Projects

Some Pachinko Pieces

On Silence and Noise in Times of Crisis

Put the sound on loud on your computer while reading this piece. Or put it to mute.

How do you usually work: do you listen to the sound of – ping – an email coming in? Does it distract you from what you do?

Mohsen Makhmalbaf's 1998 film Sokout (The Silence) tells the story of a little blind boy, Khorshid, and the circumstances of his life. Khorshid is distracted by sounds, music, beautiful voices, the crunch of crisp bread, and the buzzing of bees. Beautiful sounds let Khorshid forget where he is – he becomes distracted and has to follow them. He plucks his ears with his fingers, trying to avoid getting lost and instead follow his duties: Khorshid needs to make money from his musical instrument tuning job so that he and his abandoned mother can pay the rent before they are thrown out by their landlord at the end of the month. The landlord's impatient knock on the door becomes a reminding noise of the pressing social realities throughout the film.

The film is regarded as an example of director Makhmalbafs 'poetic period' – lots of references to the Persian poet Rumi can be found. It doesn't follow a classical narration; instead strong symbolism coming from Sufi ideas and traditions defines the film's imagery. 'As for the flowers, each of their petals is a tongue, if only we could achieve the kind of silence that enables us to hear their words', writes Rumi.[1] Khorshid's friend Nadereh, the second main character in Sokout, puts flower petals on her fingernails and decorates her ears with cherries, while starting to dance to 'ba-ba-ba-bom' – the opening chords to Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 (1804–08), the knock on the door.

In his text 'Listening for an "Authentic" Iran: Mohsen Makhmalbaf's film The Silence', Lloyd Ridgeon writes:

The silence of Sokout is this sound that enables Khorshid to create meaning in his world; he can distinguish between the bees that land on honey and those that rest on dung, just by listening to their buzz. In order to create, Khorshid has to listen, not just in a functional sense, but rather to listen with patience and care in order to yield a deeper understanding of the realities behind the appearances of things.[2]

Somewhere online I read a review of Sokout from a disappointed viewer: 'But virtually nothing happens in The Silence, and what little does happen... well, let's just say it happens.'

Well, let's just say it happens.

I try to imagine what would happen to Khorshid with John Cage's 4'33" (1952).

Would he get distracted from it in some way?

Are Cage and Makhmalbaf talking about the same kind of silence? Is John Cage's silence a conceptual silence? A poetic silence? A political silence?

Is silence the same in all contexts, everywhere?

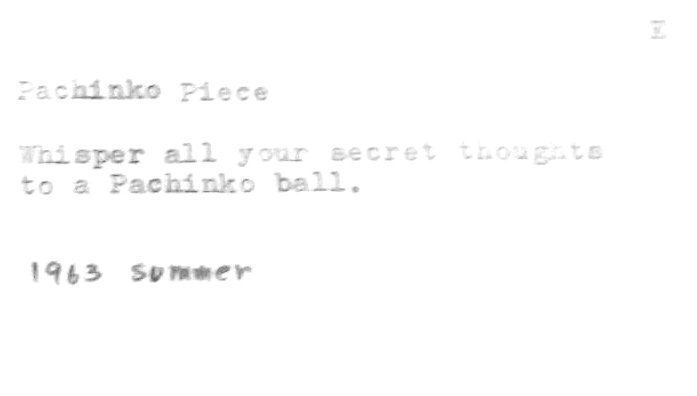

In December 2015, I visited a large-scale exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo of work by John Cage's contemporary, Yoko Ono. In one room, a collection of her famous 'Instruction Pieces' were exhibited – small numbered papers with typed instructions for (imaginary) action and performances. I read through all of them. Some felt familiar, while others not at all. One that I had never seen before was titled Pachinko Piece (1963).

Yoko Ono, Pachinko Piece, 1963. Installation view, FROM MY WINDOW, Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo. Courtesy of the author.

