Interviews

Not New Now

Reem Fadda in conversation with Fawz Kabra

The sixth Marrakech Biennale, curated by Reem Fadda, art historian and associate curator at the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi Project together with Ilaria Conti, assistant curator of the exhibition, opened on February 24, 2016. Titled, Not New Now, the exhibition features forty-five artists whose practices range from performance, painting, photography, sculpture, installation, and action. With this exhibition and the particular title of Not New Now, Fadda approaches the term 'contemporary art' critically, opting instead for the notion of 'living art', which, as she explained during the opening, 'comprises art that is now; about the living, as in to live, the rights of people, society, and politics. It harnesses the contemporary that is essential to the present day. It is active.'

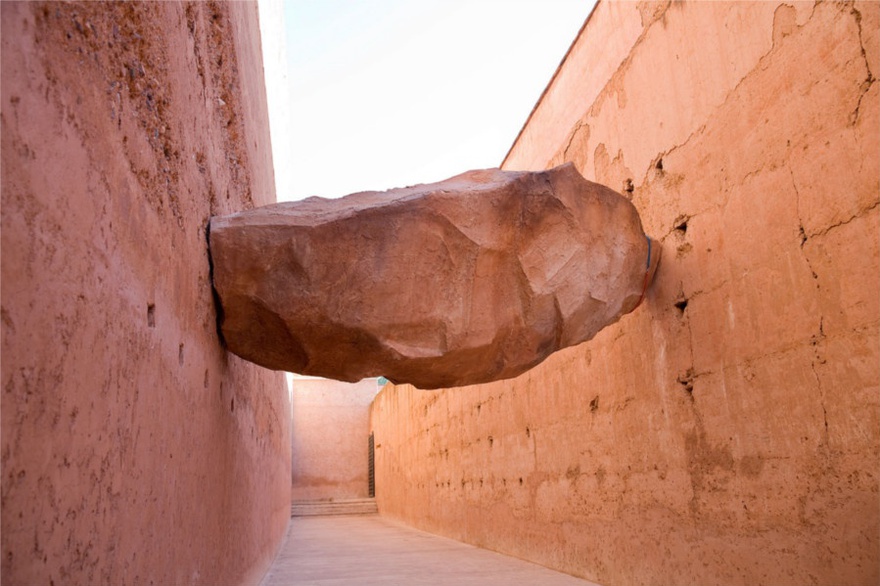

Using Marrakech as both site and space, the works inhabit the city's arteries and become part of Palais Bahia, Palais Badii, Dar Si Saïd, and Pavilion de la Ménara, the main exhibition sites that expend Fadda's curatorial methodology, which thinks through decolonization as an un-coding and a re-composition of aesthetic syntax, interrogating modernist utopia, retying disrupted histories, invoking cultural resistance, and capturing heterogeneous and plural narratives within particular transnational histories. Several threads run among the works, including issues of sovereignty, power, aesthetic belonging, property, natural resources, labor, and capital.

Fadda's conception recalls the work of art theoretician Suhail Malik, who has lectured on art's exit from Contemporary Art. In these talks, he questions how to work outside of the conventional custom of Contemporary Art's institutional activity and self-reflexive logic, and how to successfully utilize art. Free from its requirement of non-utility, we can get out of the expectations that art should be non-instrumental, liberating it from this locked-in logic. Not New Now presents a reshuffling of conventional value systems and hierarchies, as objects, actions, and the socio-political are together presented in this exhibition. Not only does Not New Now come at a time when the world seems to still be plunging deeper into political and social turmoil but it also approaches contemporary art critically, finding in the art of today valuable social responsibility.

Fadda explains that she lived in Marrakech, traveling throughout the city but also the country, learning from the place, its history, and its people. The curatorial text explains, "Marrakech is Africa and the Arab world," making it clear that the Marrakech Biennale is a response to the energy of the city and the history of its artists. With this, Fadda has conceived of a site-specific exhibition, using Marrakech and its multiple locations as the framework, to put together this timely exhibition, which not onlyasks that we rethink the term contemporary but also attempts to set in motion a curatorial concept that is in service of the regional location, and the artworks and the histories they invoke, reinstating art's agency to reframe ideas and be a site for action, now.

