interviews

Role Play

Oreet Ashery in conversation with Amal Khalaf

My first encounter with Oreet Ashery's work was at Goldsmiths on a Thursday evening in 2007. I was sitting in the darkened lecture hall, faced with the artist on a stage and a huge projection behind her dressed as an Orthodox Jewish man dressed in a black hat, with full beard, cupping a breast that is sticking out of a black suit: Self Portrait as Marcus Fisher I (2000) (one of Ashery's many male alter egos and fictional characters that have included an Arab man, a black man, a Norwegian postman, a large farmer and a false messiah). Confronting social, ideological and gender constructions, the London-based and Jerusalem-born artists' politically engaged, complex, and participatory work always occupies a contested socio-political territory, be it interrogations into migration, religion, feminism, queer politics, or class. Though earlier projects situated Ashery as the performing body, recent projects such as Party for Freedom (2011–13) and The World is Flooding (2014), and Staying: Dream, Bin, Soft Stud and Other Stories (2010), have seen the artist take her body out of the work. These large-scale productions have been performed in museums and institutions around the world, moving away from one body and voice to works with many bodies and many voices.

Amal Khalaf: Your practice deals very much with migration, and the constant negotiation between outsiders and new spaces. One of your first projects, First Generation (1992–1996), was carried out between 1992 and 1998: you ran a black and white darkroom at the community centre located at 1a Rosebery Avenue, London. How do you relate to the theme of migration?

Oreet Ashery: That's a really good question, I rarely get asked about the migrant's identity in my work, which is interesting.

I'm an immigrant. I came to Leicester from Jerusalem in around 1987. I was young: 19. I imagined that England was like what I'd seen on television: carriages and horses and big London streets with impressive architecture. Leicester was different to what I imagined; people had a different accent to what I'd heard on TV. Later on, I came to understand that England was full of different accents.

AK: Where did you live in the first instance?

OA: I lived in Highfields, known at the time as the Asian ghetto. Everyone in my street sat on their door ledge and had their door open; children from the street came to my house to say hi; families worked day and night; many did not speak English. There was something soothingly familiar and Middle Eastern about the community: a kind of warm and open street culture. But it was still quite a shock to my system, arriving in England. It was hard leaving everything behind; my family, friends, my environment, the food and smells and music – everything I was used to. But I wanted to leave Israel; I wanted to leave because I wanted to get out of the army – I was in the middle of long compulsory training as a weapon instructor at the time. Because of the politics of the Occupation, I had been marching with Peace Now since the age of 13 and the army made me feel mentally unstable. So I asked my British partner at the time to marry me. This got me out of the army and allowed me to come to Britain. Both involved a great deal of bureaucracy. It was a long process.

Only in retrospect have I realized that I've always been interested in minorities within different minorities: sexual minorities, gender minorities, ethnic and economic minorities – outsiders. The most consistent thing in my work has actually been immigrants. Things overlap, so whether it's immigrants with a particular sexual orientation or whether it's immigrants with different musical interests, it's always been a constant in a strange way. I've always felt some connection with other immigrants because of being one myself. I notice the difference between meeting people with whom I share this particular immigrant sensibility or subjectivity, and those who were born in Britain. You haven't watched the same childrens programmes, your cultural and emotional frame of reference is different, your confidence in using the English language is different. Also, this feeling of being a guest produces interesting side-effects, like not feeling as free to criticize the government, knowing how much worse it is where you come from, not feeling like you can really have a say, or feeling like a fraud if you did say something because you are not from here. You often end up producing your own networks based on more improvized structures, or suddenly shifting into your first language when you are angry or excited, and looking for simulated experiences in London that remind you of home. I feel completely connected with those experiences.

What always fascinates me is the self-knowledge that minority groups of people develop and have. It's largely unknown in the mainstream. It's not what the media tells you, or what is written in books: it's literally how people collect their own knowledge about a situation. For example, when I worked on the project The World is Flooding, the participants, mainly asylum seekers, shared a lot of information about food vouchers and the Azure system. They spoke about how to make the best of it, how to find cheap food stores and what to do when the voucher does not work and you are in the queue with your food at the supermarket (I see that often in supermarkets, it is an appalling and humiliating system).

