Essays

Notes on Performative Urbanism

An Emergent Design Approach to the Gulf

The Gulf is home to some of the world's most controversial settlements. Historically, urbanizing large areas and introducing a new aesthetic in architecture is very much inherent in the creation of the contemporary 'Arab city'. The traditional Islamic horizontal urban pattern and its direct relation to land and water have shifted to vertical and global networks of trading, tourism, fantasy, Orientalism and investment in generating new fractal cities. A canvas filled with nomadic crossroads, north-south immigration patterns and east-west trading axes bisect a tabula rasa of vast desert and extremely hot climates. The well-documented discovery and exploitation of oil in the region has also provided a complex matrix of potential interconnectivities. These post-colonial cities of the late twentieth century have grown out of new technologies, telecommunications and mega infrastructures that have brought about dramatic morphological and ecological changes: a fusion of reality and computer-generated imagery makes the banal landscape look evocative and artificial. This partial and virtual condition gives rise to fantasy and the promise of the future.

Dubai's early urbanism

Since the 1950s, Dubai embraced modernity in architecture. This approach was initiated by Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, who ruled Dubai from 1958 until 1990. His vision was to have a significant impact on how the post-oil emerging Gulf city developed: through master plans and towers. The chronicle of Dubai's dramatic embrace of modernity since the 1960s is prophetic of the manner the city was to be developed in the twenty-first century. In 1959 Sheikh Rashid commissioned John Harris, an architect from the UK as Dubai's first town planner. Harris' first Master Plan of Dubai addressed the basics for a rapid expansion: a road system and directions for growth across the desert. In 1972, Sheikh Rashid commissioned John Harris to design the World Trade Centre tower for Dubai. This was modelled on New York's World Trade Centre. In 1975, the construction of the Dubai World Trade Centre began. The building was 39 stories and the tallest in the Middle East. In a single and unpredictable moment of history an office tower made a modern city, turning it away from its old fishing port towards the future and the west. The Gulf city was finally born.

Metropolitan fantasy

The Gulf city presents itself as a form of escapism and its constructed imagery reaffirms this impression. Visual representations and images depict glamorous and exotic scenes of settlements in deserts and islands, at times familiar, but combined with escapism and daring lifestyle. The city is colonized with huge advertising boards, prophetically projecting a glorious future. The billboard articulately captures the power of the commodified image. It sells not just a product but also a lifestyle. One has to conform and subscribe to the predetermined model; the possibility of any active participation in the construction of the lived world has been all but erased.

What is amazing is that the city is evolving as a precise replica of its imagery and scaled models. This fetishization and obsession to represent the city through images generates an uncritical acceptance of these images. This is an architecture of persuasion. 'The spectacle does not realize philosophy,' as Guy Debord observes, 'it philosophizes reality. The concrete life of everyone has been degraded into a speculative universe'. In a culture of aestheticization, seduction is all that is left.

The city thrives on its own self-built momentum. It becomes a 'site'. What has been created here is an irresistible attraction: a safe, international city-state with completely free enterprise and all the pleasures of life, located next to the largest reserves of the world's most vital strategic commodity – oil. The Gulf city represents the true twenty-first century city: an assemblage of scattered vertical and other scaleless developments in empty plots with no vision or manifesto.

Orientalism

Despite waves of western-style modernizations, the visitor of the Gulf city still expects to find it Islamic. Cities of the Near East and North Africa were often collapsed into an imaginary 'Orient'. These marginalized perceptions have become monumentalized, reconstructed experiences and icons for the tourists. Gulf cities manifest the contemporary interpretation of Orientalism: sensual, spectacular, artificial, subliminal and, above all, contemporary and global. The contemporary expo of Orientalism in the west is now taken over by developers promoting a western lifestyle in the oriental settings, representing Middle Eastern culture as haute couture in exclusive towers of wealth, or gardens in exotic islands. The region is now manufacturing Oriental images for the west. Architecture and mega structures of modernism are built with Islamic patterns and geometries. Urbanism takes the form of a revised Garden City, or rather a garden with city parts and buildings. One can contrast the west's preoccupation with figuration with the east's fascination for abstraction. Twenty-first century Orientalism is not the depiction of Middle East in paintings for the aristocracy in the form of colonial acquisition, but mass tourism and the postcolonial power of internationalization and global transmutations.

