In Hayden White's essay 'The Value of Narrativity in the Representation of Reality', he writes: 'Narrative might well be considered a solution to a problem of general human concern, namely, the problem of how to translate knowing into telling, the problem of fashioning human experience into a form assimilable to structures of meaning that are generally human rather than culture-specific'[1]. White explains how narrativity and storytelling help us to understand culture, however exotic. It leads one to ask the question: When an artwork utilises the telling of narratives to convey a very specific and complex history, how can information be conveyed and new knowledge produced?

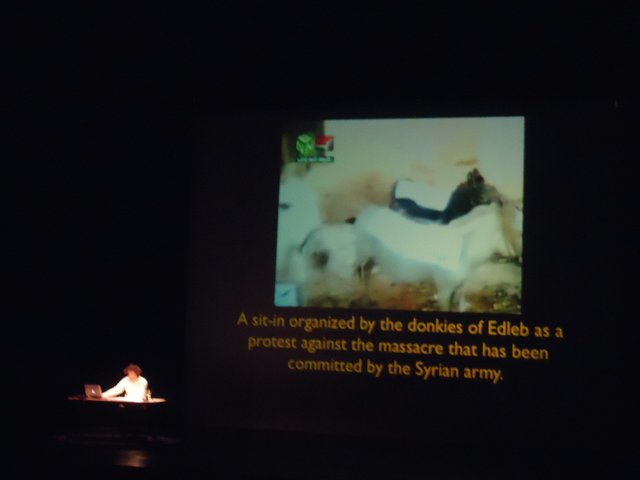

Rabih Mroué performing The Pixelated Revolution, Staatstheater, Kassel, Documenta 13, June 7, 2012.Copyright:

ATP/Ibraaz Publishing, 2012.

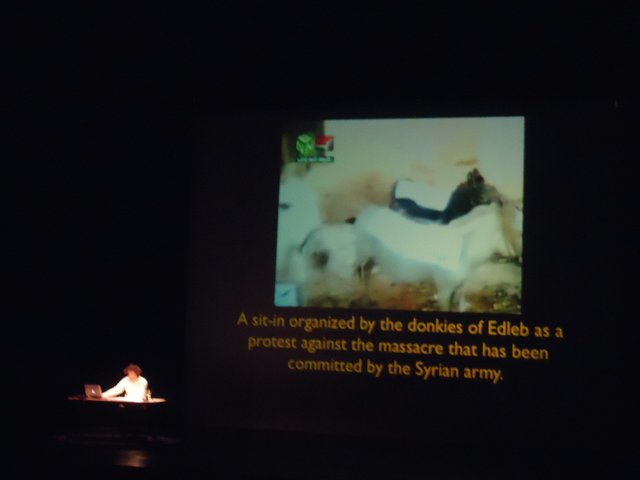

Rabih Mroué stages this in his lecture-performance The Pixelated Revolution (2012), performed at Documenta 13. Here, Mroué performs a narrative to images culled from the Internet and videos posted by civilians attempting to document the latest acts of violence in the ongoing Syrian Revolution. The witnesses have documented and shared their footage to tell of their experience. Mroué plays out the role of selector, interpreter and commentator as he appropriates material into a narrative of his own device.

Dramatically spot-lit and sitting behind his Macbook on the Staatstheater stage, Mroué explores the images he has selected in news broadcast-style. The collection of stills, videos and text projected behind him appear in succession on the large screen. He analyses the cinematic methods of the 'amateur' videos of violence captured on mobile phones and finds similarities between them and the Danish Dogme 95 film collective and its aesthetic. Written in 1995 by Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, the group's manifesto posits the rules of this style of film production as follows: 'Shooting must be done on location, the sound must never be produced apart from the images, the camera must be hand-held, the film must be in colour, filters are forbidden, no superficial action, the director must not be credited'. Mroué identifies these rules in the videos shown, thus generating a new manifesto: the sacred dogma of how to document violence during a time of revolution and indiscriminate death. One by one, he takes us through segments of videos and still images that exemplify these cinematic methods.

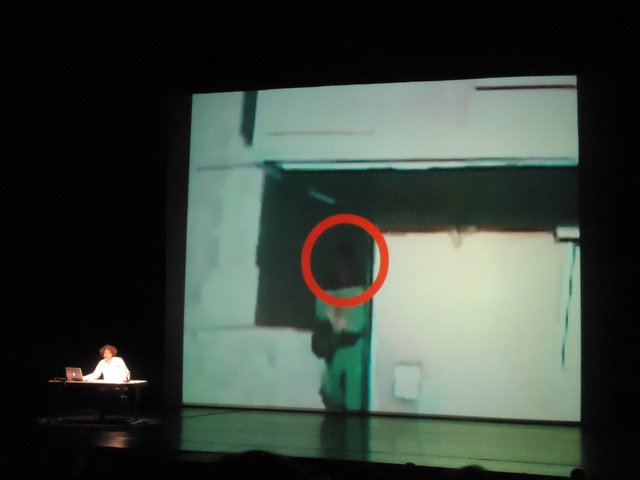

Rabih Mroué performing The Pixelated Revolution, Staatstheater, Kassel, Documenta 13, June 7, 2012.Copyright:

ATP/Ibraaz Publishing, 2012.