I've always been interested in survival strategies, particularly for immigrants and asylum seekers. In these situations, so much is about you and a lawyer, you and an officer, you and the law: it is always one migrant against the authority so I always try to work in a group to break that alienation, so that knowledge comes together into one big bucket. It's not just about saying, 'This is my story', because those stories are used in court cases in a very invasive way. When I work with participants in workshops we put all the stories together and work with them. I always try to use people's stories as part of a fiction. I do it in workshops in a way that it becomes more of a material to work with and a distance develops.

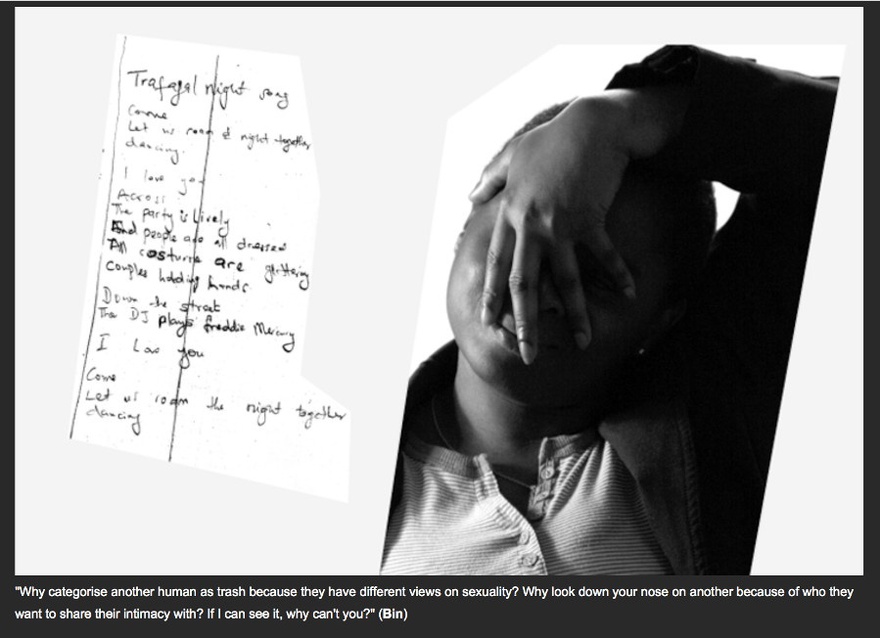

For the project Staying, an Artangel commission in 2010, I worked with lesbian asylum seekers. The project was set up to explore ways in which identities are constructed around the conditions of their arrival to the UK on the basis of sexual orientation. When an asylum seeker enters the UK on grounds of sexual orientation they have to write a 20-page report that proves their orientation and also the risk to their lives as a result. It is a very hard document to write, as there isn't always hard evidence. Sometimes it is just a feeling, a desire, and there is also a lot of shame, guilt and trauma attached to it. Sometimes people can't practice or prove their orientation because if they did so they would be killed or raped.

I worked with these women in developing alter egos. This created a level of a fictional distance that enabled us to write about their experiences.I made sure that we wrote as a group and not individually so as to not repeat the home office experience. This was a collective and inter-subjective form of writing. The text that was produced spoke so much about their traumatic experiences and their sense of desire. Later, the Home Office partly embraced this project as legal evidence. The text was used in groundbreaking ways in asylum seeking court cases for those who took part as evidence of their sexuality. This made it clear that creative writing can be more revealing than the supposed 'objective writing' that is expected in the bureaucratic business of immigration and asylum seeking.

AK: Really?

OA: A lot of people think that immigrants pretend to be gay to get into the country, when its actually one of the hardest ways to get in. Through writing fiction and erotic poetry, we actually made a text that was useful in court and worked in their favour. If one reads the texts, one knows that these people are not making it up. The beauty of fiction is that it is so truthful. I was amazed that it was used in court cases and it opened up this whole thinking process for me in terms of how the way asylum seekers have to legally prove their identity isn't working. They usually end up in detention centres for years.