Constructed leisure-lands

In Dubai there is little difference between holiday accommodation and housing. Architectural programmes are becoming fused and undifferentiated. The morphology of the landscape and seascape is becoming fabricated to the point that it may soon be difficult to differentiate between the natural and the constructed. This constructed landscape, like a stage set, provides edited scenes of adventure and entertainment. The city of Dubai sprawls out like an exponent of an algorithmically evolving pattern: a fractal architecture with forms of increased perimeter and endless topological variations, as two-dimensional patterns, allowing very little for three-dimensional variety. Increasingly, this kind of contemporary architecture and urban staged and edited scenes that stimulate mass tourism has to be photogenic; buildings should now look striking in a sequence of rapid cuts or to stand out in a static shot as backdrops. No matter which part of the world, whenever architecture is built from nothingness, it seems to be fond of a universal language of spectacle and the exoticism of the new. Inevitably, this has led to concentrated tourist infrastructures and mega-structure complexes (hotels, apartments, malls, cinemas, expos etc.), which are clustered together. In this sense, architecture and landscape are part of a single system, characterized by stratification and controlled spatial experiences.

Accelerated urbanism

While most western metropolitan centres at the beginning of the twenty-first century have reached a state of saturation, developing economies of the world (notably in Asia and the Middle East) are emerging as new models of architecture and urbanism. In the Gulf, the discovery and exploitation of oil in the mid-twentieth century triggered the development of fast urban developments set against vast and empty quarters of desert in arid climates. Furthermore, the vision and determination of the rulers in these regions to modernize and attract foreign investment has created a phenomenal speculative real estate enterprise. Custom-made architecture for business, tourism and consumption as well as infrastructural projects, within a period of few decades, have transformed and reconstructed the main coastal towns in this region; from sleepy, hassle-free, small fishing towns to high-tech end destinations.

The syndrome of an 'emerging new city' like New York a century ago, attracts a large influx of migrants in search of a new future. This inevitably creates a new demographic hybridization and inconsistent social patterns. Building developments in Dubai relate more to the global network of trends, finance and trade and other similar operations, than to their locality and community. They are alienated from their geographic location and community. Since the landscape is always barren, anything goes and anything is new. Dubai has no density. If there is, it is by virtue of proximity rather than layering. So buildings are detached, isolated, gated, and this paradoxically becomes a haven for upper class buyers, seeking to distance their lifestyles in exclusive retreats. The city has definitely ceased to be a place: instead, it has become a condition. Perhaps the city has even lost its site: it tends to be everywhere and nowhere. Almost overnight, the city has become a juxtaposition of barren deserts and twenty-first century skyscrapers at extravagantly optimistic construction sites. The city is a large construction site, preparing itself for the incoming international nomads: new settlers, labourers, consultants, in-transit business travellers and tourists, all seeking better salaries. This is an accelerated urbanism unlike any other; it is immediate in its pictorial seduction. The urbanization process is streamline, effective and fast. Buying architecture is like buying a product. Living in it is like acquiring any lifestyle you can afford. What is interesting is that this is a new city caught up in unprecedented conditions of this century: globalization, accelerated technologies of imaging and communication, abundance of investment and mass tourism.

