Essays

Mobile Maghrebs

Contemporary Cinema from North Africa

As he looks out over the port of Algiers, Kamel, the young, unemployed protagonist of Tariq Teguia's Rome oula antuma (Rome Rather than You) (2006), sketches out his worldview for his girlfriend Zina: "Marseille, Allah, Marseille calls me. Marseille, in the kingdom of France; we haven't yet finished with them. Barcelona, Muslim prayers were said there. Naples, they're our paternal uncles." Calling upon a long and complex history of relations between Southern Europe and North Africa to unsettle contemporary national boundaries, Kamel then invokes an America ruled by a just king, where all are free from persecution, anachronistically assimilating an America of presumably open borders with a medieval history during which Europe and Islam were intertwined. He concludes with the pronouncement: 'Australia, ah Australia' – the destination he hopes to reach. As Kamel speaks, the camera stays fixed in mid-close-up of Kamel and Zina, who stand on a nondescript metal bridge, with train tracks, a highway, parking lots, a concrete building, cranes and distant cargo ships visible behind them. When Zina skeptically inquires what Kamel plans to do in an Australia populated by sheep and kangaroos, questioning whether he will be able to leave behind his 'beloved neighborhood', this bleak industrial mid 1990s backdrop appears not as a point of departure for new futures, but rather as a deteriorating, vista-obscuring present. In response to her query, Kamel, proclaims: 'long live globalization' – an ironic twist on the chant 'long live Algeria', which was popularized the world over by the Battle of Algiers (Pontecorvo, 1967). A black screen with white writing in Arabic replaces the image and belies his words:

من يتجول بحدوده في ارض الاخر يمارس الحرب

[He who roams with his boundaries in the land of the other practices war.][1]

When the image returns, Zina matter-of-factly declares, 'Money and goods, that's what travels, not men,' while Kamel insists: '"Arab" means those on the move,' underscoring the etymology of the word.[2] 'Arab means those who are denied entry', rejoins Zina, highlighting the tenaciousness of late-twentieth century national and identitarian borders that separate the Global North from the Arab Global South

In popular parlance, Kamel is a harraga (from the Arabic حراقة), or 'burner', a term upon which news media in North Africa and southern Europe have eagerly seized to describe the crush of undocumented immigrants from Africa. Not to be conflated with the acts of self-immolation that came forcefully, if briefly, into the global spotlight when Mohamed Bouazizi set himself aflame and touched off the protests of the Arab Spring, the term harraga (often transcribed as haraga) derives from some clandestine immigrants' practice of burning their identity papers in an effort to mask their origins.[3] While there are many ways to 'burn'-obtaining false travel documents, as Kamel seeks to do, destroying one's identity papers after a successful arrival in a foreign land, leaving them behind or throwing them overboard during a secret, and dangerous, crossing of the Mediterranean or Sahara – such immigrants are commonly understood to be breaking ties to their pasts, burning their bridges, so to speak.

Yet, Kamel's statements indicate quite the opposite: that the act of travelling is, in fact, one of many possible reclamations of a mobile heritage. His words, distant though they may seem from contemporary geopolitical realities, articulate a refusal to renounce any part, or iteration, of the pasts that converge in late post-independence Algeria. What he seeks to 'burn' are those late twentieth-century maps that offer him only limited and limiting trajectories by fixing his identity as threat and his presence as illegal. For her part, Zina seems to practice a different kind of border war, one grounded in more recent third-worldist politics and challenging the identities and values attached to certain locations on the world map. Like all cartographers, the two young people in Teguia's film map the world from the perspective of their own interests ; they do so, however, in full cognizance that dominant worldviews relegate them to the margins.

