Essays

Locating the Archive

The Search for 'Nurafkan'

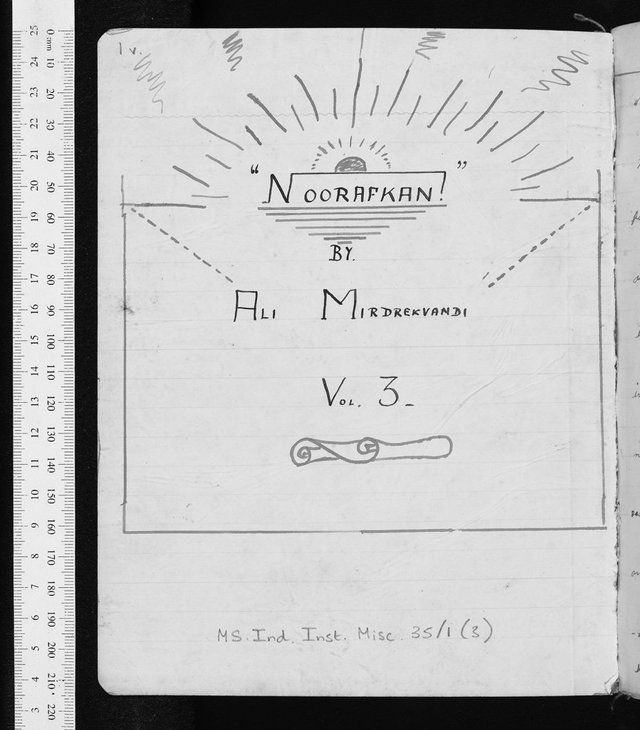

In 2009, by chance, I came upon an archive in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. It turned out that I was to be involved with this archive in different ways (reading and researching it, helping to raise funds to conserve it, writing inventories of it, and, ultimately, writing about it), over a period of approximately four years. The archive is named after the unpublished manuscript, Nurafkan, which lies at its heart. Nurafkan, or Irradiant in translation, was written by Ali Mirdrakvandi during the 1940s, while Iran was occupied by British and American forces. It is striking to say the least that Nurafkan – which runs to fifteen volumes and is perhaps 500,000 words long – should be written in English, for Ali came from a nomadic family from Lorestan. This choice of language has raised suspicions in both Britain and Iran: what events must have unfolded for a book like this to be written? And what role, in particular, might the British have had to play in it? While the story of the manuscript is certainly compelling, it should not eclipse the story itself – Nurafkan is an epic not only in length but also in content and narrative, and it is crowded with lavish characters (including, for instance, the memorably named Western Bawl). As Ali himself put it in a letter to his sometime English teacher, Major John Hemming:

I will not believe if millions of millions of peoples do say that my story is not a good book. Because I have read thousands and thousands of various books of Persian stories, of English stories, of Arabian stories, Turkish stories and American stories. No one of the stories was more interesting than my own story was.[1]

It is noteworthy too that John, who apparently only knew Ali briefly (during the 1940s), should try for nearly fifty years to ensure posthumous recognition of Ali's life and work, and that it should be he who bequeathed the original manuscript, which was in his possession at the time of his death, to the Bodleian Library in Oxford in 1996.

In 2003, Gholamreza Nematpour, a documentary filmmaker who lives in Khorramabad (Lorestan), 'ran into' a book called Famous People in Lorestan. 'I remember very clearly what it said,' he told me: 'An illiterate labourer wrote a book in English which was praised in Europe and the West'.[2] This brief and intriguing reference provided enough of an incentive for Gholamreza and his wife, Laleh Roozgard, to begin to investigate Ali's biography in anticipation of making a film. During the course of this research, Gholamreza and Laleh became increasingly committed to making Ali's stories – his life stories, as well as the stories he had written – as widely available as possible. These stories are twisted into the histories of Reza Shah's brutal policies of nomadic 'sedentarization' and 'resettlement', of the Trans-Iranian Railway, and of hunger and devastation during the Second World War. They speak of rural poverty, of lawyerly corruption, of inequality and addiction. However, Gholamreza and Laleh's first task, as it turned out, would be to prove that Ali existed at all, and then, secondly, to prove that it was he (and not the British) who authored Nurafkan.[3]

