Interviews

What Was Lost

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige in conversation with Nat Muller

In the early 1960s, a group of students led by the professor of mathematics and physics at the Haigazian Armenian University in Lebanon, one Manoug Manougian, designed and launched rockets for the purpose of exploring and studying space. The project was called the Lebanese Rocket Society and was halted in 1967, an ominous date in the history of the Middle East and the world as a whole. The project has remained largely forgotten since. Over the past few years, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige have used this project to trace a submerged history of rocket propulsion technology, the idealism of space exploration in the Middle East, and the connotations of rockets in the aftermath of the Six Day War between Israel and Arab Sates in 1967. The expiration of the Lebanese Rocket Society, coinciding as it did with the Six Day War, heralded an end to a number of things, not least the Pan-Arab ideal and the hopefulness once associated with space exploration. Were the two events linked – the technology of space exploration exchanged for the ordnance of militarism – or did they augur a more profound disillusionment that stills hangs over the ideal of revolutionary thought and idealism today?

The archives of the Lebanese Rocket Society, when made available to Hadjithomas and Joreige, also gave rise to other elided narratives that bring together a serendipitous but unlikely connection between space exploration, carpet weaving in Lebanon, the Armenian Genocide (1915–1923), a gift to President Calvin Coolidge in 1926, philately, a veritable mountain of red-tape, and a tribute from the artists to those involved in the Society. What we witness in Hadjithomas and Joreige's ongoing project, which goes under the collective title The Lebanese Rocket Society, is the re-emergence of the ghosts of the present: the narratives, tales, travails, tributes, disenchantments, desires and hopes that refuse to remain either lost or forgotten and, if given time and space to re-emerge, effectively reconfigure how we think about the exigencies of the present in relation to the all too easily forgotten idealism of our pasts.

Anthony Downey

Nat Muller: I want to talk about your solo show at The Third Line, based on the so-called Lebanese Rocket Society. Can you contextualize and relate it to the project you did last year in Sharjah for the biennial, which also looked at the origins, proceedings and eventual dissolution of the Society?

Joanna Hadjithomas: The Lebanese Rocket Society is a space project, begun in 1960 in the Haigazian Armenian University in Beirut and it was led by a maths and physics professor called Manoug Manougian. He was working at the Haigazian University in Lebanon and with the help of his students and the Lebanese Army, launched rockets for the purpose of exploring space. They launched the first rocket of the Arab world. It was a serious scientific project and they launched several rockets which became bigger and bigger over time. The Lebanese government, who helped at the outset, even made a stamp in 1964 to commemorate these events. What was very strange for us is that the entire project ceased in 1967 and today remains a project that is totally forgotten.

NM: Was it archived?

Khalil Joreige: At the beginning of the project, we searched in Lebanon and realized that there was very little by way of an archive and a more or less complete lack of images. We made part of the documentary and installations on this lack of images. But then we managed to find a lot of images.

JH: The project began with researching a feature documentary film – little by little, we went to meet people who were part of this experience and one of them, Manoug Manougian, the professor I was talking about, had everything: all the images, all the films, absolutely everything. An individual had kept it all but thousands of kilometres away from Beirut. Suddenly, we had all of this incredible material. We were also very interested in the years when this project was taking place: it was the 1960s, the peak of pan-Arabism and the moment for revolutionary ideas – or at least that is how we imagined it.

KJ: The work of the Lebanese Rocket Society allowed us to think about the possibility of it intervening into our present and the conditions of our present. What struck us is that this space project was for a scientific purpose, not for targeting any enemy or indeed for warfare in general.

NM: Was it funded by the military?

KJ: It was helped by the military, but it had no immediate military aim to begin with – this is possibly one of the reasons why it was stopped: it had no clear military ambition and was really a scientific project for Manoug and his students. The army had others intentions. What interested us was this capacity of these people for dreaming and projecting themselves to make their dreams possible. It captured the mood of the 1960s. When we did our research, we realized that the development of rocket technology was a relatively new invention and that the conquest of space was in the news almost every day.