I had the opportunity to interview Fadda, who is also a colleague, and discuss MB6 as well as her curatorial approach and thinking towards contemporary art biennales, histories of decolonization, tying together overlooked art historical narratives from various diasporas, and of course, the art she loves the most.

Fawz Kabra: Not New Now focuses on artistic projects, research, and ideas that respond to socio-political urgencies representative of 'living art'. You use this term to explain the thesis of Not New Now and the way you see the condition behind the practice of many of the artists in the exhibition. How do you define 'living art'?

Reem Fadda: I employ the term living art as a substitute to 'contemporary art', which I feel only highlights the formal qualities in art connoting that it is within its time. However, the term living art depicts that its art in service of the living and for society, it also stresses the present day with a sense of urgency. We are living in times of emergency. The evolution of art in its employment of aesthetics and poetics in service of society and in addressing the urgent issues is important and for me is a prerequisite for art today.

FK: I think 'living art' is a compelling starting point, as I have come to view much of the art emerging from the Middle East, North Africa, and the diaspora as research based and directly responding to existing socio-political infrastructures, the environment, economy, and speculations on the/a future. In addition, Not New Now reads like a curatorial response to the state of the world. What do you imagine might be conveyed via the artworks you have brought together? And how do you perceive the state of the art world today and your role as a curator and art historian?

RF: I have tried to build an essay of an exhibition in which I tackle many ideas pertaining to my thesis and ideas on living art especially as it relates to the art of West Asia, Africa and the larger Global South. The title I chose, Not New Now was a provocation; a postulation even for myself to start to interrogate convoluted yet also tightly woven ideas.The initial idea was looking at how the concept of the new, which is a cultural trope of the modern era particularly associated with accumulation of materials and development of form, lead to excess and consumptive societies worldwide. I started to ask myself if there were instances of resistance and a counter narrative emanating from postcolonial cities and what that might be and how has that failed. In my mind there has become a corollary distinction of art produced from postcolonial legacies and that produced in the West, where the latter is consumed with formalism, the former subjugated nations have used the vehicle of art to deal with ideas about bettering their living conditions.

The weightedness of lagging behind in terms of material development was compensated with years of thinking content and ideas about living conditions. I divided my exhibition in chapters, like an essay, but in various locations and I explored ideas that range from investigating eras of decolonization, to recycling matter, thinking about preservation of matter versus lives, conditions of labor, redistribution of wealth and hierarchies, politics of gender and queerness, and resistance through the production of knowledge. The most important aspect for me in the above was to stay loyal to the artists and their works; ultimately they are looking at ways to better our living conditions through criticality, poetics, politics and the aesthetic and I wanted to demonstrate that. I navigated the above, as an art historian but ultimately I succumbed to my inner artist and let intuition navigate the choices and eclecticism you experience in the show that narrate the way I view the world – with a lot of positivity!

FK: Drawing on lateral connections in between works by artists from different global sites: Africa and the Middle East, the Mediterranean, South America and their diasporas, including artists from entirely different generations and historical contexts, your show highlights a cyclical ecology in art practices and a layered logic. Can you speak to the ideas of bringing together some of these artists where previously their connections were not apparent? For example, the works of African American artists such as Al Loving, Melvin Edwards, and Sam Gilliam presented at Palais Bahia alongside the Casablanca Group of artists such as Farid Belkahia, Mohamed Chabaâ, and Mohammed Melehi who together taught at the Casablanca School of Fine Arts.

RF: It was important for me to focus on Morocco and Africa in this biennale and to explicitly highlight lines of solidarity worldwide. Linking the African continent to its diaspora is necessary. There is an essentialism that comes with place. The diaspora becomes unanchored, uprooted or in limbo because they are not in 'their' place. So if the summary of the thesis of this show was to say 'lives matter' then place, materials, surroundings, all become transitory and circumstantial. Also, I started to conflate the state of refugees with their ultimate diaspora. I have experienced the prejudice associated to being of the diaspora in the US but also in Palestine. Instances where peoples essentialist understanding of race or belonging have been questioned, meaning you are less a Palestinian because you do not live in the West Bank or you are 'a watered down half-breed African' because you are also Arab from North Africa, and so on, and the likes of these accusations. This is not about purity or ethnicity. This is ultimately about solidarity and if anything, diversity. I believe that in this turbulent world, solidarity, action, collectivity and empowerment are the essentials. In that way of thinking, and with the flux and generations of refugees, Europe is extended and becomes African, too.