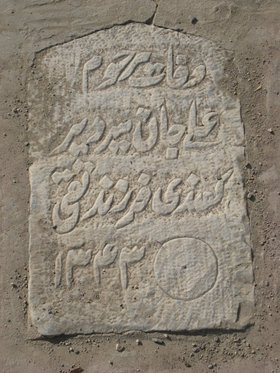

In 2012, Gholamreza, Laleh and I met in Borujerd, where Ali is buried. The following year, Gholamreza finished his film, No Heaven for Gunga Din,[4] and I finished a book, Yeki Nabud (One There Wasn't), which is inspired by the Nurafkan archive.[5] The title, Yeki Nabud, reflects my preoccupation with 'wheres' and 'nowheres', absences and presences, visibility and invisibility. Although these preoccupations are borne of my encounters with the stories that are told (and not told) in the Nurafkan archive, it strikes me now that they are also relevant to my experience of the archive, particularly since I met Gholamreza and Laleh. It is – in part – through my relationship with Gholamreza and Laleh that I have been prompted to ask after the location of the archive (where is it?) and in what way it acquires visibility (how is its 'seeability' achieved, and under what conditions?).[6] It seems to me that the different ways these questions are answered will potentially transform the kind of object the archive is understood to be.

In one sense, the answer to these questions is obvious. The Nurafkan archive has a physical presence, as one intuitively (and perhaps somewhat conventionally) imagines that most historical archives have. Indeed, it is precisely the physicality of documents and objects, the smell and feel of the 'originals', the sheer here-ness of what-once-happened – of holding 'the past' in one's hands – that explains in part the fever that grips so many people who work with archival materials. By 'archive fever' I mean both the 'homesickness' that Jacques Derrida describes, the 'nostalgic desire for the archive, an irrepressible desire to return to the origin,'[7] as well as the physical sickness, which, as the historian Carolyn Steedman more prosaically points out, is caused by:

…the dust of the workers who made the papers and parchments; the dust of the animals who provided the skins for their leather bindings. [...] [By] all the filthy trades that have, by circuitous routes, deposited their end products in the archives.[8]

Gholamreza and Laleh can experience the first of these fevers (and, as it happened, they did), but not the second. For, '[a]s you know', Gholamreza wrote, 'making a trip to England to gather information and to see Ali's manuscript is impossible for me.'

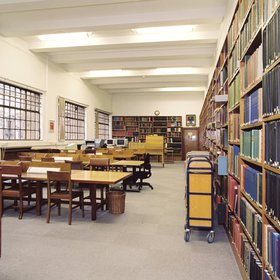

A physical presence implies, by definition, a physical location. This physicality – the physicality of the archive – is one of the key themes of Alain Resnais' short film Toute la Mémoire du Monde (1956),[9] in which he draws attention to the archive as a formidable, indubitable, even a foreboding, presence. Airborne shots of the dome of the Bibliothèque Nationale – France's national library and site of a substantive part of France's national documentary heritage – show the archive to be 'a fortress in the midst of both the city and the envisioned sea of history.'[10] Resnais' camera finds 'locked doors, books behind bars and shelving staff that look like guards.'[11] Toute la Mémoire du Monde conveys, in short, as the multimedia artist Uriel Orlow describes it, a 'visual vocabulary of the archive as prison.'[12] And certainly, just as 'words are imprisoned in the Bibliothèque Nationale,'[13] so they are imprisoned in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. It is the physical location of the Nurafkan archive that renders it inaccessible and invisible, for all intents and purposes, to Gholamreza and Laleh.