Recent Maghrebi film, too, has 'burned' – overtly and less overtly breaking with dominant national discourses of identity and progress, whether social realist, third cinema, or commercial – as increasing numbers of Algerian, Moroccan, and Tunisian filmmakers seek out new perspectives, influences, affiliations, and audiences. Like the harraga they often feature, these films reject nothing, whether genre, movement, history, theme, or politics, their films instead probing the trajectories mapped out for 'Maghrebi' cinema by individual nations, international film festivals, and formulations of Middle Eastern, African, world or global cinemas. Employing a medium created of and defined by motion so as to probe the immobilizing and mobilizing effects of particular maps of the region and its cinema, these filmmakers today put the mobility of the region on the map, or rather, maps. Thinking about this through recent works by Teguia, Nacer Khemir, and Faouzi Bensaïdi, this essay will trace how Maghrebi film troubles contemporary efforts to map the Northern Rim of Africa not only as a self contained zone bounded by the Mediterranean Sea on the North and the Sahara Desert on the South, but also as a zone of containment for flows of people and ideas from the south and east.

Peripatetic Sites

In Rome oula antuma (Rome Rather than You), Kamel and Zina continue their repartee on the bridge, Kamel reciting in classical Arabic an abridged version of the Emma Lazarus poem inscribed on the base of the Statue of Liberty, and Zina (mis) citing Kafka's menacing characterization of that statue, before abruptly asking just how many people the ship visible in the distance can carry.[4] Giddily, Kamel replies that the Algerian population in its entirety will crowd aboard: a statement that conjures a scene of hyperbolic mobility, startling in its inclusivity and unmooring of national identity from geo-spatial fixity. While his remarks specify no destination for the Algerian boat, in the current geopolitical context, and much as the aforementioned placard indicated, the image of an entire country fleeing its borders carries connotations of an invasion seeking a destination

Yet Kamel's words are no call to mobilize. Rather, they express a fantasy of true mobility that refutes such constraining characterizations. Like the title of Teguia's film, Rome Rather than You, which replicates the chant of fans of a local soccer team, Kamel's statements historicize , recalling how the geographic space now designated as Algeria was for millennia a point of arrival, transit, and departure of peoples, religions, ideas, and goods, as well as a site of shifting historical roles, names, and battles and alliances.Similarly, the soccer fans'chant 'Rome rather than you' summons the ancient history of Berber resistance to the Roman Empire, underscoring how it, along with the centuries of conquests and colonizations since then, continue to shape life in the region. Exhorting the team to recreate a glorious era from the distant past, it derides as much as champions , implying that the team will necessarily fall short and consigni fans once again to internal, if not literal, exile. Ironically describing the very real exodus of young Algerians to Italy, the chant also reiterates fans' profound commitment to their team, and their eternal hopes that, through victory on the playing field, it will carve out an ever larger space for them in the atlas of champions..

Still, like the fans and the region, the chant cannot easily be pinned down. Its nuances shift, differentially mapping and mobilizing. It briefly encapsulates several salient moments in a turbulent history , in the course of which the region along the Northern Rim of Africa and its inhabitants have been identified as part of Barbary, Africa, Numidia, Rome, Christendom, the Islamic Empire, Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, Western Asia, the underdeveloped world, the third world, the Mediterranean, the Maghreb, and the Global South, and a myriad other cartographical sites. As with Kamel and Zina's conversation on the bridge, in which ancient and modern histories are simultaenously referenced in relation to contemporary trajectories , the chant emphasizes how older mappings have survived more recent ones, and that these older positionalities continue to inflect more recent affinities and aversions.