A pachinko ball is a pinball used in Japanese arcade games. The lone player fires balls into the machine, which then cascade down through a dense forest of pins. If the balls go into certain locations they may be captured and sequences of events may be triggered that result in more, ideally heaps, of pachinko balls being released. While spending autumn in Japan last year, I found that there were more pachinko game halls than supermarkets: immensely popular yet weird everyday places of luck, despair – and noise. The noise in a pachinko hall is deafening – there are rows and rows of screaming, jingling, gibbering and chiming machines next to each other.

'One doesn't need to whisper; one can shout and still no one hears one's secrets', I think to myself, reading Yoko Ono's piece.

Whispering secrets in noise to a small metal ball is still quite a beautiful and poetic thing.

In Japan I felt that there was a lot of this – of beautiful whispering in noise.

I also felt that the notion of silence was something completely different from what I was used to.

I don't want to leave this feeling here as a vague metaphorical or spiritual thought, but I will come back to it. I also want to try and relate it to a very actual, political sphere. What do I whisper to the ball? It doesn't need to be poetry, does it?

I am wondering whether there could be something like a poetic yet political silence, or a political yet poetic noise.

I initially came to Japan to conduct research for a project linked to Iranian immigration to Japan – a very particular immigration history, whose narration was formed at the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s with political and social dimensions that might be viewed as very symptomatic of each countries' policies. The number of Iranians in Japan began to increase significantly in the late-1980s and early 1990s. Iran, by that time, had suffered significantly from the economic consequences of the 1979 revolution and the long years of the Iran-Iraq war. A large number of Iranian youth, mostly male and unemployed, left Iran for Japan hoping to find high-paying jobs at the outset – and for the duration – of the bubble economy; they were able to enter and exit Japan freely thanks to a mutual visa exemption agreement between Japan and Iran, launched in 1974. However, in 1992, prompted by worsening economic conditions, Japan terminated this visa-free agreement with Iran, and began serious efforts to deport illegal overstayers. The total size of the Iranian population would shrink dramatically over the following decade and the stereotype of the Iranian immigrant became linked with illegal immigration, drug dealing, and smuggling. The number of new migrants remained significantly smaller compared to the number of deportations that occurred after 1992.[3]

Returning to Sokout: is it possible to imagine Khorshid as an immigrant and the landlord as a deportation officer? In what reality can Khorshid – the precarious – live in? What is his alternative to fit into the world?

The history of Iranian immigration to Japan needs to be seen in relation to the fact that in Japan foreigners or 'gaijins' (outside people) make up only around 1.5 per cent of the country's population.[4] Japanese immigration policies have long been based on the principle of marginalizing foreigners economically, excluding them socially and politically, and forcing them to assimilate culturally. In 2015, Japan accepted only 27 asylum seekers out 7,586 applications – and this number was a record, with an almost 100 per cent rise from 2014. It also means that 99.6 per cent of applicants were rejected in a year that faced the worst migration and refugee crisis since the Second World War.[5]

While in Japan, I found it very hard to get to know more about the remaining Japanese-Iranian diaspora. It was simply too small or, in the best case, well assimilated, trying to escape stereotypes of 'the illegal Iranian drug dealer' of the early 90s.

Assimilation is accomplished by silence, or is it?

I myself, with the highly problematic position of a foreign artist 'on a mission' in Japan, experienced a lot of silence when addressing these themes. At the same time, they created a lot of noise in Europe: the refugee crisis was in the headlines everywhere with outcries of anger about human rights violations and cruel EU border politics clashing with right-wing populism and voices against immigration, shouting in one's face without any restraints. To me, it is very clear which of these two kinds of noises I consider relevant and necessary, but looking at present European politics and how differently different people consider relevance, any kind of objective clarity vanishes.

Is noise relevance? How do you consider it? Revolution, social and political change, and engagement are always accompanied with the urge to 'make one's voice heard'. How is it achieved?

How can one interpret silence in this? Is it an escape? Indifference? Passivity? A residue of fear?

How is it interpreted politically? How is it used to control political agendas?