AK: It really touches on the invisible things that you don't see because of the way that 'immigrants' – migrants or refugees – are represented and the way identity has to be played and performed. It is, as you said, about making structures that give people a way to read their own situation.

I wanted to talk more about how you work collaboratively in your work. On Staying and The World is Flooding, for example, you said that the workshops for these projects triggered all of these new thought systems for you in terms of collaboration and the formation of groups or communities. Do you have a specific approach when working with people?

OA: Yes, I have some ways of working that I guess are consistent. For example, the relationship with people that I work with is really important to me and it's always very individual. I get to know people. They become part of my life, to an extent, and then the people themselves create friendships with other people in the project, forming local communities that have a life outside the project and after the project. This is really important to me: that the projects have sustainability to them. Otherwise, you are just a visitor dipping into people's hardships. There is too much of this in art.

I wrote Raging Balls in 2008 and it has been performed many times since. The performance is based on a scripted rant made partly of a description of an unjust Stop and Search scenario (this was at the time when the first anti-terrorism laws came in). The other part is about artists traveling to areas of conflict and poverty away from their own surrounding to produce highly aestheticized video works. I had a lot of rage about it at the time as I felt it was exploitative. There were also hard paper balls thrown between the audience and two other performers during the rant, so it is a bit of a riot. I wrote the text with someone I know in mind. My performances are always made for specific people or derive from specific people during workshops. However, in China we used a Chinese performer I didn't know because I wanted to have the Chinese text and the context of state control in the censored translation.

The World is Flooding was a project performed at Tate Modern Turbine Hall in 2014 mainly by asylum seekers, from Freedom from Torture, UK Lesbian and Gay Immigration Group UKLGIG, Portugal Prints/Mind Charity, and those who came individually (the full performance can be seen here). Over a period of months, we collected and developed material together in workshops, producing forms of knowledge. Then we mixed and swapped the stories so that one person might deliver another person's story in the performance, which is not as simple as it sounds; people's stories are embedded in trauma and they become attached to them.

There are always those types of methodologies and interventions in the structures of my performances I'm always looking for a distance in a positive sense. It's not about 'this happened to me', 'that happened to me', or 'I'm a victim of this or that'. It's always about a more creative and reflexive approach that happens through distancing. Whether it's a character, an alter ego or whether it's an already written play, or performing someone else's text, there's always that sense of distance. Creative ways of fictionalizing and distancing allows participants to share real and useful information without feeling sorry for oneself or shameful. That never works.

AK: I wonder if you could speak more about your references. I feel like you think outside of performance art histories and that's why I find your work so interesting, because you're always coming from all these different places.

OA: Sometimes I think, yes, the work is maybe too complicated for that reason but I do have a wide range of interests. This is also partly because I'm interested in people, not just in art and culture. It expands the range. I get so inspired by people and what they do and say. I will literally talk to anyone.

I do have an interest in what Dada, Bauhaus and Andy Warhol did to interdisciplinary practices, and I am interested in histories of feminisms of course, like the Riot grrrls. I have a soft spot for George Kushar and Charles Ludlam and how they created communities and used a trash and DIY aesthetic. I am interested in fashion: Walter Van Beirendonck influenced the ponchos for The World is Flooding. I am also interested in music, from post punk, electronic, to classic contemporary to Jazz fusion, and always commission original music for my work. I am interested in politics and protest, in political speeches and the apparatuses of power and celebrity, and watch reality TV. I am interested in many writers, and am currently obsessed with Rebecca Solnit and Ursula Le Guin. I am influenced by food and the memory of my childhood environment. Then there is cinema and certain cinematic moments that I find thrilling. I could go on.

AK: What were your first experiences of performance?

OA: My own performances, really. I was a witch when I was 10 because of this book that I read and was so influenced by.

AK: Which book?