While tackling the region's mobility, Rome also revisits the mobilizing role of Algerian and African post-independence cinema. With its frequent nods to Algerian, anti-colonial, third, African, French new wave, and independent U.S. cinema and auteurs, Teguia's film at once pays tribute to longstanding cinematic conversations and opens up new ones.[5] Zina, whose worldview and positionality remain much more ambiguous than Kamel's, serves as the nexus for many of these, her character accentuating the meaning carried by women, and more particularly, unveiled Arab women, in the history of Algerian, third, and global cinema. At times shot, costumed, and speaking in ways that hint at a sharply analytic intellect and militant engagement, and in other scenes seemingly passive and bored, her character never appears entirely invested in the overt narrative that is Kamel's plan. From their first encounter, where he greets her as 'spoils of war', and she retorts by dubbing him a 'terrorist', Zina works within established parameters of the encounter, while seeming entirely aware and critical of them. When Kamel spins his vision of all Algeria crowding aboard the ship, Zina turns and scrutinizes the hillside city behind the camera, as if appraising both her own position and those of the unseen Algerians evoked by Kamel. Yet if her silence gestures at the historical role of women in cinema and their distinct positioning in formulations of nation and globalization, two moments in which her gaze unpredictably breaks the fourth wall hint that not only is she cognizant of the manner in which she is mapped, but that she directs her own relations in ways unexpected by Kamel and viewers alike. In the character of Zina, Teguia's film embodies on the level of character the webs of associations through which it frays a self-reflexive, unpredictable trajectory in images that often move much less than audiences would like, yet are impossible to pin down.

Itinerant Sightings

In sharp contrast to Teguia's extreme social realism, Nacer Khemir's Desert trilogy, Wanderers of the Desert (Al-Haʾimun) (1986), The Lost Neckring of the Dove (Tawq al-hamama al-mafqud) (1991), and Baba ʿAziz (2005) immediately propels audiences into universes of experience at once disorienting and deeply familiar. In the trilogy's first film, the schoolteacher Abdesslam, a product and promoter of models of knowledge that support state sponsored visions of progressive modernity, appears as initial protagonist, only to be swept away by another register of signs as the film unwinds. A proxy for viewers, Abdesslam from the outset confronts an utterly foreign realm of signification in the windswept, sand-buried Tunisian village to which he has been assigned. Having arrived prepared to teach the village children grammar, literature, and the history of their country, he is solicited instead by villagers that appear to have emerged directly from Persian miniatures to recover and transmit their city's mythical and neglected heritage. Intrigued by a village that the modern nation-state's employees deny exists yet which emerged from the sand dunes at his approach, whose young men forsake home to err endlessly in the desert, and where he is welcomed as the agent of a destiny in which he hardly believes, Abdesslam loses his bearings. He quickly abandons his promotion of modern education, becoming in turn a student of this new realm of signs. Midway through the film, he vanishes entirely.

Although witnessed by viewers, the circumstances of Abdesslam's disappearance resist logical exposition, least of all by the police inspector, that agent of modern order, sent to solve the mystery. This disappearance announces not just the film's definitive rupture with the realism favored by modernity, however, but also a broader break with the conventional processes of cinematic meaning-making through progressive exposition. In their place emerges a constellation of images and sounds that unsettle post-independence projects to align Tunisia and its cinema with a modernity presided over by Europe while sweeping away the markers by which location is usually established.

