Interviews

Writing by Example

Meriç Algün Ringborg in conversation with Nora Razian

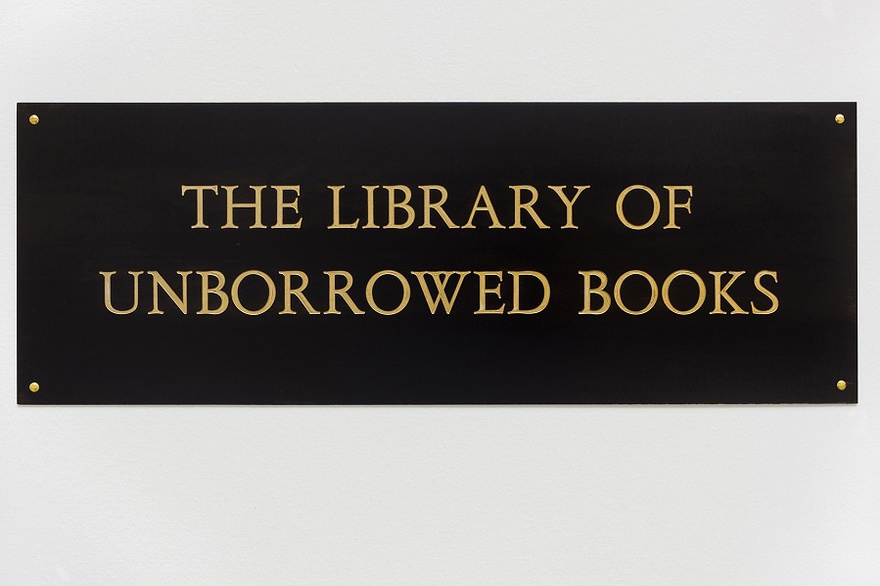

In this interview, Meriç Algün Ringborg talks to Nora Razian about her most recent work A World of Blind Chance (2014) and her ongoing work The Library of Unborrowed Books (2012) most recently shown at the 12 Bienal de Cuenca, the 19th Biennale of Sydney and Art in General in New York. Ringborg's work inherently challenges the privilege of language and expression and through this explores notions of originality and individuality in authorship, the role of the artist and the creative act. In deliberately constraining her own self-expression, Ringborg exposes the fine line between chance and free will, and the act of creating without making anything.

Nora Razian: I want to trace a trajectory through some of your works up to your most recent work A World of Blind Chance (2014) and your ongoing The Library of Unborrowed Books (2012).

In A World of Blind Chance, we watch a play in three acts unfurl, with a central male character alone on a sparsely decorated stage, with an off-screen voice, narrating the scene and simultaneously commanding the actor. Both the actor's script and the director's narration/instruction are composed of 'exemplifying' sentences from the Oxford English Dictionary; those sentences that serve to give an example of the different ways a word is used.

I see A World of Blind Chance as a kind of accumulation of your concern with the notion of the individual and individuality, the creative act and the tension between chance and free will. The piece follows on from the works you showed at your exhibition The Apparent Author at Galeri NON in Istanbul in September 2013. The works on display included two text-based works, On Writing (2013) and A Work of Fiction (2013), and two video works, Eternity and Infinity (2013), among other pieces. These were all concerned with the act of creation, the act of authoring, and with the idea of originality. Specifically, in A Work of Fiction you are concerned with the act of writing under the constraint of using only exemplifying sentences from the Oxford English Dictionary, exploring, as you say, 'the act of creating without making anything' and the idea of originality.

This is further developed in A World of Blind Chance, which to me expands on a kind of existential strain that runs through your work. The first act of the play sees the author ruminating on individuality, on being an actor. The second act introduces tensions between the act of creation, and the knowledge of the confines of codes and power structures that we exist within, and the constraints of language – the essence of self-expression. It observes how, within these codes and constraints, there is no inherently original act. Here, the actor touches on the idea of madness and depression, hinting at this 'boundary' state as perhaps the place where free will may exist but it is a state that comes at a price.