NM: Is this also about a re-appropriation of history that has been forgotten, a sense of a time that has since passed?

JH: This is not a nostalgic project. We work with history and with archives but it is very important to re-enact this process in the present. So we decided, because it was a forgotten project, to produce a sculpture of one of the most important rockets at the time, the Cedar IV. We built this 8 metre rocket in Beirut to the exact same dimensions and shape of the previous one, and decided to offer it to the Haigazian University where all this started. And it became part of the feature film we're making too. What was interesting is that the rocket was initially completed in Haigazian University and then taken to Dbayeh where it was launched towards the sea. By coincidence, we built this rocket in a factory in Dbayeh, so we thought we had to bring this rocket back from Dbayeh to Haigazian and also move this rocket – which looked a lot like a missile – through the streets of Beirut. To do so, however, involved a number of complex processes and negotiations. It was very important that this rocket – if we put it in the university or in an art space like Sharjah – was not seen as a missile, but as the culmination of a dream produced by researchers and people like Manoug Manougian.

KJ: There are many misunderstandings in our region and this is an important aspect of this work – it is a way to re-intervene in our territory and rethink the relationship of the past to the present, the projects that were started and abandoned, the idealism and ambitions inherent within them, and how we look at that idealism today.

NM: What's interesting in this project is the focus on the object of the rocket in and of itself. When you place it in Haigazian University, it has a different context; when you place it in Sharjah as part of the 2010 Biennial there it also has a different meaning – how does the sensibility of the object change in that respect?

KJ: We need to be clear here: the recreation of the rocket in the form of a monument – which is a reconstitution of the object – creates no misunderstandings as such. What does change is the connotations surrounding the object of a rocket today. When you see such a thing today you are wary of its connotations.

NM: The rocket has become a symbol of war whereas it was once a symbol of idealism and exploration.

KJ: That means that the significance, the meaning, is shrinking, becoming much narrower, so we have to extend the possible meanings of the object to make meaning larger, so to speak, and to bring something else to bear on the discussion. The object of the rocket is placed in the two territories of art and science, where you are protecting such meanings and the potential meanings that could unfold in the future.

NM: This is also somehow a recognition of a modernity that has been forgotten when we speak of the 'imaginary' in this region?

JH: I spoke a lot with Khalil about this notion of modernity – I don't think that we are any more modern today than, say, back then. I think we had a different perception of ourselves. And those perceptions changed a lot after the defeat of 1967 – the war between Arab states and Israel – and for many people of our parents' generation this was a traumatic moment in which we inherited a moment of disenchantment. We saw that Pan-Arabism and the Pan-Arabic dream faded. So I think it's a moment where perceptions changed. When we produced this project, it was because we really needed something that was positive and about big dreamers. We wanted to make this rocket as a way of reconnecting to these dreams and the idealism associated with it. So, of course, the notion of modernity has a part to play in this discussion.

KJ: For us, it's much more about the notion of the contemporary which is in turn linked to this ideal of territory. Territory is always defined as a geographic place, but for us it can also be a time in space. The contemporary of someone who is in another country, for example, is a time we are sharing in space rather than place. Things changed after the defeat of 1967, the rhetoric became less about hope and revolution and more insular; the Arab world turned inwards and away from revolution. There are repercussions of this all around us and rather than become cynical or accept the legacy of this we are fighting for the production of meaning in this project, for a territory where we can still exist and rethink the past and what we are today because of it. It is a way to rethink the notion of monument, which is central in our work. The sculpture itself questions that, inasmuch as its full title is: Cedar IV, Element for a Monument (2011).

NM: So, it's really about placing agency as a central force in a critical practice?

KJ: When you are using a word like agency, it can be frightening, because we are not in a position of power.

NM: You don't have to be using agency from a place of power.