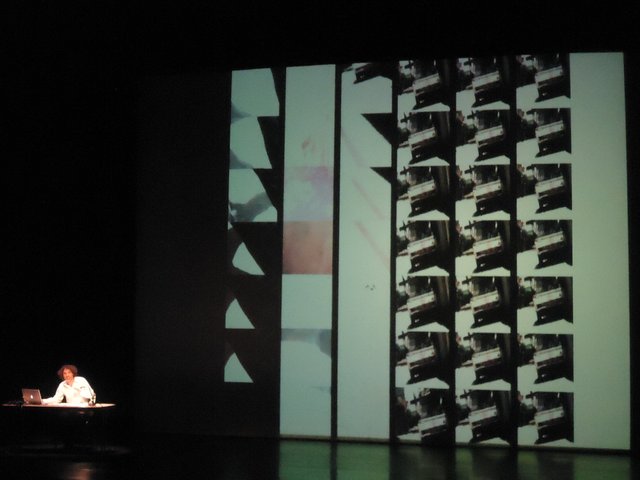

Trying to make sense of the abundance of visual information and the narrative it forges, Mroué produces a grid from these images to systematically analyse the patterns of repetition. This creates another layer of abstraction, further troubling the knowledge one can extract from the chaos of media and the chaos depicted in the images themselves. Whilst theorising on the war of 'bipod versus tripod', 'double-shooting', and recalling the methods of optography - the idea, put forward in the 18th century, that the last image on the deceased person's retina could be extracted - he screens a short video shot from the rooftop of a building. The spectator's eye becomes one with the camera-phone lens, as it gazes down on a narrow street at a sniper anticipating his next target. A moment later, the sniper looks up, clocking the filmmaker and his camera-phone. We know what will happen next, but our eyes remain fixed on the screen as we see the sniper aiming and shooting back at the filmmaker and the theatre audience in turn. The recording device thuds to the ground, shouts are heard and the video abruptly ends. Who is the sniper? Mroué attempts to find out. He zooms in to see the man's face, closer and closer, until any shred of a human feature vanishes into abstraction. Remaining on the screen are shades of computer generated hues that fill the enlarged pixels. With every enlargement, the attempt to reveal the truth only creates a more ambivalent image.

Rabih Mroué performing The Pixelated Revolution, Staatstheater, Kassel, Documenta 13, June 7, 2012.Copyright: ATP/Ibraaz Publishing, 2012.

Mroué is correct to say that borders and separations dissolve as the eye becomes an extension of the camera and the lens. It makes visible the chaos it sees. However, the analysis that can be gathered from seeing this chaos first-hand cannot be computed rapidly once viewed through the apparatus of the computer screen, or in this case, via a projection in a theatre. Mroué wonders about the images we have not seen, the 'killed images', yet, in the images that we do see, much is also missing. The chaos of the bipod is in stark difference to the still and regal image produced by the Syrian state media, as Mroué points out. Here, there is no slow panning of the camera allowing the viewer's gaze to follow the official procession. Instead, the bipod documents an urgent chaos, attempting to simulate what the eye encounters.

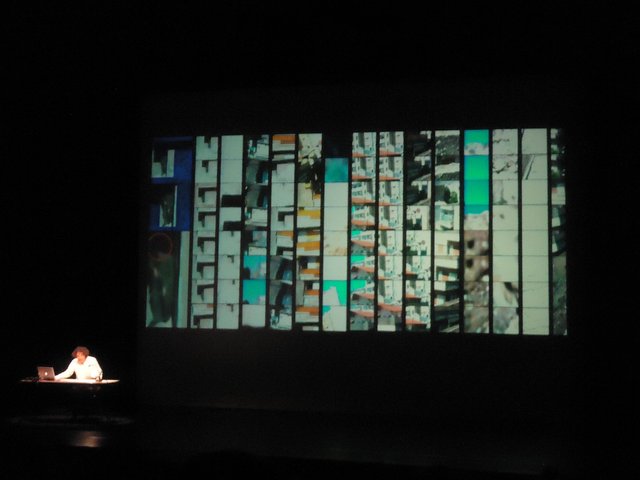

Rabih Mroué performing

The Pixelated Revolution, Staatstheater, Kassel, Documenta 13, June 7, 2012.Copyright: ATP/Ibraaz Publishing, 2012.

Mroué acknowledges the impossibility of substantial evidence available in these images. He attempts to transfer knowledge about looking critically at such footage through the narratives of showing, telling and assimilating. He performs the production of meaning and magnifies the events of fragmented realities as he analyses them using filmmaking methods. Through weaving his narratives, Mroué offers alternate perspectives on events that may once have been too distant to comprehend or too close to consider differently. Drawing out the war of images, he deconstructs the merits of the bipod versus the tripod, offering the spectator a compelling debate in the aesthetics of violence.

[1] White, Hayden, 'The Value of Narrativity in the Representation of Reality', in

The Content of the Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987: 1.

Rabih Mroué performing The Pixelated Revolution, Staatstheater, Kassel, Documenta 13, June 7, 2012.Copyright: ATP/Ibraaz Publishing, 2012.

Rabih Mroué performing The Pixelated Revolution, Staatstheater, Kassel, Documenta 13, June 7, 2012.Copyright: ATP/Ibraaz Publishing, 2012.