News

Freedom to Express: The Abdellia Affair

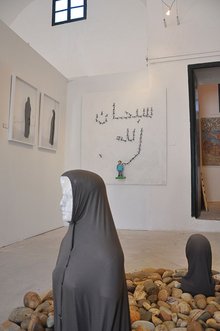

For the past ten years, the exhibition Printemps des Arts has brought together a number of modern and contemporary artists in the heart of the Palais Abdellia in La Marsa, the northern suburb of Tunis. The organisational committee of this meeting of artists and the general public invites gallerists and independent artists to present recent work; a prize is awarded on each occasion, and homage is paid to one of the artists chosen by the organisers.

This year, the organising committee was headed by the artist and curator Meriem Bouderbala, who wanted to inscribe the event within the movement of democratic emancipation the country is experiencing, with the hope of giving local artists wider international recognition. She described the event in the following way in the accompanying catalogue for the fair: 'In the current context, it is all about occupying cultural territory, of allowing everyone access to it and contributing to a strong democratic cultural constitution that demonstrates the strength of Tunisia's creative potential [...] For this first edition of Arts Fair Tunis, Le Printemps de Arts, which has been organised as an act of resistance, it is important that we create a dynamism by calling upon Tunisians, on international aid, on support from institutions, foundations, artists and gallerists, and upon partnerships with those actors who are recognised throughout the art world. Synergy is a force, our force, as we saw in the actions of Tunisian civil society, present in the street as soon as the liberty of its citizens was attacked'.

Preference was given to Tunisian gallerists and independent contemporary artists, selected to exhibit new work produced for the occasion from the 1st to the 10th of June, 2012. The exhibition opened as planned, and was accompanied by the exhibition of several pieces at the Bchira Art Centre to the west of Tunis, and both the Bchira Art Centre and the Palais Abdellia welcomed high numbers of visitors over the ten-day period. The exhibition was widely covered in the online press.

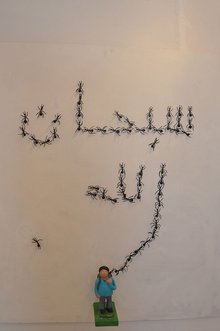

During the last day of the exhibition, however, three people, including a bailiff, asked the Kanvas gallery to remove two paintings judged offensive before 6pm. They warned that they would be back to make sure that the paintings had been taken down. The bailiff took several photos of them, which he later photocopied and handed out in the mosques. The gallerist refused the ultimatum and alerted the artists and media of the threats. At 5pm, a group of sympathisers arrived at the exhibition, among them representatives from the political parties who had come to support the artists. It was at this moment that those who objected to the work appeared, among them Salafists, and began to protest violently, confronting the police who were present at the exhibition. A campaign of denigration against the exhibition and the pieces, judged to be an insult to religion, began to gather pace on Facebook and other platforms. Among those pieces was one representing the night of the Maraaj, entitled La Kabaa et le Prophète. This image turned out to not even be part of the exhibition, but taken from a website showing works that had been exhibited in Senegal.

That night, works in the exhibition were targeted by the extremists and from that moment the polemic began to gather steam, even reaching as far as the sermons given in mosques.

The artists that had exhibited at Bchira Art Center and whose names were visible on Tunisian art websites began to receive death threats, which were both persistent and violent. The next day, the Ministry of Religions Affairs and the Ministry of Culture both condemned the incriminated pieces and raised the issue of limiting creativity in order to respect sacred values and so as not to incense public opinion.

Following this declaration, using the supposedly sacrilegious artworks as a pretext, several incidents of violence and pillaging took place in different towns, police stations, courts and municipalities. Demonstrations called to protect Islam and to pass a law criminalising all attacks on the sacred. The debate moved on to the constitutional assembly and provoked waves of unrest. The fatwa launched against the artists was immediately condemned by the government, who feared the situation was getting out of hand.

The Ministry of Culture condemned all forms of violence and closed the Palais Abdellia and called for an inquest into Le Printemps des Arts and the responsibility of the organisers. The threatened artists organised collectives alongside NGOs and various syndicates and prepared their legal defence. Several meetings, declarations and motions of support took place. The debate surrounding freedom of expression and the limits placed on creativity gained momentum in the national media.

Today, the Palais Abdellia has reopened, and the inquest into the exhibition is still in progress, while the bailiff who was present on the last day of the exhibition has been condemned to a month's imprisonment for inciting hatred. The artists involved have been deeply affected by their ordeal. It must be said that the cultural scene is struggling to deal with events. And even if, according to some, we mustn't get overly alarmed by these threats – the declarers of which must be brought to justice a slump in creative life and a constant fear for freedom of expression the consequences weigh heavily on us: prejudice and trauma for the artists themselves, but also for young people wishing to become artists. This image of Tunisia – one depicting a slump in creative life and a constant fear for freedom of expression – is in fact far from corresponding to the reality of its society and modernity. This is why, whatever our ideology, we cannot remain insensitive to this mode of intimidation that threatens the vital force of a society, in the near future, or for a long time to come.