The Nurafkan archive is 'arrested'[14] by more than the boundaries or borders that mark the edge of its physical territory (the boundaries of the library building, of the Special Collections' temporary Reading Rooms, of the acid-free boxes in which the documents are stored and protected). Although the arched silence and muted light of the Bodleian interior encourages its readers to think of the library as a 'smooth' and uninterrupted environment, in fact this space is puckered and roughened by many different kinds of barriers. To take just one example: the Bodleian Library requires payment for scanned materials (for its costs, for permissions, and for copyright where this is relevant). However, the current deathly embargo on Iran means that Gholamreza and Laleh do not have access to international credit cards, and are not, therefore, in a position to pay for the reproduction of archival – or indeed any other –[15] documents. This is especially frustrating for them, since the archival documents are indispensible to 'proving' the contested authorship of Nurafkan. Thus it was that I became, for a while, something of an archival 'mule' – crossing and re-crossing the borders between the Bodleian Library in Oxford and Gholamreza and Laleh in Lorestan. The physical component of this task (visiting Oxford and marking up documents for the library to copy) was just one small part of it. I also crossed linguistic borders (translating some of the Bodleian's more esoterically worded policies into a more recognizable English), economic borders (I used my credit cards to pay for scanned documents), and political borders (I used my email address to receive the images).[16]

These procedures – visiting, selecting, requesting, paying, and receiving – are routine, even banal. Yet they are the means through which the Nurafkan archive is made visible to me, but not to Gholamreza and Laleh. The space of the Bodleian Library in Oxford is heterogeneous and complex: it is creased on the 'inside' by borders that appear, at least initially, to be on the 'outside'. Paying attention to these borders, accounting for and reacting to them, engaging in the 'multifarious battles and negotiations' that they compel, is part of what Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Neilson describe as 'border as method.'[17] The border, for them, is a way of doing research. For us, the research process itself was bordered, and much of our energy was dedicated to managing the practices of 'border reinforcing' that shaped how we, as researchers, were differentially included (me) or excluded (Gholamreza and Laleh) from access to archival resources.[18]

Although the spatial location of the archive defines, in some way, the scope of the archive's visibility, it does not entirely determine it. The commitment and achievements of Gholamreza and Laleh have ensured that at least some part of the manuscript is 'in' Iran. As it turns out, this has not in itself resolved the problem of the archive's 'seeability'. On the contrary, Gholamreza tells me that the archival images can only be 'introduced cautiously'. The very fact that the scanned pages of the manuscript, written by a 'famous person of Lorestan' (as the title of the book that Gholamreza chanced upon described the author of Nurafkan), cannot be enjoyed locally suggests that the visibility/invisibility of Nurafkan cannot be accounted for solely with reference to its physical presence in Britain, or by its absence in Iran. It is for this reason that I am prompted to turn to the relations between these two nations in order to look for an alternative explanation.

*

One version of the genesis of Nurafkan, and of the relations between Ali Mirdrakvandi (who wrote the story in Iran in the 1940s) and John Hemming (who bequeathed the story to the Bodleian Library in the 1990s) goes like this:[19] John and Ali met while John was serving as a Pioneer Labour Control Officer for the British forces in occupied Iran during the Second World War. Ali applied to John for work, and at the same time asked John to help him to improve his English. John encouraged Ali to write stories, and so began Nurafkan. While working in the American officers' mess in Tehran, Ali also wrote a short fable called No Heaven for Gunga Din: Consisting of the British and American Officers' Book. Although John managed to get No Heaven published by Victor Gollancz in 1965,[20] he had no similar success with Nurafkan.

In one of his accounts of Nurafkan, the late Robert Zaehner, Professor of Eastern Religions and Ethics at Oxford University, explains that it was quite common, following the withdrawal of the British and American armies from Iran at the end of the Second World War, for remaining British and American personnel to take on staff who had been left without work. Zaehner himself was in Iran at that time, 'and although I did not really have any employment to offer, so remarkable was he [Ali] that I took him on as an extra houseboy.'[21] Zaehner claims that Ali sometimes spoke of a story that he was writing during this period of employment and, on occasion, consulted Zaehner about it. It was on the basis of these discussions that Zaehner surmised that the story was folkloric, and perhaps of Zoroastrian origins. After six weeks Ali Midrakvandi 'disappeared, taking the unfinished manuscript with him,'[22] and Zaehner did not hear of either him or the story again until he was contacted, in his capacity as a scholar of Eastern Religions, by John Hemming in 1963. On reading both the manuscripts, Zaehner appears to have used his contacts to help John to find a publisher for No Heaven, and to have written several academic papers on Nurafkan, which he believed paralleled and illuminated the Zoroastrian cosmogony of Bundahishn.[23] During his next trip to Iran, Zaehner delivered two lectures on Nurafkan to the British Institute of Persian Studies in Tehran, and at the same time initiated a search for Ali. Although this search gave rise to some considerable press coverage, Ali was not to be found.