Transmitted Imagery, Tourism and Constructed Leisure-lands

As the technology in the image production of virtual architecture becomes sophisticated and persuasive, it can also now be transmitted across the globe instantaneously. This is the future new state of world urbanism – prescriptive, full of visual dramatization and an advertisement of 'total lifestyle experiences'. The panoramic imagery of artificial coastlines is broadcasted around the world, as a new type of 'satellite urbanism'. Google Earth aerial reconnaissance imagery turns into spectacle and 'telegenic' fantasy addressing and inviting the prospective tourist. At the same time on the ground, developers turn Dubai into a postcard portrait city. Panoramas, extended perspectival vistas and imagery of speculative projects are used as representations to give rise to the exciting prospect and promise of future lifestyles.

Dubai thrives on consumerism. This is a city that owes its early survival and its current momentum to trading. Everything points to consumption. This turns everything into a theme park seeking to sell the arabesque, tropical, oriental and international; all in one. Tourism and shopping are the new past times of the middle classes. Dubai is a constructed leisure land, a true Dubailand. It is like a diagram of staged scenery and mechanisms of a 'good time'.

Climatic urbanism

Any discussion of architecture, urbanism or culture in the Gulf should refer to the region's extreme climate and arid ecology. The ability inherited by the Bedouins to survive at high temperatures with limited resources, something unimaginable to the west, led to techniques and strategies of responding to both climate and landscape. They developed an ability and intelligence in navigating, settling and adapting to climatic changes. A culture that has the ability to adapt and transform is evident today in the Gulf as well. Such conditions of a mobilized population encouraged a way of living that was dependent on environmental parameters.

A typology grew out of the early small settlements that remained almost unchanged until the discovery of oil and the emergence of modernity in the Gulf from the 1950s to 1970s. This modern condition was not as pure as its European counterpart. It brought something new: the fusion of western modernity of clarity and transparency with local and oriental mystique of opacity and intensity of light.

Reclaiming large and arid areas of desert and turning them into liveable neighbourhoods is an expensive enterprise both in terms of infrastructure and physical transformation. The combination of fast cities on limited land produced a Manhattan-like effect at the end of the twentieth century: land division, high-rise building planning and curtain walls. As this rush to build reached its peak, the building technology of the glass façade in the region remained outdated. Buildings looked identical. Any discourse on environmental performance and innovation did not exist. The midday heat during summer in the Gulf is a condition that defines the critical threshold of building inhabitation. This extreme atmospheric temperature of 45 degrees centigrade and 80 per cent humidity outside is in complete contrast with the desired comfort-zone of cool, well serviced and dust free interiors. This extreme threshold may be the single most challenging dilemma of architecture of the region. All research and practice of energy performative design and technology are tested. The thermal response of any building enclosure in the Gulf can almost alone determine the type of architecture in the region. It is in effect autopoietic.

Until recently, westernization was interpreted as the only form of modernization. Contemporary processes can now unleash the potential of the Arab city. Emergent practices of digital and dynamic processes and topological modelling are now capable of incorporating a new language in architecture that can reconnect urbanism to modern life with environmental specificity and culture. More importantly, it can make context and any idiosyncrasies found in a locality more relevant. This is a new form of modernization. Instead of celebrating the uniqueness – and at times the nostalgia – of the architectural object, performative urbanism focuses on how the object (material tectonics), the process of production (programmatic iterations) and local behaviour (contextual anomalies) can become culturally relevant. The generation of form can now relate to materiality and follows a process in which geometry, coded with material behaviour, becomes responsive to fields of influence, physical forces and environmental dynamics. It can be local.

Parametric modelling, commonly used in the automotive and aerospace industries, has recently been integrated in the process of construction. The capacity to design small repeatable components and apply them to a larger governing surface geometry is one area of parametric modelling that has unlimited design and environmentally sustainable potentials. This two-level modelling control, of component and overall surface, can allow the exploration of new types of form generation subject to parametric constraint. In terms of a building enclosure designing a parametric system of facades using animated adaptability, iterations and geometric configurations allows modelling to control climatic resistance but also flexibility.

