Interviews

The Woven Archive

Héla Ammar in conversation with Wafa Gabsi

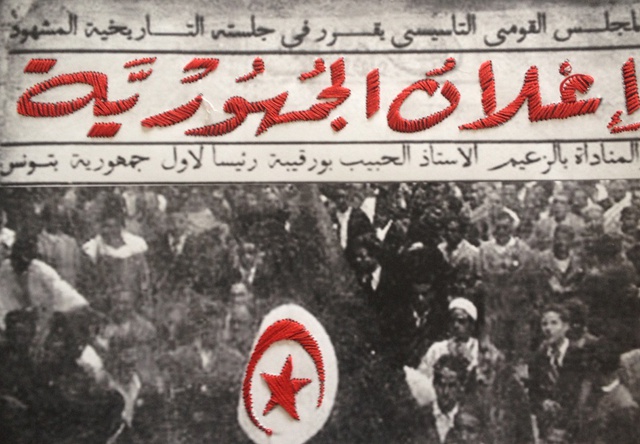

Héla Ammar is a visual artist, PhD graduate of law and a self-defined militant feminist. In her photography, she has often chosen to put herself centre stage in order to express her opinion on topics that shape the contours of an endlessly shifting, contemporary feminine identity. Tarz (Embroidery) (2014), constitutes the artist's latest body of work, which was first presented at Le Violon Bleu in Sidi Bou Said, Tunisia. Tarz explores the current Tunisian political situation as a historical memory where recollections of a fierce, popular-led resistance collide. In order to construct this site of memory, Amar combines archival objects and photographs, blending embroidery with sensitive official archives, provoking a back and forth between memory and feeling. The result is a temporal space where past and present become intermeshed. Through this, the artist attempts to understand the image of the Tunisian revolution through the imprint it has left on the sphere of her memory.

Wafa Gabsi: In the context of your new work, Tarz (Embroidery), why and how have you used embroidery, a technique you have never experimented with before?

Héla Ammar: As you know, Tunisia is in the middle of a transitional process. Throughout the drafting of the constitution, arguments have raged between the elected representatives of the different parties, each one trying to assert their idea of the common good. In the midst of all these discussions, a remark from one of the deputies attracted my attention. Responding to an accusation that had been thrown at him, he replied with this metaphor: 'You are sewing, while over here we are doing embroidery!'

It's most likely this remark which inspired me to make these installations. Above all, embroidery brings to mind time, patience – self-sacrifice, even, and precision. It is laborious work and tiresome in the long run. The result is often as valuable as it is delicate. The materials involved are high-quality and fragile and to use them requires a lot of dexterity and care. It was because of this that the technique occurred to me as the most appropriate medium for talking about the long political process Tunisia has used to reach democracy. The link with the archives quickly followed, as the archival process echoes as much the construction of the modern state as it does my personal history.

WG: Approaching this work, what importance did you give to each element?

HA: Each element has a particular symbolism which echoes our experience and the current political situation. The approach may seem poetic, but it also deals with an often frightening reality. The words embroidered in Arabic script on white linen are the founding values of the republic, values which men and women sacrificed themselves for, which were then often flouted and which the Tunisian people have brought back at the cost of their lives. Each part is associated with an object that symbolizes the repression we have experienced. The contrast is therefore more pronounced. Without wanting to give away the whole work (which will be on show in May at Violon Bleu in Tunis), I'll say that these installations are a part of a wider collection where photographs and archival documents merge. So these elements oscillate endlessly between a heated current state of affairs and a past that defies time.

WG: During our interview about this new work, Tarz, you showed me a series of photographs, one of which intrigued me: it was the photograph where the writing has been unpicked. What is it that interests you in this act of making and unmaking embroidery? Is it to trigger a reaction from the senses, the body, and memory?

HA: The history of Tunisia since independence comes from a long process of construction and destruction. The Tunisian state was constructed over time, but, equally, it was over time that its founding principles – even the idea of citizenship – were eroded in Tunisia. The big political decisions that were made created the glory of Tunisia and elevated it to the rank of an example among Arab countries – the modernization of state institutions, equal access to education and to knowledge, together with the women's statute, are some examples among others. In the same way, other decisions served only to tarnish its image; inequality and social injustice, the erosion of basic freedoms, to mention but a few. It is what we have experienced these last few years in particular, and it's precisely in reference to this experience, that the act of making and unmaking embroidery (in loops) takes on all its meaning in this work.

Here I call on both memory and the body: the act of unmaking or deconstructing what was made or built at the cost of huge efforts and heavy sacrifices are never as trivial as the reconstruction of what was unmade. While we're on the subject, I want to tell you a little anecdote that will illustrate this point perfectly. Once all the parts were finished, I asked the embroiderer to undo everything she had embroidered. I remember that she got somewhat angry at my request, and pointed out to me that she had devoted many hours and put all her heart into it. As the only explanation for my request, I asked her what she felt when I told her to undo her work. She replied: 'It broke my heart.' This is exactly what one feels when one sees the values that entire generations sacrificed themselves for being trodden underfoot, destroyed; undone. It takes willpower, belief and courage to build it all afresh. This is exactly what our entire society is in the process of doing.