KJ: Agency is a powerful thing, yes, but it is other strategies that interest us.

JH: We always work on strategies inherent in images and how they are produced. Our work is of course very linked to the region but it has more to do with the medium we are using, we always reflect on what we use, photography, film, video, it's always part of how we work.

NM: This discussion of medium is interesting because in Sharjah, during the Biennial last year, you had the rocket placed in the square and then you had these amazing 8 metre photographs of the full images that were folded accordion-like and placed in a fragmented way next to each other. How does the exhibition at the Third Line gallery follow up on that?

JH: For us, the project as a whole consists of a film and five installations that we are making and the rocket as an object is part of that. The photographic installation you're talking about is called 'The President's Album'. It is a photo installation consisting of 32 identical photographs, 8 metres long each, folded into 32 parts. Each photograph is presented through a different fold and as a whole the installation displays the entirety of the image in 32 separate segments. Each segment or fold is a composition of two images: the first is an image taken from the 32-page Lebanese Rocket Society photo album that documented the Cedar IV Rocket's launch and that was offered to the then President of Lebanon, Fouad Chehab. The second is a part of an image of the Cedar IV Rocket's reproduction, our 'rocket' so to speak, installed at Haigazian University, but painted as it was in reality complete with the Lebanese flag depicted on it.

KJ: In each part lies the reminder that although each apparent fold represents only a small fragment of the rocket, the whole image and history is potentially there, but hidden. The installation of 'The President's Album' questions the image, its fragmentation, reconstitution and recognition; it posits forgotten histories such as hidden folds that need only to be unfolded so as to re-emerge.

NM: And you also produced a Golden Record and a film of it alongside the actual object.

JH: Yes, we produced a new Golden Record which was a tribute to the recordings that were sent on Voyager I and II when they were launched in 1977. The original Golden Records were intended to portray the diversity of life on Earth and were to be sent to a potential extra-terrestrial presence. We thought it was important to produce a new one, not to create a new phase to the story, but to produce a Lebanese one with the sounds of the country on it alongside others.

KJ: Usually, you can reconstitute an image but the reconstitution of the sound of the 1960s is much more complicated, because the backgrounds change – you have sounds of air conditioning for example and other kinds of sounds. Even the tools for the recording changed. We went back to some of the original sounds and we made a kind of edit along with newer sounds, trying to present an homage to the original Golden Records that were sent in the 1970s. Carl Sagan, who was in charge of this at Cornell University, also had to imagine somebody in the future who cannot understand language as such and how he can then represent life on Earth to this imaginary person from the future who comes across the Golden Record. So, as with our rocket, there is a degree of idealism if not hope to this project.

JH: We are very open to accident and encounter in our work, so when we were searching for details on the Lebanese Rocket Society, we read that while sending the original rockets, and in order to follow them in space, a signal that was 'Long Live Lebanon' was put in the head of the rocket and broadcast via radio. So this connected with the story of the Golden Records, with people sending the sounds of Earth, like messages of peace and music, into space and perhaps even to eventual aliens – although we have yet to hear back on that one. We thought that if we had to choose the sounds of today, the sounds of Earth and of our region, what would those sounds be?

NM: What were the sounds?

JH: We first made a 20-minute piece as a tribute to the original Golden Records, complete with sounds of the sea and wind and nature and adding new sounds that have a relation to the region and a link to revolutions and science at that period of time. We then filmed the Golden Record spinning with its sounds audible.

KJ: And a message to aliens in four languages, French, Arabic, Armenian, and English.

JH: Because this piece is also about the 1960s, there are sounds from that period. There is a space feed, for example, and also a ballad from 1960s Beirut.

KJ: It's also a testimony to the memories of the Lebanese Rocket Society; through what they told us and the conversation we had we managed to record some of the sounds mentioned.

NM: Tell me about the carpet included in The Third Line show.

