News

Conflating Histories

Two Exhibitions on the Armenian Legacy in Anatolia

Upon entering Empty Fields at SALT Galata in Istanbul, a research exhibition of archival documents and objects that explore the legacy of Armenian-German scientist Johannes 'John' Jacob Manissadjian, visitors were first greeted by an enlarged old archival photograph of what looked like destruction incarnate. In the image, broken rocks were strewn across a field in a way that was eerily reminiscent of decaying dead bodies, while a line of young poplars fenced in the apparent ruin. A path ran through the middle of the stone-littered pen, suggesting that whatever had been done was deliberate. An overlay of text on the bottom of the photo read: 'STONES CRYING OUT'. Yet these presumed bones of death were in fact the building blocks of a natural science museum in Merzifon, Turkey, a town in northeastern Anatolia. The photograph was used as a way to raise funds for the museum that was later built on the depicted site in 1911.

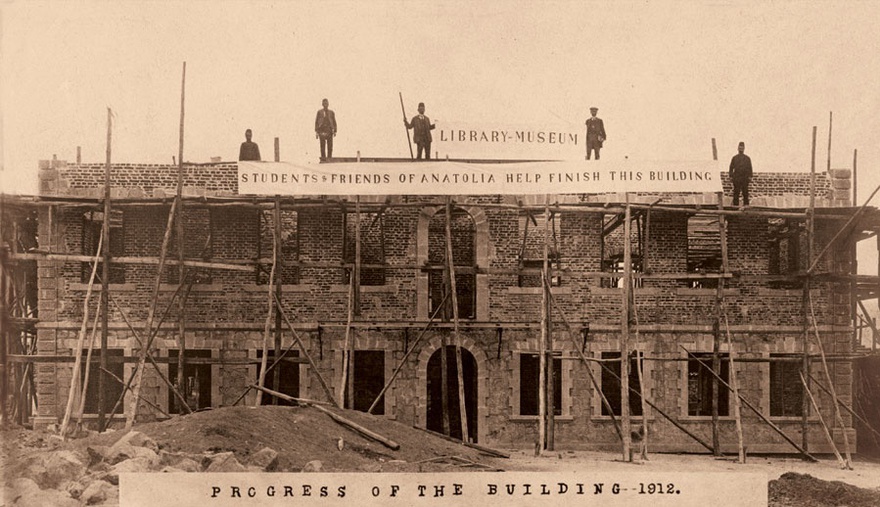

Such a play on perception – an image of hope and potential suffused with ruin – aptly spoke to the underpinnings of Empty Fields, an exhibition as much about the living as it was about the dead. After two years of categorizing and analysing the archives of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), curator Marianna Hovhannisyan unraveled the compelling narrative thread of the Anatolia College in Merzifon, a Protestant missionary school. For this exhibition, she focused on the work undertaken by one of its professors, Johannes 'John' Jacob Manissadjian, to create an expansive natural science collection only years before the 1915 genocide brought his work of discovering and cataloguing Anatolia's flora and fauna to an end. Opening with a timeline of the American mission work in Anatolia from the 1820s until 2010, the exhibition established ABCFM's educational agenda, which was driven by an impulse that was at once theological, cultural and civic. The Anatolia College in Merzifon, a boarding school for Armenian and Greek students from the local provinces, was one of the mission's many educational institutions. The striking photographs on display portrayed the school's multi-disciplinary curriculum, as well as a bevy of extracurricular activities that would rival the offerings of many contemporary high schools in the United States.

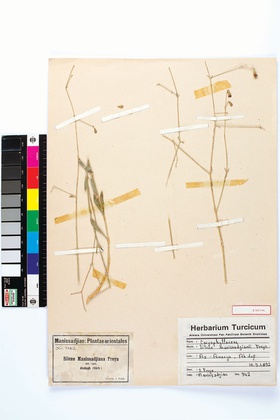

A professor of natural sciences, Manissadjian joined the faculty in 1890 and, as illustrated by multiple photographs of Manissadjian in the field and classroom, began working with students to gather geological specimens. Soon enough he was collecting, identifying and preserving the flora and fauna of Asia Minor, travelling to its peripheries in search of natural objects. These were the building blocks of what would later become a formal collection containing more than 7,000 zoological, paleontological and mineralogical specimens. The museum-library was constructed between 1910 and 1911 – Manissadjian was the museum's sole curator, forging partnerships with scientists across Europe while also shaping a collection that would appeal to the local community. Judging by the archival materials on display, such as the document outlining how to submit an artefact, as well as the information included in the exhibition booklet, he was quite successful in this endeavor.