WG: How do you call on memory? And why? Does revisiting the stories of the past today imply the possibility of finding in those stories a new approach in your work?

HA: This work effectively calls on memory, but it is not, for all that, an act of commemoration. Indeed, the work is neither a reconstruction of the past, nor is it a commemorative reminder. My approach is not descriptive; on the contrary, it is allusive. The past is not recreated in my work, rather, sometimes it is invoked and other times alluded to. Incidentally, turning to the archives fits perfectly into this approach. The documents and other archival objects are not simply reproduced exactly as they were. I manipulated and sometimes distorted them in such a way that their evocative force goes beyond mere factual description. As a result, if memory occupies an important place in this work, it also leaves a central place for imagination, and even to the feeling of the collective unconscious. It is this very approach that I have always privileged in all my work. I don't do reporting; my approach is conceptual and calls on all the senses. It doesn't offer responses; rather it encourages questioning and reflection.

WG: What is important about the past, to which you make reference with old, found documents? Why this resurgence regarding the archive?

HA: I grew up with this sense of belonging to an independent state heading towards modernity. Values like freedom, dignity, equality and justice were passed on to me through the memory of my grandfather, a nationalist resistance fighter and kingpin of the liberation of Tunisia from the grip of colonialism. I carried them with me through the story of my family, without ever really worrying about where they came from exactly. They nurtured my childhood and helped to construct my identity as an adult. Strong with this immaterial heritage, I was never really concerned with family archives, no more than I was with national archives. I knew that they were there, doubtless within reach.

It was the events that, since 14 January 2011, still shake my country, which pushed me to go back there. The revolution came as a reminder of the values which Tunisians fought for – recalling but also reaffirming them, as if they were worn away over time. Other events occurred to throw into question once again the very founding principles of the republic, our way of life; our national identity. These are the immense upheavals which made me go back to the archives.

As for what interests me: the archives as tangible traces of the past, or as a receptacle of memory, also constitute a safe investment; it is precisely when the future appears uncertain that one returns to the past. One thus interrogates memory, be it collective or individual, to find answers, not only about the past but also about the present and the future.

WG: How have you used this archive in the context of your new work?

HA: In all likelihood, I was looking to be reassured of my convictions: that we had built something strong and long-lasting, and that the threats that weigh on the future of Tunisia will not be able to defy its history. But beyond these expectations, and above all the anxieties which they echo, there is an analysis to make: if it is such that the archive in itself is a place of memory, the scattering of the archive leads to the de facto fragmentation of memory.

Initially, the family archives were gathered together in the large, main family house, in which I spent a good deal of my childhood anyway. The children, male and female cousins, grew up and went to live elsewhere, taking with them their part of the archive. Another part stayed in the house and was destroyed through lack of maintenance, and yet another part was taken by researchers and historians and then lost. So it was up to me to put the pieces back together. The same assessment is true of the national archives. From 1999 they were centralized in a modern building, in accordance with the norms of indexing and of conservation of archival documents. They are essentially made up of the archives of public institutions (administrative and ministerial) which had a legal obligation to deliver their archives to the National Archives. Other archives are made up of private donations. All together it gives an impression of coherence and richness, putting aside the fact that there are no photographic or audio-visual archives. To my great regret, I learned that the National Archives didn't have the means to acquire them (because above all it's about private collections put on sale), nor to ensure their conservation. The National Library houses this genre of documents. Unfortunately, the conditions for accessing the National Library, as well as the regulations regarding consulting the archives, are particularly strict.

WG: How do you make the link between your sensitive archive[1] and the archive of national history?

HA: Effectively, in my approach family archives, my own memories, and the national archives that I chose to consult, are all interwoven. I combine the intimate with the public, the individual with the national, because they are, in my case, two sides of the same coin. I cannot separate the memories of my grandfather from the history of the country, in the same way that I cannot cut myself off from the environment in which I developed. In this most recent work, for example, this translates into a deliberate mix between national documents from the period and photographs drawn from family archives.

Sometimes I place objects belonging to my grandfather, which bring to mind his affiliation to a founding era and to the national movement, in modern places. This mix – this superimposition, even, is for me the only way to see the 'whole picture'. I'm not looking to substitute the work of a historian, or to elevate feeling above knowledge, but rather to give a more intimate perspective on the founding era of contemporary Tunisia.

Unfortunately, this dimension is almost completely absent from any approach based on the archives. So the archives serve historians or researchers alone, and the way in which they are used serves an exclusively academic knowledge. The archives thus have a particularly specialist audience that is selective and therefore limited. In my opinion, the appropriation of archives by artists will happen in a way that gives the archives greater visibility, as well as showing them in a new light, where (academic) knowledge and feeling are not separated.

WG: What importance does the current political situation have on your work?