The story of Ali, and of his relations with the British, continues to resonate in the present. For example, when I ask Gholamreza and Laleh how Ali is remembered in Borujerd (Lorestan), they tell me that their plans for an annual award for young writers – which they had intended would be given in Ali's name – cannot go ahead on account of the government's suspicions that the 'real' author of No Heaven for Gunga Din was either John Hemming or Robert Zaehner. Suspicions like these appear to have endured since at least the 1970s, when Professor A. D. H. Bivar, another British academic with an interest both in Ali Mirdrakvandi and in Robert Zaehner, picked up the story. 'I often heard the opinion expressed [by Persian literary scholars]', Bivar wrote, 'that no such person as Midrakvandi ever existed, and that writings allegedly his were the compositions of Zaehner or Hemming, concocted by British officials for propaganda reasons! Several readers in the UK, impressed by a well-known hoax in Persian studies, even speculated that the story of Mirdrakvandi was similarly an elaborate hoax.'[24]

The enduring potency of these stories suggests that, while the 'unseeability' of the Nurafkan archive in Lorestan is most obviously due to its physical location in Oxford, it is more fundamentally explained by its 'location' in the relations of suspicion and rumour that so often connect Iran and Britain. While this suggestion displaces – perhaps problematically – the significance of the archive in space, it foregrounds its location in time. For it is in time, or rather with time, that the power of rumour lies. Rumour, Veena Das argues, has the power 'to actualize certain regions of the past and create a sense of continuity between events that might otherwise seem unconnected.'[25] It does this by animating what Das calls 'unfinished stories', and by bringing them to life in the present. Importantly – and this is as true of the relations between Iran and Britain as it is of the relations between Sikhs and Hindus that Das discusses – rumour does not 'make ... grievous events out of nothing.'[26] It is not language that creates scenes of devastating violence. Rumours, instead, are enmeshed in histories of conflict.[27]

In Iran, such histories of conflict are often tied up with foreign powers. Indeed the view that alien influences, nofouz-e biganeh, or foreign dangers, khatar-e kharajeh, or foreign hands, ummal-e kharajeh, are lurking behind the curtain, posht-e pardeh, or behind the scenes, posht-e sahneh, is a common one.[28] And why should it be otherwise, given the country's long experience of imperial interference by Russia, Britain, and the USA? In all this long experience, it is perhaps the 1953 coup against Mohammad Mossadegh, following Mossadegh's attempts to nationalize Iranian oil, which stands out as the most abominable of the foreign powers' offences. No matter how distant in chronological time, the events of 1953 remain painfully alive in the present. It was to that unfinished story, for instance, that a relatively unknown mollah, Ali Khamenei, referred on the 14th anniversary of Mohammad Mossadegh's death in 1981, just two years after the Iranian Revolution. Khamenei – today the Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran – furnished the story a triumphant ending, which also doubled up as a warning: 'We are not liberals like Allende and Musaddiq,' he exhorted, 'to be snuffed out by the CIA.'[29]