There are multiple generations of artists, particularly from Africa, that have engaged with questions associated to people and society and ultimately avoid essentialisms. The Casablanca School of artists in Morocco did just that; its key proponents like Farid Belkahia, Mohammed Chabaâ and Mohammed Melehi advocated for progressive political and social ideas through rethinking the very medium, shape and form of painting in the early 60s during a time of identity shaping after Morocco had gained independence. They helped imagine a language of painting that was speaking in a colorful graphic way directly to people, either by using materials such as henna, copper and leather or signage that is linked to these various communities. I argue that their ideas persist in the psyche of their societies because their visual iconographic paintings became emblems across 40 years that were capable of shaping this progress and non-essentialist discourse. And of course this was in addition to their actions and writings of manifestos and journals all that was able to carry this influence as well.

Simultaneously, there is the contingency of African-American artists, such as Al Loving, Sam Gilliam, David Hammons, Melvin Edwards, who by the way had travelled Africa extensively and even shown with Melehi in the 80s, and these artists were really trying to formulate a practice of their own as avant-gardes, many speaking also to subject matter related to the civil rights movements, which they were actively participating or witnessing at its time and continue to propagate ideas for liberation and equal rights. Additionally I wanted to root and cross-pollinate the practice of younger generations of artists with this marginalized yet important history.

FK: The centres for the art world have changed and become many. Places like Beirut, Cairo, the UAE, and beyond that Jakarta and Krakow, are generating different art worlds. Europe's colonial history in the region resurfaces in artwork time and time again. We are redefining the 'Middle East' and have even employed the term West Asia to propose a new and decolonized way of seeing the region. The map is being redrawn once again and migration (rooted in these colonial histories) has become a global issue. In this context, it does indeed feel urgent to redefine the art of the moment and reclaim agency for art and cultural production and discourse in these complex and historically rich regions. I think it is time to discuss how the art of today is actively presenting society as it is now. What is your approach to this?

RF: The thesis of the main exhibition of the biennale is anchored on two concepts, decolonization and cultural reappropriation. Both concepts are mainly championed and embodied by artists who have influenced me greatly and I have naturally included in the biennale. Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti have been working under the collective Decolonizing Architecture for quite some time, practically using and implementing methodologies of decolonization in the context of Palestine applying it to various fields; education, culture, architecture etc. They have insisted on creating structures and environments that permeate self-determination and knowledge making. In my vocabulary, this successful methodology should be applied everywhere especially in art. Decolonization as a methodology for resistance has a long history and legacy especially across the African continent and unfortunately much of that history has been relegated to failure in the creation of democratic independent nations. This is something I also wanted to question. Many artists in the biennale address decolonization both critically and as a methodology, such as Manthia Diawara, Otolith Group, Eric van Hove, Isak Berbic, Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti, and so on.

As for the term cultural reappropriation, it was coined by artist Kader Attia and it advocates for contending with culture in non-hegemonic terms and in a cyclical fashion. It draws attention to the aspect of learning and borrowing from cultures. The colonizer learns from the colonized and vice versa. It is important in this framework to accept the diversity of ideas and non-hierarchical structure that culture really is about. This of course is a solution to current power systems that enslave culture to subjugate others in service of maintaining and furthering their dominance. Many artists in the biennale intrinsically worked in this line of thinking, redistributing the wealth of materials ideas and attributes of culture onto others, Superflex, Talal Afifi, Adrian Villar Rojas, Oscar Murillo, Haig Aivazian, Jumana Manna, Saba Innab and, of course, Kader Attia.

FK: When it comes to public space, how did you experience Marrakech and the Medina as a platform for engaging contemporary art? These sites, being already well-established places of congregation, gather various publics on a daily basis and the artworks will inhabit these places momentarily. How do you see these uses intertwining?

RF: As soon as I set foot in Marrakech I realized that the 'challenge' facing me was that I had no traditional white rooms or museums to work with and exhibit the art. That also came as a great relief for me. It was like going back to my early days working with art in Palestine where that infrastructure is also nascent. Inhabiting lived spaces became the solution. The previous edition had worked with several heritage sites and I just continued in that vein. It also helped push the concept of the biennale, in the questioning of tropes such as newness to another degree. These heritage sites are largely spaces that are visited by various publics, tourists, students, locals; many are regarded as public parks and yes, sites of congregation. I think that's one of the intuitive leads that pushed this exhibition to focus on ideas pertaining to people.