HA: I have always drawn upon my experience, in the same way that I have always drawn inspiration from my everyday life in order to express myself. Furthermore, I have always considered the artistic act a political act, insofar as the artist takes on their own vision of the society in which they developed. Moreover, it is for this reason that a large part of my photography deals with the position of women in Tunisia. The revolution gave me the opportunity to deepen this approach by taking on more delicate subjects, such as repression under the old regime. In 2011 I had the opportunity to visit Tunisian prisons, which allowed me to witness the state of the penitentiary system in Tunisia and more generally the violations of the rights of prisoners.

Today, the current political situation weighs more and more heavily on my everyday life. I do not, however, believe to be the only one in this position; the events which we have lived through since the first uprisings have invaded the privacy of all Tunisians. This situation, beyond its strictly political and therefore a priori public nature, continues to provoke questioning and challenging on a personal level. Each one of us looks for points of reference, and my new work likely falls into this category.

WG: Do you forge links with Derrida's famous expression 'mal d'archive' ('archive fever')? How do you explain your interpretation of it?

HA: Using psychoanalysis, Freud thought that in reviving the original memory he could heal his patients. But it seems that the archive is nothing but a reconstruction, a restoration brought about afterwards. The memory itself, as it was on the date it was made, is therefore sealed off; lost forever. This is what Derrida called archive fever.

I don't think that there is a direct link between my work and this thesis, inasmuch as I do not position myself on a plane of trauma. It remains that there is a particularly troubling relationship to the archive when it comes to confronting your own feelings. I realized during my research that official documents, even if they are a mine of knowledge, remain cold and impersonal. In this sense, they can be frustrating or deceptive with regards to the expectations which one attaches to them. The emotional burden is even stronger because it is amplified by time. The archive is thus fantasized, and because it is excessively the bearer of hopes, it is often short of feeling. No concrete memory could totally match it; at most it would be a pale reproduction.

In its literal sense, Derrida's famous expression could equally describe a recognizable reality: we are literally in need of archives,[2] in that they are often impossible to find, or in any case, inaccessible. The most obvious example is that of artistic archives. The state acquired thousands of works of art and has succeeded in creating a priceless collection. This collection has unfortunately never been valued. To this day, there is not a single museum of modern or contemporary art in Tunisia. Worse still, the works which were acquired are poorly looked after, piled up in dusty, humid storerooms. They are put in jeopardy, and they are always inaccessible to the public. As a result, Tunisians are deprived of their own artistic heritage and therefore a large part of their cultural memory.[3]

WG: In your opinion, what archives does art history in Tunisia need?

HA: Today, Tunisia needs points of reference. Tunisians need to know their real history, propaganda aside, with all that that history holds, the positive but also the negative. For us it is about exercising a real right to knowledge. This right to the truth is essential for us to reclaim our past, and to reconcile ourselves with the worst moments of our history. These two conditions alone will allow us to go forward.

In this exact moment in our history Tunisia needs its political archives, especially those who have, for a long time, been confiscated by the government of the day. Moreover, it is what a large part of civil society are demanding; they are campaigning for the opening of the secret police archives in order to bring to light the dark years of the dictatorship.

Furthermore, considering the level of importance that is put on culture in the history of peoples, one can imagine Tunisia's need for its artistic archives. These archives should first of all be accessible to the public, with a view to an improved understanding of their cultural heritage. But above all they are necessary for the writing and unification of Tunisian art history. On this note, what we can say is that our art history is – if not totally incomplete – then at the very least fragmented. Effectively, we can establish that little of what has been written allows for a reading of Tunisian artistic production that is both comprehensive and analytical.

Tarz will be on show at the Violon Bleu in Tunis from 12 April 2014–12 May 2014.

Héla Ammar is directly inspired of her daily experiences, her life, of the way she communicates to bring her vision on subjects such as the image and the feminine identity in Arabic Mediterranean cultures. Since 2003, her work has been regularly showcased in Tunisia and abroad. She took part in numerous solo and group shows in Tunisia and abroad (Germany, France and Spain). Her work has been shown in various international art fairs including World Nomads New York 2013, Dream City in 2010 and 2012, Les rencontres photographiques de Bamako 2012, Marrakech Art Fair 2010, ArtDubai 2008, ARTMAR2007, Biennale de Barcelone, Spain 2007, ArtParis-AbuDhabi 2007.

[1] 'This concept is touched upon in the work of Michel Foucault, L'Archéologie du savoir (1969), Jacques Rancière, Le Partage du sensible (2000), Les Noms de L'Histoire (1992), Reinhard Koselleck, L'Expérience de l'Histoire (1997), Arlette Farge, Le Goût de l'Archive (1989) and Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain (2010).' Julie Abbou, 'L'Archive Sensible', Calenda website, 11 December 2013 http://calenda.org/268790.

[2] mal d'archives literally means 'in need of archives', although it can also mean 'archive sickness' or, as it is commonly translated, 'archive fever'.

[3]See my response to Ibraaz Platform 006: http://www.ibraaz.org/platforms/6/responses/143/.