Reviews

Curated Conversations

HIWAR | Conversations in Amman

HIWAR | Conversations in Amman is organized by Darat Al Funun as a residencies, exhibition and talks program to celebrate 25 years of support for the arts. The program began with the first residency in September 2013 and was followed by the second residency in October 2013. The residencies were designed to create a space of exchange and dynamic interaction between artists from the margins (or the periphery, the Global South, the former Third World).[1] They came from cities as diverse as Beirut, Cairo, Cuzco, Hanoi, Istanbul, Johannesburg, Luanda, Manila, Mumbai, Ramallah, Recife and São Paolo. During each residency, presentations and conversations regarding artistic practice and methodology, socio-political influences, commercial art structures and art education were held between the Curator, Adriano Pedrosa, the Artistic Director of Darat Al Funun, Eline van der Vlist and the artists in residence. These conversations culminated in an exhibition that utilized the extensive grounds and spaces of Darat Al Funun, a compound of houses built by a Jordanian, a Lebanese, a Palestinian and a Syrian, including: Blue House, Dar Khalid, Main Building, Print Studios, Ghorfa, The Lab, Headquarters and Beit al Beiruti.

The exhibition opened on 9 November 2013 and continues until April 2014. It displays work from the 14 artists in residence[2] alongside works from 15 artists in The Khalid Shoman Collection.[3] Overall, the connection between the artists in residence work and those from the Khalid Shoman Collection appears to be minimal, and with little text provided the viewer is left to draw their own conclusions. That being said, a correlation can be observed between two works in particular. Installed in the Main Building is Akram Zaatari's Saida June 6, 1982 (1982-2006); a large-scale composite image, video and sound presentation that is both an account and a recreation of Israel's air invasion into Lebanon in 1982. The blue sky against which explosions are depicted in the work, bear similarities to artist in residence Nguyên Phuong Linh's Edith's eyes. Chapter 1: Sanctified Clouds (2013), presented in the Headquarters. Linh's cluster of blue print explosion images extends to the uppermost part of the wall as though recalling the same blue sky in Zaatari's work. The title of Linh's work brings to mind A Song for Peace and Honour – a poem by British author Edith Nesbit in which she speaks of, 'The priceless pearl of peace – peace plucked from out the very heart of war, through the long agony of strenuous years, made pure by blood and sanctified by tears…'[4] Here, at the intersection of Zaatari, Linh and Nesbit's work is perhaps the emergence of a dialectic, in which art negotiates with war as a matrix of peace.

Also in the Headquarters is Daniela Ortiz's work – an exploration of the tension created in nations with active limits on expression. Stacked in the center of a room are 1000 copies of a black book, a compilation of 31 Censored Issues (2013). On each page text is crossed out with a thick black marker, rendering the text illegible and leaving images without context. That viewers are invited to take copies produces a certain irony, given that what is being distributed is censored material, devoid of any reference as to why or when these issues were censored. Without even an indication of where these issues took place and no record of authorship, Ortiz's installation becomes frustration, performed.

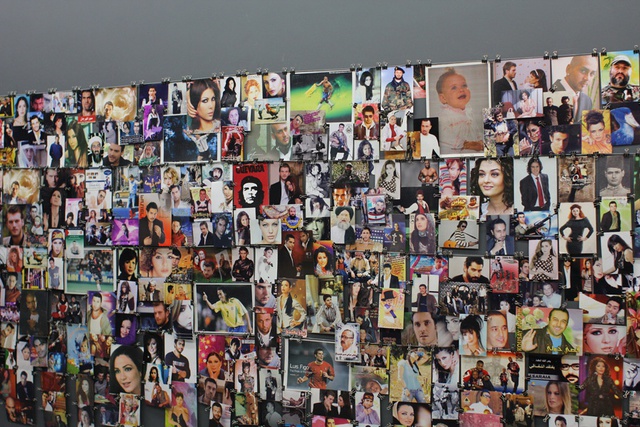

Ortiz's circulation of censored issues is not entirely dissimilar to the distribution of images recorded in Shuruq Harb's video and photo installation The Keeper (2013). The work presents images from an archive of one Mustafa, a young entrepreneur who used to sell images of pop culture, celebrities and politicians on the streets of Ramallah. When Mustafa's predecessors created the business in 1998 they only sold religious pictures and landscape images. But over the years and with increasing demand the emphasis shifted to pictures of famous actors and musicians. Although not illegal, these images are haram (sinful); as such, they are religiously censored. Mustafa left this business to find a more morally acceptable way of making a living, and Harb acquired the archive.

Meanwhile, Asunción Molinos Gordo investigated the ethics of work in The Peasant has a Hoe (2013). Her deconstructed notebook reveals pages of repeated text – syntactic exercises common in Jordan and Egypt to improve calligraphy and grammar. The peasant farmer is the customary protagonist for these didactic exercises and Molinos uses this tradition to create a written narrative on the exploitation of peasant farmers whose land and livelihood have been lost to the privatization of commodities and the influx of imported crops. Like her repeated lines, displacement becomes cyclic as these landless farmers move to newly built urban areas and are employed as construction workers.[5] Alternatively, they join the army and are sent to quell the same peasant protests they once participated in.

