Interviews

A Certain Aesthetic

Walid Siti in conversation with Nat Muller

Walid Siti's oeuvre draws heavily on his lived experience of exile and loss, yet at first glance that is not apparent from his abstract landscapes and geometric and architectural structures. His work is characterised by a subtle, almost understated, poetics and politics of form. It is the sub-text of repression and conflict – tempered with the human capacity for resilience in the face of adversity – that continues to drive his practice. The tension between ruin and hope, particularly poignant at this time of disquiet, directs the tone of his practice, which we discuss in this edited and abbreviated transcript from a conversation that Siti and I had in February 2017 at Zilberman Gallery Berlin, on the occasion of Siti's solo exhibition The Black Tower, which I had the pleasure of curating. Siti will be exhibiting newly commissioned work at Tamawuj, the 13th Sharjah Biennial, opening 10 March 2017.

Nat Muller: Your work has been influenced very much by your life's journey and your lived experience. You were educated at the Institute of Fine Arts in Baghdad in the 1970s and then after obtaining your degree went on to study printmaking in Ljubljana in Slovenia. More than 30 years ago, you moved to London. The geo-political differences between Ba'athist Iraq in the 1970s, Ljubljana behind the Iron Curtain and then London in the 1980s must have been stark. I was wondering if you could take us on a journey through time and speak a little bit about what it was like to study and work in these different places. How did they each influence your practice?

Walid Siti: I was born in Dohuk, a city in the Northern predominantly Kurdish part of Iraq. I joined the Institute of Fine Arts in Baghdad in 1971, so that tells you how old I am! The scene at the time was really dynamic: very competitive and energetic, and our teachers were really supportive. We would go into the alleyways, streets and parks to paint and draw. Gradually in the 1970s, as I was finishing my studies, Saddam Hussein came to power and the political situation in Iraq deteriorated. The Ba'athification across Iraq and the Arabization of the Kurdish region had accelerated. This included the wiping out of thousands of villages, and the notorious Al Anfal Campaign (1986–1989), which attacked Kurdish fighters in Northern Iraq.

I was interested in continuing my studies but was unable to do so as I was not a member of the leading Ba'ath Party. My only option, as was the case for many of my fellow students, was to go abroad and study. During that time, Iraq and the former Yugoslavia had very strong political and economical ties under the Non-Aligned Movement. So I opted to go to there; I didn't need even have a visa. Everything was new for me: the culture, the society, the language. Though difficult, it was also very motivating and exciting because it was the first time my Iraqi fellow students and I saw art in a wider spectrum: in Baghdad the references available to us were very limited. Our teachers in Iraq had studied in Europe and they brought art, theories and ideas from the modernist period to us but we were still stuck in the past; there was no real progress socially or in terms of art education. Ljubljana opened up a new window for us from an artistic perspective. We were closer to Europe and to the centre of different art movements; it enriched our understanding of art.

Meanwhile, the political situation in Iraq got worse and I hadn't been back since 1977. Because of the strong ties between Iraq and Yugoslavia, I was not able to stay there either. Baghdad pressured Yugoslavia, and the authorities hassled us; some friends of mine even disappeared and one of them was actually taken back to Baghdad by force, so I fled to London. I never thought of going to London but I had a friend there who helped me to get political asylum, so since 1984 I've been in London. London was a new stop, a new station in my life, which really opened up yet another window and opportunity to see art from different perspectives because of the art movements there, the schools, the museums and the galleries. It wasn't all rosy because I didn't know many people and being a political asylum seeker was very hard. So I worked with scraps of paper and I did what I could to survive, such as decoration work or framing jobs. But meanwhile I continued to get involved in the art scene and better times came when the interest in the Middle East and Middle Eastern art grew, not just in London but worldwide. So that gave more opportunities to exhibit and take part in different events and projects.

NM: Your biography is very much a journey of movement and one of forced movement. If we look at your recent solo exhibition The Black Tower, but also more broadly at your oeuvre, there are always ladders, staircases and towers that insinuate this movement. Can you talk us through that very important visual trope in your work? When did you start working with it and how did it develop over time?

WS: It's absolutely correct that my work somehow reflects my journey, my different stations and places in my life, and also the many borders I crossed. Of course I share this experience with many other people who – until this day – are going through the same process of crossing. So my work somehow reflects the sensibility of (im)migration, borders, militarization, the passage from one space and one society to the next, and the challenges of that very dynamic. I think the ladders are a metaphor for all of that. I use an ancient tool for climbing up and of going from one point to another; a point of elevation, where you hope to get better access, a better vantage point, or a better life. It has always been present in my work but over the years has become more abstracted, more paired down, sometimes even reduced to only a few concentrated lines.

