Reviews

Questions of Collectivity in the Absence of Connectivity

On Qalandiya International 2016 in Ramallah

While the intention behind Qalandiya International is subversive, it is still weighed down by the heaviness and sadness of its name. 'Qalandiya' is the name of the Palestinian village adjacent to what was once an international airport. It is also the name of one of the largest populated refugee camps in Ramallah, and the main checkpoint separating the West Bank's southern and northern districts from each other, and Jerusalem. It is the place where the chaos, fragmentation and tension created by the Israeli Segregation Wall is most literally visible. And while 'Qalandiya' as an Israeli checkpoint is a syndrome of the Palestinian contemporary political reality, it is also a specific geographic manifestation of this syndrome, too. The name 'Qalandiya International' points to the Israeli occupation's imposed fragmentation of the landscape, but it struggles to find a truly poetic resonance as a metaphor.

Initiated in 2012 as a biennial event that takes place in October and November, Qalandiya International (Qi for short) was founded and organized by nine Palestinian art and cultural institutions: A.M. Qattan Foundation, Riwaq, The International Academy of Art-Palestine, Al Hoash-The Palestinian Art Court, Al Ma'mal Foundation, Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center, Ramallah Municipality, The Palestinian Museum, and The Arab Cultural Association. Together, these institutions act as a steering committee that selects the theme for each edition, and oversee a joint funding structure that manages the necessary logistical coordination of the event.

Qi is somewhere between a festival and a biennial, whereby the participating institutions present their main programmes within some kind of interpretation of a selected theme. The result is an overwhelming number of artistic events that are tightly coordinated within a common calendar but struggle to come together as a comprehensive experience. Some may be inclined to think that the institutional collaboration that constitutes how Qi is designed and curated is manifested mostly on the level of coordination rather than through an artistic and conceptual exchange among participating institutions. Yet, while more challenging, the emphasis on creative conceptual exchange between institutions is both politically and artistically necessary. Without this focus on artistic collaboration, Qi runs the danger of creating a comforting illusion of collectivity that only glosses over the political and geographic fragmentation that it is critiquing.

Indeed, the very act of independent institutions coming together to create a platform for a collective structure amid the larger failure and fragmentation of the political leadership that has thwarted Palestine into a long coma of stagnation, makes Qi a subversive political and cultural gesture within itself. One may even argue that it may very well be the main 'project' of the event, and thus still has the most potential to grow. 'This institutional dimension remains the most interesting aspect of QI', British artist, writer and editor Nicola Grey whispered in my ear, during the opening press conference for the 2016 edition on 6 October 2016 at Al Sakakini Cultural Center in Ramallah, one of the sixteen institutions across London, Amman and Beirut as well Haifa, Jerusalem, Ramallah and Bethlehem participating QI's most ambitious edition yet.

So how was this edition experienced within the framework of Qi2016's inter-institutional collaboration? Titled This Sea is Mine, Qi2016 explored the theme of 'return' – what Qi's curatorial statement acknowledges as a central issue for the Palestinian cause, which 'has been reduced to a rigid slogan' while the 'project' of 'Return' itself 'has been diminished to merely the symbolic realm of visual culture'. This sets up high expectations and complex challenges, given the risk of becoming but another repetitive rhetorical statement and gesture that falls into the symbolic realm of visual culture that the curatorial statement critiques. At first glance, it is hard to evaluate whether the theme 'return' itself offers an inspirational instigation for artistic production. Part of the problem is that 'return' is not really a theme. It is a statement and an individual and collective political aspiration – one that is vested with very real questions. To this end, I was curious to see how this theme unfolded throughout the exhibitions in Ramallah in particular.

Honouring Qi2016's title This Sea is Mine, Riwaq carved a trajectory for reconnecting to the seascapes that outline the geography of historic Palestine for those who live in the West Bank and are denied access to them. In keeping with their longstanding contemporary art programme, A Series of Un-curated Events made clear Riwaq's institutional role as artistic contributors, rather than outsourcing the events to an external curator.Most notable from this series were two tours. The first was Sarab, which comprised of a four-wheel drive to some of the lesser-known landscapes around the Dead Sea that highlighted the historic political conditions of the Palestinian wilderness. The second, Seaview, constituted a journey into Rantis, a Palestinian village overlooking the Mediterranean coast from the contested political delineations of the Green Line. Guided tours have been a trademark of Riwaq's activities, used to activate the historic villages and buildings they have renovated, encourage local tourism and revive the tradition of Palestinian cultural exploration of the landscape. The tours they created for Qi2016 were less about show and tell, and more about creating an experience that combined some elements of hiking, adventure, intimate settings for sharing food, and the nostalgic practice of listening to the stories of elders. Artistic gestures were also made along each tour, such as the installation of a large-scale golden frame that created a backdrop for interesting group photographs positioned at a point overlooking the Dead Sea.

