Reviews

Polyphonic Worlds

Contour Biennale 8

Curated by Natasha Ginwala, the eighth edition of the Contour Biennale proposes two themes separated by a colon that provokes the visitor to puzzle the relationship between them: Polyphonic Worlds: Justice as Medium. Both are outgrowths of the local history of Mechelen, the town just outside Brussels that hosts the Biennale. Polyphonic music played an important role in medieval Flemish culture, while from the fifteenth century Mechelen was the site of the Great Council, the highest court in the Burgundian Netherlands. From 11 March to 21 May, the exhibition presents practices of diverse provenance and sensibility that explore worldmaking and the law, often taking up research-based methodologies within a broadly documentary mode. Across six venues, only one of which is a white-cube gallery, twenty-five artists and collectives offer a speculative response as to how we might begin to live and think in ways adequate to the myriad crises that confront us today.

In an echo of the 'brain' of Documenta 13, Contour Biennale 8 offers an 'evidence room' on the ground floor of the Alderman's House, a historic venue located in the main city square. As with Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev's display on the rotunda of the Fridericianum, the materials assembled here provide insight into the exhibition's major strategies and themes. The legacy of colonialism and the ongoing imperative to decolonize are foundational. The collective Cooking Sections presents posters from the Empire Marketing Board, a British agency devoted to the promotion of trade in the 1920s and 1930s. The spurious exoticism of this propaganda is punctured by images of corporal punishment from the Belgian Congo, many of which were drawn from the Royal Museum of Central Africa in nearby Tervuren. Illuminated manuscripts of polyphonic music from the early sixteenth century offer an intriguing proposition as to how the exhibition conceives of itself and of the practice of art-making more generally: as a pluralistic encounter of multiple voices that coexist without resolving into a unity, with no medium, approach, or visual style dominating over others. Contour is, however, a biennial with a stated emphasis on the moving image; the inclusion here of J'ai huit ans (1961) – a masterpiece of militant cinema collaboratively realized by Yann Le Masson, Olga Polakoff and René Vautier in response to the Algerian War – signals the enduring importance of the political modernist tradition of filmmaking to many contemporary video works in the exhibition.

The notion of polyphony plays out most literally in Pedro Gómez-Egaña's The Moon Will Teach You (2017), an installation that transforms the attic of the House of the Great Salmon, a building that once belonged to the fish merchants' guild, into a creaking apparatus for the production of light and sound. Mostly, though, the resonance of this theme is metaphorical, evoking a desire to cast aside the violence of monological narratives – whether these pertain to Western hegemony, an individualist conception of creativity, or rationalist, anthropocentric approaches to worldly inhabitation. On this last front, the exhibition's embrace of stylistic and conceptual heterogeneity is visible in an exemplary way, traversing the beautiful lyricism of Beatriz Santiago Muñoz's films of her native Puerto Rico, Ho Tzu Nyen's six-hour CGI bestiary NO MAN II (2017), Agency's presentation of 'things' from their list of items that refuse the split between nature and culture (for example, selfies taken by a monkey), and Susanne M. Winterling's highly theorized yet phenomenologically disappointing digital renderings of bioluminescent organisms, Glistening Troubles (2017).

Mechelen's status as the historical site of the Great Council intimately connects the town to the development of jurisprudence and the rational principles of European law, and many works in Contour Biennale 8 reflect on or document legal processes. Upon entering the Garage, the starting point of the exhibition, one comes immediately to Ana Torfs' Anatomy (2006), a multimedia reimagining of testimonies involved in the prosecution of the murders of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg; just adjacent, the collective Council present lithographs that will form part of their nascent publication The Against Nature Journal, devoted to an exploration of how the concept of 'nature' is used to criminalize sexual practices in diverse countries around the world.

This interest continues in Lawrence Abu Hamdan's The recovered manifesto of Wissan [inaudible] (2016) and Eric Baudelaire's Also Known as Jihadi (2017), both located in the sixteenth-century Court of Savoy, a palace that once served as the seat of the Great Council and now houses the lower civil and criminal courts. It risks overdetermination to place two artworks engaging explicitly with the juridical system in such a site, yet the gesture succeeds as both are given adequate space within an architecture amenable to their presentation – a privilege not enjoyed by all works in the Alderman's House and the Garage. In the baroque gardens outside, Abu Hamdan weaves cassette tape around a tree, recalling a practice aimed at repelling birds and insects. This sculptural intervention is joined by audio recovered from a tape found on one such tree in Lebanon's Chouf Mountains, in which a man discusses the concept of Taqiyya, the Islamic juridical notion by which it is permissible to lie or deny one's faith in instances that might otherwise lead to persecution. The work probes the relationships between truth, testimony and the materiality of recording, while mingling with the ambient noise of the city and garden so as to induce a heightened auditory attunement to one's surroundings.