OA: It was a children's book about a girl who was a witch. I thought I was a witch, a good witch, so I tried to be one. I performed rituals with friends, trying to help them in school, like I made a drink with chalk and hot chocolate for a friend hoping that she would use chalk better whenever she was asked to go to the black board. Sadly, the girl I prescribed this to got ill from drinking the chalk and I learned my lesson and stopped this witch practice. But these kinds of social rituals informed me greatly, and I still do similar things in my work, only with responsibility.

I also did a lot of walking as a child and a teenager. I walked in Jerusalem everywhere and really crossed territories, from Orthodox neighbourhoods, to Palestinian neighbourhoods. This was another early formation of my practice.

AK: Were you walking on your own?

OA: Yes. I think this really formed my practice in terms of intervening into public space. Walking implies a gender intervention, because you are aware of that fact that you're a girl and that you're too young to be walking alone. You don't fit in, everybody is looking at you and you already realise it, like you're an artwork. You are not meant to be there and you know it, and everyone else knows it. As I got older, I started dressing in my dad's clothes to go out because I just thought that I would feel more confident because I'd be more like a man. But of course, I just looked stranger because I was wearing really big men's clothes.

AK: Did you feel more confident when you were wearing these clothes?

OA: Yes, I felt more like I was dressed in a costume, not as myself, so that distance helped a lot. I remember people would ask me questions and I'd make up stories. There was something about me that made people stop and ask me things about my whereabouts. I didn't tell lies; I literally just fictionalized things. I remember once on the bus a guy asked me: 'why are you on your own?' (I was too young to be on my own) and I said that my dad is a really important general in the army and he is always away so I have to travel to town alone. This was a lie. In fact, my dad has never been in the army and in a country where everyone has to go, this fact has always haunted me. Fictionalizing became a practice as well.

My first real performance art experience was in a town in Israel called Akko, which is mixed. It's an Arab and Jewish town and they use to have a performance art festival every year, perhaps they still do. I went there when I was maybe 16, on my own. I'd never seen anything like it. There was this one work performed to the song 'O Superman' by Laurie Anderson: a naked person sitting on a chair and another person who slowly covered them in bandages. I was blown away. I'd never heard of music like that or seen anything like it. It wasn't TV, it wasn't theatre, it wasn't film. Then I had to hitchhike back home at night, but there were no more cars on the road as it was late, so in the end, I just slept under an apartment block, in a garden. In my mind, that was part of the performance experience I had, and I think about this when I make work: how to create a situation. Not just an event, but an actual situation. I ended up sleeping and camping in some of my work. At the Whitstable Biennial in 2008, I spent ten days living and sleeping with guests in a deserted fishermen's hut. The heightened sense of art and life merging into a situation is still part of my work.

AK: Let's talk about Marcus Fisher, your Orthodox Jewish male alterego who has appeared in many of your projects. I remember so clearly the first time I encountered him in your work, sitting gob smacked in a university lecture hall looking at a huge, projected, unforgettable portrait of Marcus Fisher.

OA: Oh, yes. Marcus Fisher.

AK: Who is he?

OA: Marcus Fisher is influenced by one of my closest friends in Israel, a male teenage friend. When I left Israel we were both in the army. I managed to leave through marriage but he couldn't. He tried to get out of the army by not eating and starving himself, but it didn't work out.

After I got to England, 'Marcus Fisher' sent me a letter. He was still in the army. The letter said that he wanted to put me to a 'friends trial'. In Israel this is a term: it's when your friends put you on trial. Basically your community's saying that you're guilty of something and in my case, I was guilty of leaving the country and leaving my friend called Amir behind because he could not get out of the army and I could, and on top of that I left Israel, so I deserted him. You can see the intensity of the friendship. He told me he was going to create a court case against me. I've been obsessed with trial cases since.

Gradually, over the years, Amir became Jewish Orthodox, so every time I visited I saw him less and less. In the end, he couldn't see me on my own because I was a woman and in the end he couldn't see me at all. So Marcus Fisher is a character based on that friendship. I dressed up to connect with him because I've lost the friendship. I didn't think about it as art at all. I literally thought about it as a homage to a friend. I just started walking outside dressed up.

