Interviews

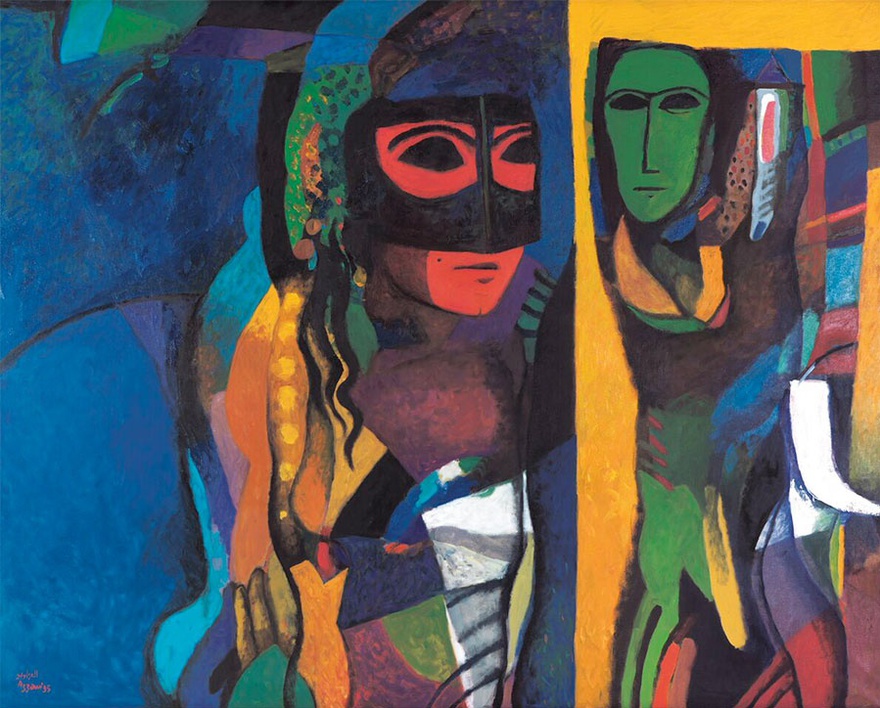

Epic Painting

Dia Azzawi in conversation with Sheyma Buali

Dia Azzawi has painted through decades of political turmoil, painting in and about his native Iraq and across the Arab world. From his first engagement in demonstrations in support of Gamal Abdul Nasser's nationalization of the Suez Canal, through coups, massacres and occupation, Azzawi has reflected ideas on nationalism, isolation and the humanity of the arts in everyday life. His motifs ricocheting from Mesopotamian iconography to the rules of Western Modernism have made him universally appreciated. A prolific artist, he has reflected on many chapters of the world's tumult through visual arts, poetry and sculpture. In this interview, Sheyma Buali speaks to him about the effect of politics he witnessed on the content and style of his work.

Sheyma Buali: One of your first involvements with political action was marching for the nationalization of the Suez Canal in 1956. How did this inform your political outlook, both personally and artistically?

Dia Azzawi: I was in secondary school at the time. I used to go to our school studio and work under the supervision of my teacher, Ibrahim. It was more like a hobby. In 1956 Gamal Abdul Nasser made his decision about the Suez Canal. I attended protests in support of this and I got expelled for joining of a group of students throwing stones at the officers. The school told us to go somewhere else, they couldn't have us. But some days later, King Faisal, who at the time was attempting to improve his own image, decided to visit some schools. One of them was my school. It was known that King Faisal was a painter. I believe it must have been Ibrahim, my art teacher, who convinced to let me back in the school for this occasion, and they did. I went back, and the King came to the studio where I was along with two other classmates. He went around, chatted a bit with people and he left. A month later the school received a letter from the Royal Court saying that the King liked a certain painting very much, and it was mine, it was called 'The Arab Sheikh'. So the school gave it to him as a gift. They also arranged for me to meet him at his palace. I went with the dean, who was still upset about the protest incident. The King's palace was very modest with modest furniture, he was a simple man. He promised me that when I finished school he would send me over to Italy to study art. Of course I thought that was fantastic. But it never happened because three months later there was a coup and he was killed. That was the last I saw him.

Sh.B: So you went from being expelled for throwing rocks at police in protest to being offered a full scholarship by the King. Did this influence you in the long run?

DA: Not much. After secondary school I went to college to study archeology. At that time, I considered archeology as a form of art. The college had a studio run by the pioneer artist Hafedh Al-Droubi. I regularly visited him to work in the studio. A year later I decided to study fine art in Baghdad. For the next five years, I was studying archeology in the morning and art in the evening.

Sh.B: Your use of legends and folklore is like a window into the way you express contemporary life. Could you explain how that works for you?

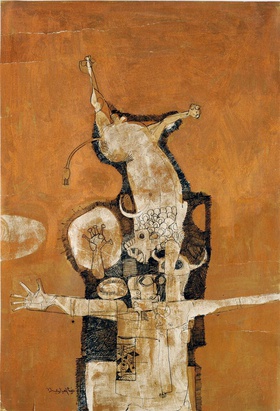

DA: Yes, archeology and the study of Sumerians and Assyrians had a major effect on my artwork. They lead me to looking at ideas on 'identity', which, in Iraq, was a big theme within art movements. In general, a lot of artists do work related to their history. For me, it became very much about history because I was dealing with this every morning. I tried to go deeper into history and identity by investigating these ideas in fairytales and stories. Some of these were very well known myths, the stories of Hussein and Karbala, even though I did not take them from a religious stance. These stories fascinated me. For example, a lot of works for my first exhibition were drawings from the epic of Gilgamesh. And then I got more involved in doing work about Al Hussein.

Sh.B: That is interesting because colloquially, of course you see a lot of paintings of Al Hussein miniature models of Karbala, especially during the month of Ashura.