Also working across multiple sites was Ramallah Municipality's exhibition Sites of Return, curated by Sahar Qawasmi and Beth Stryker, which stood out for its newly commissioned public performances and interventions that transformed multiple public and private locations into sites of collective intimacy and connectivity that embraced the general local public. Mirna Bamieh's public performance Potato Talks: (Up)rooting-Ramallah Edition (2016) created multiple 'one-on-one' set ups in Al Manarah, the main roundabout in downtown, where both professional storytellers and members of the public shared their memories and stories of the sea while casually peeling potatoes. Meanwhile Nida Sinnokrot's performative intervention Flight-Jalazone (2016) created a beautiful tableau onto the sunset skyline from the rooftops of Jalazone refugee camp, located on the outskirts of Ramallah city. The artist attached small LED lights to several flocks of pigeons and released them into the sky. Since Sinnokrot's initial performance, his artistic gesture has been adopted by the community as a new tradition to celebrate weddings and other festivities.

Sites of Return reached out to different publics and attracted 'the coincidental type of audience' that ordinarily may not necessarily attend art exhibitions. Ramallah Municipality heavily advertised the exhibition through its big billboards across the city. This ensured some much needed traffic into Qi2016, which – despite its ambitious scale – struggles with local audience attendance. This may in part be due to the overwhelming number of Qi events taking place within a tightly packed timetable, which did not take into consideration local audiences' working hours. It also did not help that each institution primarily only advertised their own events rather than the overall Qi program. This lack of joint promotion added to the overall sense surrounding Qi's project as being one of gestural institutional collaboration through the practice of coordination rather than a conceptual and holistic curatorial event, as expressed by scheduling and marketing different components as a cohesive programme made up of distinct yet succinct parts. The latter approach would have capitalized on the added value of creating artistic momentum, urgency, curiosity and buzz among more local audiences to attend the Qi2016 events as they unfolded. Most importantly, it would have opened up a space for contemplation and interpretation of the connections among the various programmes once considered collectively.

In reality, some of the presented institutional programmes like Cities Exhibition by Birzeit University Museum, The Young Artist of the Year Award (YAYA) by A.M. Qattan Foundation, and The Jerusalem Show by Al Ma'mal Foundation – which have existed for years outside of the QI framework – already had a historical precedence and articulated goals that they needed to live up to, with or without the frame of Qi. Observing the last few editions of YAYA, which is a competition geared towards supporting Palestinian artists under 30 years of age, it is not clear if the competition gains from operating within Qi's thematic structure. One may even argue that working within a determined theme has limited the possibilities for unexpected content and experimentations with artistic form among the shortlisted artworks selected. Over the last few years there has been a repeated focus on narration, preservation of memory in relation to Palestinian political history, as well as a mostly male-centric revisitation/celebration of Palestinian art history narrowly focused on the mediums of painting and drawing.

The fifth edition of Cities Exhibition, curated by Yazid Anani, worked within a pre-scheduled focus on Gaza city. Titled Reconstruction, the exhibition tackled the possibility of knowing and reconnecting to Gaza from afar due to the imposed Israeli siege that denies access to and from Gaza. One of the cheekier and truly subversive works that tackled the dilemmas of collectivity in the absence of connectivity was a video piece entitled Hose after Hose by three collaborating International Academy of Art-Palestine students Hamza Amleh, Noora Said and Waseem Fouad. In the video, the artists go around different houses in the West Bank asking people to donate a piece of their water hose and drinking water in order to create a water pipeline from the West Bank to Gaza. The video's visuals are comprised of creating this long water hose, a desired line of connectivity, while the audio is a mixture of the anonymous responses that were collected. The request itself is naive, simple and clearly unrealistic, yet it hits a dark spot given its provocation, since the West Bank is also suffering from a water crisis. We hear different men, women and children respond:

'Why don't you fix the water crisis here first?.'

'If they make peace with Egypt they might send them water from the Nile- that is if there is still water in the Nile.'

'From a security point of view would the Israelis allow it? Of course we are happy to help but would the Israelis accept it?'