NM: What's quite characteristic about your staircases is that they are mostly open staircases. For example, your work Passage (2016) is a close-up photograph of a cliff in the Kurdish part of Iraq on which you have drawn an open-ended white staircase. It seems to be floating, with the base and top missing.

WS: I always like to use different materials for the meaning that I would like to express. But it is also important for me to leave the end open for different interpretations, for different possibilities, other than what I had initially intended.

NM: When we look at your project sketches, it seems you are opening up certain structures there as well. In these sketches you reveal your thinking process of how your towers, ladders, installations and architectural structures are put together by showing us their visual building blocks. Most of your works seem to consist of a series of form units that you have combined together to create a whole. So this whole cycle of deconstruction and construction is going on all the time.

WS: Yes, I think it somehow reflects the experience the region I come from has been going through, at least during my lifetime. The work echoes this cycle of change you are describing in physical and structural terms: destruction, deconstruction and construction. I do like to play with different units like a game and put them back together, but most important here for me is to stress a core idea. So the lines, shapes and forms comprise the main idea of how these things are evolving and developing – but with a very open scope.

NM: What struck me when I've seen you working on a project or installing a piece is that at heart you really are a builder. You spend days putting things together with an incredible concentration and precision, painstakingly constructing and building things. There appears to be a tortured kind of pleasure involved in this whole process.

WS: Since my early childhood I've been very interested in simple readily available materials, so I'm always excited to think about what I can make from, for example, pieces of cardboard or very cheap stuff that you would get at store like Poundland. How can I transform and manipulate this throwaway and almost worthless material and make something out of it? It's kind of a thrilling challenge for me that with a bit of cutting and gluing, a bit of painting and coating with plaster, I can make something out of it. It gives me a sense of playfulness. It is this playfulness and this building that are part of the process of expectation of building and creating something and then seeing its end result. Sometimes I'm not absolutely sure where things are going but the journey is always inviting and sometimes the end result surprises me as well.

NM: As you mentioned the materials you use are cheap and easily discarded. In essence they have very little value and then you transform them in something with tremendous value of meaning. So there are all these transformations going on because of using cheap materials. An interesting example is the tiny plastic toy soldiers that we see for example in Wheel of Fortune (2016). These are of course also very much mass-produced materials. For Wheel of Fortune you have constructed a mechanised wheel of barbed wire in which the toy soldiers turn and turn, representing the on-going machinery of war. Can you talk about your use of mass-produced material and the 'mass-production of war'?

WS: I see a parallel between the mass-production of war, the dehumanization it causes, and the cheap production of mass consumer goods, like toy soldiers, barbed wire or the straw meant for brooms that I buy from IKEA and then paint to use use in my work. Human existence and individual subjectivity becomes valueless or erased. In the works I illustrate that by coating the plastic soldiers with heavy black acrylic paint mixed with plaster to remove all details and to unify their appearance.

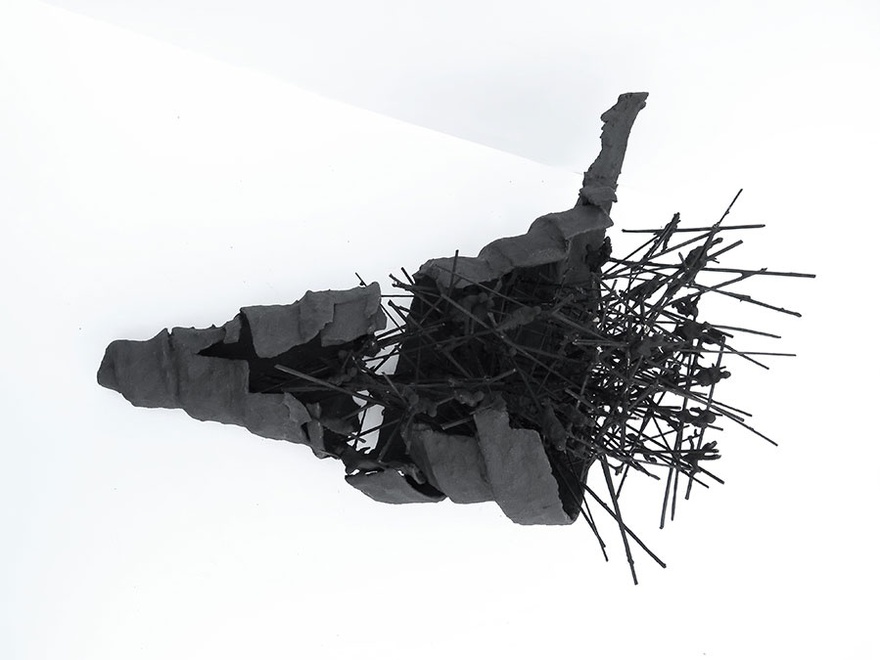

NM: It's cheap material, yet you transform them into objects of beauty; sometimes I would say even a terrible beauty, like in the small sculptures The Black Tower, Rupture and The Flag (all 2016). These sculptures – made from chewed paper, toy soldiers, glass shards and straw – are extremely fragile. They speak of of war, loss and darkness but there's still an aesthetic delight in them. Can you speak about how you navigate aesthetics/poetics and politics in your practice? You come from a region where there's a lot of conflict and ugliness and often artist from the Middle East are expected, especially by western institutions, to address whatever is happening in their countries in more direct ways. You've shied away from that. Would you say that by insisting on poetics and beauty you refuse direct representation?