DA: Yes, but now this has all become very sectarian.

Sh.B: Yes, but this also may have to do with identity, religion or other ideas. What was is about these stories that you wanted to communicate?

DA: I try to create interpretations of these stories. When you come to Hussein, to us he was someone who fights injustice. If you stay within the folkloric meaning it remains limited, too local. In the early 1980's I watched this Pakistani film called The Blood of Hussain. I saw it in a cinema not far from the University of London – I was very excited about this. The film opens with a wide landscape. A white horse jumps into the scene and off the land. The story is about a very poor farmer who tries to maintain his living with his family. He gets some pressure from the corrupt village police. He tries to get help from the Mayor but instead he gets killed. In this aspect you can see Al Hussein, Yazid was the mayor. This was an interesting way of reinterpreting this historical myth into something more contemporary. Strangely, two weeks after the release of this film, Mohammed Ziya' Al Haq came to power.

Sh.B: And Gilgamesh, what is your thread between this epic myth and contemporary humanity?

DA: Gilgamesh goes back 3,000 years. But when you talk about the human aspect of Gilgamesh, you have a character, a hero, whose conflict is death: he does not want to die. Fear of death is at the core of Gilgamesh. He tries his best to get anything that can last forever, which he cannot. This is a fact of life. You can find at least 30 pieces of music about or inspired by the story, by international composers – not necessarily Arabs. There is an opera called Gilgamesh. It may not be a very well-known opera, but it is there. These kinds of stories will forever create new stories.

Sh.B: There are a number of political events that have very much outlined the trajectory of your work. First there was the 1963 Ba'th coup in Iraq. Second is the Six Day War of 1967.

DA: Yes, in the 1960's the Ba'th party came to power. Before that, there were a lot of clashes between them and the communists and other parties. So when they came to power they had already executed and imprisoned a lot of people, for some it was just because of their name. I went to prison for two months for no reason. I lost trust in the political system in Iraq. I was not a party member nor was I involved politically in the way that would put me in prison for two months. After that, what happened in 1967 was that Israel managed to destroy two or three countries in six days. This showed how hollow the whole system was, everything started to collapse: Jamal Abdul Nasser, the entire dream, it all started to fall apart. All the young people who believed he was the hero, they became disillusioned. People started to question the systems, questioning themselves, what they were doing. You either go down the path of a philosopher, were you ask questions for which you got no answers, or you become a politician and go to prison. Or maybe you join a party, which gives you the illusion that you can change the system. Tolerance is low among the Arab countries where you had very powerful regimes. So problems persist between the rulers and the people in these countries. When it comes to aspects of life having to do with oppression and freedom, no intellectual will want to simply stand aside.

Sh.B: These thoughts, decisions, and events have a prominent place in your work. Can you tell us how all of this affected you and your work?

DA: After 1967, I became more related to the Palestinian cause. Many of my friends left Iraq and went to work with the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) in Lebanon. Many decided to either be a fighter, or join a paper as a writer. Either that or you stay in Baghdad and do nothing. But maybe this was the failure of my generation. I kept in contact with my Iraqi friends, as well as the Palestinians in Lebanon. I started to make drawings and graphics to publish in a Palestinian magazine called Al Hadaf (the objective.) From then on I used the Palestinian issue to express my attitude in politics. I did work about Black September, the Tal El Zaatar massacre, the camps destroyed by the Syrians and Phalangists. My friend, Ghassan Kanafani, was the first intellectual to be assassinated by the Israelis. I felt very strongly that things were going wrong, there there was injustice, and I was trying to express these feelings. Maybe in a way this was me thinking of Iraq, the country I had left 35 years ago without returning to. I started to ask myself, why don't I have a country? I had these feelings, and I could understand the Palestinians because they have no country. They have land and access to people, but they do not have their own country. So politics taught me to work indirectly way in order to give each piece a longer life.

Sh.B: Can you tell me about a work that you did that strongly reflected your political experience?

DA: A painting that I did in 1983 was entitled Sabra and Shatila. I had exhibited this painting in Kuwait and they asked me if they could keep it in their museum for five years as a lone. I agreed to that. And luckily, after five years I remembered to contact them to get my painting back. Two weeks later, Saddam invaded Kuwait. The entire area where my painting was stored was bombed. I was so lucky I had gotten my painting out when I did. These are the ironies of my life. If I had delayed by one month, that painting would be gone, no longer there.

Sh.B: Besides the modernist and impressionist painting and sculpture, you also created graphics and poster design, which were surely political in their essence. What do you think was a lasting legacy in the politics of the late 50s and 60s?

DA: Posters are something that I liked for a long time. They are fantastic for culture, art and even politics. For a short time in Iraq in the 1970s we have a good posters movement. But unfortunately that died when the government took over and started to use the posters in their own terms.

Sh.B: I know that you have drawn and painted some very special, limited – and in some cases unique – edition books for poetry and literature. Can you tell me about these books?

DA: These are like object art. For example, I chose an excerpt from Abdelrahman Munif's Cities of Salt and made limited edition books. I hand-make the pages based on the text and I worked with the sleeve. These are not common among Arab artists, except those who live in Europe. Another one I made one with the Syrian writer Halim Barakat, who lives in Washington. Together we decided on the text and I created the images, we made them in English and Arabic. I silk screened only 12 copies of this text.I made a book with Bahraini poet, Qassem Haddad, for his rendition of Majnun wa Laila. These are all in the exhibition. I did work with a very small poem by a French poet which was translated into 5 or 6 languages. I sent it to a friend who translated it into Arabic first. It is about a bird. I later found out that there are thousands of renditions of this poem. With books, it is unfortunate that the Arab world do not make long lasting ones that stand as documentation of our literary cultures.