In the final act, we see the actor ruminating on chance, fate and free will, and the idea that you build your own future, that you have control, is brought into question.

How does A World of Blind Chance relate to your previous works, and specifically to A Work of Fiction?

Meriç Algün Ringborg: In my previous works, I have been concerned with subjects such as identity and belonging, the bureaucracy of moving across borders, the precariousness of being recorded, the gap between fiction and reality and so forth. A thread that runs through all these subject matters can be formed within questions of language and expression. To express oneself is a very powerful and privileged thing; one that should not be taken for granted. I wanted to create a situation where I was constrained to a limited material and could experiment with expression within these self-imposed limits. I chose the Oxford English Dictionary (and thesaurus), sources I often go to in my everyday life as my reference material, and began to compose texts by only copy-pasting the exemplifying sentences – that is to say the sentences that illustrate how a word is used. On the one hand, this rule I set out for myself was quite limiting, and on the other, it felt strangely liberating. I can't really explain why, but I think it might be due to giving up on the idea of originality from the get-go. Anyway, as it started as an experiment with short paragraphs here and there, it quickly turned into an obsessive act and I ended up with a body of work titled A Work of Fiction. This consists of a short detective/romance novel, and a sound piece titled Metatext (2013), which is a narration of an author's journey into writing and an environment containing objects that belong to an imagined author's space. I recently finished A World of Blind Chance, a theatrical performance of which the script is composed with the same method. So all these works are interrelated under the umbrella of constrained writing, authorship and expression.

NR: Can you talk about the relationship of the off-screen voice to the actor?

MAR: The off-screen voice is the author/director character that both narrates the situation but also commands the actor in what to do and how to do it. I see this dictating and authoritarian side of the narrator as a force that creates a tension between all parties involved. In this version of the performance I worked with Michael Nyqvist, who has been a stage actor at the Royal Dramatic Theatre for a long time, but he wasn't allowed to rehearse the script beforehand. So the half-hour video is basically edited from his first few takes, where he is reading from the script and trying to get a grasp of it whilst acting it out the way the off-screen voice narrates. The struggle that he is going through, trying to understand this rather nonsensical ramble and make the lines into his own whilst performing put him in quite a vulnerable position. And I was, in a way, after that vulnerability as I wanted equally to explore what happened in between the lines, and if within these in-betweens there was the expression of the self, the individualistic traits of that person. But of course, the play can be rehearsed and performed too and that would bring another layer of the script into life. I haven't had the opportunity to do this yet.

NR: Do you feel that this work addresses more existential questions to do with our understanding of how we can act in the world?

MAR: I don't know exactly if this answers your question, but as the title A World of Blind Chance suggests, the work reflects the randomness of our reality and with its methodology of being composed from sample sentences, it emphasizes the complicated relationship between chance and free will. The actor says: 'Man is a rational being. Any man must at some point question whether it is chance or fate that brings things to pass. Man is a master of his own destiny. From the beginning he has been in control of his own destiny.' But are we in fact masters of our own destinies? Or have we created societies where only the privileged get to be the master of their own destinies? And maybe the artist falls in-between.

NR: In the second act of the play, the actor references madness and depression, where he begins to doubt his own sanity, and fails to explain himself. How do you see the absurd, or the realm of the nonsensical (the mad) in relation to language, expression and authorship in your work?

MAR: As I mentioned earlier, this project started as an experiment and quickly turned into an obsession. I guess in this second act of the play there is a certain self-referential side when he talks about the idea of wanting to know everything and trying to achieve this by reading all the books he could lay his hands on but there are gazillions of books that he cannot possibly read in a life time. And then he finds this one book, which I see as a metaphor for the dictionary – but I am assuming this could also be perceived as a holy book which is interesting, too, as in a tension between knowledge and belief – that contains all the answers to all the questions that he is after. But soon after, the book drives him mad as it is constantly changing and evolving. He comes to a point of realization that language is always changing and it is impossible to find one truth. There are many truths and his truth is only one of them.