Environmental and ecological considerations can now, for the first time, challenge the mere iconic and define a new performative and material approach reminiscent of the Islamic city that was layered and predominantly undefined. This modelling machine creates a new abstraction and a new hybrid condition. The emphasis of the exploration is on complexity and efficiency. In effect digital processes and technology are shaping the future of cities. After all, we are all nomads inhabiting an image.

Studio Research and Urban Mappings

Transformation is the key operation of contemporary urban culture. Cities are in constant flux. They require re-structuring and transformation on almost every level. Regardless of the scale and nature of these changes, their impact on its citizens are largely unpredictable and their repercussions unknown. This climate of uncertainty is intriguing; within it even the smallest tweaks have an impact. This is a new type of urbanism: the manipulation of the urban fabric by inserting structures that trigger change, provoke and demand response.

Urban centres in the Gulf are 'cities from zero' with a metropolitan character that is currently 'in the making'. This requires participants to focus, observe and analyse this unique urbanism. The studio investigates the development of design through explorations of formal and material systems and their association with urban networks and new programmes. These design systems and processes are developed through a series of visual and material research, which requires conceptual and technical rigour. The ambition of the project is to invent new formal languages and make proposals engaged with the changing global metropolis. The studio challenges the current practice of architecture in the region and makes alternative proposals for the city. By adopting contemporary practices, such as modelling in physical and digital form, the work of the studio attempts to go beyond some of the preconceived boundaries of architecture, notably that of the traditional sequence of site, programme and proposal. Contemporary architectural processes are capable of accommodating transformation, adaptation, and deterioration as well as unpredictable, inconsistent or changeable events and conditions. Contemporary Computer Aided Design (CCAD), such as mapping and modelling, may now incorporate advanced techniques of parametric geometry, topological variations, algorithmic design, animation, scripting, expressions and dynamics in order to simulate, predict and generate spatial conditions which would have been impossible to invent using traditional tools. Architectural design is an adaptive process, which is engaged in a continuous transformation. The sequence of operations will start from a small scale and extend to a larger one.