Landlessness and deterritorializaton is also explored in Saba Innab's collection of work in the Main House, How to Build Without Land (2011-ongoing). As the lines on her aerial photos of the Nahr el Bared Palestinian refugee camp extend onto the white walls with handwritten details of migration and flux, her unsettling questions are: 'How do we build temporariness when it is mutating constantly into a permanent state? What becomes of building and dwelling between the imagined and the real and between the temporary and the permanent?' Bisan Abu-Eisheh concretizes these questions in his Moving Homes (2013) installation in Ghorfa. His metal sculpture of the temporary homes used by Palestinian refugees is mounted on four gas cylinders, commonly used to transport the structures through the camps. Abu-Eisheh's structure fills the empty space of the building and is a psychological reminder of the constrictions of landlessness – the boundaries of displacement. Innab suggests that the impossibility of dwelling is so acute it can only be undone in death. This, perhaps, was a truth realized by the construction workers discussed in Clara Ianni's Free Form (2013) – a two-channel video on the murders and deaths of workers during the construction of Brasilia in 1959. The passive defensiveness of the reports given by Brasilia's architect, Oscar Niemeyer and urban planner, Lucio Costa are as uncomfortable as they are revealing. For them, the workers' deaths were an incidental and an inevitable part of building.

In Beit Al Beruti, fellow Brazilian artist Jonathas de Andrade created an installation entitled Procurando Jesus (Looking for Jesus) (2013). Mobilizing Brazil's Catholic heritage, this was a search to discover what Jesus would have really looked like in a region that could never have produced the blonde-haired and blue-eyed stereotype we are so familiar with. The humour with which Andrade presented the subject masked the experiential challenges of asking a conservative Jordanian public what they thought Jesus could have looked like, or possibly where he could be found. His investigation resulted in headshots of 20 possible candidates. Viewers are invited to cast votes for their favourite Jesus by eating a date from the suspended lantern and putting the seed in a ballot box.

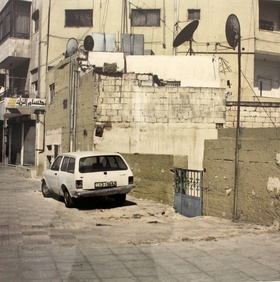

The passage of geo-cultural exchanges continues in the Main Building with Thabiso Sekgala's Social Landscape (2012) and Running (2013), two series of photographic scenes from Johannesburg and Amman facing each other in apparent dialogue. The visual similarity between the two cities is remarkable but also surprisingly familiar, as if the connection between them was obvious.

Sekgala's metaphorical conversation between two cities on the margins was followed (on the second day of the exhibition) by a discussion with the curator of HIWAR, Adriano Pedrosa, Artistic Director of Darat Al Funun, Eline van der Vlist and international curators Bisi Silva, Pablo Leon de la Barra, Suha Shoman and Vali Mahlouji. As curators working at the peripheries, they were invited to discuss the largely unexplored terrain of connections and communications within the Global South. Points were raised on the importance of moving away from a Euro-American centre, (which, by definition, marginalizes everywhere else) and creating new geo-cultural loci that put countries like Jordan, Brazil and Nigeria at the core of their art narratives. Many of the exhibited artists were present at this talk but interestingly they were not invited to speak on the panel as co-participants in this discourse. Listening to each curator probe the issues around dewesternization and South-South dialogue, parallel questions emerged: What is the status of the artist in such a discussion? Is their limited involvement meant to indicate that they are primarily concerned with artistic practice and not with the global power dynamics that shape their experience? HIWAR had brought these artists together to converse but in their silence at this panel, it felt like an opportunity had been missed and the artists were twice marginalized. This begs the question: in a conversation at the margins, can the artist speak?

[1] HIWAR curator, Adriano Pedrosa, provided this definition of the term 'margins' in the HIWAR | Conversations in Amman booklet. Other curators contested its usage and meaning during the 'Conversations at the margins' panel discussion.

[2] Artists in residence: Asli Çavuşoğlu, Asunción Molinos Gordo, Bisan Abu-Eisheh, Clara Ianni, Daniela Ortiz, Hemali Bhuta, Jonathas de Andrade, Kiluanji Kia Henda, Maria Taniguchi, Nguyên Phuong Linh, Rayyane Tabet, Saba Innab, Shuruq Harb, Thabiso Sekgala

[3] Artists from the Khalid Shoman Foudation: Abdul Hay Mosallam, Ahlam Shibi, Ahmad Nawash, Akram Zaatari, Amal Kenawy, Emily Jacir, Etel Adnan, Fahrelnissa Zeid, Hrair Sarkissian, Mona Hatoum, Mona Saudi, Mounir Fatmi, Nicola Saig, Rachid Koraïchi, Walid Raad

[4] Edith Nesbit, 'A Song for Peace and Honour,' Songs of Love and Empire. Archibald Constable & Co.,, Westminster, 1898.

[5] Asunción discussed this on her website, AsuncionMolinos.com, as part of her El Matam El Mish-Masery project.