'This is the responsibility of the government.'[1]

Overall, the piece challenges the rhetoric of Palestinian unity and connectivity. Most importantly, the responses confront us with the very real challenges of 'sharing' and independent collective agency outside of formal governmental and institutional structures. I was left reminded that the West Bank's relationship towards Gaza has been reduced to one of 'saving' or 'giving', heavily entrenched within the foreign discourse informing 'aid' practices rather than an active place of solidarity where things are exchanged. After all, if there ever was a possibility of a water hose erected from the West Bank to Gaza, it will most likely be engineered in Gaza.

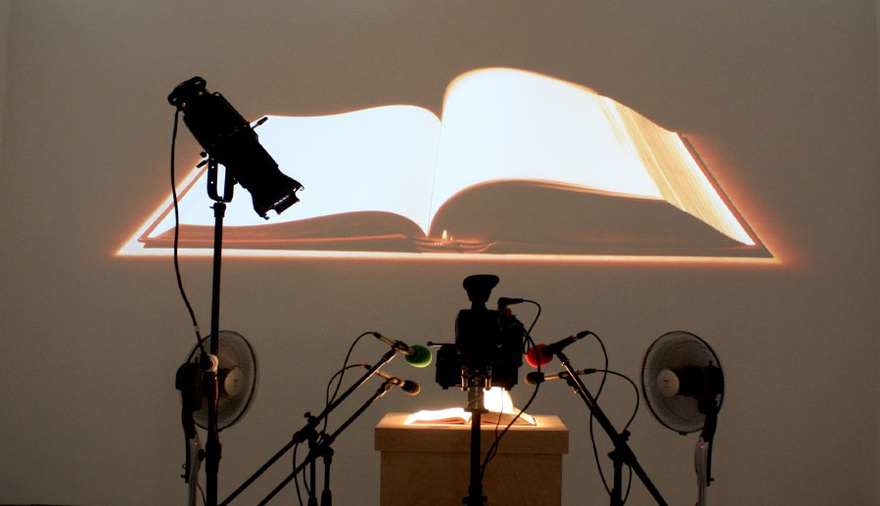

In the same exhibition, artists Nida Sinnokrot and Oraib Toukan dealt with the apparatus of representation around Gaza. Sinnokrot's installation Exquisite Rotation (2016) contains his signature use of seemingly simple technology to produce a language that is at once allegorical and experiential. Audiences gasped in awe as they peeked into the installation room, which did not allow visitors to walk through it, but rather forced people to consider an external view of what can be described as encapsulating 'the bigger picture' – the skeleton of the political apparatus. An empty book is set on a pedestal surrounded with microphones that capture the sounds of two fans, set opposite one another to the left and right, wrestling with the empty pages of the book. A video camera sits atop of the book feeding into a live feed projection of what feels like an endless loop of one empty page flipping once to the right, only to be flipped over again to the left. A testament to the strength of the piece is that it invites and carries different interpretations. Within the context of this exhibition around Gaza, it suggested that, despite all the microphones and cameras, somehow we don't really see Gaza. Images and words are rendered invisible and ineffective when caught within the vicious loop of internal Palestinian political division and polarization.

In contrast, Toukan's video When Things Occur (2016) delves into the details of the content: the opaque pixels of the journalistic photographs that document the realities of Gaza. Set up from the position of a laptop, the artist scrolls over the surfaces of iconic photographs that emerged from Gaza in the summer of 2014, sometimes zooming in creating alternative crops of these images or acknowledging their fragility as digital pixels, other times surfing the spaces that these images inhabit online, as we listen to the artist's numerous Skype conversations with the journalists, fixers and drivers that capture (produce) these photographs. These protagonists at times sound somber or cold, as they matter-of-factly describe their conundrum of reporting on events that impact them personally, while also negotiating a visual balance of emotional horror, destruction and bloodshed that allows their images to circulate online. The effect this creates for the viewer is that the photographs feel like they are still being processed, and thus remain within the realm of the potential 'to be seen'. Toukan's piece stakes a place for itself among other contemporary videos and films by artists Joshua Oppenheimer, Renzo Martens, Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin, which have tackled similar themes.

Paving a new way for a return to folklore, O Whale, Don't Swallow Our Moon, the first solo exhibition in Palestine by artist Jumanna Emil Abboud, offered a nuanced interpretation of Qi2016's theme and a radically different aesthetical approach. Curated by Lara Khaldi and produced by Khalili Sakakini Cultural Center, the exhibition brings together older and more recent works by the artist, whose aesthetic is marked by a playful childlike sensibility that borrows its iconography from Palestinian folk tales and folkloric traditions.