AK: In London?

OA: Not just in London. For a long time it was just my life and what I did as a young person. Then I actually realized that these things have names: 'performances, interventions, one-to-one performances', or whatever they're called.

AK: How many years was this?

OA: I did it for a long time: six or seven years. I did a lot of different things: one-to-one encounters, interventions, photographs, and videos. I was both very private and very public. I stopped when I felt it was taking over. I felt like I was accessing this weird side of the family that is full-on Orthodox Jews.

AK: Do they know about your work?

OA: They don't really ask me, to be honest.

AK: How it is to work in Israel? I know you performed the amazing and risky Dancing with Men (2003) there.

OA: Dancing with Men was totally unregulated. I heard that there is a yearly Jewish religious festival at the North of Israel celebrating the death of Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, who said upon his death: 'don't mourn me, be happy, dance, smile.' So there is a lot of dancing and celebrating on the mountain. But only the men dance: the women wail and mourn. So I dressed up as a young orthodox Jewish man (no beard, nothing that can be pulled out) and went and danced with them. There were two dance areas: one for the Ashkenazi dancing, like a long snake that turns and bends made of everyone holding hands, and one for Safardic dancing, which is made of biblical sentences sampled into techno and the dancing looks like being in a techno club. I joined the Ashkenazi dance, and made sure to hold hands with an orthodox teenager, so we were both short and my small hand would feel normal to him. It is a huge outdoor environment; around 300,000 people participate, like outdoor raves in the 1990s.

Another performance I did in Israel was in 2006. It was in my old room in my parents' house, where I inhabited the room and spoke to visitors at the Herzeliya museum through Skype. At times, my parents joined in. The point was to create time gaps: my room has stayed the same since I left in 1987, so that was important to me and when I spoke to visitors, they thought it was a video until I said something like – you with the red jumper, then they've realized the image was being streamed in real time.

AK: Why do you think that, over the years, you have moved from small scale and discreet interventions to working with large groups of people in bigger productions?

OA: I became interested in not performing myself in 2011 after Hairoism, which was a six-hour performance where I turn into different male public figures from the region, including Ringo Starr, through different hairstyles. Israel refused the Beatles in the 1960s claiming that the band would corrupt the minds of young Israelis, and few years ago Starr refused to visit Israel's 6--year anniversary celebrations due to his support for the Palestinian cause. The reason he is included is that his widow's peak and hairy neck are shared with Yassar Arafat. At the end of the performance, I am naked and the public covers me in hair so that I become a hairy monster.

In Hairoism, for six hours I don't do anything, I'm passive, motionless and silent. I absorb six hours of toxic videos of Dayan and Liberman and all these other militant male figures and the audience's hair is stuck on me: the public were donating strands of their hair, or shaved it all together, in situ. It is an abject and toxic performance turning into all these male figures such as Avigdor Lieberman and Moussa Abu Marzouk. After the last performance in Brussles in 2011, it became clear that I didn't want to be performing with my body anymore. I felt exposed. I also felt that if it's all about me, it limits the reading of the work a lot.

AK: But your work is still very interactive.

OA: Well, in retrospect I realized that actually doing work when you're not in the work is just as exposing and people read you into it, in just the same way as if you were performing yourself.

With Party for Freedom, for example, I thought that I was moving away from myself but actually it was extremely exposing, since I dealt so much with the political unconscious. That was interesting to realize: it's what you put in your work that makes you feel exposed.

I also think that this move from solo work to collaborative projects relates to the fact that I started to believe in the idea of bigger communities, rather than just one-to-one encounters.

AK: This also relates to a change in how you work with institutions. You travelled around for years performing.

OA: Yes, I was with my suitcase just travelling all the time. I was going through airports with the whole Marcus Fisher attire in a box like the fake dildos and the locks and the hat and always in airports I would be asked, 'Are you a magician? What do you do? What is this stuff in the box?' It was always so funny in the airports. I think for one performance in Canada – Open Surgery, not Marcus Fisher – I travelled with 80 kilograms.