Earlier, I used the concept of 'border as method' to draw attention to the sinuous complexity of space, and to the processes by which space is differentially 'filtered'. The concept of rumour can be similarly exploited to illuminate the complexity of time – not of time laid-out, smooth, and straight in a line, but rather, of time as rucked-up and creasing. 'In the folding and refolding dough of history', Steven Connor writes, 'what matters is not the spreading out of points in time along a temporal continuum, but the contractions and attenuations that [...] bring distant points in proximity with each other.'[30] Connor is describing Michel Serres' topological conception of history in which time is likened to 'a crumpled handkerchief, in which apparently widely separated points may be drawn together into adjacency.'[31] This, as I have noted, is how rumour operates – not by establishing relations of cause and effect, but by mobilizing chains of connections.[32] Rumour, one might argue, is one of the techniques by which time is folded in upon itself, by which it is gathered and re-gathered and released – often with violent consequences. When rumour sets to work, atrocities of the past often end up lending 'veracity' to what is heard and said in the present.

Gholamreza, Laleh and I, among others, consider Ali Mirdrakvandi to be the author of Nurafkan and No Heaven. Yet the images of Ali's manuscript, as I have already noted, are often prohibited because, Gholamreza tells me, while the Iranian authorities believe that Ali existed, they are also convinced 'that they [the British and Americans] used him for their own special purposes'. Ali could have been a spy, without his even being aware of it. Such routine distrust has repercussions. It can make it hard to build relationships – in politics, in friendship. It justifies censorship. It can have tragic consequences: 'One does not compromise and negotiate with spies and traitors', Ervand Abrahamian writes: 'one locks them up or else shoots them.'[33] Abrahamian's broader point is that, while the coup against Mossadegh had many severe implications for Iran's relations with America and Britain, it also had implications within Iran. It contributed, for example, to what Abrahamian, following Richard Hofstadter, calls 'the paranoid style in Iranian politics',[34] a style which includes 'the conviction that only force could forestall repetition of 1953.'[35]

In the end, is it surprising that it is easier to imagine a world in which the constraints that prevent Gholamreza and Laleh from visiting the archive in Oxford are lifted, than it is to imagine that the relations between Iran and Britain could be different? '[S]tructures of feeling', as Ann Stoler puts it, are nearly always joined to, if not inseparable from, 'fields of force [...] of a longer durée.'[36] Doubt, mistrust, and suspicion are 'politicized cognitions', shaped by experiences of acts of hostility and aggression. Who, after all, was Robert Zaehner? A giggly, gin-drinking Oxford Professor. But Robin Zaehner (as he was also more commonly called) was a central figure in the British strategy to overthrow the democratically elected Prime Minister, Mohammad Mossadegh. As a press attaché in Tehran during the mid-1940s, which was the period of Ali's employment, Zaehner successfully cultivated an extensive set of networks that cut across the court, the bazaar, the press, and the majles (the Iranian parliament). Robin Zaehner knew all the important people, and other people too. Which is why, in the early 1950s, he was despatched back to Iran by MI6 to exploit his connections and to help to execute a planned coup d'état. Rumour was chief among his venal resources.

Where is the archive? I have located the Nurafkan archive multiply, and understood it to be differently constituted in each case: as a physical object, as border activity, as sets of relations that stretch and squeeze different times and spaces, histories and nations. Yet, it is with regard to the archive's 'location' in the temporality of rumour, suspicion and paranoia that I feel the most despair. For if it is here that the Nurafkan archive is most firmly situated, then its 'visibility' seemingly impossibly requires that time itself be unstitched and refolded.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My deepest thanks to Haedeh Izadi, who helped make possible so much of the work that I describe in this article. Thanks also to Masserat Amir-Ebrahimi, and especially to Gholamreza Nematpour and Laleh Roozgard for their help and support. All the views expressed here, and any errors, are entirely my own. My thanks to Gillian Grant (Oriental archivist) and Nick Cistone (photographer) at the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, for their enormous generosity with their time and images.

[1] Undated letter from Ali Mirdrakvandi to John Hemming, probably written between 1947 and 1949. Document owned by Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, MS Ind. Inst. Misc. 42.

[2] This and all subsequent references to Gholamreza Nematpour's account of Nurafkan are cited, with his permission, from our personal correspondence.