Baudelaire's exceptionally strong feature film follows the story of Abdel Aziz Mekki, currently incarcerated in France for allegedly travelling to Syria to fight as a jihadi. Its title signals a debt to Masao Adachi's 1969 A.K.A. Serial Killer, in which the filmmaker put into practice his notion of fûkeiron, or landscape theory, which posits that social forces become visible in the built environment. And yet to deem the film a remake would be too simple. Baudelaire takes up Adachi's vocabulary of extended long shots of locations traversed by the titular figure, but also questions what is revealed, if anything, by such observation. Interspersed with these landscapes are documents from the legal proceedings against Mekki; these offer a second apparatus of knowledge production, but one that possesses its own limits to understanding. Also Known as Jihadi opts for banality, aftermath, and bureaucracy to treat a story typically sensationalized, powerfully intervening into a system of profoundly Islamophobic media representations with a plea for the ethical power of opacity and unknowing. Moreover, by asserting a commitment to the sober lens-based capture of actuality whilst subverting the epistemological claims historically associated with it, the film makes an important case for the urgency of a reconceived observational mode of documentary. It offers a welcome gesture at a time when the ubiquity of 'post-truth' paranoia demands that we cast doubt on the contemporary viability of a strategy often championed within the artistic context, the blurring of reality and fiction.

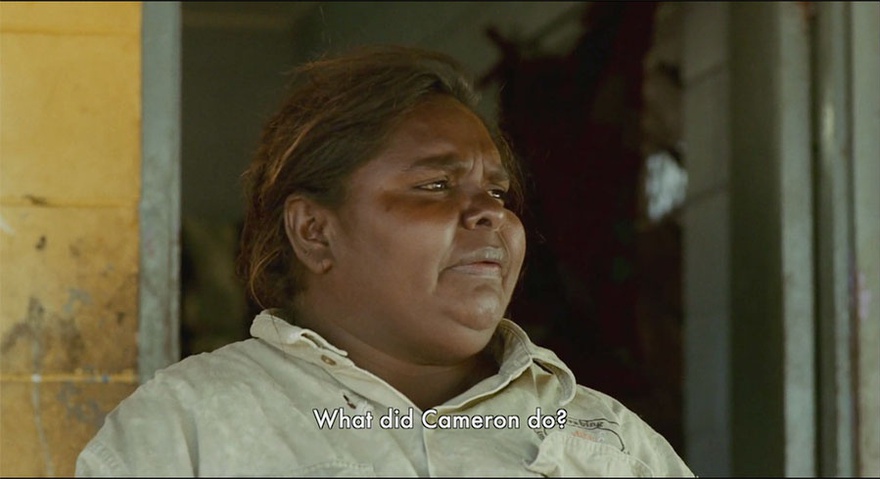

Ginwala's curatorial statements do not make a distinction between justice and the law, yet key works in the exhibition suggest the usefulness of doing so. Whereas law refers to a system of jurisprudence mandated by a community or nation-state and its subsequent enactment in theatres of power, justice might be understood as a call that goes beyond the law, emerging especially when faced with its inadequacy. It is a claim for radical reparation that remains forever in a state of suspended virtuality; it is always to-come. Several contributions seize on moments when the law sanctions the unjust, notably in situations of (neo-)colonialist extraction and expropriation. In the Alderman's House, Otobong Nkanga's Reflections of a Raw Green Crown (2015) turns to the material of copper to explore the linked economies Africa and Europe, while in the House of Great Salmon, the Karrabing Film Collective's The Stealing C*nt$ (2017) takes up participatory and performative ethnography to call attention to the toxicity of settler colonialism in Australia. Through the story of four indigenous men's confrontation with miners and police after stealing two cases of beer on poisoned land, the film questions the law's selective protections and its differential definitions of 'theft', levying a demand for justice.

In a cavernous industrial warehouse located a short walk from Mechelen's centre, one finds projections by Adelita Husni-Bey, Pallavi Paul, Basir Mahmood, and Filipa César and Louis Henderson. César and Henderson's Sunstone (2017) stands out as a special highlight. In one regard, the film is a portrait of Roque Pina, the keeper of the lighthouse at Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point of continental Europe. He speaks in voiceover throughout, of his job and of his complex inheritance as the son of a Cape Verdean father who fought for the Portuguese. He asserts the need for a philosopher of the lighthouse. César and Henderson respond to this call: through and beyond the portrait of Pina, Sunstone explores the optical metaphors of Enlightenment rationality through two lens-based technologies, the lighthouse and the film camera, at a time when they are being displaced by the algorithmic forms of GPS and CGI, respectively. The lighthouse becomes a figure for an ambivalent heritage of discovery and orientation, notions that are as epistemological as they are territorial. César and Henderson layer computer renderings over gorgeous 16mm cinematography, reflecting on the role of each within larger epistemic shifts that move us from the horizontality of the lighthouse's beacon over the ocean to the verticality of satellite positioning systems, from visuality to code. Taking its name from a crystal used for ocean navigation in centuries past, the film proposes a multimedia archaeology of attempts to master the world – through conceptualization and geographical conquest alike – and insists that these form a history that must be thought in terms of both continuities and ruptures.

While avoiding any didacticism, Sunstone potently articulates questions that animate Contour Biennale 8 as a whole. How do we negotiate concepts like truth, observation, and rationality today, when we acknowledge the violence of Enlightenment thought but also see the dangers of retreating into myth, subjectivism, and irrationalism? From what position do we speak of and gaze on others? And how can we transform scenes of domination into practices of care? There are no singular or easy answers, but from within the polyphony of Contour Biennale 8, sketches of other, better ways of worldmaking appear on the horizon.