NR: This slipperiness of language that we experience in your work is explored in another way in your previous works, where we see the way the bureaucratic engines of the state use language as a way to trap and force individual identity. There is something absurd in this that you explore in your work.

MAR: As you say, the absurdities in the language of administration and bureaucracy is something I explored in some of my previous works. In 2009 I made a work titled The Concise Book of Visa Application Forms which is an encyclopaedia-like book consisting of all the visa application forms for all the countries in the world. It is perhaps a parody of the rather ridiculous processes people have invented to control borders. Whilst many of the questions asked in these forms are similar to each other and rather predictable, there are also ones that are very invasive and antagonistic, and there are ones that just don't make sense such as 'Do you want to live temporarily or permanently?' In 2012, I was invited to a show that took over a bunch of billboards throughout two cities, so I used this forum to publicize some of these questions by taking them out of their original context, singling them out and blowing them out of their usual proportion.

NR: This way of focusing in on things and, as you put it, blowing them out of proportion to draw attention to the poetics, absurdity and slipperiness of language and of our systems of organization and categorization seem to me to be a thread in all your work.

Your interest in the marginal or the overlooked also comes out in your ongoing work The Library of Unborrowed Books originally produced in Sweden with the Stockholm Public Library and iterations of which you have so far shown in the Gennadius Library in Athens, 12 Bienal de Cuenca, 19th Biennale of Sydney and Art in General in New York. The work consists of displaying sometimes hundreds of un-borrowed books from a local library, speaking to the idea of disregarded knowledge, or wasted ideas, and is the physical manifestation of this. To me this work speaks of the vast expanse of uncelebrated human production, and of the very real possibility of the creative act fading into oblivion; to the loneliness and futility that haunts every creative act. Does this notion of the futile come into your other works?

MAR: I certainly think so. The whole project of writing from the sample sentences in the dictionary is futile if one chooses to look at it that way. Or writing books that no one ever reads (although you cannot possibly predict that beforehand.) I try to work towards making seemingly useful things; things that could exist within already existing structures, or things that are modelled after what's already out there. I don't make things from scratch so to speak. But the works fail to actually fulfil any utilitarian purpose. Its 'usefulness' lies elsewhere. Questions of futility and usefulness are part of the complications of living and working as an artist as well. Of course, there are points where I question myself like: 'What am I doing? Why am I doing all these projects? Couldn't I contribute to society in a more useful way?' But more and more I've realized that this is the way I am programmed to think. This is what I was taught by my family, in school and so on. So instead I've come to believe that that the world would be a terrible place if everything were measured according to its face value.

NR: When we spoke you explained that you were now thinking of these numerous iterations of the library as a work in itself. Can you say more about this?

MAR: For a long time The Library of Unborrowed Books was just a scribble in my notebook. Then it came to life in 2012 thanks to Emily Ringborg, my librarian sister-in-law, who works at Stadsbiblioteket in Stockholm. When I mentioned this idea to her she said, 'I can make that happen' and she really did make it happen and I am grateful for that. After I made the first version, I started getting invitations to make other ones and, as you mentioned, now there have been five iterations of The Library of Unborrowed Books. I am starting to see it as one work that just happens to take place over a long period of time within different cities, contexts, and libraries.

See Meriç Algün Ringborg's special presentation of her project, Billboards, presented in Ibraaz's online project space, here. From now until January 2015, Ringborg's billboards will be appearing in Ibraaz's banner section on rotation.

Meriç Algün Ringborg is a Turkish artist currently living and working in Stockholm, Sweden. She received her BA in Visual Arts and Visual Communication Design from Sabanci University, Istanbul (2007) and her MFA from Royal Institute of Art, Stockholm (2012). In her work, she employs a variety of media including printed matter, photography, sound and installation; mainly focusing on the themes of nationality, borders, translation, bureaucracy and home. Recent solo exhibitions include: Metatext, Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver (2013); The Apparent Author, Galeri NON, Istanbul (2013); A Work of Fiction, Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm (2013); The Library of Unborrowed Books, Art in General, NYC and A Hook or a Tail, Frutta Gallery, Rome (2013).