[3] Gholamreza Nematpour and Laleh Roozgard can be contacted on pezhman1355@gmail.com

[4] No Heaven for Gunga Din (Baraye Gunga Din Behesht Neest), DVD, Lorestan's H.O.C.I.G, Iran, 2012.

[5] I take this title from the second half of the phrase yeki bud, yeki nabud. In direct translation, this Iranian equivalent of 'once upon a time' means 'one there was, one there wasn't'. These words, with which so many Iranian stories begin, seem to me to warn of the instability of stories and their contents. They are an invitation to ask: to what does a story refer? Of what and when does it tell? In what different kinds of ways is it possible to believe in a story, or not believe, and with what consequences?

[6] I am following Gilles Deleuze here, who argues that '[v]isibilities are not to be confused with elements that are visible or more generally perceptible, such as qualities, things, objects, compounds of objects...' Gilles Deleuze, Foucault (London: Continuum, 1999), 45. Instead, visibilities are 'first and foremost forms of light that distribute light and dark, opaque and transparent, seen and non-seen, etc.' (Ibid., 49). Visibilities organize, in other words, what it is possible to see or not see, including the subject, 'who is himself [sic] a place within visibility' (ibid., 49). See Bal for a discussion of the practical, methodological and disciplinary/interdisciplinary implications of this conception of visibility, in which the organization of seeing precedes the visuality of the object. Mieke Bal, 'Visual essentialism and the object of visual culture,' Journal of Visual Culture 2.1 (April 2003): 5-32.

[7] Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. E. Prenowitz (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998), 91.

[8] Carolyn Steedman, Dust (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001), 27.

[9] Toute la Mémoire du Monde, 35 mm, Films de la Pleiade, France, 1956.

[10] Uriel Orlow, 'Latent Archives, Roving Lens,' Ghosting: The Role of the Archive within Contemporary Artists' Film and Video, eds. J. Connarty and J. Lanyon (Bristol: Picture This Moving Image, 2006), 37.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Derrida, op. cit., 2.

[15] This also served to restrict their access to other archives, including especially newspaper archives.

[16] All of which suggests that the 'solution' to cracking open borders is not always or solely digital.

[17] Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Neilson, 'Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labor,' transversal (March 2008) http://eipcp.net/transversal/0608/mezzadraneilson/en.

[18] It is worth noting that staff at the Bodleian Library were themselves uncomfortable with these distinctions, and that I was often thanked for acting as Gholamreza's proxy.

[19] This version is largely drawn from A. D. H. Bivar, 'Reassessing Mirdrakvandi: Mithraic echoes in the 20th Century' Proceedings of the Third European Conference of Iranian Studies (Wiesbaden: Dr Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 1998).

[20] Ali Mirkdrakvandi, No Heaven for Gunga Din: Consisting of the British and American Officers' Book (London: Gollancz, 1965).

[21] Robert C. Zaehner, 'Zoroastrian survivals in Iranian folklore,' Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies 3 (1965): 88.

[22] Ibid., 89.

[23] Zaehner's interest in Nurafkan – which Hemming (rightly in my view) exploited – probably goes some way to explain how the manuscript came to be considered for inclusion in the Bodleian archives at all.

[24] Bivar, op. cit., 61.

[25] Veena Das, Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 108.

[26] Ibid., 209.

[27] Ibid., 209.

[28] Ervand Abrahamian, Khomeinism: Essays on the Islamic Republic of Iran (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 111.

[29] Ervand Abrahamian, 'The 1953 Coup in Iran,' Science and Society 65.2 (2001), 214.

[30] Steven Connor, 'Topologies: Michel Serres and the Shapes of Thought,' Cultural Theory: Economy, Technology and Knowledge, Volume 4, ed. D. Oswell (London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2010), 404.

[31] Ibid., 402.

[32] Das, op. cit., 108.

[33] Abrahamian, 1993, op. cit., 131.

[34] Abrahamian is careful to distinguish between a paranoid style and mode of expression in Iranian politics, and a national clinical psychological disorder.

[35] Abrahamian, 2001, op. cit., 213.

[36] Ann L. Stoler, Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), 252.