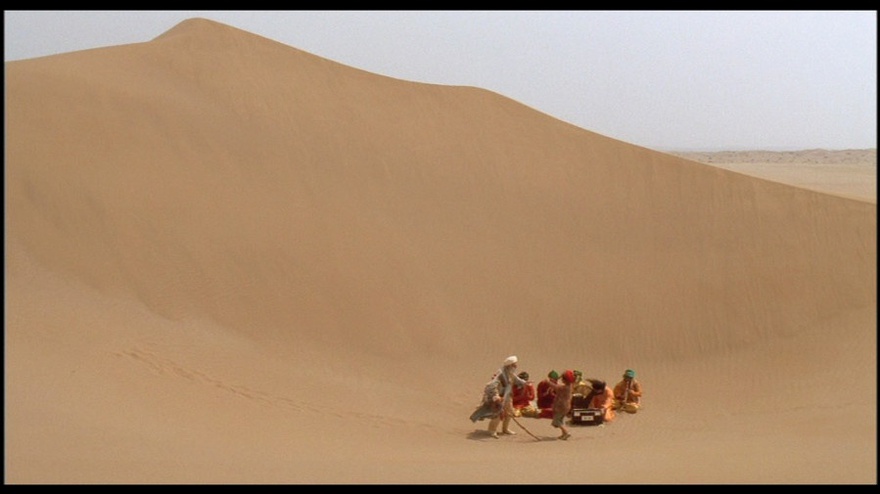

If Wanderers proposes a graduated unmooring from cinematic realism, the central and final films of Khemir's trilogy, The Lost Neckring of the Dove and Baba ʿAziz, immediately plunge audiences into a space-time continuum defying universe of signs, pitting affective and artistic maps against contemporary geopolitical ones. Seamlessly suturing together action across vast geographical and temporal distances, Lost Neckring remaps Spain and what is today southern Europe as part of a lost Islamic artistic and intellectual heritage: one that transforms the distance from North Africa to legendary cities such as Samarkand, to southern Europe, into a short journey on foot. If the film thereby rejects perceptions that today's national boundaries somehow represent discrete socio-cultural, ethnic, and religious identities, it also shuns the bellicose territorial claims of present-day religious extremists by presenting this logic defying universe as resolutely cinematic, recuperable only through art. Grounded, as are all three films, in a Sufism or mystical Islam that lures viewers to look simultaneously at surface meanings and beyond them, Lost Neckring of the Dove also places popular culture on a par with canonical works in a radical model of populist interconnection that encourages psychic and affective mobilities not bound by geopolitical maps past and present. The final film of the trilogy, Baba ʿAziz, again opens a cinematic universe inspired by literature, art, and dreams to more both plausible characters and narratives as well as their improbable, storybook counterparts. Linking multiple desert landscapes, characters from throughout countries often situated in the global South, and the language of the largely Shiʿa, theocratic Iran with those of the predominantly Sunni, avowedly secular, Tunisia, it follows the young girl Ishtar and her blind dervish grandfather, Baba ʿAziz, as they journey through the desert in search of an international meeting of dervishes that takes place every thirty years. As he tells her in Farsi, and as she in turn tells others in both Farsi and Arabic, there is no map or marked path; the meeting is accessible only to those capable of listening and seeing with their hearts. This absence of a mappable destination sums up the foundational principles of all Khemir's films, which generate mobility rather than simply recording motion. In contrast with films that animate a narrative, Khemir's trilogy never traces out fixed trajectories, nor do its films coalesce into definitive images. Instead, they lend themselves to multiple viewings that each time solicit new and always fluid, illocalizable connections.

Ambulatory Citations

While Khemir's films depart from Eurocentric worldviews on formal as well as thematic levels, thereby seeming to opt out of, or perhaps transcend, such formulations as national and world cinemas, Faouzi Bensaïdi's two most recent films, WWW: What a Wonderful World (2006) and Death for Sale (2011), explore what happens when popular film forms from Europe and America are reimagined from the perspectives of a Morocco geo-politically situated within the global South. Fundamentally a love story, or rather several criss-crossing, ill-fated, and absurdly romantic love stories, WWW places on collision courses characters struggling to maintain their bearings in a world where connection is everywhere promised but infrequently actualized. Traffic cop Kenza falls in love with a man she spies on a bus, not realizing he is hitman Kamel, with whom she speaks on the phone when he calls her friend, the occasional prostitute Souad. Kamel, in turn, has fallen for the woman who answers the phone, unaware that she is the police officer, Kenza, who trails him through the city. Meanwhile, handsome computer hacker and hard-working cargo van driver, Hisham, seeks with increasing desperation to move in real time through the borderless world proffered by the Internet, only to find himself blocked at every effort to cross national borders. Each character's search for connection proves ultimately fruitless, or rather, fatal, a fantasy initiated and maintained by circulating images and communications technologies that offer false leads, red herrings, and shattered illusions rather than enabling new relations. Throughout, WWW points more to other movies and media tropes than to social realities, its stylistic virtuosity raising questions about where Maghrebi film situates itself, as well as about how that positioning mobilizes and immobilizes its representations.