JH: The carpet is another story and happened through another encounter. We were searching for details of the Lebanese Rocket Society and we were told a story by our friend Missak Kelechian that moved us a lot. It was about these orphan girls who had come to Beirut after the Armenian genocide (1915–1923). They were between 14 and 16 years old, so they were not little girls anymore but couldn't be left on their own, so they had to find something to do. An American organization, Near East Relief, was helping the refugees at the time with donations from Americans who gave money to this organization by not eating once a year – this rule was called the Golden Rule – and this money helped to build the carpet industry in Beirut, in a mountain town called Ghazir, about 40 miles north of Beirut.

KJ: There were 3,200 orphan girls working there and they decided in 1925 to offer a carpet as a sign of gratitude to the White House and the American people. Four hundred girls produced one that was 5.5 by 2.8 metres in width, or about 18 by 12 feet. It was given as a gift to President Calvin Coolidge in 1926 and is still housed in the White House, but is not on show anymore – it's currently in storage, maybe for political reasons. On the back of the carpet there is a note recording the fact that it was made by the Armenian orphan girls in the Near East as a sign of gratitude. Amongst the girls who helped produce the carpet where women who would become the mothers of individuals who would then later become students of the Haigazian Armenian University and members of the Lebanese Rocket Society.

KJ: It started as the Haigazian Rocket Society and then became the Lebanese Rocket Society as a sign of gratitude to the Lebanese.

NM: So it's something that comes from a small Armenian community and then, through a sign of gratitude, becomes something of national pride.

JH: Yes, and that was when the stamp was made in 1964.

NM: And were these used as proper stamps?

JH: Yes, it was a real national stamp and suddenly we thought that the Lebanese Rocket Society included people who were the descendants of orphaned Armenian girls and we wanted to make something to re-enact this and be a part of a sign of gratitude to them, both the Society and the girls who made the original carpet for Calvin Coolidge. So we decided to make a carpet with the stamp.

NM: And you had the carpet made in Armenia.

JH: Yes, we had it made in Armenia. They made it by hand because it was very important to continue the traditional means of producing carpets.

NM: Can you maybe talk about the photography in the exhibition?

KJ: When we transported the rockets, we were really frightened because when you look at the shape, it looks like a missile. In Lebanon, needless to say, such an object is politically very delicate. To do such a thing, you have to deal with a lot of local, regional and international powers, you need a lot of authorization, even a lot of data-mining, informing different people that this is not a weapon but a sculpture. We decided to restage it and take our time. So instead of having the whole rocket made as it now looks, we had it made out of wooden board, in exactly the same dimensions, and took exactly the same convoy, police car and soldiers through the streets.

NM: Did you also need permission to do that?

JH: Not the same permission, but we had to close the streets! When taking the photographs we wanted the rocket in the frame so, depending on the speed of the truck, we had to carefully define the shutter speed and our speed when travelling. The whole thing became incredibly complicated.

JH: The photographs, in turn, became images of a trace of a trace, images of a wooden rocket that reference a now long forgotten rocket. That makes for a very strange apparition in a city such as Beirut.

NM: On the subject of apparitions, perhaps we should move onto your project for Abraaj Capital Art Prize, A Letter Can Always Reach its Destination (2012), because that's very much about apparitions and goes beyond the Lebanese context. You have collected email spam for a decade now for this project, why?

JH: As you said, we've been collecting emails since 1999 or thereabouts. We had this intuition that these emails were saying something about the world, even saying something about the history of the world. They try to convince, through scams, that there is a way of getting money from a place, and this has to be a place where corruption is possible, where there is conflict to begin with and corruption is therefore rife. We were interested in tracing this idea in the emails because it represented a kind of 'imaginary' that was related to a colonial way of looking at places. 80 per cent of these emails are sent by Nigerians. Secondly, if you put all these emails next to each other, you have a cartography of conflicts throughout the world in the last ten years. You have them in East Africa, then they moved to Iraq and to Russia, now today, you get them from Tunisia and Egypt.