AK: So what changed?

OA: The kind of institutions that use to show mid-production scale performance just don't exist any more since the 2008 financial crisis, or they've changed their programing. I use to travel nonstop performing and I made my living mainly this way. This became impossible as the performance landscape changed. Now, it seems to me that there is either money for big productions by established companies, or for small low-paid individual artists 'come-with-your laptop' style performances. Medium-scale performances have somehow been less and less programed. I think that's also why, since the financial crisis, I have moved to making larger work. My solution to the crisis was to go big and it seemed to work for my practice and its sustainability.

These days, I'm also more interested now to spend a lot more time with projects. In the past, sometimes I'd wake up in the morning and have an idea and go outside and do it, like shoot a video in one day. Now, projects take two to three years to complete. That's another big difference. The project I'm working on now, for instance, is called 'Revisiting Genesis'. It's really different. I'm totally obsessed with it. It's a web series.

AK: How many episodes does it have?

OA: Ten. For the first season anyway. It's about a nurse who makes slideshows for people who are about to die. She gets a phone call from a woman called Genesis and then her friends ask her to help find her somehow. Though the nurse usually only works with dying people, she agrees. So every episode is an unfolding of the slideshow of who Genesis is, and this attempt at trying to bring her back.

What unfolds through the slideshow are partly photographs I've taken in the late 80s and 90s in post-industrial England, as well as images of minorities. One of the things that comes out of this narrative is that it's not that Genesis is disappearing, it's that all the structures around us are disappearing. That's part of it. There are also slideshows for those who are really facing death. It also turns out that she's a reincarnation of a few women artists who died because women are partly invisible in the art world or they're kind of semi-visible. That's why 'Genesis' is semi-visible. That's the project. I'm looking a lot at how we organize ourselves when a friend is ill or dying, looking at death, palliative care, and post-death.

AK: Digital afterlives.

OA: Yes, I am totally obsessed with researching the digital afterlife. The experience of my brother's death was the initial influence.

AK: When was that?

OA: Seven years ago. It took me that long to start looking at death after he was gone. Also, last year, quite a lot of of artists I knew died. Ian White died, Alxis Hunter died, Monica Ross died, Rose Fincasley, and José Esteban Muñoz. I am thinking about what they left behind and how we deal with it.

We live in this kind of easy, urban life and death is not part of it. It is more of a taboo. I've been speaking to doctors and nurses about palliative care, the taboos around death and ways of dying. I realized that the dying is the most ignored minorities of all. My studio has ten columns on all the walls, each representing an episode. In Episode 9, people of Kingston will be involved as live participants in the shoot in a party scene dedicated to utopic communities. With every episode, we see an increase in the number of friends supporting Genesis. It is like a growing community of support: a heterotopic space.

Watch Oreet Ashery's Semitic Score, commissioned especially for Ibraaz projects, here. The work was a performance that was initially conceived for 2Fik; a score of 12 instructions, each one-minute long. The instructions were something like: '...walk, crawl, beat yourself up, defend/attack, spit in the hole, dance for me, Free Palestine, swear, find it, suck…'

Oreet Ashery is a visual artist based in London. Ashery's work engages with biopolitics through an interdisciplinary practice spanning live situations and performances, artefacts, video, photography and writing. In her earlier work Ashery embodied a variety of male characters, questioning gender materiality while exploring issues of power, agency and cultural autonomy. Ashery's work is shown in an international context including domestic and public site-specific locations, museums, galleries, biennials and festivals. Most recently Ashery produced Party for Freedom, an Artangel commission in 2013-4 and The World is Flooding, a Tate Modern Turbine Hall commission, 2014. Ashery's work has been discussed in various publications in numerous languages, she is currently a Fine Art Fellow at Stanley Picker Gallery and a Visiting Professor at the Painting Department at the Royal College of Art.