Walking into the exhibition felt like stepping into Abboud's whimsical and magical world. 'Ein' in Arabic is the word for 'eye' and 'well', a double meaning that Abboud carries throughout the exhibition which opened with A Happy Ending: Bodies and Beings from Magical Palestine (2014). Here, balloons each bearing a pencil-drawn eye that hovered over the entrance ceiling and an audio recording about a ghoul that entraps people's eyes and souls in a jar played in the entrance. A selection of drawings from the artist's oeuvre, some on paper others on canvas, were casually pinned onto a white wall in the room beyond the entrance. Some of the drawings are inscribed by a broken down lettering of the names of Palestinian haunted water wells. Abboud's depiction of the nude female body as neither sexual nor motherly, is in itself an important feminist statement since it is a significant departure from the standard Palestinian painterly tradition which has mostly equated the Palestinian female body to the 'land' and the concept of 'Palestine', and therefore limited it to the national patriarchal lexicons of fertility and honor that need protection against external threats.

Overall, the consistent use of visual, sonic and material folkloric traditions in Aboud's practice renders what is familiar unfamiliar, and allows these objects and subjects to bath within a well of mystery from which a proposal for a new aesthetic return to folklore emerges. Take for example, the newly commissioned Taleteller, Talisman, Tree and Stone, Enchanted Creature, Fragmented Bone. Presented within a slightly darkened room this mixed media installation is made up of a red display cabinet that outlines almost all walls of the room and contains different kinds of objects, postcards and drawings such figurines of lions, birds, unicorns as well as woodcarvings with human faces and transparent glass pieces that hint to the female body.

Expanding on the propositions in Abboud's exhibition, a panel discussion entitled Haunted Palestine – featuring Chiara De Cesari and Hamza As'ad – debated the documentation and historicization of Palestinian folklore with regards to ethnography and its instrumentalization within the Palestinian national movement and imagination. As'ad's presentation foregrounded a critique of Tawfiq Cannan's ethnographic practice – in turn contributing to an Orientalist image of Palestine – by arguing that Cannan's social class and urban upbringing projected a self-Orientalizing view of village folkloric traditions. Meanwhile, De Cesari's research stressed the emancipatory position offered to women by the instrumentalization and production of Palestinian textiles and hand stitching in the Palestinian national movement of the 1970s. This panel offered a much needed space to contemplate important questions: Has the Palestinian national movement and ethnographic traditions cornered Palestinian folklore into a space of self-pickling? Was the women's movement that emerged around textiles truly feminist and emancipatory or did it also place Palestinian folklore and women within a one-dimensional space? Khaldi concluded the panel by stating that Abboud's artwork might be one way of returning to folklore and celebrating its aesthetics and history without limiting it to the confines of ethnography.

The panel created a wonderful and critical synergy alongside the round table Under the Tree: Taxonomy, Empire and Reclaiming the Commons, staged as part of an exhibition curated by Nida Sinnokrot for the independent art initiative Sakia. Moderated by Shela Sheikh, who introduced a history of the colonial practice of botany, the first session included a presentation by Munir Fakher-Eldin, who reviewed the legal conundrums created by the laws and legacies of the British and Ottoman empires and the effects these policies had on the formulation of the current Israeli occupation of Palestine. Included in this panel was a presentation by Omar Tesdell, who provided a microscopic study of the challenges around the Palestinian lands in the West Bank marked as 'Area C'. The second part of the round table introduced artists whose practices reclaim contemporary resources such as file-sharing, seed banks and agricultural commons; Marcell Mars discussed his digital book scanner presented at Sakakini, which invited people to share their books as scans; Vivien Sansour discussed her Seed Bank, which is set up as a public library that catalogues, preserves and activates traditional knowledge around agricultural seeds in Palestine; and Beth Stryker talked about the CLUSTER initiative, which successfully negotiated a space for a communal public garden within Cairo city.

It is within these informative and nuanced spaces that 'return' as a theme and more importantly as an individual and collective practice, gained a conceptual expansion. As a whole, Qi2016's programmed activities within Ramallah called for a return to the landscape, its nature and wilderness with all of its be-wilderness and mysticisms through a fresh approach to the sonic, textual and visual traditions of Palestinian folklore, all the while insisting on the need for intimate spaces for connectivity within the public realm. This was grounded by a sober articulation of the problematic nature of Palestinian internal self-representations that have emerged as a result of the physical fragmentation imposed on the geography. Qalandiya International charted some beautiful possibilities in response: the raw seeds that will ripen in potential as this institutional collaboration forges forward beyond the logistics of co-ordination.