Reviews

Space Refugee

Halil Altındere at Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Berlin

In the song Life on Mars, David Bowie longed for a life on Mars as an escape from 'the freakiest show of the Lawman beating the wrong guy'. While the European Union and Turkey are discussing where to settle refugees and Turkey is insisting on its contentious politics, like Bowie, Halil Altındere looks at the sky and contemplates receiving salvation in space, a supposed no man's land, in the exhibition Space Refugee at Neuer Berliner Kunstverein Berlin. Curated by Kathrin Becker, the exhibition was premised on sending refugees to Mars and researching the potentiality of starting a civilization from scratch.

Since the 1990s, Halil Altındere has used humour in his work as a way to criticize nationalist and patriarchal apparatuses or hegemonic structures. For instance, in the painting Portrait of a Dealer (2010), renowned gallerist Yahşi Baraz's head emerges from a famous painting by artist Burhan Doğançay. More recently, Altındere's work has hinged on the controversy of immigration. In the video installation Köfte Airlines (2016), exhibited at HAU2 Berlin as a part of Berlin Art Week as well as the festival The Aesthetic of Resistance: Peter Weiss 100, refugees are filmed sitting on an airplane in parking position. Mockery flirts with sadness.

In the case of Space Refugee, Altındere proposed speculative fiction as a solution to the 'refugee crisis' (as described by the European media). The story of the artist's protagonist, the former Syrian cosmonaut Muhammed Ahmed Faris who illegally crossed the border and took refuge in Turkey, was presented with life-size models, paintings, videos as well as virtual reality headsets across three rooms. In 1987, as a part of the Interkosmos programme, Faris flew to the Mir station on Soyuz TM-3 and became a national hero. In 2012, he supported the opposition to the Assad regime and had to flee his country, where streets are in fact named after him. Nowadays, the cosmonaut shares his knowledge as a teacher at the space education centre Ali Kuşçu Space House in Istanbul.

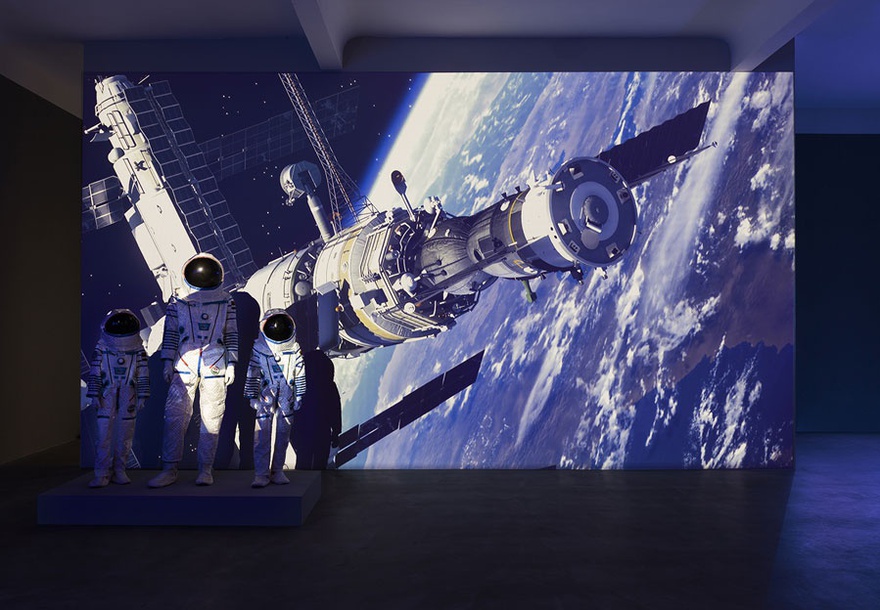

Within the exhibition, paintings and replicas of socialist realist posters greeted visitors with blue-neon-lit frames shining in a single darkened space creating a kitsch sci-fi atmosphere. The originals of the posters featured in Muhammed Ahmed Faris Stamp I (2016) and Muhammed Ahmed Faris Stamp II (2016) were printed in the Soviet Union to celebrate the partnership between Russia and Syria. Copied from photos originally from 1987, paintings such as Muhammed Ahmed Faris with Friend (2016) or Muhammed Ahmed Faris with Friends I and Ahmed Faris with Friends II (2016) depict Faris smiling proudly alongside Russian cosmonouts Aleksandr Stepanovic Victorenko and Alexandr Pavlovich Aleksandrov. Three life-sized models (one large and two kid-size) with space suits, inspired by Faris' original suit, 3 Cosmonaut Family Costumes (2016), hint of the futuristic story that waited in the next rooms, where the video Space Refugee (2016) was projected on a big screen and a virtual reality video surrounded by various models was placed.

The video Space Refugee (2016) starts with a summary of the-proud-to-be-Syrian cosmonaut's journey: Faris talks about his exhausting escape from his homeland to Turkey as well as the importance of Mesopotamia in the history alongside the archival footages of young Faris in the spacecraft. Interviews with scientists report on ways to build a civilization, this time with the help of 3D printers rather than stones. Istanbul-based architecture office Autoban talks about their design The Architectural Design for Mars Refugee Colony (2016) for new housing in space – the shelter that 'offers protection against radiation and sandstorms' looks like a big circular cave. A specialist on space law mentions the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which declares that no one can own outer space and no nation can claim land in space. At one point, the artist asks Alper Aydemir and Umut Yıldız from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at NASA about the possibility of life on Mars and how they imagine world dwellers might transform into Martians.

In the next room, the 360-degree video viewed through VR goggles, Journey to Mars (2016), demonstrates a possible future with an imaginary Mars colony complete with glasshouses growing plants without soil. Originally shot in Cappadocia Turkey, the video features three people in space suits – a man and two kids, understood to be the cosmonaut family who owns the aforementioned costumes – who guide viewers through the surroundings of Altindere's imaginary Mars, which recalls the dystopic sci-fi movies of the 1960s. Surrounding the pedestal on which the VR goggles were placed, viewers encountered a display mimicking a museum for space education; among the exhibits were proposals of planting technologies such as Space Aero Garden (2016), a model for an experiment to easily grow food without soil, and the robotic car Palmyra Mars Mission Rover (2016), designed 'to collect information on the climate, geology and existence of water on Mars' surface'.

What does the notion of nation denote if we are to imagine one on Mars? If we stand up and sing a Martian national anthem, will it be absorbed into silence through the space that Mars represents? With bigotry and hatred spreading across the world, particularly among the extreme right, these are questions the artist appears to confront in this exhibition. However, perhaps the artist could have gone further with undoing the claims on the future that have been made by various state regimes and political ideologies. After all, regarding the forced vagrancy and the days spent in limbo with a blurry future, aren't refugees already on some kind of Mars?

Space Refugee was on show at Neuer Berliner Kunstverein Berlin from 15 September to 6 November 2016. For more inforamtion, see: http://www.nbk.org/en/ausstellungen/_altindere.html