There are quite a number of articles on the different applications of silence in Japanese culture and communication. Most importantly, it seems that in Japan one is aware of non-verbal communication as a social event. Silence might be used as a form of respect but it can also function as a form of passive resistance or is used to express dissatisfaction. The meanings might differ but they show that, in Japan, silence might be used in an active way; a way to gather information. Active silence may have the possibility to resolve something, its idea leaves space for time/fate/life/other ideas/[blank]. There might be a link to an Iranian silence in this, but I am not really sure.

The beauty of ambiguity in silence lies in imagination. Ironically, that's the ugliness in it, too.

What becomes noise, when one cannot separate it into lower voices? It might become what fear is made of. It might become deafening.

What becomes silence? It might be nothing, but a nothing with an influence, maybe similar to deafening.

In a political crisis there is no place for poetry, or is there?

Watching Sokout, one might miss its political controversy. It was banned by censors in Iran from 1997 until 2000, like quite a few other movies by Makhmalbaf. The film is set in Tajikistan, with some geographical distance to Iran, in a lush landscape with warm, vivid colours. There are weirdly intimate, sensual and undefined erotic moments that, with the film's main characters being children, might feel disconcerting. The move makes sense from the Iranian director's standpoint, being less restricted in approaching certain subject matter with child characters than he would be with adults. Like Nadereh in Sokout, children are allowed to indulge more, say other things, move differently – and the censors have a harder time finding reasons to enforce their position. In one scene, Nadereh is scared of a man wanting to enforce hijabs. Khorshid's life is defined by many societal difficulties – the pressing need to make money, the need to fit into the 'real'. Still, both of them sensually define their own world, a spirited alternative world of the present moment – a definition that in the film is by far the stronger one. In an interview, Makhmalbaf says:

I think that throughout the ages there have always been a lot restrictions on people against being active in politics or even commerce here, so there was a tendency for people to participate in art and spiritual things. It has become the mirror that reflects the Iranian people.[6]

The silences and sounds in Sokout have a deep political message. One that celebrates the liberating moment in art and its power on defining reality.

Yoko Ono and John Lennon dedicated a song to John Cage with Two Minutes Silence on the album, Unfinished Music No.2: Life With The Lions (1969). It is the same as 4'33", only with two minutes and 33 seconds missing, isn't it?

I try to feel at least some seconds of it in the pachinko hall, but I am failing with all the distractions. I still record myself and whisper my secrets, following Ono's instruction, trying to get close to it.

The videos in this piece should have been GIFs, repetitive images of silence and noise – but GIFs have no sound. I am failing again. That's why I put them on COUB; a strange compromise.

I wonder who else has ever carried out Ono's instructions and continue whispering more secrets to the ball. The next Pachinko Piece could be listening to the ball telling all of them.

[1] F. Keshavarz, Reading Mystical Lyric: The Case of Jalal al-Din Rumi (Columbia: University of South California Press, 1998), p. 61.

[2] Lloyd Ridgeon, 'Listening for an "Authentic" Iran: Mohsen Makhmalbaf's film The Silence (Sokout),' in Iranian Intellectuals: 1997-2007, ed. Lloyd Ridgeon (London: Routledge, 2008), pp. 139-153.

[3] See: Behrooz Asgari, Orie Yokoyama, Akiko Morozumi, and Tom Hope, ' Global Economy and Labor Force Migration: The Case of Iranian Workers in Japan,' Ritsumeikan Journal of Asia Pacific Studies, Volume 27, February 2010. http://www.apu.ac.jp/rcaps/uploads/fckeditor/publications/journal/RJAPS_V27_Asgari_Yokoyama_Morozumi_Hope.pdf

[4] 'Foreigners make up 1.5% of populace,' The Japan Times, 29 August 2013, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2013/08/29/national/foreigners-make-up-1-5-of-populace/

[5] 'Japan rejected 99 percent of refugees in 2015,' Al Jazeera, 24 January 2016, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/01/japan-rejected-99-percent-refugees-2015-160124070011926.html

[6] Neil MacFarquhar, 'An Unlikely Auteur From Iran,' The New York Times, 8 June 1997, http://www.nytimes.com/1997/06/08/movies/an-unlikely-auteur-from-iran.html