FK: Can you tell me about the title Not New Now? What are the politics of 'Now'?

RF: The title consolidates a lot of time concepts. It is quite complex but also rather simple. I want to focus on the present. Not the past or the future. I also want a time concept of the present that relates to the living, to people. I have strategically opted to utilize the term living art versus contemporary art because I would rather allude to a present tense that is connected to the living or values lives and society. This active sense within a participatory art practice is more attuned to my interpretation of how art should be especially in times of crisis and urgency like the ones we are witnessing today. It's definitely a call for responsibility and solidarity in art geared at how we reimagine our lives.

FK: Building on this, how do you think we can do away with ill-defined categories such as 'contemporary' or 'post'-this or that?

RF: I am not sure I would call these terms ill-defined. I think they are precisely well-defined because they evoke the senses of what they encapsulate from the regions they depict. However, I think there so-called global generalized application is what needs to be reconsidered. I also think it's necessary for various other regions to take a decolonizing approach and self-define and categorize themselves. Provide nuanced readings from their own perspectives.

FK: Is living art specific to the site of Marrakech or do you think contemporary art can still be a fitting term beyond MB6, today? If not, how would you redefine this moment?

RF: I do think living art is specific to Marrakech, but can also be applied to art that anchors itself on ideas of decolonization, the postcolonial and resistance methodologies. I did not suggest the employment of the term to replace one hegemony over another. I think there are various terms that need to co-exist. The term also served my own personal exhibition development and prognosis and that's the extent of where it stands for me.

FK: I found your approach to the Biennale catalogue a bold statement in itself. Anyone can build their own catalogue by simply visiting the various sites and artworks, collecting individual artist's catalogues, to build a larger Biennale catalogue. This method continues to expand on the ideas of communicating directly with the various audiences, making art and its discourse accessible to all. Can you talk about your approach to democratizing the catalogue?

RF: One of the core ideas of the exhibition was examining the importance of the production of knowledge as a symbolic means of resistance. We thought of a way where we could disseminate the information and make the information and catalogue available for all. We were also trying to be cost and work effective and efficient. We created a formatted booklet where the artist would input their process and images related to their work, so the editorial work was shared. The curatorial team then wrote the texts that were subsequently provided into three languages Arabic, English and French as the backlog and write up on the work. These 8-page booklets on each artist were then placed near every artwork and the viewer would collect them and that would make out the exhibition catalogue. Also all PDFs of these booklets are currently online on the website of the biennale and are all downloadable for free. It's an A5 format so it is easy to print and reproduce at home.

FK: Having now curated and organized the Marrakech Biennale 6 and previously curated the UAE Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2013, how have these experiences changed your understanding on the function of such cultural production and the institution of the Biennale?

RF: These experiences are extremely important in the wide reach that they could achieve. Biennales insert themselves in the very fabric of cities. They allow a far-reaching audience to encounter art, sometimes even coincidentally, like the many tourists that are unaware of biennales while visiting the cities and also see art. We should not underestimate how important these encounters are. They change psyches and alter stereotypes, especially in the context of Marrakech or the Arab world, as places for the production of culture and art. And many of these biennales have a great educational program anchored to them. I have personally done numerous tours with young students, teachers and college guides here in Morocco. You can immediately sense the enthusiasm and benefit of such visits. We are hoping to have reached over 120,000 visitors for the Marrakech biennale by the end of it and conducted educational tours for nearly 3000 students from Marrakech and its surrounding townships and villages.

FK: During your public talk about MB6 you mentioned that people who know you know that you love painting. I am curious, what kind of art excites you?

RF: The art that excites me is tough art. Art with a tough skin that makes you ponder the world around you in awe. Art that you can feel simultaneously in your mind and in your gut. It creates a euphoric sublime experience of awareness of things around us. I really appreciate intellectual art and artists. They are the people that can draw the new frontiers of thought through the making of poetic things.

FK: What is the first artwork you remember?

RF: The first artworks I remember are those of Ismail Shammout's. It was my first ever exhibition. I think I was barely five or six at the time. The way he dedicated his painting to recording and showing the plight of Palestinians continues to stay with me.