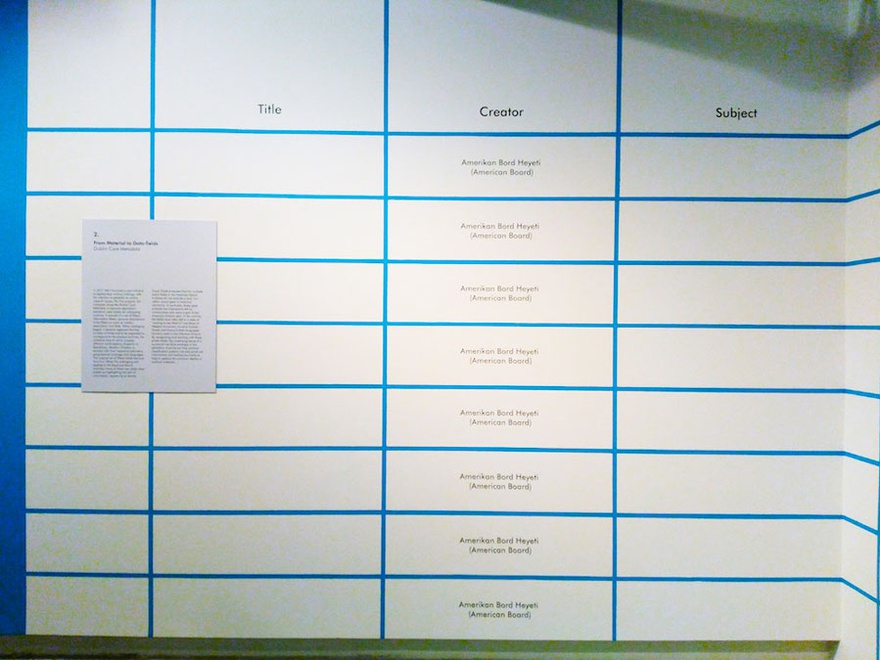

The show was designed around the ABCFM archive but spoke to the theme of archives in general: after observing the myriad empty fields in the archival classification system, Hovhannisyan used these lacunae as structuring guidelines. From her curatorial perspective, the blank fields did not indicate a lack of, but rather a break in historical narratives due to the effects of the 1915 catastrophe.[1] The result was visually powerful, with one wall in the exhibition space made to look like a cataloguing table – rife with empty data fields. Yet the rare archival materials that were presented elsewhere in the exhibition illustrated the richness and depths of the archive, making the metaphor of empty data-fields come across as muddled. Were the many photographs, maps and correspondences on display meant to fill these gaps? Or were we to recognize that many gaps cannot be filled?

For anyone unfamiliar with Turkey's past, the narrative arc of Empty Fields may come across as dry or blasé – an archive is opened and contents are displayed. Yet there are multiple layers to the story of a German-Armenian botanist who established a natural science museum at an American missionary school located in the hinterland of Anatolia during the last decades of the Ottoman Empire. On the surface, there is the inexplicable fact that Turkey, a country whose biological diversity can be compared to that of a small continent, still has no major natural science or history museum celebrating its abundance. This absence is made more painful by the constant drive to develop the country's natural resources and undertake new building projects, often without any consideration for the environmental cost.[2]

However, Manissadjian was able to assemble a vast collection of plants, fossils, shells and coral, butterflies and insects, stuffed quadrupeds and birds, minerals and much more – such an act would be considered forward-thinking now, let alone in the early twentieth century. The breadth of the collection is illustrated in the Catalogue of the Museum of Anatolia College. Handwritten by Manissadjian, it meticulously labels and provides the scientific data for all specimens and showcases in the museum, the majority of which are now lost. Pages from this catalogue were displayed on the exhibition walls, allowing visitors to appreciate the care and diligence with which Manissadjian approached his position (not to mention his beautiful and meticulous penmanship).

What is most baffling, though, is that he began this work in 1917, two years after narrowly escaping deportation, a story described in detail by the accompanying panels and repeated in the exhibition booklet. Unlike the other Armenian staff and students at the college, Manissadjian and his family were released after the missionaries paid a bribe to the gendarmes, and they were allowed to reside at a German-owned farm near Amasya on the basis that Manissadjian's mother was German. In 1917, he briefly returned to the newly militarized Merzifon with the intention of documenting the collection itself and how it was developed. Hovhannisyan framed this act as 'the writing of the disaster', as coined by philosopher Maurice Blanchot – his catalogue foresees the imminent dispersal of its artefacts and is a testimony to the work disrupted by the Great Catastrophe of 1915.

The question of whether the events of 1915–1917 constitute a genocide has bogged down the historical narrative of Armenians in Turkey (and formerly the Ottoman Empire), affecting how scholars and artists investigate and portray this period. Empty Fields recognized and stood witness to the genocide, but did so by documenting a natural science collection that flourished prior to 1915 and was later dispersed and forgotten. The visitor was able to learn about, remember and acknowledge this enriching contribution to the scientific study of Anatolia made by an Armenian, while also facing head on the irretrievability of this particular period in history. Concentrating solely on this catastrophic event, however, provides a limited perspective – one that is mired in political power plays. One need only consider the German parliament's recognition of the genocide on 2 June 2016,[3] or the absurd performance of 'peace choreography' by a dance group wearing Turkish flag t-shirts in New York in April,[4] to understand the contemporary implications of what is, at its roots, a historical debate.