Studio work

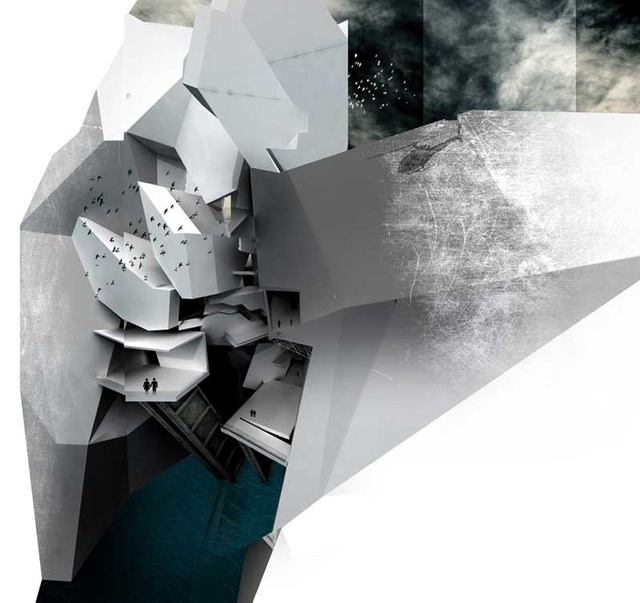

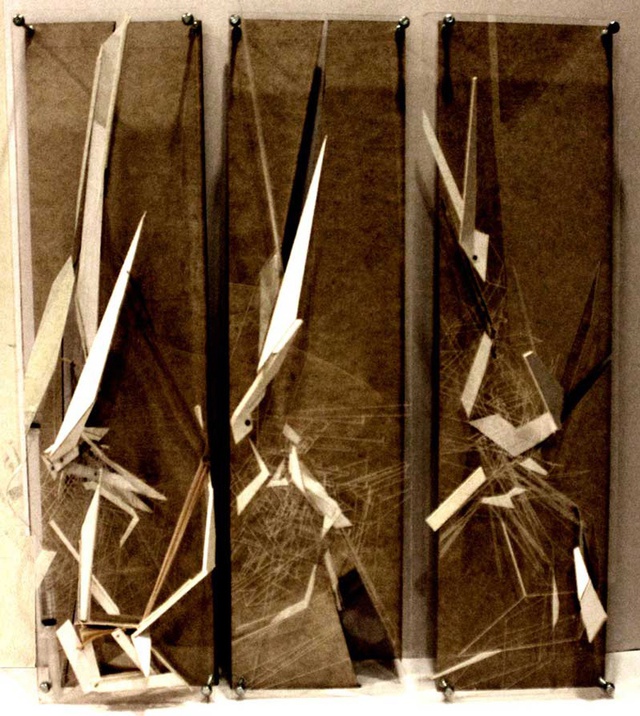

Design is an autonomous process and an incubator of ideas. The sequence of operations in the process follows a logical structure: concept, collages, machine, physical modelling, digital modelling and scripting (programme and variations), systems and iteration (scale and adaptation to a site), test fabrication, representation (architectural drawings such as plans and sections extracted from complex 3D digital models) and ultimately construction. It is a sequence of continuous and rigorous transformation. The studio progresses in a series of stages, with each stage corresponding to an increase in complexity, scope and scale. The quality of both the process and the outcome are equally important.

By adopting contemporary practices, such as modelling in physical and digital form, the work of the studio attempts to go beyond some of the preconceived limitations of architecture, notably that of the traditional sequence of site, programme and solution. We like the incomplete, raw, crude, unpolished and endless potentialities of architecture; atmospheric rather than glossy. The studio is interested in questioning what architecture might be – not what architecture is already understood to be, or how it is already created and practised.

During the process of design, an architectural language becomes gradually embedded, first in the early explorations, and then manifested in drawings, models and animations. This is ultimately brought together with the necessary demands for use, functionality and occupation. At the end of the process all architecture and its formal expression has to be beautiful. The studio employs techniques, logical and intuitive, analogue and digital to represent the project. This generates a system of tectonics and structures, which are spatial and formal.

In recent years the studio projects have developed an architecture that is built up by many different strata of applied scientific knowledge, software-based morphologies, micro-worlds and intelligent environments such a physical forces, gravity, fluid dynamics, particles and temperature. This is a type of performative application rather than aesthetic composition. Dynamics, topology and systems then become tools that pertain in a large degree to the control and manipulations of formal strategies. Context should not be reduced only to the facades and heights of surrounding buildings or to random nearby urban activities. Good architects have the ability to exclude rather than include and focus on a singular and significant idea. Contextualizing a project is a complex process of discovering and balancing visible and invisible forces and parameters; it not only about fitting into a surrounding. A project should give something significant back to the site and the city and, in most cases, it can 'make' the site, if the site has nothing to offer.

The studio is organized like an experimental-research effort in the field of architecture rather than a typical academic studio. Within this framework each student has the opportunity for independent research. Each proposal is identified by the singularity of the idea and intention. Young graduates of architecture in the Arab world have tremendous potential. There is no need to look at the western model alone. The environmental, cultural and material culture of the Middle East is so rich that it can be reinterpreted and stand-alone.

Studios should work within the context of the post-Middle Eastern city at the beginning of the twenty-first century as a metabolic instrument and develop proposals that trace a subliminal and imaginary condition both in urban, landscape or desert areas. The idea of 'newness' in architecture should be used at various levels to achieve innovative architectural propositions. As such, the role of educators of architecture in the Arab world is complex: teach the basics; understand the city and engage with it (not only historically); deal with hybrid and contradictory models; and discover unique material processes as well as using digital media in the process. The emerging generation of architects in the region is capable of making a significant impact.