Centered on a Casablanca at once grittily real and pure film fantasy, WWW abruptly veers from its playful mash-up of genre and form to shatter the associations woven around that iconic city in cinematic imaginations, and through them, geographic ones. In his final appearance, would-be harraga Hisham stands on a small wooden fishing boat amidst a crowd of fellow clandestine immigrants staring open mouthed at a dazzlingly illuminated luxury liner. They begin to wave and call out as the first strains of Johann Strauss' Rosen aus dem Suden (Roses from the South) become audible, breaking into cheers and frantic waves as the volume of the music grows louder and the liner moves rapidly in a direct line towards them. One man calls out for the others to sit down, the boat rocking dangerously as he works to restart the motor. A static medium-long shot follows, the liner sliding along majestically to the upbeat, energetic notes of Strauss' waltz, its crushing of the men's boat audible only as a quick crunch below the surging music and hardly visible.

Although modelled on the luxury liner scene in Fellini's Amarcord (1973), in which the villagers of Borgo San Giuliano spend the night aboard their wooden fishing vessels to catch a glimpse of the celebrated SS Rex, the relations of the Arab and African men to the majestic ship are quite different from those of the Italian villagers to the symbol of the Italian Fascist regime. Rather than a source of national pride, this ship appears as an anonymous beacon of the North's economic superiority. Yet just as in Fellini's film, no one appears on deck to acknowledge those waiting in the water, not because the liner is engaged in a display of might, but because there are presumably no sights to see in the darkness far from Africa's shores. In this case, the absence of a returned gaze proves fatal rather than simply unsettling.[6] With Hisham's demise, WWW abruptly breaks off the line of development sketched out by the relationships with European, American, and other globally recognized cinemas it had previously developed. The film meets its absurd end just as Kenza and Kamel finally recognize each other, the couple gunned down by hired thugs as they stand between shantytown and brand new apartment buildings. They, and the film itself, expire amidst a clash of cinematic tropes and socio-economic realities, satisfying no established genre function. .

Bensaïdi's later and more consistently noir film Death For Sale proposesa more intimate and nuanced perspective of how the romantic requirements of that classic, now global, genre differentially intersect with the material and imaginative spaces of Morocco, and the global South more broadly. Blending film fantasy sequences with a social realism in which key information characteristically remains on the periphery of of shots and scenes, Death follows the more realistic protagonist, Malik, in his interactions with his friends Allal and Soufiane. Immobilized by unemployment and poverty in a city where the trafficking of drugs and counterfeit goods flourishes, the three young men bide their time with petty thievery, small schemes, and drinking and getting high. No sooner does Malik fall in love, than the trio drifts apart, Allal fleeing the city to elude police, and Soufiane joining the ranks of religious extremists after a failed purse snatching makes him a target of mob justice. Even before Malik devotes himself to his beloved, turning informant for the police in order to rescue her from prison, the film playfully tests the suitability of the socio-economically marginalized characters for classical cinematic romance. First catching sight of Dounia, his beloved, Malek approaches, and leaning against a white balustrade overlooking stunning mist shrouded mountains, offers her a sip of his Coca-Cola. As they glance, smile, and wordlessly flirt, streamers of film float upwards behind them, thrown, a downward pan reveals, by children joyfully pillaging a stash of VHS cassettes lobbed with other trash on an impromptu dump below.

Tightly framed against a backdrop of slow, romantic music, the two classically framed romantic lovers transform into props in an advertisement as the camera pulls back to frame them through a cafe window as movement resumes on the sidewalk in front of them. Remarkable not just for this abrupt and cynical shift in registers, sustained by Allal and Soufiane's leering disruption of the couple's reverie, but also for the way in which it trashes the film, before recuperating it as art, the scene fleetingly opens up breathtaking mobility and just as quickly shuts it down.