The political nature of these back-and-forth accusations and denials has not only inhibited scholarly research on the genocide, but also on Armenians in the late Ottoman period. In a review of Ronald Grigor Suny's book They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else: A History of the Armenian Genocide (2015),[5] which contains an excellent recounting of the violence around the 'Armenian Issue', the historian Christine Philliou wrote:

[T]he fear of having the Ottoman state's role in mass killings of Armenians exposed to scholarly scrutiny extended far beyond the secreting away of sources from that period; indeed, even research into the social, economic, or political role of Armenians in earlier periods of the empire's history was off-limits, or at least highly suspect.[6]

The tide is turning. As Philliou noted, scholars in the field generally agree that the mass killings of Armenians by the Ottoman state in 1915 did constitute genocide. Moreover, the Armenian past in the Ottoman Empire prior to 1915 (as well as the position of Armenians in the Turkish Republic) has become a more prominent topic of research. Even the Turkish state is ready to acknowledge the profound influence that Armenians had on the late Ottoman Empire, as evidenced by the exhibition A Time for Remembering, Not Forgetting, held in April 2016 at Tophane-i Amire Culture and Arts Centre in Istanbul. Displaying postcards printed between 1895 and 1914, which were supplemented by other archival documents, the exhibition aimed to demonstrate the Armenian presence and influence in different regions of what is now Turkey and, as the opening panel stated, reveal 'the coexistence of all the communities in Anatolia at the beginning of the twentieth century'.

The highlight of the exhibition was, without a doubt, the postcards from the Orlando Carlo Calumeno Collection featuring photographs taken in the late Ottoman Empire. Despite being slightly dull copies, the images displayed were as varied as they were beautiful: Armenian neighborhoods, churches, monasteries, schools (including the Anatolia College in Merzifon), orphanages and hospitals. The postcards were placed on sticks and arranged in two tiered semi-circles in the centre of the exhibition space, whose vaulted brick ceilings allude to its former function as an Ottoman armory; such a historical space added weight to the exhibition's claims of remembering a past that others wish to forget. Although the bottom row required you to stoop down in a physically uncomfortable manner, it was otherwise easy to lose yourself in another time.

It quickly became clear that the show had political underpinnings, which is not entirely unexpected from an exhibition organized by the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The walls were covered with densely packed text in an attempt to promote a particular historical narrative: Turks and Armenians peacefully coexisted until the early twentieth century, when the rise of Armenian nationalism and the turmoil of World War I forced the Ottoman state to relocate this population. In addition to archival materials – again, mostly copies demonstrating the influence Turks and Armenians had on one another in the cultural sphere – a partially separate room contained a smattering of documents from the Ottoman archives that bolstered the official state narrative regarding the deportation of Armenians. Ultimately, this one single event still managed to eclipse the broader historical narratives that could have been distilled from the archival materials in question.

Both Empty Fields and A Time for Remembering, Not Forgetting turned to the archive to provide insights into the role of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in the years prior to 1915. While representing a willingness to explore a shared history, the latter ultimately used the compelling historical objects at its disposal to push a political agenda. Moreover, these snapshots of a particular place in a particular time were static, framed by a perspective on Turkish-Armenian relations firmly rooted in the present.

By comparison, Empty Fields let the archival materials do the talking, and they spoke not only to the rich history of this collection and its creators, but also to their ongoing legacy, even if it is often unknown or unrecognized. Through documents and videos, the exhibition illustrated how thenatural history museum in Merzifon continued to draw crowds in the early years of the Turkish Republic until it closed in 1939, and how, to this day, 130 of Manissadjian's plants are held at the Herbarium of Ankara University, Faculty of Science. Before researchers from the Empty Fields team visited the Herbarium in 2015 and attributed these specimens to Manissadjian, they were kept in the 'anonymous historical' section, demonstrating the traces of erasure that resulted from the catastrophic events of 1915. Yet by displaying these signs of blankness alongside archival materials, the exhibition was able to provide both a before and after to the genocide, documenting what was lost and what traces stubbornly remained.

Empty Fields was on show at SALT Galata, Istanbul, from 6 April–5 June 2016.

[1] Throughout the exhibition materials Hovhannisyan used the words 'catastrophe' and 'Great Catastrophe', which are derived from the concept of Aghed as articulated by Marc Nichanian.

[2] Jennifer Hatam, 'The Olive and the Power Plant' in Sierra Magazine, September 2015. http://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/2015-5-september-october/feature/olive-and-power-plant.

[3] Nick Danforth, 'Why politics and historical reckoning don't mix – especially when Turkey's involved' in Foreign Policy, 5 June 2016. http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/06/05/the-difference-between-germany-and-turkey-is-admitting-to-genocide-erdogan-merkel/.

[4] Chris Summers, 'Pro-Turkey Skywriters Scribble Slogans' in Mail Online, 21 April 2016. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3552070/Pro-Turkish-skywriters-scribble-slogans-New-York.html.

[5] A History of the Armenian Genocide by Ronlad Grigor Suny press reviews, Princeton University Press. http://press.princeton.edu/titles/10426.html.

[6] Christine Philliou, 'The Armenian Genocide and the Politics of Knowledge' review of A History of the Armenian Genocide by Ronald Grigor Suny, Public Books, 1 May 2015. http://www.publicbooks.org/nonfiction/the-armenian-genocide-and-the-politics-of-knowledge.