NM: So it's like a history of the world's conflict at the same time.

KJ: The tradition is quite old, dating from the sixteenth century – you also found a lot of them in the eighteenth century. At the time, it was called the 'Letter from Jerusalem'. It's exactly the same narrative structure and this allowed us to think about the notions of trust and belief and who do you trust and the imaginary that lies behind it. So we decided to embody this narration and to start to give a face to each of these emails which we already know to be a fiction.

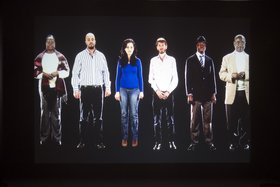

JH: You have to believe in it though, so we decided to take non-professional actors coming from the countries represented. We had thousands of emails, so in the end we chose 45, and then we tried to find non-professional actors in Beirut who came from these countries so they could read these emails. In the moment of encountering their relationship to the countries, to the stories behind the emails, something else happens, a sense of the reality behind the fictional letters, the personal cost of conflict and how it impacts on real people, not imaginary ones.

NM: Finally, a last question: you said you embody them? But they're ghost-like, so they're not fully embodied, so why that decision to not give them full presence?

KJ: It's a fiction, they are not there. But at the same time, you can believe in their presence, but it's a ghostly presence; they are there and not there. It's about immateriality, but at the same time, you want a face. We tried to turn the textual source material of selected SPAM and SCAM into visual narratives, image representation that becomes a fiction by itself. Said by these non-professional actors, the emails seem transformed into scenarios for monologues even if we don't change the texts; the stories become captivating, or even moving because they are told by a 'real' person.

JH: These texts are trash, immaterial. Usually they are sent to the trash bin, so they appear and disappear. It was important to give a sense that you can just forget about it, you can choose to skip it and put it in your trash so these people will appear and disappear in your life. So we had to find a technique that gave you this impression of absence/presence, a virtual and physical presence, a kind of a hologram.

NM: So, it's really about the encounter and the ephemerality of the moment itself.

JH: Yes, it is about an encounter. As the title says it, 'A letter can always reach its destination'. As Slavoj Zizek said, 'I don't recognize myself in it because I'm its addressee, I become its addressee the moment I recognize myself in it.' For us, all these people are like a chorus, and some of them go out and appear – relate the text and 'their' story – and then disappear again.

The Lebanese Rocket Society is a feature film documentary (92 minutes) soon to be released. Video, photographic and sound installations that compose the project will be shown at CRG Gallery, New York from 1 March.

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige collaborate as filmmakers and artists, producing cinematic and visual artworks that intertwine. They have directed documentaries such as Khiam 2000–2007 (2008) and El Film el Mafkoud (The Lost Film, 2003), and feature films including Al Bayt el Zaher (The Pink House, 1999) and A Perfect Day (2005). Their last feature film Je veux voir (I want to see), starring Catherine Deneuve and Rabih Mroué, premiered at the Cannes Film festival in 2008 and was selected as the Best Singular Film of the year by the French critics. Their films have been enthusiastically received, won many awards in international festivals and released in several countries. Together, they have created numerous photographic installations, among them: Faces, Lasting images, Distracted bullets, The circle of confusion, Don't walk, War Trophies, Landscape of Khiam, A fareway souvenir and the multifaceted project Wonder Beirut. Their work has been shown in many museums, biennials and art centres around the world, most recently at the 10th Sharjah Biennial (2011), the 11th Biennale de Lyon (2011), and 12th Istanbul Biennial (2011). They are recipients of the 2012 Abraaj Capital Art Prize. Hadjithomas and Joreige are currently completing a feature documentary on the Lebanese space programme. They are members of the board of Metropolis Cinema and co-founders of Abbout Productions together with Georges Schoucair. Joana is also a board member of the Ashkal Alwan Academy, Home Workspace.