Yet, another kind of trajectory far less familiar to European and American film buffs manifests itself in a sequence in Death For Sale that begins when Soufiane walks away from a forest reunion with his buddies after agreeing to participate in their plan to rob a Christian jeweller. Standing on a rocky outcropping overlooking a clearing on the edge of the mountain forest, he seems to hallucinate, and perhaps performs, a scene clearly inspired by the religious DVDs he now sells on the street as recruitment tools. Rising from his seated position atop a boulder, he stares upwards, palms open, Sufi-esque chanting and drumbeats gradually growing more audible. From this view of Soufiane, shot in low angle, Death jumps to a long shot of a burning tree, the camera moving in as the young man emerges from behind it, naked and carrying a burning torch in each hand. Rapt by the flames, he throws the torches to the ground and approaches the tree, his outstretched arms mirroring its limbs while the camera encircles him. Mimicking the overwrought symbolism of a religious video while juxtaposing it with the kind of ecstatic trance scenario long associated with certain forms of Maghrebi music, the scene also plays with audience perspective as it vacillates between presenting the moment as a mental projection of Soufiane's and a diegetic event.[7] When Malik and Allal, returning to town along a dirt road, suddenly spot flames on the hillside, however, the scenario retrospectively takes on a disconcerting realism . Amidst these alternately converging and diverging cinematic modes emerge unexpected relations that are displaced before they can become definitive, continuing to act as a drag on the film's possible trajectories.

Such scenes as those discussed in this essay, and the films within which they figure, propose intersecting, conflicting, destabilizing significations, exposing the tortuous mapping of the Maghreb and the nations within it while insisting on renewed mobility for artistic and intellectual production from the region, as well as for its audiences. Slippery when it comes to categorization, yet pointed in their exposure of demarcations that immobilize, these films are no longer national, certainly not didactic, and yet far from celebratory of such easy categories as transnational and global. Rather, filmmakers like Teguia, Khemir, and Bensaïdi relentlessly probe how socio-economic and geo-political realities are brought into relation in and with entertainment.

Moving Shadows?

Thus, at the centre of each film discussed in this essay resides not certainty, but an elusive mobility. Malek, the surveyor protagonist of Tariq Teguia's Gabbla/Inland (2008) perhaps best sums it up in his diffident final lines. Sent to a semi-abandoned rural village that was once a theater of extremist violence in order to assess its suitability for connection to the electric grid, he encounters a migrant from an unknown country to the South and sets out with her for the Moroccan border in the desert. Just before they arrive at their destination, he is stung by a scorpion, and she drives him, half delirious, on an ATV to the border. As he is stumbling after her in the blazing sun at that line in the sand, he abruptly stops, and steps backwards. A moment later, he seems to hallucinate a conversation with his mentor Aziz in the desert twilight. To Aziz's question, 'How did you manage to get here?' Malek retorts with a mumbling half smile, 'Well anyway, I was only ever half here.'[8] Image and music speed up as the film cuts back to the woman walking along the border, just as she disappears into the blinding sun and desert, perhaps across the unseen border, perhaps not.

[1] This intentionally literal translation is my own.

[2] Kamel refers here to the root of the word Arab,ع ر ب, which as been historically defined as meaning 'to be on the move,' and 'to traverse'.

[3] This practice is not new, and has been used by asylum seekers for decades, but it certainly intensified after the Schengen Area standardized, and thereby tightened, the visa application process for member countries in 1995.

[4]When the hero of Franz Kafka's unfinished first novel, Amerika, sails into the New York harbor, he describes the Statue of Liberty as brandishing a sword. Franz Kafka, Amerika: the Man Who Disappeared. New York: New Directions Books, 2002.

[5] Filmic references include, among others and in addition to those already cited, Touki Bouki (Mambety 1973), Stranger than Paradise (Jarmusch, 1984), the films of the French nouvelle vague.

[6] In Fellini's film, the waves generated in the wake of the passage of the SS Rex apparently capsize the enthusiastic villagers' boats.

[7] The Sufi music and trance rituals thus referenced would quite likely be at odds with the strict, puritanical Islam of the group that Soufiane has joined.

[8] When the camera returns to the woman, another man, probably Aziz, is visible in the background with Malek.