WS: I never really consciously intend to make something beautiful, but of course as an artist you have a certain aesthetic. I come from a very politicized family and at a younger age I was very engaged in politics. Though I have my political views I have stopped to try to utilize my art as a political tool, even though political notions are very much present in my art. For me the poetics comes from seeing history, politics and society from different perspectives as a poet or as an artist, not as a political analyst or activist. So the poetical, or beautiful if you will, side of my art is also a kind of a salvation: a way to see the whole spectrum of what is happening in the world through the lens of my practice.

NM: To go back to your use of material; you started working with barbed wire in 2013 when you did a solo exhibition called Crossing for the Amed Art Gallery in Diyarbakir, one of the largest – predominantly Kurdish – cities in southeastern Turkey. For that show you were mostly painting barbed wire, but now you use the actual material. Can you talk a little bit about what the difference is between a painted representation and actually working with the material itself?

WS: I come from traditional schools of art in Baghdad and to an extent this was also the case in Slovenia. My education was more about drawing, printmaking and painting. Contemporary and conceptual art wasn't that widespread yet in the academies I attended. So the process of understanding, working and manipulating material developed and evolved over time. The last few years I started to be engaged in the use of new materials as an extension of my other practice in working on paper, printmaking and painting. The continuation of ideas from one material to another reveals how things are transformed through translation, moving from one reality to another. For example the use of barbed wire is a historical and contemporary symbol of control and exerting power, but is also the actual material by which it is physically being done. It serves the cruel imposition of a reality marked by confinement, exclusion, expansion, and violent confrontation: one of the many signs of the times that decorate the geo-political map of the Middle East.

NM: You've also started working more three-dimensionally and site-specifically. What excites you about working on a large scale and how do the challenges of space also challenge your artistic practice?

WS: It's interesting to work on a larger scale because of the impact an overwhelming format can have on the viewer. It facilitates engagement more easily. So that aspect has always been attractive to work with. But artistically working on a larger scale also challenges your limitations and how far you can go and stretch your understanding and manipulation of the material and mediums you're working with.

NM: What characterises your site-specific and spatial installations is your interest in architecture. This is exemplified very well in your sketches but also for example the sculpture The Black Tower (2016) that references the minaret of the Great Mosque of Samarra. In other works you echo ziggurats and other architectural structures that are part of Iraqi cultural heritage.

WS: When I started thinking of my art politically and conceptually, I was looking for different symbols and forms that could convey my ideas visually. The architecture of Mesopotamia and Iraq, and how it translated the absolute power of Saddam Hussein and other leaders was a case in point and offered interesting symbols for my visual language. From the architecture of Mesopotamia to the architecture of Saddam Hussein, who immortalised himself by building opulent palaces, huge mosques and other buildings all across Iraq, humans have always used architecture or the building of big things as a way to consolidate their power and immortalise their legacy. Whether it is the Malwiya Minaret of Samarra, the tower of Babel or the architectural motif of arches, they are all tools to stamp down your legacy on the landscape. I have also used stones and references to the Kaaba in a series of drawings called Precious Stones (2004–2008) as a metaphor for a central magnetic power that everything else is pulled to and revolves around. So the use of architecture is similar there, you are somehow attracted to it; it instils a sense of belonging to a group of society, a culture or history.

NM: Also telling is your paired down use of colour. Most of your works are black and white, dark blues and dark greys. Has that always been the case?

WS: Yes, for various reasons. When I was young I was an avid calligrapher and my background in printmaking was also influential. But from a conceptual perspective the tragedies and upheavals in Iraq just seems very black and white to me. Hardly any shades of grey or colour. So in my work this translates in a monochrome colour scheme that reflects the harshness of the conflict.

With thanks to Ilyada Guerledi for her assistance with transcribing the interview.

Walid Siti (1954, Dohuk) was present at the Venice Biennale three times, first in 2009 together with other Kurdish artists in the exhibition Planet K (Kurdistan), participating in the Iraqi Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011, and the Iranian Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015. His works can be found in numerous collections, The British Museum, The Imperial War Museum, Victoria & Albert Museum in London, The National Gallery in Amman, Barjeel Art Foundation in Sharjah, The World Bank and The Iraq Memory Foundation, both in Washington DC. He lives and works in London. http://www.walidsiti.com/